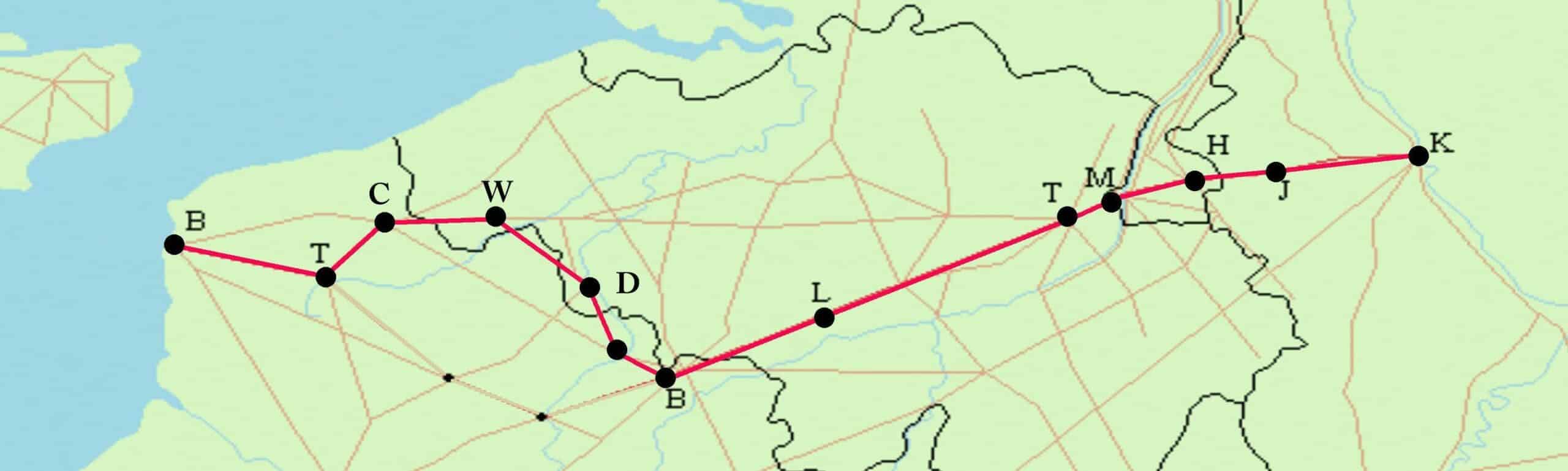

Cycling With the Romans Through Greater Belgium: From Tournai to Liberchies

Wieland De Hoon is on the trail of the ancient Roman road from Boulogne to Cologne. He’ll be cycling 450 kilometres along the Via Belgica through Northern France, Flanders, Wallonia, South Limburg and North Rhine-Westphalia. This week: from Tournai to Liberchies.

Km 166 – Tournai (Turnacum)

In the fields near Lesdain, ten kilometres past Tournai, stands the Pierre Brunehaut. A massive block of dark grey sandstone, the largest menhir in Belgium, 4,500 years old. It is a prehistoric trompe l’oeil: depending on the angle, it looks like an inverted guillotine blade, the Rocher Bayard

in Dinant or a grey finger. The early nineteenth-century graffiti is remarkable, as are the old bullet holes: whether they were made by musket or machine gun bullets, no one knows. For those who are paying attention, the Pierre Brunehaut is a magical place where prehistory, antiquity and modern history are blown together in the ageless, damp, west wind.

Pierre Brunehaut

Pierre Brunehaut© Saskia Dendooven

Here, the Roman road is a vague dirt path. We bump along the path, towards the Scheldt River. To find the route from the Gallo-Roman gate of Tournai to the D68 in France, the first intact piece of the Via Belgica, you need more than a GPS. At a roundabout on the Route de Condé in Nivelles, the road seems to just disappear – until we spy, behind a row of trash containers, a barely visible path leading into the woods. The narrow, mud-puddle-pocked path along the northside of the Wallers Wood is barely passable on a bicycle. And yet, it is still called Chaussée Brunehaut. Nearly all the patches of the Roman road in Wallonia and Northern France are called that. It is the street name with the most running kilometres.

Nearly all the patches of the Roman road in Wallonia and Northern France are called Chaussée Brunehaut

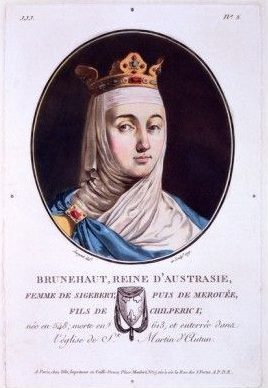

“Brunehaut” has its origin in Brunehilde (or Brunichilde) from Austrasia (534-613), a Visigoth princess. Under her rule, the Roman road was repaired, though it seems unlikely that she actually had much to do with this. How the princess met her end (and how the Chaussées Brunehaut got their name), sparks the imagination. She seems to have been put, naked, on a camel by order of the misogynist Frankish emperor Chlotar II. But after three consecutive days of this torture, poor Brunehilde still showed signs of life. Next, she was tied by hair, hand and foot to a wild stallion and dragged throughout the land. The Chaussées Brunehaut mark the traces of her grisly death – the Pierre Brunehaut marks where her body was found.

Brunehilde from Austrasia

Brunehilde from AustrasiaAnother source mentions a Belgian king called Brunehaldis. The French archaeologist Nicolas Bergier from Reims (Histoire des grands chemins de l’Empire Romain, Paris, 1622) puzzled over this, as did his later counterpart Grégoire d’Essigny (Mémoire sur la question des voies romaines, vulgairement appelées Chaussées Brunehaut, qui traversent la Picardie, Amiens, 1811). It is clear that things usually end badly for the Brunehildes. Brünnhilde, the Valkyrie of the Song of the Nibelungs (Germany, 13th

century) loses her ring and her golden belt, which is later used as proof of her adultery. In fact, things don’t really work out until 2012 when Quentin Tarantino’s Broomhilda appears in the film Django Unchained.

Km 224 – Bavay (Bagacum Nerviorum)

Meanwhile, we cycle (sort of) through the Wallers Wood. It resembles Paris-Roubaix, but the cobblestones are on the south side of the forest: we only get mud. After our toil, we reach the outskirts of Valenciennes. Desertion, decay and broken glass litter our path. Continuing towards Estreux, we escape the misery, and, after Eth, we cross the French-Belgian border again. For us, the Via Belgica

stretches through the cornfields as the Rue de la Ligne. In 1795, at house number 1, the Cabaret de la Houlette, a mass murder was committed. During home-jackings the criminal gang Les Chauffeurs du Nord, under the leadership of one Moneuse, used to hold their victims’ feet in the fire until they revealed where their gold was hidden. But in La Houlette, something went wrong, and women, babies and children were hacked into pieces with sabres. This is certainly the loneliest piece of the Roman road, with only the odd, gloomy farm along the way. The crime stories become tangible through the eighteenth-century border stones that demarcate the French-Austrian border along the road in the hamlet of La Flamengrie: any would-be criminal could have slipped smoothly over the border.

Chaussée Brunehaut in the Wallers Wood

Chaussée Brunehaut in the Wallers Wood© Saskia Dendooven

Happily, we manage to come through in one piece, reaching the safety of Bavay (Bagacum Nerviorum). Gallic Belgica was governed from Durocortorum, present-day Reims, but all roads led to Bavay. Seven routes dedicated to Jupiter, Mars, Venus, Saturn, Mercury, the Sun and the Moon, began at seven of the nine temples in the city, the pinnacle of the Gallo-Roman road network. This Bavay arose out of nothing (ex nihilo) at the outskirts of the tribal lands to become quite impressive: the largest forum in all of Gaul, along with an enormous basilica and a temple. On the excellent tour of the Antique Forum visitors learn the entire, surprising history. In the sweltering July heat, the ruins of the red-blue arch vaults shine as they should. Only the chirping of the Mediterranean crickets is missing.

© Saskia Dendooven

It is from Bavay that the only diverticulum (side street) promoted to tourists departs: the road to Velzeke. Along this road is the archeosite at Aubechies with its replica Roman villa. ‘Our Roman road serves as an obvious incentive for more cooperation within Belgium,’ says Director of the Antique Forum, Véronique Beirnaert-Mary. ‘We have been organising exhibitions and events on both sides of the linguistic border for ten years. In this way we can provide the public with an overall picture of the region. Yesterday we received a group of Flemish cycling tourists. There are Belgians advocating for a UNESCO label for the Via Belgica, but the few historical remains make it difficult. On a European scale there is a clear movement to protect the Roman roads. I hope for success because what we are doing here in Bavay is important in order to make our residents aware that the Romans of Bagacum were their ancestors and that it is possible to bring those times to life again.’

Km 253 – Waudrez (Vodgoriacum)

After 30 kilometres (a day’s march for a legionary) on a lovely, rolling Roman road – complete with a residual Coal Forest or Silva Carbonaria at Malplaquet – we arrive, still in one piece, in Waudrez. In the vicus (settlement) Vodgoriacum

we find the Statio Romana, the local Gallo-Roman museum. Time to change horses and drink a jug of cervoise (Gallic beer) or hydromel (a honey-based aperitif). Curator, president and Roman “senator” Philippe Dekegel takes the lectern. Dekegel founded the local museum in 1969 and in the five decades since, has created an impressive life’s work. ‘We’ve uncovered thousands of Roman artifacts,’ he says, ‘and we are far from finished.’ The wider surroundings remain unexplored from an archaeological perspective, as proven by the discovery of the Péronne-Lez-Binche milestone, barely a kilometre from Vodgoriacum. This milestone, erected in the reign of emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161), is slightly older than that of Desvres, near Boulogne.

‘Ah yes, the milestone,’ says Philippe Dekegel. ‘The municipal workers toke the stone to the museum of Mariemont. Even though it was found in our vicus.’ This typifies the passion for recognition that Dekegel has been chasing for fifty years. As the sole chairman of a non-profit organization – in amongst all the other provincial or regional museums with Roman collections – he emphasises time and again how everything in his Statio Romana has been scientifically substantiated. Dekegel was formerly an industrial design teacher, and he still practices his other job as a surveyor. He shows us his groma: a Roman surveying tool used in the construction of roads and buildings. This is a long staff with four horizontal arms placed perpendicularly to each other used to plot straight lines and right angles, and thus also define square and rectangular boundaries. It is due to this instrument that the Roman roads and architecture were so straight. Dekegel also shows us his chorobates, used by the Romans to measures gradients.

Philippe Dekegel in his 'Statio Romana'

Philippe Dekegel in his 'Statio Romana'© Saskia Dendooven

The sleek urban design of the Roman period is… well, a thing of the past. As we cycle further towards the northeast, the landscape changes. Le Centre welcomes us with the visual clutter of grey streets, gas stations and roadside pizza joints. The Roman road network may be the largest monument to antiquity, but we do not see any tumuli; only overgrown slag heaps. We keep our eyes peeled for billboards advertising Gauloises cigarettes, the famous cigarette brand with the Gallic winged helmet. But we are apparently a few decades too late for that. Nobody smokes anymore, not even here in Le Centre, Belgium’s ‘black lung’, the historic coal country. In addition to the Borinage, this region was the economic lifeline of the fledgling Belgium. But the majestic castle grounds of Mariemont were here long before the coal mines. In the museum, visitors can see the milestone of Péronnes-Lez-Binche, but also the Merovingian jewels from the royal necropolis of Trivières and some Gallo-Roman bronzes from Bavay.

Km 274 – Liberchies (Geminiacum)

No, Gauloises are no longer smoked in Le Centre, nor – we suppose, as we enter a fantastic, hospitable and, yes, loud, Italian bistro – in Morlanwelz, the Walloon ‘Little Italy’. The tortellini della casa with ham and peas is a work of art! Rome doesn’t always have to have the flavour of antiquity. Ahead of us lies Liberchies (Geminiacum), but first we must pass through the housing developments and garage plots of Chapelle-lez-Herlaimont and Trazegnies, and over fields dominated by high-voltage electricity pylons along the E42 highway near Courcelles. We pass the SOS Décès mortuary and avoid getting any punctures from the illegally dumped building rubble on our neglected road, which is neatly marked with mossy green signs saying ‘Chaussée Romaine’ – though it seems no one has passed by here for ten years.

Chaussée Brunehaut in Morlanwelz

Chaussée Brunehaut in Morlanwelz© Saskia Dendooven

We can feel the effects of the limoncello offered by our flamboyant restauranteur in Morlanwelz – we make bets that his name is Tony Montana. But we’ve had enough for one day. Liberchies – the vicus Geminiacum, known for its Roman coins – is located next to Luttre station, and that is precisely where we call an end to this second stage.