Coming Clean: New Postcolonial Light on Dutch East Indies Literature

Fifty years after Rob Nieuwenhuys’s standard work the Oost-Indische Spiegel (Mirror of the Indies), two new important books on Dutch East Indies literature have been published. De postkoloniale spiegel (Postcolonial Mirror) is a scholarly overview, De nieuwe koloniale leeslijst (New Colonial Reading List) contains more journalistic work. Both editions aim at a complete revision of the existing image: no more nostalgia or white innocence, but an exposure of the unequal power relations in colonial society. For the first time, writers from Indonesia themselves are also given attention. Dutch scholar Reinier Salverda compares the two books, situates them in a broad literary and historical context and makes critical comments.

In 1972, Rob Nieuwenhuys, the doyen of Dutch East Indies Literature, published the Oost-Indische Spiegel (Mirror of the Indies), his history of “what Dutch writers and poets have written about Indonesia, from the early years of the VOC until today”, written with great knowledge and clarity of composition, eminently readable, presented with taste, style and outspoken literary judgement. Of this still unsurpassed standard work, an Indonesian adaptation, Bianglala Sastra, was published in 1979 by Dick Hartoko; followed by a condensed American version in 1982 by Frans van Rosevelt, Mirror of the Indies, A History of Dutch Colonial Literature, which was published by E.M. Beekman at the University of Massachusetts University Press in Amherst, where Beekman was professor of Dutch.

In 1996, Beekman published his own magnum opus, Troubled Pleasures. Dutch colonial literature from the East Indies, 1600-1950, focusing on the twenty most significant writers of this literature and the remarkable imagination and striking literary qualities of their works. Then in 1998, we find Alfred Birney’s history and anthology of Dutch East Indies literature since 1595: Oost-Indische inkt, 400 jaar Indië in de Nederlandse letteren (East Indian Ink, 400 years of the Indies in Dutch literature), in around fifty gripping Dutch stories, including 35 from after 1945. In 2002, Theo d’Haen, Professor of Comparative literature (Leiden & Louvain), gave Dutch East Indies literature its rightful place in his vast survey of the many kinds of literature of the colonial empires of Europe, in the two volumes in Dutch of his Europa Buitengaats (Europe Overseas). This was followed in English in 2008 by A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures: Continental Europe and its Empires (ed. by Prem Poddar et al). Also in English, between 1981 and 1988, Beekman published his invaluable twelve-volume Library of the Indies.

Taken together: a solid harvest of some six thousand pages on Dutch East Indies literature, inspired by Rob Nieuwenhuys, who also founded the Leiden literary journal, Indische Letteren, a thriving platform from 1986 till today for the study of this unique subdomain of Dutch colonial literature.

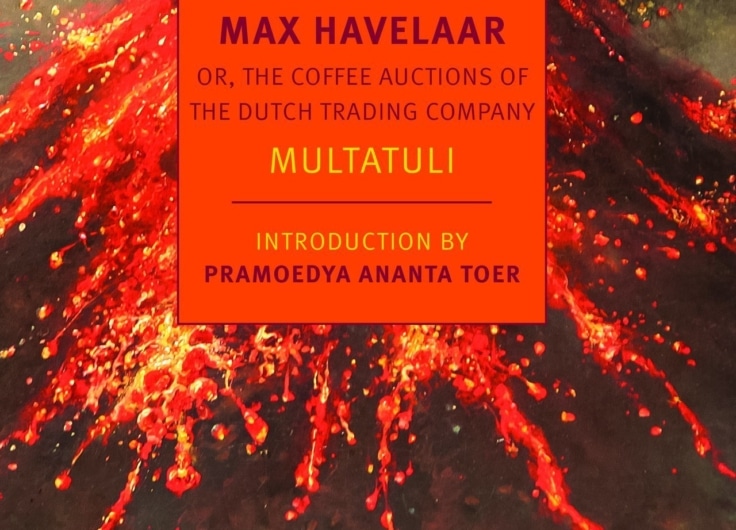

Postcolonial – ever since Multatuli

Today, fifty years after Nieuwenhuys, we have the new Postkoloniale spiegel (Postcolonial Mirror), edited by Rick Honings et al, beautifully presented and illustrated, available both in print and online open access. Its twenty-six chapters were written by an international group of literary scholars, including three from the University of Indonesia in Jakarta-Depok. Shortly before, there was the more journalistic volume De nieuwe koloniale leeslijst (New Colonial Reading List), edited by Rasit Elibol, half of its twenty-four chapters dedicated to Dutch East Indies literature. Both volumes take their starting point from the great nineteenth-century writer Multatuli (1820-1887) and his magnum opus, Max Havelaar (1860; most recently translated into English in 2019 as a New York Review of Books Classics Original). Flowing from Multatuli until the present, they cover a wide range of Dutch East Indies writers – in the Reading list until Helga Ruebsamen’s The Song and the Truth

(2000); in the Mirror until Dido Michielsen’s Lighter than me (Lichter dan ik, 2019; English theatre performance in 2022).

In the Postcolonial Mirror, the central theme is the long-running debate about the social position and identity of the mixed-race Indo-Europeans (Eurasians, Indo’s) in the former Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia), between its three main demographies: the colonial upper class of the Europeans; then the large mass of the Indonesian Natives (Javanese, Balinese, Acehnese, Batak, Moluccans, Sundanese, Macassarese, Buginese and very many others), and thirdly, the Foreign Asians, such as the Chinese, Arabs, Indians and others (though not the Japanese, who always counted as Europeans). While in Nieuwenhuys’s massive survey, we can find a lot already on the completely different world, culture and society of that former colonial empire, note that this was not his primary focus: what interested him above all was the literary qualities of those many Indies texts he discussed in their historical and sociocultural context.

The primary focus of the 'Postcolonial Mirror' is not on texts and literature, but instead on the ideas and ideology behind them

Here, the Postcolonial Mirror takes a different view: “What we did not have until now is a survey of Dutch East Indies literature from Multatuli till today written from a postcolonial perspective, which through critical discourse analysis focuses on the unmasking of inequalities of power structures and othering strategies”. The primary focus here is not on texts and literature, but instead on the ideas and ideology behind them; on the tacit assumptions between the lines, the prejudices emanating from them; and the mentality, the discourse, the everyday racism, the all too common sexism, repression, violence and discrimination, which were the key characteristics of colonial society. Many very different factors were involved here: social status, race, money, sex, origin, descent, culture, language, morals, skin colour, religion, etcetera.

Likewise, the Postcolonial Mirror aims to conduct “a self-critical investigation into how literature deals with the colonial past”. “Postcolonial”, here to be taken as a critical rereading of Dutch novels from the colonial era, but this new Mirror also engages explicitly with thirteen novels that were published after, and outside, the colonial domain covered by Nieuwenhuys. The rereading practised here brings to bear a conceptual framework with an arsenal of critical approaches covering the broad field of postcolonial discourse studies, ranging from Orientalism, Representation and Othering, via Stereotyping, Racism, Sexism and Marginalisation, all the way to Decoloniality, Queer Theory and Intersectionality. “Critical” here means “Ideology-critical”, as developed by leading international postcolonial thinkers and theoreticians such as Edward Said, Gayatri Spivak, Robert Young, Mary Louise Pratt, Ann Laura Stoler, Gloria Wekker and Elleke Boehmer – the last two of whom each contributed a chapter to the Postcolonial Mirror.

The views we have of colonial history are no longer the nostalgic myth of tempo doeloe, nor the white innocence of the humane coloniser, nor his good works and self-justifications in the former Dutch East Indies

It is this postcolonial debate that takes centre stage here. The result is a comprehensive revision of the views we have of colonial history: no longer the nostalgic myth of tempo doeloe, nor the white innocence of the humane coloniser, nor his good works and self-justifications in the former Dutch East Indies. As Rasit Elibol says, in his preface to the New Colonial Reading List: “Time now to revise the traditional canon, so that really everyone will be able to recognise themselves in those tales”.

Indies

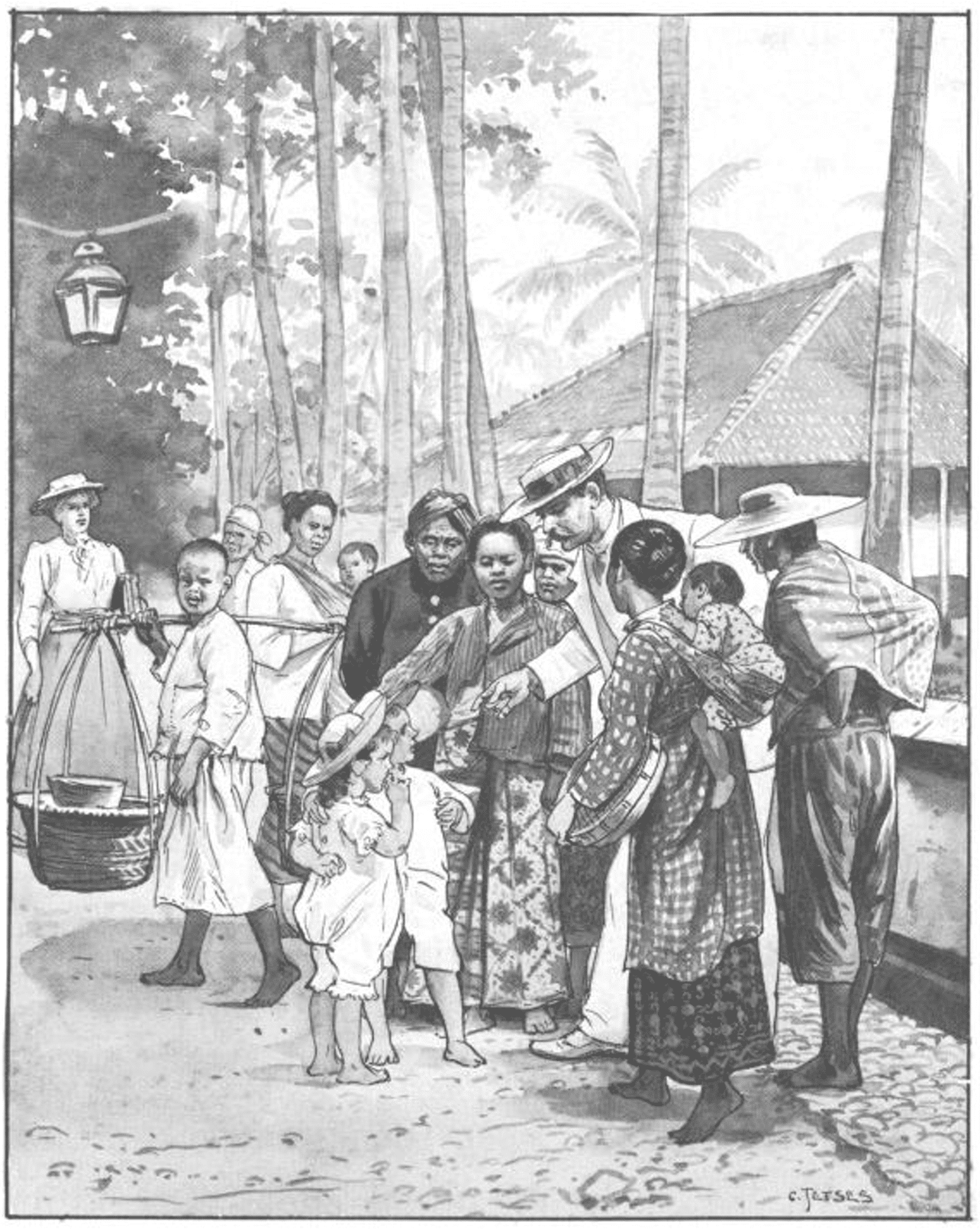

The postcolonial perspectives developed in the various essays in the two volumes have much to offer. A prime example in the Postcolonial Mirror is the chapter by Amalia Astari (Cologne & Jakarta) and Rick Honings (Leiden) about the children’s book, Ot and Sien in the Dutch East Indies (1911), written for Dutch school children and then adapted for the colonies by Jan Ligthart and H. Scheepstra. The analysis by Astari and Honings reveals that what appears to be an innocuous book of Dutch texts and pictures for children, on closer inspection turns out to be a thoroughly colonialist book, with Indies-adapted texts and illustrations, written from a western sense of superiority and an ideology of unequal power relations, which presents Dutch supremacy over native subordinates as totally natural and self-evident. Growing up with a text like this, children in the colonies were being spoon-fed the white colonial discourse, including its stereotypes and prejudices, which at the time were dominating Dutch East Indies society.

Ilustration from the children's book 'Ot and Sien in the Dutch East Indies' (1911). A thoroughly colonialist boook, with Indies-adapted texts and illustrations, written from a western sense of superiority and an ideology of unequal power relations.

Ilustration from the children's book 'Ot and Sien in the Dutch East Indies' (1911). A thoroughly colonialist boook, with Indies-adapted texts and illustrations, written from a western sense of superiority and an ideology of unequal power relations.Equally revealing is the chapter by Elleke Boehmer (Oxford) and Coen van ‘t Veer (Leiden) about The Hidden Force (1900) by Louis Couperus (1863-1923). In their analysis, from a queer-theoretical perspective, they highlight the forbidden desires and repressed fears of the ambivalent colonialist Couperus was, and the ensuing tension in his novel between on the one hand the Dutch colonial elite with its decadence, adultery and suchlike goings-on and, on the other, the mystic forces of the East, the Javanese black magic and its hailstones raining down, and the white hadji representing the unfathomable Islamic threat underneath the narrative.

Their analysis in a way reconfirms the 1918 colonial assessment of Couperus by the Government Committee for Popular Reading in the capital Batavia (today Jakarta). In their Guidelines for the popular libraries of the archipelago they singled out Couperus, decreeing that there should be no place for “works… which subvert good morals and common decency …. which cannot be read by each and every member of a household, such as e.g. Couperus’s works The book of small souls…. and also so-called psychological novels, such as many works by Couperus; and…. all works that emanate an anti-Dutch spirit”.

Madelon Székely-Lulofs has been appraised as a female Multatuli. Her colonial novels presented a shocking picture of the violence in the Dutch plantations in North Sumatra.

Madelon Székely-Lulofs has been appraised as a female Multatuli. Her colonial novels presented a shocking picture of the violence in the Dutch plantations in North Sumatra.© KITLV

Such Dutch colonial values and judgments were unquestioned at the time. We see this too in the Postcolonial Mirror’s chapter on Madelon Székely-Lulofs (1899-1958) by the Hungarian scholar of Dutch Literature, Gabor Pusztai (Debrecen, Hungary). The succès de scandale of her colonial novels Rubber (1931) and Coolie

(1932) and the shocking picture these presented of the violence in the Dutch plantations in North Sumatra, caused an outcry against her, especially when the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in Geneva censured the Netherlands over the slavery conditions it practised in its colonies. On account of this, she has been appraised as a female Multatuli.

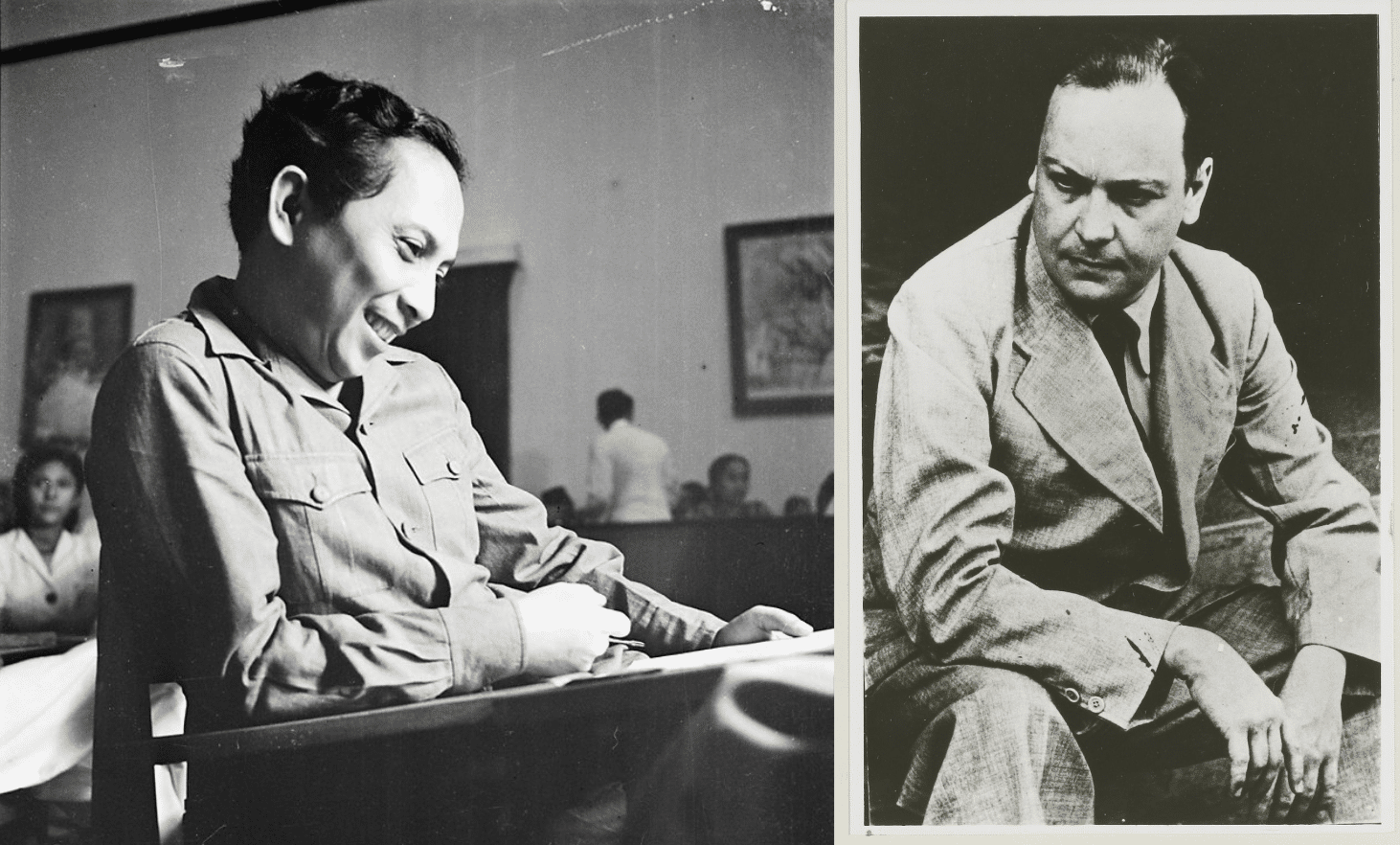

Or take Edy Du Perron (1899-1940), the famous author of his Country of Origin (1935), which in both volumes under discussion here is analysed from a decolonial and intersectional viewpoint by Gloria Wekker (Utrecht University), as an autobiographical document, full of the colonial racism, sexism, violence and homophobia of its central character, Arthur Ducroo. All true, but Ducroo is not Du Perron; and Wekker pays little attention to the difference: to the dialogic construction of Du Perron’s novel in which André Malraux, under the name of Heverlé, is one of the central figures; to Du Perron’s personal journey of conscience and his critical reckoning with the colonial values he grew up with, and then stepped away from; and to his political decision in 1939 to leave the Dutch East Indies to go to the Netherlands and join the fight there against fascism and the growing threat of Nazi Germany.

In this respect, we note too what Sutan Sjahrir (1909-1966), the leading Indonesian social-democrat thinker and first prime minister of the Indonesian Republic after Independence, wrote in 1947 about Du Perron in the Dutch language literary and cultural magazine Oriëntatie

in Batavia:

What the author Du Perron before the war has done in crosscultural contact and thus won in sympathy for the Netherlands, would be hard to overestimate. His influence on a number of young Indonesian intellectuals was immense, through the way in which he made contact with them; and this influence, through his writings, continues to grow, also among those who have not met him in person. Du Perron has succeeded in winning a trust amongst Indonesians which they have never given to other well-meaning Dutchmen. Sympathy for Dutch culture is a characteristic of this group of intellectuals, who went on to play a leading role in the Indonesian Republic; they acquired this under the influence of Du Perron. He approached the Indonesians not as an interesting outside study object, like many ‘ethical’ Dutchmen did. No, he met them as equals, as humans, recognising their common humanity.

Sjahrir, the leading Indonesian social-democrat thinker and first prime minister of the Indonesian Republic after Independence, wrote of author Eddy du Perron that he did not approach Indonesians as an outside study object, but met them as equals.

Sjahrir, the leading Indonesian social-democrat thinker and first prime minister of the Indonesian Republic after Independence, wrote of author Eddy du Perron that he did not approach Indonesians as an outside study object, but met them as equals.© Cas Oorthuys / Nederlands Fotomuseum / KITLV

Indo or Indisch?

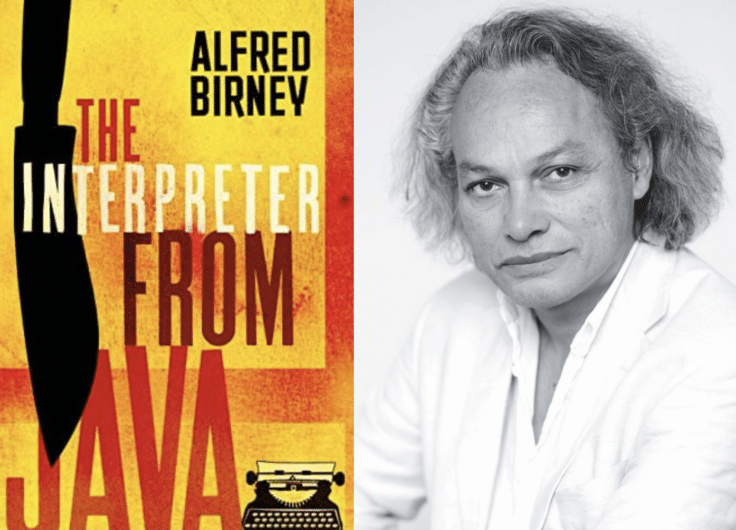

In his chapter in the Postcolonial Mirror

on the Indo writer Alfred Birney and the hard-hitting memories of the Indonesian war of Independence in his bestselling The interpreter from Java (2020), Jaap Grave (Amsterdam Free University) points out how over the years there have been semantic shifts and confusions in and around common terms like Indisch

(i.e. anything or anyone coming from the Dutch East Indies) and Indo (i.e. mixed race, Eurasian from the archipelago). Neither of these two terms had legal status such as, for example, ‘Europeans’, ‘Natives’ and ‘Foreign Asians’, the three legal categories defined in the Colonial constitution. Indo

and Indisch cut across these legal and administrative distinctions, as everyday social and ethnic labels were in common use throughout the multilingual and multiracial apartheid society which then was the Dutch East Indies. Indo’s

could thus be found everywhere, as second-class members in all three legal categories.

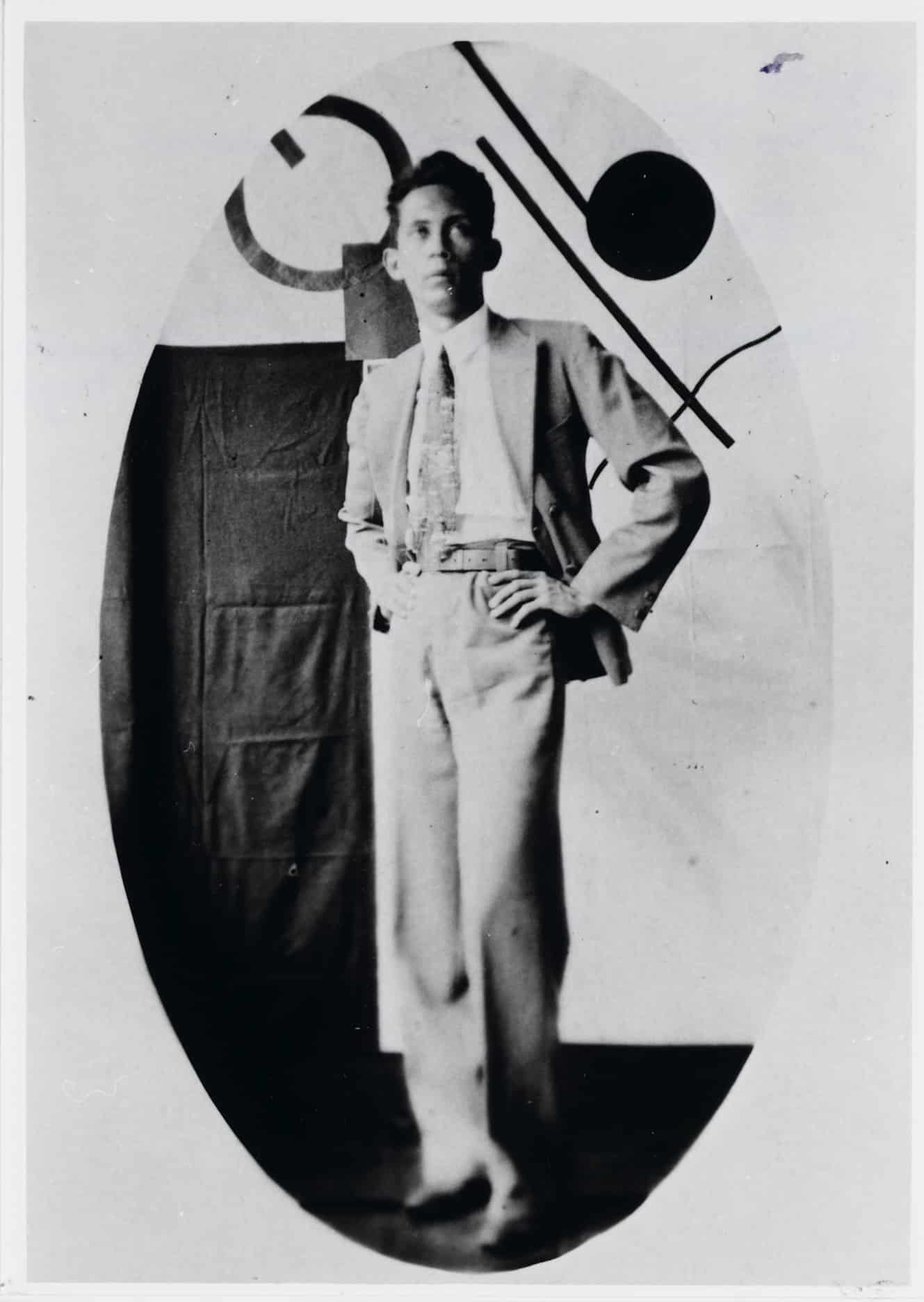

It was Tjalie Robinson (1911-1974) – himself an Indo, like his alter ego, Vincent Mahieu – who, after the war, pioneered Indo writing in Dutch literature, first in Jakarta, then later also in the Netherlands. This is the subject of the inspirational chapter on Robinson/Mahieu, “Looking for an Indo-Identity of one’s own”, by Jeroen Dewulf (Berkeley), who sets out how Robinson, in his writing and other activities, explored the space available for Indo’s in their in-between-position, going on from there to develop his fusionist idea of the Creole as the true global man of the future.

Tjalie Robinson pioneered Indo writing in Dutch literature. He explored the space availlable for Indo's in their in-between-position.

Tjalie Robinson pioneered Indo writing in Dutch literature. He explored the space availlable for Indo's in their in-between-position.© KITLV

With this vision, Robinson has inspired the next generations of Indo writers. One of the more prominent of these is Marion Bloem (born Arnhem 1953), laureate of the Constantijn Huygens Prize for Dutch literature 2022, and of the Edy Du Perron Prize 1993. Her work – from her debut novel, No ordinary Indies girl (1983) right through to her recent Indo (2022) – is analysed from a social-critical race and gender perspective by Liesbeth Minnaard (Leiden), who focuses on uneasy processes of identity formation in contemporary Dutch society, where – long before Me Too

– a non-white woman in white Dutch society could be cut down as a “ball buster”.

For good reason, the opening motto of Bloem’s debut novel came from the quatrain “Schizophrenia” by the great Dutch Indies poet in Jakarta, Han Resink (1911-1997), in his ‘Transcultural’ (1981):

When will come the time

the European in me

will kill the Indonesian, or the Javanese

the Hollander, or lower still,

the country bum the Jakartan?

Tjalie Robinson’s vision led to fierce debate in the 1990s about the question who in the Netherlands was entitled to call themselves ‘Indisch’: only Indo’s, or also white people of (post)colonial origin from the Indonesian archipelago? This is still a live issue today, in more than half of the Postcolonial Mirror’s 26 chapters – but not always without confusion: sometimes Indisch is taken to mean Indo, at other moments its total opposite. Least unclear, to me, is to take Indisch not as a synonym (or even a euphemism) for Indo (Eurasian), but as a much wider umbrella term, an inclusive and comprehensive notion covering any and everything stemming from the former Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia); whereas, in addition and alongside Indisch, other, more particular terms of identity are available separately, for Indo’s, Javanese, Chinese, Moluccans and Europeans, for Christians, civil servants, military men, missionaries, even white colonials. And of course, for writers too: every one of them with their own individual, hybrid identity within Dutch East Indies literature.

To me 'Indisch' is a wide umbrella term, an inclusive and comprehensive notion covering any and everything stemming from the former Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia)

Here, however, the editors of the Postcolonial Mirror seem to prefer a literary future on the principle stated by Jacqueline Bel (Amsterdam Free University): “Indisch literature ought to be written by Indisch people”. Here I take a different view: writers, whether they are Indisch or not, are never exclusively tied to that identity. They are free to write what and wherever their pen or mind may lead them; that is what Multatuli teaches us. From this point of view, important literary works like Tine or the Valleys where life goes on (1987, by Nelleke Noordervliet, a biographical novel on Multatuli’s wife Tine) or The Two Hearts of Kwasi Boachi (1997, by Arthur Japin) undoubtedly deserve a place within Dutch East Indies Literature too.

Indonesian dissenting voices

A further remarkable innovation is that in both volumes we get to hear the voices of Indonesian writers. Of particular interest here is chapter 15 of the Postcolonial Mirror, by the late Christina Suprihatin (University of Indonesia, Jakarta-Depok) and Coen van ‘t Veer (Leyden), on the only two Dutch-language novels written by Indonesian women writers: Unharnessed (1940) by the Sundanese Suwarsih Djojopuspito (1912-1977), and Widjawati (1948) by the Javanese Arti Purbani (1902-1998; pseudonym of Partini Djajadiningrat). Both women published their novels first in Dutch in the Netherlands, then later in independent Indonesia.

Next, in the New Colonial Reading List, we find the essay “The fate of the Moluccans” by the Amsterdam journalist Lotfi El Hamidi, about the moving novella ‘Below the snow an Indisch grave” by Frans Lopulalan (1953-2000), the son of a Moluccan soldier of the disbanded Royal Dutch East Indies Army, who remembers the pain and injustice inflicted on his parents when at the time of Indonesian Independence they were shipped over to the Netherlands where they were summarily dismissed en bloc. The fourth Indonesian voice in the Reading list – discussed by the Dutch-Surinamese writer Tessa Leuwsha – is that of the Dutch translation of the Indonesian Buru-tetralogy (1980-1988) by Pramoedya Ananta Toer (1925-2006). Under President Suharto he spent many years as a political prisoner on the island of Buru in the Moluccas – just as Sjahrir had in the 1930s, first in the Dutch Boven-Digoel concentration camp, then in exile on Banda Island. This is how Pramoedya dedicated his work to his friend the poet Han Resink:

Han, indeed this is nothing new.

This narrow path has been trod many a time

already, it’s only that this time the journey

is one to mark the way.

Four Indonesian voices in Dutch. Not much, perhaps, but it is a beginning. It will not be easy to improve upon this, since the first question here is whether there really is something like an Indonesian dissenting voice. The answer is: Yes – and a lot more than we might think or know today. Also: this Indonesian dissenting voice has made itself heard long before, and much longer too, certainly in Dutch. We can start a century ago with the Dutch-language journal, Bintang Hindia (Star of India), published from 1902 to 1907 by Abdoel Rivai; then the world-famous Letters

(1911), in Dutch, by the Indonesian national heroine, Kartini; and the anti-Dutch satirical pamphlet If I were a Dutchman (1913) by Suwardi Suryaningrat, who because of this was banned by the Dutch authorities from his country of origin. But our ignorance is vast: Suryaningrat is mentioned once in the New Colonial Reading List; the Postcolonial Mirror mentions Kartini, but only in passing; and Rivai is nowhere to be found.

The Indonesian dissenting voice made itself heard early on, including in Dutch, for example in Abdoel Rivai's magazine 'Bintang Hindia' (1902-1907).

The Indonesian dissenting voice made itself heard early on, including in Dutch, for example in Abdoel Rivai's magazine 'Bintang Hindia' (1902-1907).© KITLV

Today, meanwhile, we have the freedom-loving texts by Indonesians which have been collected and published by Harry Poeze and Henk Schulte Nordholt in The call for Merdeka (1995, Leiden), with a preface by the leading Dutch East Indies author Hella Haasse (1918-2011). Alongside this, we also have the many personal and critical statements by Indonesians on their experiences under the Dutch, gathered by Hans Beynon in his Forbidden for Dogs and Natives

(1995).

Earlier we noted the cultural impetus from Du Perron and Sjahrir in the thirties and after. Between 1947 and 1954, the Jakarta magazine Oriëntatie, led by Rob Nieuwenhuys, aimed to build bridges between the two cultures by publishing stories and poetry in Dutch by Indonesian writers such as Chairil Anwar, Mochtar Lubis, Joke Moeljono and Pramoedya Ananta Toer. In 1954 this was followed by the Indonesian scholar RB Slametmuljana with his Dutch-language PhD at Louvain university, Poetry in Indonesia, a literary and linguistic study, in which he demonstrated how the revolutionary Indonesian poet Chairil Anwar (1922-1949) had become an expressionist poet under the influence of leading Dutch poets of the thirties, Marsman and Slauerhoff.

Later still, the Indonesian scholar and critic H.B. Jassin (1917-2000) translated the most important work of Dutch literature, Multatuli’s Max Havelaar, into Indonesian; and when in 1973 he received the Dutch Nijhoff translation prize for this, he stated quite clearly: “This literature does not only belong to the Netherlands, but also to Indonesia”.

Translation and reconciliation

From both sides, Indonesians and Dutch people have continued to write and read each other, and cultural contacts between Dutch and Indonesian writers have continued to develop. From both sides, writers, translators, scholars and publishers have contributed much here, with their seductive and nostalgic myths, their memories and remembrances but equally also their critical unmasking of these. It is here that we can find points of contact and connection through literature, which may cast an illuminating sidelight on the course and dynamics of Indonesian-Dutch cultural relations.

Think of the volume of Indonesian poetry, Flower on a rock (1990) by the Indonesian writer Sitor Situmorang (1923-2014) in the Dutch translation by Kees Snoek; and conversely, the Dutch poetry of Remo Campert (1929-2022), translated into Indonesian by Linde Voûte in the bilingual volume Rataplan/Lamento (1999). Today, both sides know less and less of each other’s languages, so we are more and more dependent on translation. This in turn presents new opportunities for critical-comparative research into texts from both cultures in their contexts, colonial as well as postcolonial.

As an example, building on the example of the many stories and novels by Pramoedya Ananta Toer (and so many other works of Indonesian literature), which over the years have been translated into Dutch, we may take a closer look at the Dutch-language anthology, A source which will never fade: Voices of contradiction in poetry and prose from Indonesia (1993, Amnesty International, Amsterdam) by Cara Ella Bouwman, in which Indonesian writers, poets, journalists and ex-political prisoners from the post-1965 period are given a voice of protest about human rights under President Suharto. Going further, we now also have the Indonesian novel Saman (1998) by Ayu Utami, translated into Dutch in 2001 by Maya Sutedja-Liem and Monique Soesman (and in English in 2005) – an innovative literary work which in 2000 was awarded the Prince Claus Prize for Culture and Development, as an outstanding sample of Post-Suharto Indonesian Literature, full of street noise and critical debates on contemporary issues such as freedom, equality and human rights – issues, which in the Indonesian archipelago have been the order of the day ever since Multatuli, where they matter no less than in the Netherlands.

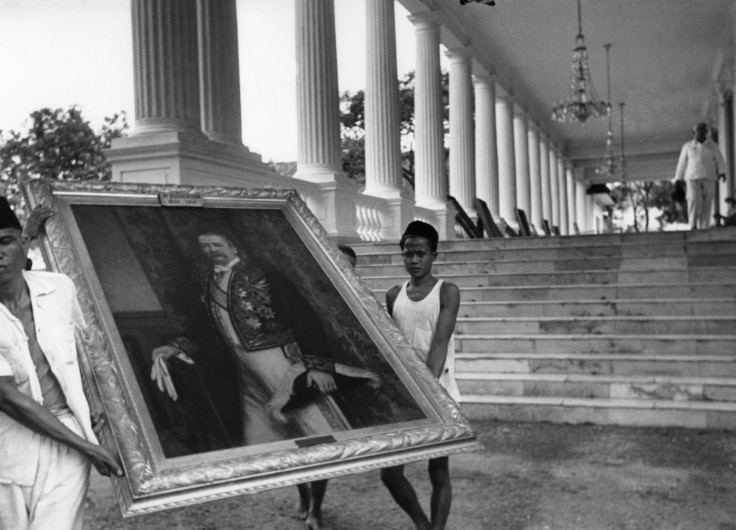

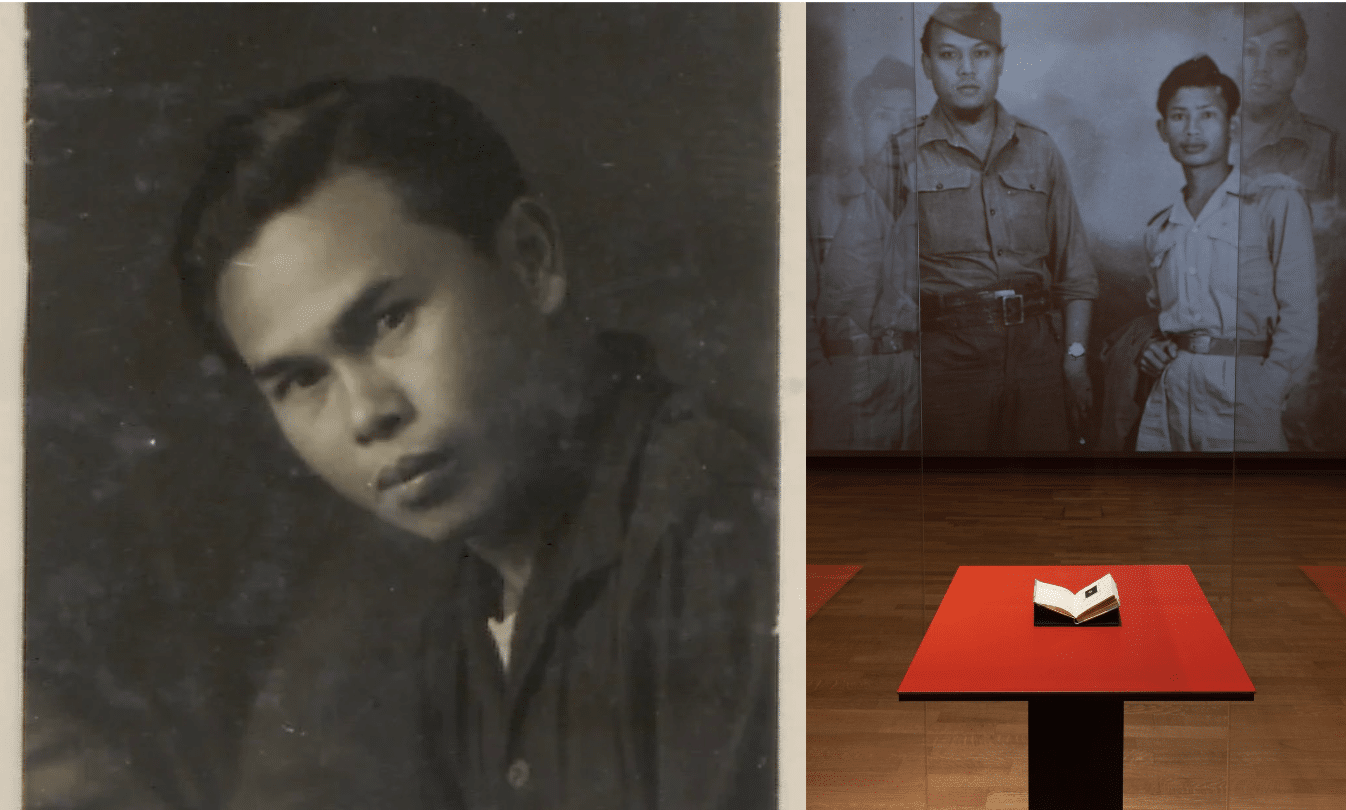

A lot more will need to be done. Think of what Sjahrir asked for: reconciliation and shared humanity, and what literature is capable of contributing here. Take the great exhibition Revolusi! Indonesian Merdeka! in 2022 in the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum, where the opening scene was dedicated to Sutarso Nasruddin, a soldier of the Indonesian elite Siliwangi division, who in 1948 was executed by Dutch troops, and now presented as one of the iconic faces of the Indonesian Revolution. Standing there, larger than life, his effigy originating from a Dutch military archive in the Netherlands, where his personal photo album was kept among the spoils of war. In 2004 this album was sold off to the Royal Institute of Language, Culture and Anthropology in Leiden, and now became a confrontational image in the Rijksmuseum. It could equally have found a place in Thom Hoffmann’s impressive photo album of 2019, A Hidden History, documenting the Indonesian archipelago during the Dutch era, from 25 October 1814 until Indonesian Independence in December 1949. But Nasruddin’s little photo book has not yet been given back as a kenangan

(memento) to his family in Indonesia, and reconciliation has not happened.

Sutarso Nasruddin was a soldier who in 1948 was executed by Dutch troops. His personal photo album was kept in a Dutch military archive and never returned to his family in Indonesia.

Sutarso Nasruddin was a soldier who in 1948 was executed by Dutch troops. His personal photo album was kept in a Dutch military archive and never returned to his family in Indonesia.© KITLV

How differently this could have been done. See for example the Memoirs (1970) of the Indonesian nationalist Margono Djojohadikusumo (1894-1978), a friend of Tjalie Robinson. In his Memoirs, Margono commemorates, in Dutch, his two sons, Subianto (21 years) and Sujono (16 years), both members, like Nasruddin, of the Siliwangi-division. On 25 January 1946, they fell in action in the Indonesian freedom struggle in Serpong (near Tangerang close to Jakarta), and their father honoured them with a fragment of a poem that Subianto carried in his poetry album, written by the Dutch poet and visionary socialist, Henriëtte Roland Holst (1869-1952). Her text, which reads like an ending as much as a beginning, is printed in Margono’s book as a memento, together with its Indonesian translation by his fellow revolutionary, Rosihan Anwar, and also keeps alive the memory of their sacrifice in the Indonesian war cemetery of Tangerang:

We are not the builders of the temple,

We are only the porters of stones,

We are the generation that must perish

So a better one may rise from our graves

Kami bukan pembina tjandi.

Kami hanja pengangkut batu,

Kamilah angkatan jang mesti musnja

Agar mendjelma angkatan baru,

Di atas kuburan kami lebih sempurna

Dynamism and vitality

Bringing together Dutch East Indies literature with the critical postcolonial perspectives developed in those two volumes reveals itself as a productive strategy, generating an enlightening contribution to our critical understanding of the Dutch colonial past in Indonesia. Here too, however small, the inclusion of Indonesian counter voices is a new beginning, and it does make a valuable contribution.

With their incisive studies and discussions, some seventy years after the end of the former Dutch East Indies, both volumes make clear that this literature presents a dynamic domain that is alive and kicking, which continues to fascinate many readers, and promises many further discoveries. Not just in Indonesia and the Netherlands, but also far beyond these two.

References

Rick Honings, Coen van ‘t Veer & Jacqueline Bel (eds.), De postkoloniale spiegel. De Nederlands-Indische letteren herlezen [= The postcolonial mirror. Rereading Dutch East Indies literature], Leiden University Press, 2021, 536 p.

Rasit Elibol (ed.), De nieuwe koloniale leeslijst

[= The New Colonial Reading List], Das mag/De Groene Amsterdammer, Amsterdam, 2021, 238 p.

Margono Djojohadikusumo, Herinneringen uit drie tijdperken – Kenangan tiga zaman – Memories of 3 generations. In English: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1963 [Djakarta, Indonesia, 1969]

Prem Poddar et al. (eds.), A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures: Continental Europe and its Empires. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2008

Reinier Salverda, ‘Nederlandse literatuur in Indonesië, 1945-1995’, In: Neerlandica Extra Muros XXXV, 1 (1997), pp. 1-12

Reinier Salverda, ‘Image and Counter Image of the Colonial Past’, In: Douwe Fokkema & Frans Grijzenhout (eds.), Accounting for the Past, 1650-2000 [= Dutch Culture in a European Perspective, vol. 5], Palgrave/Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2004, pp. 67-92

Reinier Salverda, ‘“For Justice and Humanity” Multatuli and Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Dutch-Indonesian Literary, Historical and Political Connections’, In: Thomas F. Shannon & Johan P. Snapper (eds.), Dutch Literature and Culture in an Age of Transition, Nodus, Münster, 2007, pp. 121-140

Reinier Salverda, ‘Countering the Forgetting: Dutch Indies Literature in the Twenty-First Century’, at: www.the-low-countries.com, 2002

Sjahrir, Wissel op de toekomst. Brieven van de Indonesische nationalist aan zijn Hollandse geliefde [= A promissory note. Letters from the Indonesian nationalist to his Dutch love], bezorgd door Kees Snoek, Van Oorschot, Amsterdam, 2021, 279 p.

Harm Stevens, Revolusi! Indonesia independent. English edition: Rijksmuseum/Atlas Contact, Amsterdam, 2022, 272 p.

Wim Willems, Tjalie Robinson, biografie van een Indo-schrijver [Biography in Dutch]. Bert Bakker, Amsterdam, 2008, 599 p.