Cycling With the Romans through Greater Belgium: From Heerlen to Cologne

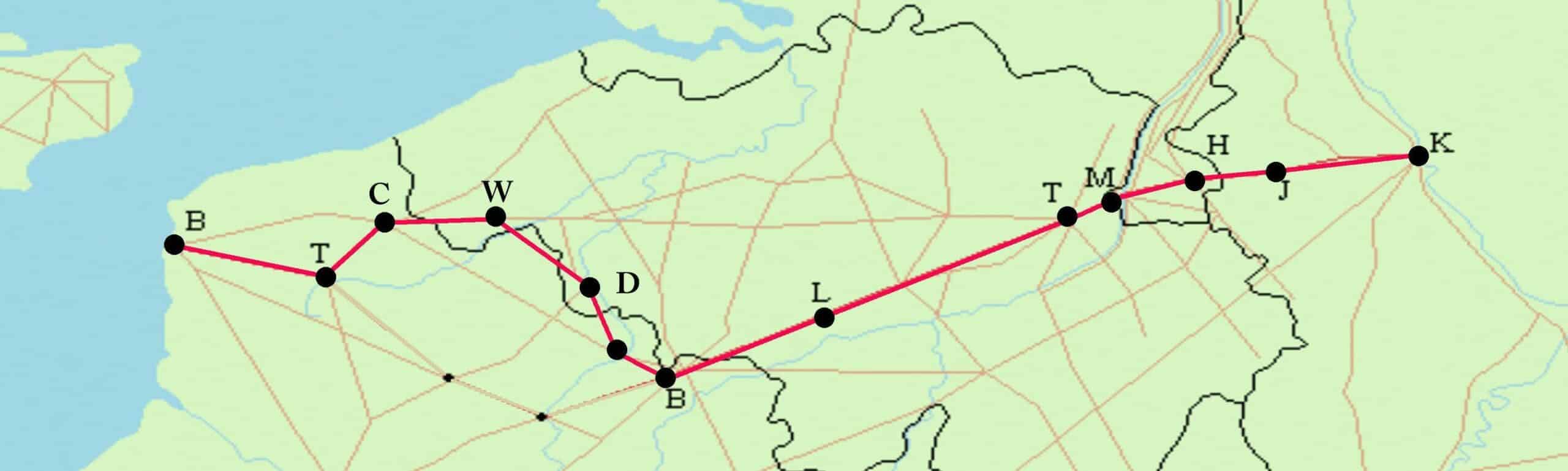

Wieland De Hoon is on the trail of the ancient Roman road from Boulogne to Cologne. He’ll be cycling 450 kilometres along the Via Belgica through Northern France, Flanders, Wallonia, South Limburg and North Rhine-Westphalia. This week: from Heerlen to Cologne.

Via Belgica

Via BelgicaKm 403 – Heerlen (Coriovallum)

The Rhine comes into view. That’s as it should be from the top of the Carl Alexander Bridge. The 200-metre-high wooded hill, looming over the Dutch-German border, promises us a Via Belgicaturm and a view over the Roman road; just as we once experienced (see part 1) from the heights of Cassel (Castellum Menapiorum). But it is 35C and we have no energy left, so we skip the climb.

Replica of a Jupiter column on the Sophienhöhe

Replica of a Jupiter column on the Sophienhöhe© Saskia Dendooven

This former dump is an attractive beacon in the flat landscape. ‘The lignite mining industry benefits the archaeological excavations here,’ says Christoph Fischer of the Citadel Museum in Jülich. ‘There are currently three open pits where research is taking place, such as in the gigantic Tagebau Hambach coal pit.’ Complete villages were cleared away, but many treasures were found. On the highest hill, the Sophienhӧhe (302 metres), just past Jülich, is a fake Roman watchtower. This is a bizarre landscape. Here, the original Via Belgica lies under hundreds of metres of lignite waste. Set in the middle of boring fields full of windmills, the hills offer an unexpected foretaste of Eifel, looming on the southern horizon.

What lignite was to this part of North Rhine-Westphalia, coal was to the former mining town of Heerlen (Coriovallum) in South Limburg. That is where we started the last phase of our journey this morning. In Coriovallum the Romans built a large bathhouse. It was a busy crossroads: good roads led to Tongeren and Cologne, but also to Xanten (the mighty Castra Vetera) and Trier (Augusta Treverorum), outposts for continual, doomed Roman invasions of Germania Magna and incursions against the long-haired, savage inhabitants of the eastern bank of the Rhine.

Coriovallum must have been the site of the continuous comings-and-goings of military transports. ‘Legionaries of the Legio V built this bath house,’ explains curator Karen Jeneson of the Roman Baths Museum, the largest Roman excavation in the Netherlands. ‘It was primarily for the use of the officers.’ The ingeniously designed bath house with its laconicum, tepidarium and caldarium heated by a hypocaustum, is completely covered. Through the prestigious renovation of the museum, the former mining town of Heerlen hopes to put its Roman heritage on the map.

Roman Baths Museum in Heerlen

Roman Baths Museum in Heerlen© Saskia Dendooven

‘In the nineteenth century, rich mine owners and priests busied themselves with amateur archaeology,’ says Jeneson, who walked for five days on the Via Belgica, from Tongeren to Cologne while doing her doctorate. ‘In 1877, a chaplain dug up a clearly indigenous goddess statue here; the Heerlen Minerva, which I think is one of our most fascinating pieces. Such finds used to end up in the National Museum in Leiden, but since we founded our own museum in Heerlen in 1975, we have put ourselves on the map as a Roman city.’ This was thanks to the approval of some South Limburg entrepreneurs, who eagerly jumped on the carrum to market this Gallo-Roman city. ‘Made in Coriovallum’ is a profitable idea here. The VIA project is an example of how combining tourism and catering (‘Taste our Roman spelt pancakes’) with culture, technology, design and small-scale agricultural archaeology, makes archaeology more attractive to a wider audience.

As a cycling route, the Via Belgica really lets us down by being pretty ugly between Heerlen and the German border. In fact, it has been like this since Maastricht. No straight stretches, rarely unpaved and running through fields and woods; plenty of housing developments and busy roads lined with very un-Dutch death tracks in place of proper bike lanes. It is almost as if we are back in Valenciennes, though without the sorrow and shards of glass. But past the Landgraaf slap heaps we make a lovely discovery on the Haanweg, under the bridge of the A29: The interior of the bridge is one large work of art dedicated to the Via Belgica, a project of the Landgraaf foundation Linea Recta. We are certainly on the right track. From here onwards, the landscape unfolds into a pleasant, rolling Roman vista towards Rimburg.

Under the bridge of the A29, near Landgraaf

Under the bridge of the A29, near Landgraaf© Saskia Dendooven

The villages in the area have produced some impressive finds. In the unsurpassed four-volume History of the Low Countries (1970), master storyteller Jaap Ter Haar describes Simpelveld’s ash chest, made of sandstone, which contains a dedication chiselled by a grieving husband to his deceased wife: IVNONI MEAE

– to my Juno. Ter Haar tells us ‘a skilled sculptor – possibly from Cologne – was commissioned to decorate the inside of the chest with reliefs.’ He has chiselled a woman on one wall. ‘She’s on a couch, sitting half-upright, observing her surroundings. Is it Juno?’ The woman is surrounded by her household, in her trusted environment. ‘The love of Juno’s husband must have been quite intense,’ Ter Haar supposes. The ash chest – which can be seen in the Roman Baths Museum – was found in 1910, in Stampstraat in Simpelveld.

Juno?

Juno?© Saskia Dendooven

Km 438 – Jülich (Iuliacum)

On the way to Jülich (Iuliacum), past the Wurm, the brook that marks the border, we continue further along the left bank of the Rhine just inside Gallia Belgica. In Roman times, the Rhine was often ‘our’ eastern border. The later Duchy of Jülich (1356-1794) was a transitional area in Limburg. Perhaps the most remarkable period was the short-lived Cisrhenian Republic (1797-1802), founded by revolutionary France, which absorbed Jülich and used the Rhine to neatly mark the border all the way to the Netherlands. The French-Belgium occupation of the Rhineland restored the Roman limes: after 1,800 years the Rhine once again marked the eastern border of Gaul for a while. And yes, Caesar would have smirked. The idea of a Greater Belgium is just as full of holes as the Via Belgica itself because it quickly leads to musings about a Union-of-Dutch-Nations or the All-Dutch-Ideal. Irredentism lends itself perfectly to casual summer reflections.

That Germany takes its stretches of the Via Belgica seriously is proven by no fewer than three information panels and even a marked VIA cycle junction route. Between Ubach-Palenberg and Jülich the track of the Via Belgica

is a mess, even though we come across an old friend in Baesweiler where the Brünestraße brings us back to the Chausée Brunehaut.

Christoph Fischer (Museum Zitadelle Jülich) shows a life-size replica of the original Via Belgica

Christoph Fischer (Museum Zitadelle Jülich) shows a life-size replica of the original Via Belgica© Saskia Dendooven

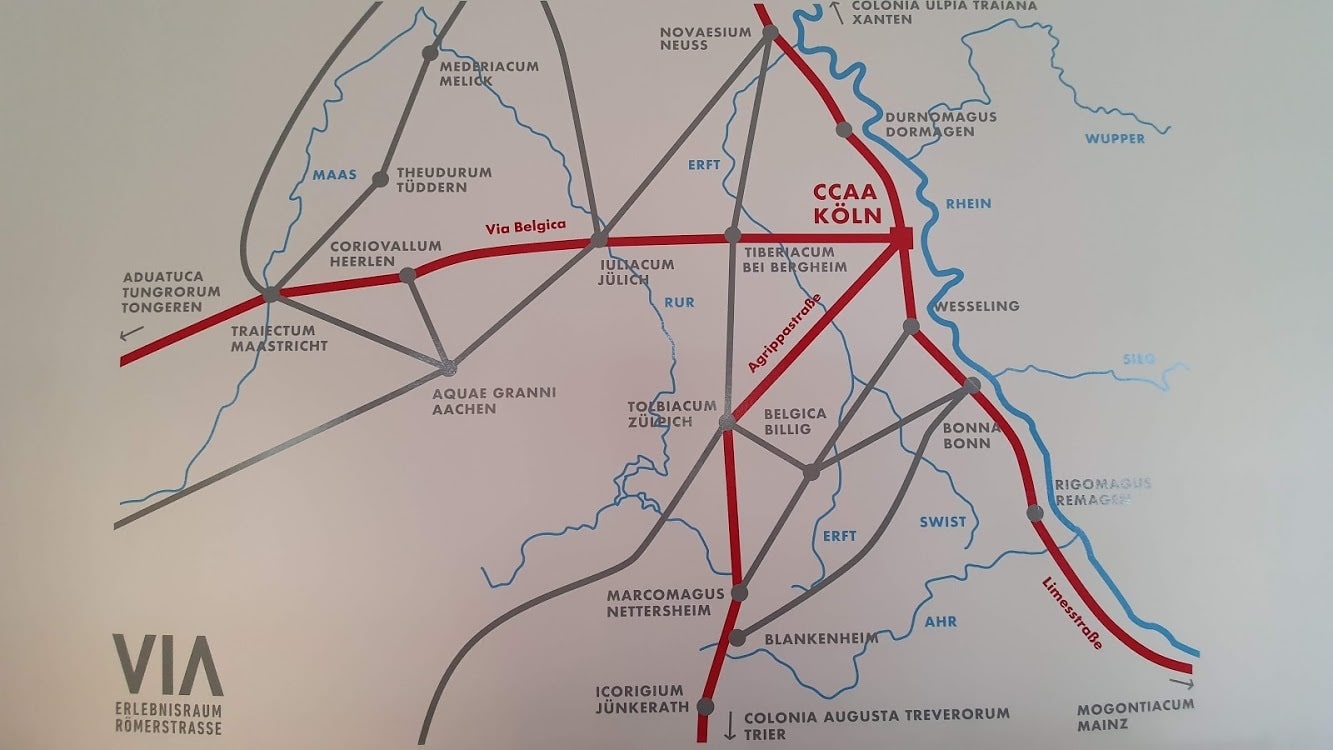

The small Citadel Museum in Jülich is housed in the 16th century citadel of the Dukes of Jülich. A special Erlebnisraum Via Belgica (Via Belgica Experience) has been created. We take a peek at the interesting plinth of a Jupiter column with the inscription Iuliacum – proof of the existence of the vicus that stood between Heerlen and Cologne. Christoph Fischer shows us a life-size model of the Roman road, which in places could be as much as 24 meters wide: the same as a modern highway. ‘In this region, the road was paved not with tiles, but with local materials such as gravel and loam clay. Our research is done in collaboration with the museums of Cologne, Aachen and Heerlen,’ says Fischer. ‘And we also have a good working relationship with the lignite mine operators.’

The Via Belgica in Elsdorf

The Via Belgica in Elsdorf© Saskia Dendooven

But there is no loam clay in store for our bike tires after Jülich, though there are a few nice, old-fashioned, straight, easy-to-cycle stetches of the Via Belgica paved with gravel or concrete slabs on the route to Elsdorf and further on to Bergheim. Near the Sophienhӧhe we even see a group of four milestones, one of which is Roman: a replica of the Milestone of Zülpich, set up by order of the Emperor Constantine (306-337) and the only one in Germany. Milestone porn! Then the fun is all over. We are approaching Cologne and have to fit the puzzle pieces together ourselves, until we end up on the busy Aachener Straße where we are finally heading into the centre of Cologne. In Weiden we pass the impressive Roman burial vault Römergrab Weiden: not to be missed, but, alas, it has just closed. And, finally, we reach the end of our gruelling east-to-west journey at Cologne’s decumanes maximus and, at long last, the Rhine.

Milestones on the Sophienhöhe

Milestones on the Sophienhöhe© Saskia Dendooven

Km 485 – Cologne (Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippina)

That Cologne’s city map remains so clearly Roman in form is thanks to the engineers of General Marcus Vispanius Agrippa (63 BCE – 12 CE). This personal friend of the Emperor Augustus wanted two large military connections to appear – and quickly – the first from Cologne to the Gallic capital Lyon (via Trier and Metz) and the second to Boulogne. Agrippa had measurements taken, wrote the Commentarii Geographi and displayed a world map in the portico of his villa.

He was a man after our own hearts because we owe our cycling journey to him. And Cologne owes him its name because his daughter-in-law was named Agrippina, and of royal blood: she was at once the sister of the crazed Caligula, the wife of the stuttering Claudius and the mother of nefarious Nero. In 50 CE, the city that was first called Oppidum Ubii – the fortress of the Ubiërs, the tribe that lived in the area – was named after her: Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippina or, in a nutshell, CCAA. For the average Gallo-Roman, a trip to CCAA must have been something like a flight to JFK today: pretty impressive.

© Saskia Dendooven

Our journey ends at the Belgisches Haus on the Cäcilienstraße in Cologne. This is where the temporary exhibition concerning the renovation works on the closed Romano-German Museum is housed. We are met by a squadron of local, blond, uniformed female attendants who formally direct us from one room to the other with steady hands. It is a fitting ending. Votive stones, a Nehalennia altar, terra cotta reliefs of Gallo-Roman matrones with Ubish hairstyles and a gravestone for the 8-year-old Bella from Dururocortum. An honour guard of Roman imperial heads bows us out.

For us, the Via Belgica ends with a half-pint of Hellers Weizen beer on the terrace of the Bootshaus Albatros and a view of the Rhine bridges. The riverbank beaches are full. There’s a party going on under one of the bridge pylons, with nary a face mask in sight. We cycle around it and think of the legionary’s inscription that stands furthest from Rome. IMP DOMITIANO CAESARE AVG GERMANICO LVCIVS IVLIVS MAXIMVS LEGIONIS XII FVL: Under Emperor Domitian, Caesar, Augustus Germanicus, Lucius Julius Maximus, Legio XII Fulminata. It’s location? Qobustan, 69 kilometres south of the Azerbaijani capital Baku.