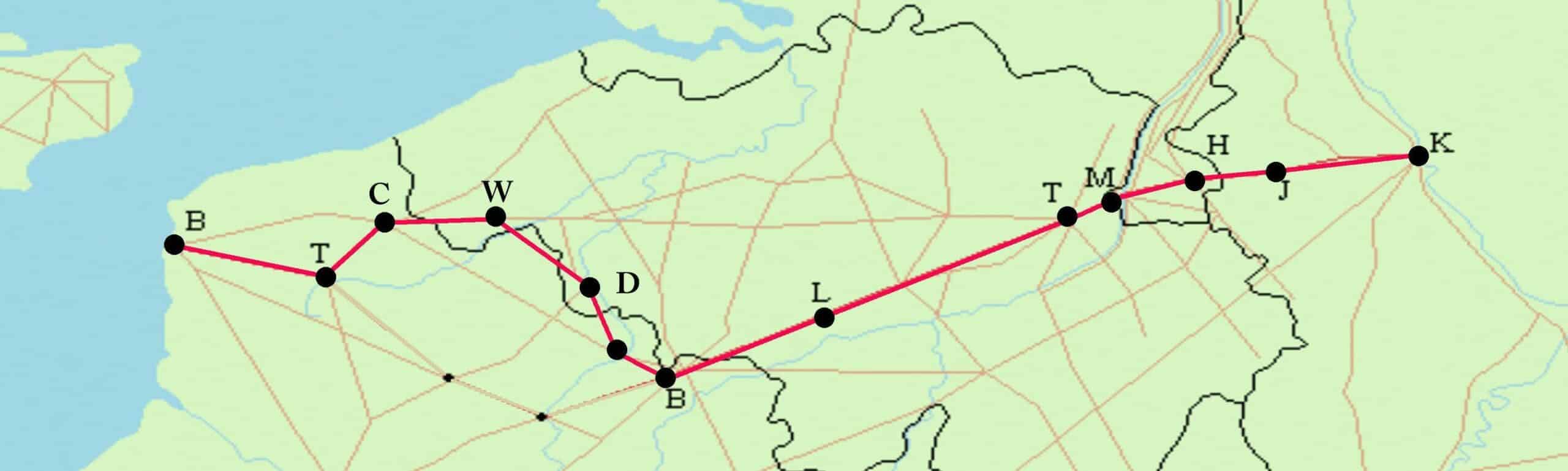

Cycling With the Romans Through Greater Belgium: From Liberchies to Heerlen

Wieland De Hoon is on the trail of the ancient Roman road from Boulogne to Cologne. He’ll be cycling 450 kilometres along the Via Belgica through Northern France, Flanders, Wallonia, South Limburg and North Rhine-Westphalia. This week: from Liberchies to Heerlen.

Via Belgica

Via BelgicaKm 274 – Liberchies (Geminiacum)

Liberchies

Liberchies© Saskia Dendooven

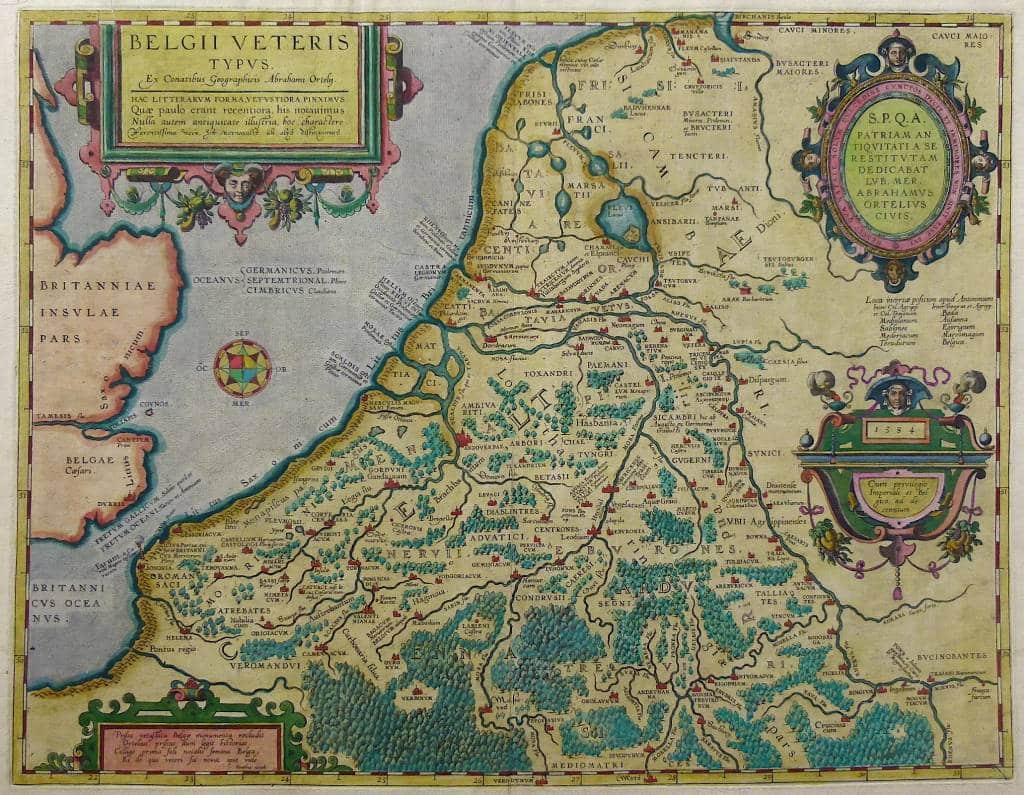

Dust and an endless view of fields of grain. Tongeren is a long day’s ride past the horizon when we saddle up on a sunny morning in Liberchies, near Charleroi. The open fields catapult us back two thousand years in time. On the way from the North Sea to the Rhine, we leave the gloomy coal wood – the Silva Carbonaria – at Geminiacum far behind. The Belgii Veteris Typus map (1584) drafted by Antwerp cartographer Abraham Ortelius sketches the contours: still remaining are the woods and forests of Mormal, Houssière, Halle, Soignes and Meerdaal. This is where the Texas of Gallia Belgica begins, where expansive gentlemen’s farms ensured a constant supply of stock and agricultural products to the Rhine region.

The Belgii Veteris Typus map (1584) drafted by Antwerp cartographer Abraham Ortelius

The Belgii Veteris Typus map (1584) drafted by Antwerp cartographer Abraham OrteliusBecause we rarely cycle through any villages on this stage of the journey, it seems to be the most authentic piece of the road, although there is not really much to see. On the town square of Liberchies the museum is closed indefinitely. Still, Geminiacum

is a jewel in the crown of the Roman road. ‘In 1970, a treasure trove of 368 golden Roman coins was found,’ says Johan Deschieter of the Velzeke Archeosite. ‘Liberchies and Braives (Perniciacum), a day’s march further ahead, are two vici that are that are substantially documented by the universities of Leuven and Louvain-La-Neuve. For archaeologists, that documentation serves as reference material.’

Sombreffe, on the border between Hainaut and Namur

Sombreffe, on the border between Hainaut and Namur© Saskia Dendooven

Liberchies-la-Romaine – we’ll call this cobblestoned village by its honorary name – does not seem to offer much to the casual visitor, despite the fact that there was a castellum measuring 54 by 45 meters in the nearby hamlet of Brunehaut. Here, the Roman Empire exists only in our imagination. The deserted road represents a kind of in-between time, with only a straight beacon to the horizon providing insights into a complex, ancient world. All the ancient characters are merely dust on the roadway. The summer breeze blows chaff and two millennia of silence in our faces.

The cruel N5 near Bons Villers hacks the Via Belgica mercilessly in two. We get through with the help of tricks, acrobatics and Google Streetview. Afterwards, we cycle traffic-free about ten kilometres further – mostly off-road – over dirt tracks lined with telephone poles. Only one place, the lonely Brasserie de Bertinchamps, offers protection from the summer sun. It’s a welcome mansio

(waystation) along the Via Belgica.

Km 332 – Braives (Perniciacum)

After Gembloux, there are some turns in the road and the first tumuli appear. They are like pustules in the landscape, high burial mounds overgrown with deciduous trees, dating from the first century; although burial fields from the Bronze and Iron Ages can also be found here. The burial mounds were built next to the new highway from Boulogne to Bavay. The Civitas Tungrorum is littered with them. When we pass the tumulus of Hottomont, 11 meters high and 50 meters wide, we decide to venture into the surrounding potato field to take a look.

Between Geminiacum (Liberchies) and Perniciacum (Braives)

Between Geminiacum (Liberchies) and Perniciacum (Braives)© Saskia Dendooven

We scramble through the tree roots and dry grass. There is no denying that these tumuli were useful vantage points. The Journal of the Voyage of Philippe de Hurgas to Liége and Maestrect in 1615 (La Voyage de Philippe de Hurges à Liége et à Maestrect en 1615) certainly says so:

Les motes servent encore à ceux du voisinage […] et à ceux qui cerchent les levées [les routes] ou qui sont perduz ou esgarez en leur chemin, en sorte que, les voiants, ils se recognoissent aussitost et voient où ils doibvent tirer, si bien que si l’on n’est sot, yvre ou aveugle, on ne se peut perdre ny fourvoyer, de jour ou au clair de la lune, en ces cartiers.

You would have to be crazy, blind or drunk to get lost here.

The track through the fields meanders slowly further eastwards through this tumuli landscape. After Awenne and Braives, the asphalt reasserts itself from where the crossing of the Route de Namur in Hainault and the Via Belgica

becomes the increasingly busier N69 – right up until Tongeren. From the Roman Cobblestone in Koninksem with its multiple housing developments, the very last tumulus we pass looks like a large molehill, but sure enough: it is conveniently treeless and thus shows its original state.

Near Braives (Perniciacum)

Near Braives (Perniciacum)© Saskia Dendooven

Km 362 – Tongeren (Atuatuca Tungrorum)

Statue of Ambiorix in Tongeren

Statue of Ambiorix in Tongeren© Saskia Dendooven

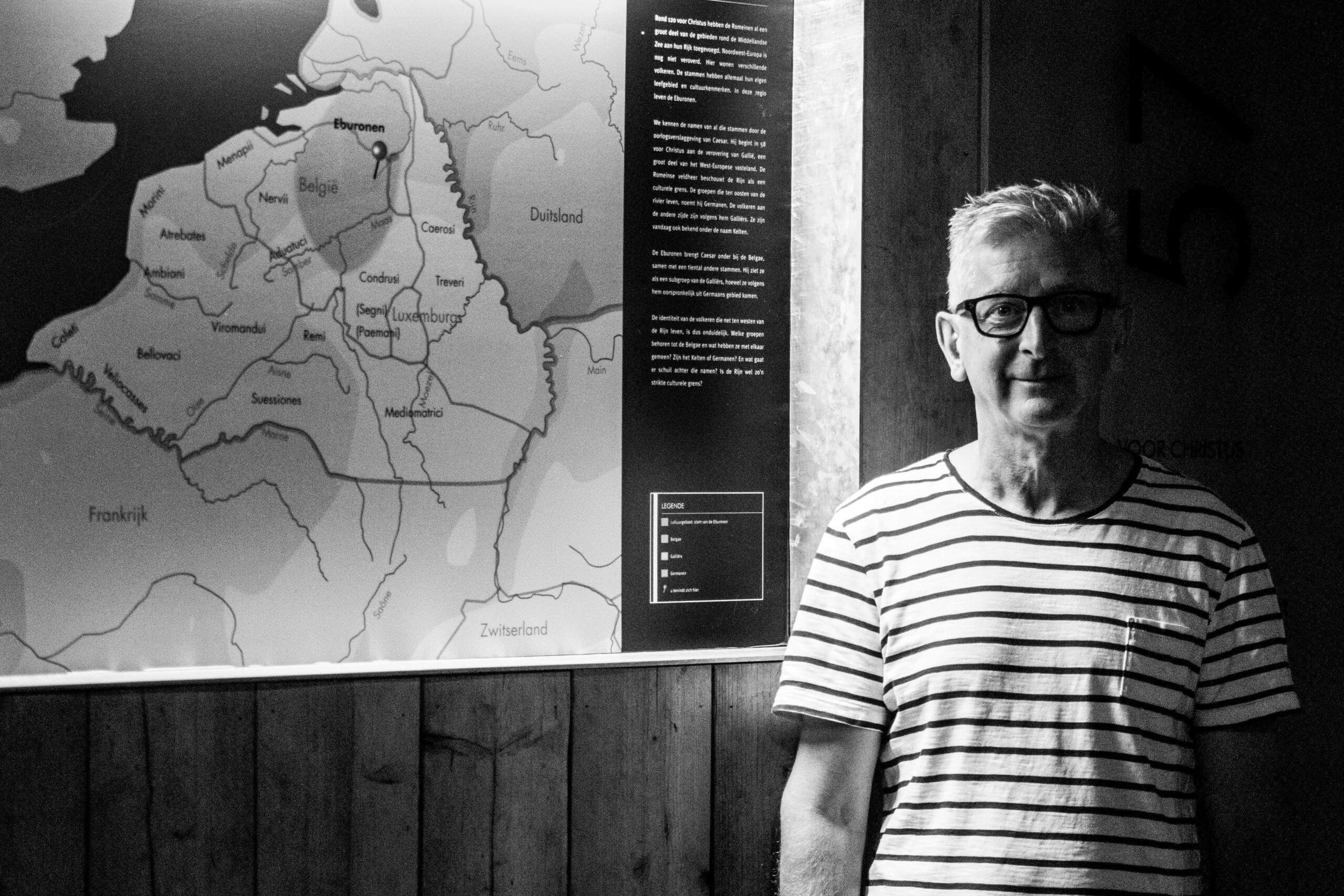

Ambiorix and his Eburones – the original Celtic inhabitants of the area – gave Caesar a few sleepless nights. The poor Morini and Menapi in the west were guerrilla fighters who hid in the woods and marshland near Boulogne and on the Flemish plain, but Ambiorix with his fiery temper was not enamoured of Roman tax collectors. He unleashed a massive uprising in 54 BC that destroyed an entire Roman legion and five cohorts. Caesar’s revenge was – not surprisingly – horrific: the Eburones were, as a tribe, simply annihilated. After this uprising, Tongeren grew into the one truly significant Gallo-Roman city (municipum) between Boulogne and Cologne. Within its second-century, 4,500 metre-long defensive wall, the city was substantially larger in Roman times than in the Middle Ages.

Roman Tongeren

Roman Tongeren© Saskia Dendooven

We were awed by the huge model of Roman Tongeren in the city’s Gallo-Roman museum. The collection is impressive. ‘Tongeren was, first and foremost, a market; a forum, with a temple, a Jupiter column, a basilica…,’ says curator Guido Creemers. ‘It’s likely that there was also a huge, filthy cattle market here. The proximity of the Jeker River (still navigable in Roman times) was crucial for transport using flat-bottomed boats that could easily reach the Meuse.’ The Tungri, the mixed Germanic-Roman population that took the place of the Eburones, had a warlike reputation. ‘There were Tungric cohorts stationed at the Northern English fort Vindolanda, near Hadrian’s Wall,’ according to Creemers. ‘Tongeren itself did not have a large garrison; we haven’t found much in the way of military remnants here. But we want to bring some attention to this aspect of life in an upcoming exhibition.’

Guido Creemers, curator of the Gallo-Roman Museum in Tongeren

Guido Creemers, curator of the Gallo-Roman Museum in Tongeren© Saskia Dendooven

Tongeren did not have much need of the legions. Unlike Bavay, that other Via Belgica

junction, Atuatuca Tungrorum reinvented itself after the Romans left, becoming, in the fourth century, the earliest centre of Christianity in Belgium, thanks to the efforts of the first bishop in the Low Countries, the Armenian Servatius. But things could have been even better: when Servatius moved to the safer Maastricht, the bishop’s see, and eventually to Liège, Tongeren’s days as an important Roman trading centre came to an end.

Km 379 – Maastricht (Mosa Trajectum)

Tongeren ushered in civilisation from west to east and the character of our cycling trip also underwent a change at this point. The landscape became more densely populated, the roads busier. Even in Roman times, the villas and vici were significantly closer together as they neared the Rhine region. We followed the Roman road from Herderen to Riemst, where the local historian Peter Neven wants to put the Via Belgica on the map. There is a precedent: the Via Belgica Digitalis project wants to map every community along the Via Belgica in the province of Dutch-Limburg. Riemst wants to be part of this initiative. ‘I’m not sure that will be possible for the time being,’ says Tongeren city archaeologist Dirk Pauwels. ‘It is essentially a matter of local governance. The Gallo-Roman Museum has been a municipal museum since 2018 but there are also the provincial and Flemish considerations. And then, for a project like Via Belgica, interregional and international collaborations also have to be involved. Finally, Tourism Limburg’s current focus is on the new Fruit Region Railway bike path between Tongeren and St. Truiden.’

Carving 'The Entry of Romans in Mosa' (1931) in Maastricht

Carving 'The Entry of Romans in Mosa' (1931) in Maastricht© Saskia Dendooven

This must have been one of the most fertile areas of Gallic Belgica: the number of Roman villas, often built by veterans from legions such as the Legio I Germanica

or the Legio XY Primigenia who received parcels of land here near the Jeker River and, further up the road, along the Geul, is significant. This villa landscape provides clearer evidence of Gallo-Roman chic – certainly based on the size of the buildings – than the western provinces. Terra Sigillata

(stamped red clay) pottery, glassware, olives and wine from the Mediterranean were snapped up here by customers with more money to spend on luxuries than those further west near the coast, where laboriously extracted salt and sheep’s wool offered by the Menapian poor were the principal means of exchange.

When we cross the Meuse at Mosa Trajectum, we have to make our way through the masses of shoppers that crowd the cafés. Maastricht was home to an important Roman castellum, a Temple of Jupiter – the foundations of which are under a modern-day hotel – and an ingenious wooden bridge, though at first sight, there are no recognisable traces. Happily, in the Griendpark, there are still two 1931 bridge pylons from the Wilhelmina Bridge, blown up in 1940, on which there is an Art Deco carving called The Entry of Romans into Mosa.

Km 403 – Heerlen (Coriovallum)

Navigating in the direction of Meerssen and Valkenburg is harder than expected: despite the Via Belgica Digitalis site, there is not really a complete VIA cycling route. Luckily, the old Roman road follows the Geul river valley where, on the right bank, we discover a lovely, wooded bike path to Valkenburg. We pass a few marl caves and busy campsites, while posters along the way promote ‘Roman rest stop!’ In Valkenburg in 1910, in one of the marl caves, a made-to-measure tourist attraction was created: The Roman Catacombs, an exact replica of the underground graves of the first Roman Christians.

In a normal year, this place would be full of tourists, and that is still the case in the abnormal year 2020. This is the epicentre of the southern Netherlands with its chalky soil and sunny hillsides that hide a few small vineyards. The roman writer Plinius the Elder stated in his Naturalis Historia that the local marga

(marl) was a superlative fertiliser. We scrape a path through the traffic to the road to Klimmen. Past the high hills in the land of the Meuse and the Geul, the real Gallo-Roman treasure of South Limburg beckons: Coriovallum.