Cycling With the Romans Through Greater Belgium: From Boulogne to Tournai

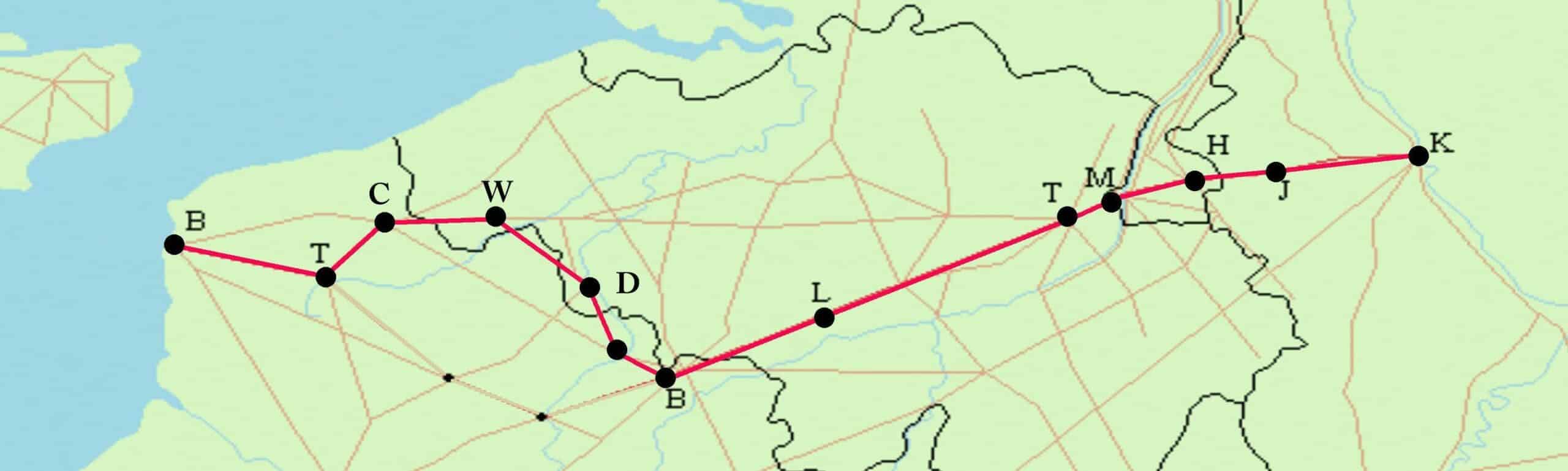

One square on the map, 500 kilometres wide: in 57 BCE Julius Caesar used the North Sea, the Chanel, the Seine, the Ardennes and the Rhine as borders for his newest prize, Gallia Belgica. The united tribes of the Belgae would never again hold so much land. The East-West artery laid by the Romans, the Via Belgica, is still there. Wieland De Hoon explores the ancient Roman road by bicycle. From Boulogne to Cologne in four stages.

Via Belgica

Via BelgicaKm 0 - Boulogne (Gesoriacum)

Our bicycle journey begins on the train. We load our bikes at Lille Flanders. In a wide arc by way of Amiens we reach the grey harbour city Boulogne or Gesoriacum on the Channel coast of France. Our trip will go from West to East: we find the Roman circular border – de limes – a more suitable symbolic endpoint than the Oceanus Brittanicus.

At the coast in Boulogne

At the coast in Boulogne© Saskia Dendooven

The best view out to sea is from the reminiscently-Roman, bronze statue of an eagle on the coastal boulevard. Although the statue is there to honour a bi-plane pilot who died in an accident, one also imagines oneself standing next to the emperors Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula and Claudius. They saw this coast as their springboard to Brittania. Before Claudius’ conquest of Britain in 43 CE, Gesoriacum first had the madman Caligula to contend with.

The chronicler Suetonius described how the emperor, somewhere along the coastline, ordered his troops to shoot arrows into the waves and collect seashells as spoils of war from the God Neptune, outraged that Britain was out of his reach. Boulogne got a lighthouse from Caligula. In the sixteenth century, that lighthouse collapsed with the cliff, into the sea with a mighty roar.

Wall in Boulogne

Wall in Boulogne© Saskia Dendooven

The castle lies high above the woolly mist obscuring the quays below. Here, with the sun shining and the pavement cafés at the foot of the imposing Basilica of Our Lady, it could almost be Italy. In the museum’s catacombs, now a museum of antiquities, you can still find a Gallo-Roman wall. ‘Look’, says conservator Angelique Demon. ‘This is a piece of the foundation of what was once a 40-hectare ancient city. The harbour area added another 20 hectares. The entire complex was built on terraces. C’est assez spectaculaire.’

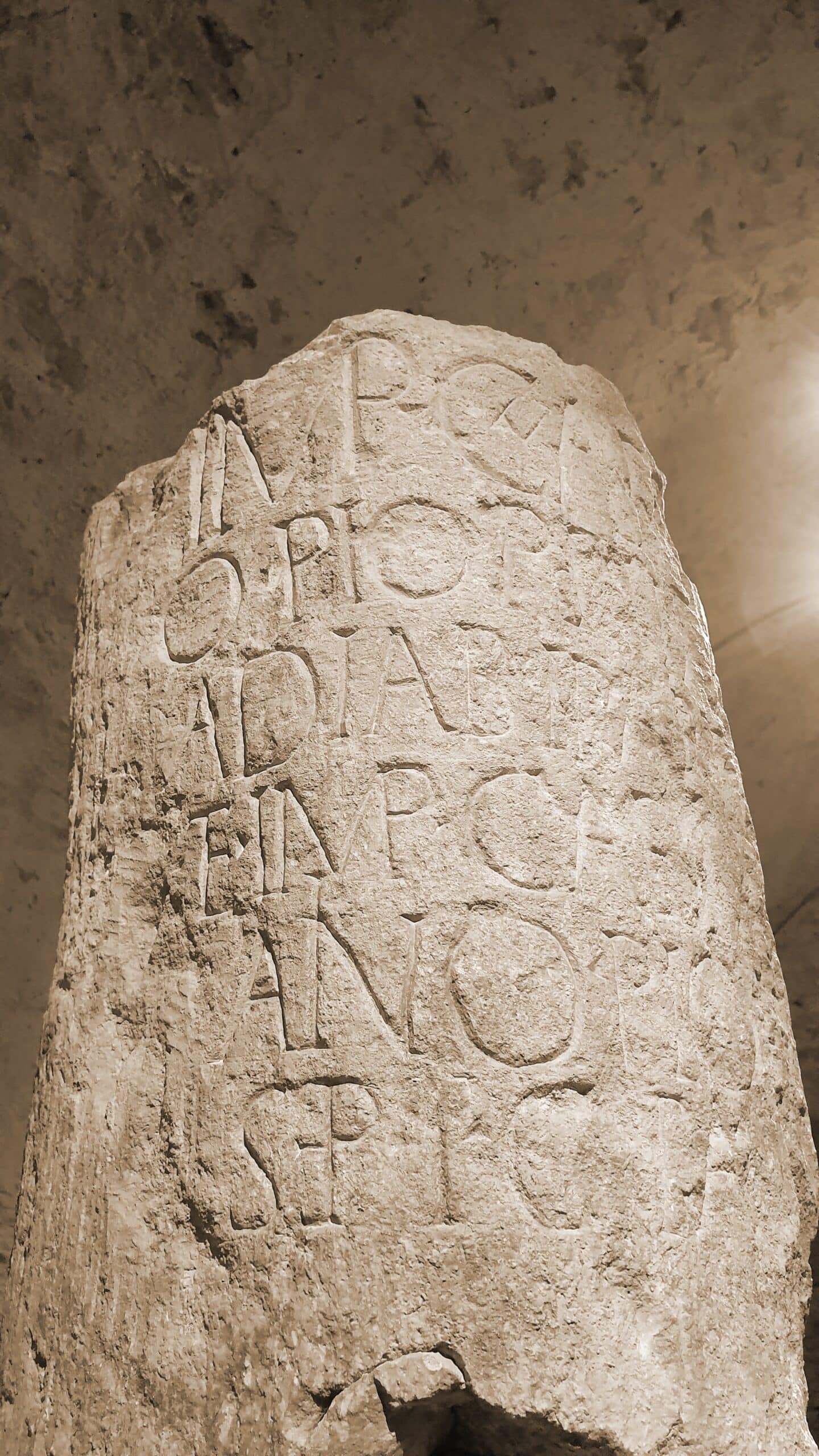

A major piece in the collection is the Roman milestone from Desvres, dating from the early third century, that was found in 2004 along a 50km trajectory between Boulogne and Thérouanne. Mile marker number 15 is, until now, the only one that has been excavated from the French part of the Via Belgica.

Angelique Demon points lovingly to the Latin inscription that translates as: ‘The distance between Thérouanne/Tervanna, 14 Gallic leuga, is dedicated to the emperor, in this case Septimius Severus (193-211).’ ‘Also very special is the sign referring to Septimius’ sons Caracalla and Geta. The latter was murdered by the former. In such cases, the rule of damnatio memoriae was normally applied: the imperial order to chisel away any references to a rival. That this didn’t happen is pure sloppiness,’ says Demon who, together with fellow archaeologist Christine Hoët-van Cauwenberghe, has conducted extensive research into the Desvres milestone. ‘You were deep in the provinces here. The inscription of the milestone is full of language errors. C’est mignon. It was clearly not the Via Appia.’

Km 54 –Thérouanne (Tervanna)

Milestone of Desvres

Milestone of Desvres© Saskia Dendooven

Boulogne, like Rome, is built on seven hills. We could have known that. When we ride out of the city to the southeast, with seagulls laughing at us, there is no sign of a classic, straight road.

Riding the Via Belgica is a solipsistic exercise: you can only be sure of your own thoughts; the world outside might not even exist.

Once past the Industrial Zone, the landscape becomes fluorescent green and we pass the hill town of Samer. Ten kilometres further, in Desvres, the local supermarket is our milestone for provisions. From this point, the Via Belgica lies under the neatly asphalted and not very busy D52 – they don’t really do bike paths here. The Boulonnais immediately becomes one of the most beautiful parts of our route: a landscape of hedgerows with hardly any villages. The road winds like a pale grey caterpillar towards the horizon. Here and there a meter-high statue of Christ interrupts the emptiness.

What the sparse remaining mile-markers, like that of Desvres, teach us is that the Romans in Gaul used both the Roman mile and the Gallic leuga as measures of distance. One mile was equivalent to a milia passuum, a thousand (double) steps (or 1,500 meters). The Gallic leuga was 1,500 paces (2,200 meters). Useful information for the legions and merchants, whether on foot, or by carrus, carpentum, rheda of raeda, petorritum, cisium, capsum or other noisily rumbling conveyances. Bicyclists in 2020 can plan their route along the Roman roads at Omnes Viae and ORBIS using the Peutinger Map and the distances on the Antonini Table.

In cosy Thérouanne on the fledgling Lys, the capital of the Civitas Morinorum, the Roman Morin district, shines a brand-new building: the Morinie Centre. A three-member team awaits us. Archaeologist Vincent Merkenbreack is connected to the University of Lille and has come here to meet us. Wild moustache and whiskers: an old Belgian! ‘I am a Nervii,’ he says – referring to a powerful Belgic tribe in northern Gaul at the time of the Roman Conquest. ‘I was born in Bavay, the main junction on the Via Belgica. I wanted to be an archaeologist from the time I was a teenager: no wonder, with a Roman forum up the road and two archaeologists as parents. Thérouanne is my heart’s delight. It’s incredible what you can find in the ground here.’

Ebblinghem

Ebblinghem© Saskia Dendooven

In 1553, an outraged Charles V commanded that Thérouanne – then a French enclave in Artesia – should be demolished to the last stone. That meant that the Roman remains here are lying under five metres of built-up medieval rubble. ‘Oui, Vincent costs us a great deal of money,’ says mayor Alain Chevalier, who has come to join us, smirking. ‘I have seven running requests for funding for archaeological digs. And, by the way, did you know that we are going to open a pilgrims’ route to the Westhoek in Belgium? Thérouanne was once the main city in the bishopric to which Ypres belonged.’

In his free time, Vincent is also a Centurion in a Roman legion. He shows us the tiny museum: a statue of Mercury, the capital from an ancient building, a strigilis to wipe away the sweat after your visit to the bathhouse. ‘The House of the Morinie is also a neighbourhood community centre, with administrative services, meeting space and even a health centre. How much more closely can we connect people with their heritage,’ he asks. ‘Similarly, our excavations also belong to this community. That’s worth some government money, isn’t it?’

Km 78 - Cassel (Castellum Menapiorum)

We ride along the narrow D109 through the land of the Menapii – the ancient Flemish, in other words. Past the railroad tracks at Ebblinghem, we hit a dirt road that disappears into a meadow. But after a few kilometres of bumping over gravel – rather uncomfortable on thin bicycle tires – the old road reconnects to asphalt, the busy D933. Just before Cassel, the road becomes a steep, medieval road that leads directly to the marketplace.

Porte d'Air in Cassel

Porte d'Air in Cassel© Saskia Dendooven

Motorcyclists and bicyclists crowd the cafés: this is the mountaintop of Les Flandres. Before the Romans appeared, Castellum Menapiorum was an oppidum (a fortified area). Caesar made it the capital city of the new Roman Civitas Menaporium. The view over the valley spans 50 kilometres. Seven cobbled, Roman roads fan out in all directions.

The trajectories of the new viae partly follow the old Gallic or Celtic paths, says Professor Frank Vermeulen from the University of Ghent, in his research on the Roman road system around Castellum Menapiorum. The entire network was locally connected at its midpoint with roads leading from the various civitates such as Cassel, Bavay and Tongeren. The roads were paved with local materials: sand, Tournai limestone, metal slag… the archetypical paving you might imagine being used on highways was rare in Northwest Gaul.

Km 166 – Tournai (Turnacum)

After Cassel, the route passes through one vicus (settlement) to another along the border of the lovely Flemish hill country. The vineyards on the south side of the Kemmelberg evoke southern memories, sloping hills lead to small-scale agriculture. An ideal environment for Roman villas, much like in South Limburg?

One example was uncovered in 2006 near Belle (Bailleul), another in 2019, in a potato field near Nieuwkerke. ‘Both were emergency evacuations,’ says conservator Johan De Schieter of the Archeocentrum Velzeke. ‘Crop marks and soil marks on aerial photos can suggest that “something” is under the surface of a field or meadow. On the basis of such photos, excavations are begun, but after a while they’re abandoned because the landowner or the government wants to make use of the land.’

There is no longer any trace of either villa. Nor, past Bailleul, any trace of the Via Belgica, except for one lonely “Heirweg” street sign in Nieuwkerke.

View from the Casselberg

View from the Casselberg© Saskia Dendooven

Across the green fields is the outline, far in the distance to the south, of the towers of the EuraLille train station. And we can also see Wervik (Viroviacum), in the past an important settlement. The local historical societies usually arrange a Gallo-Roman weekend event every two years, but not now. Beyond that, is the metropolis of Lille. We can skip over it, because there is not yet a Rue des Romains in the entire agglomeration.

There is, however, a handy canal – with a cycle path – from Roubaix to Espierres that will take us smoothly upstream to Tournai. And it’s only from there that Greater Belgium echoes again, and we’ll ride, crunching in the grit of the Via Belgica on its way to Bavay.