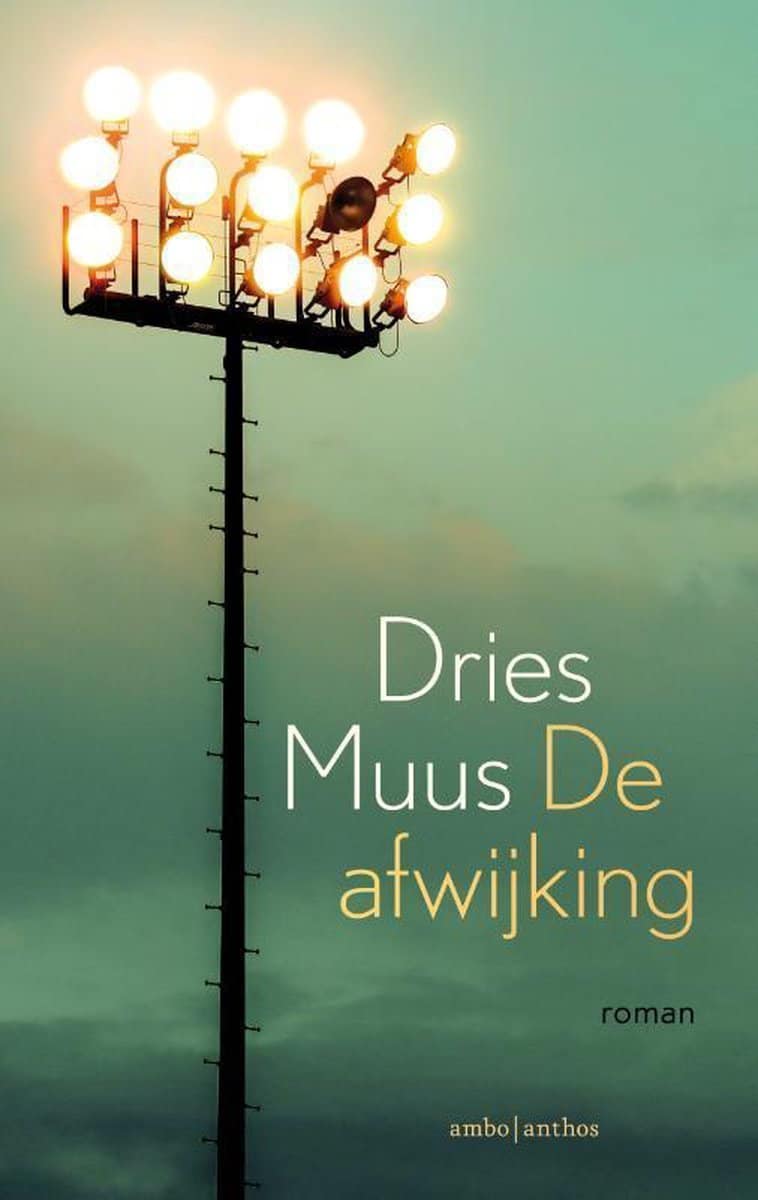

‘De Afwijking’ by Dries Muus: Faustian Drama on and off the Football Pitch

Dries Muus has written De afwijking (The deviation), a beautiful coming-of-age novel against the backdrop of an urban football environment. The structure of his story is very clever.

Literature and sport, apparently a difficult combination. In recent decades, however, increasingly better non-fiction has appeared, about cycling and football in particular, partly thanks to magazines such as De Muur, Bahamontes, Hard Gras and Staantribune. These contain in-depth reports on the culture of sports, often penned by writers with literary ambitions, or journalists wanting to publish longer, well-researched stories, for which there is insufficient room in traditional media outlets.

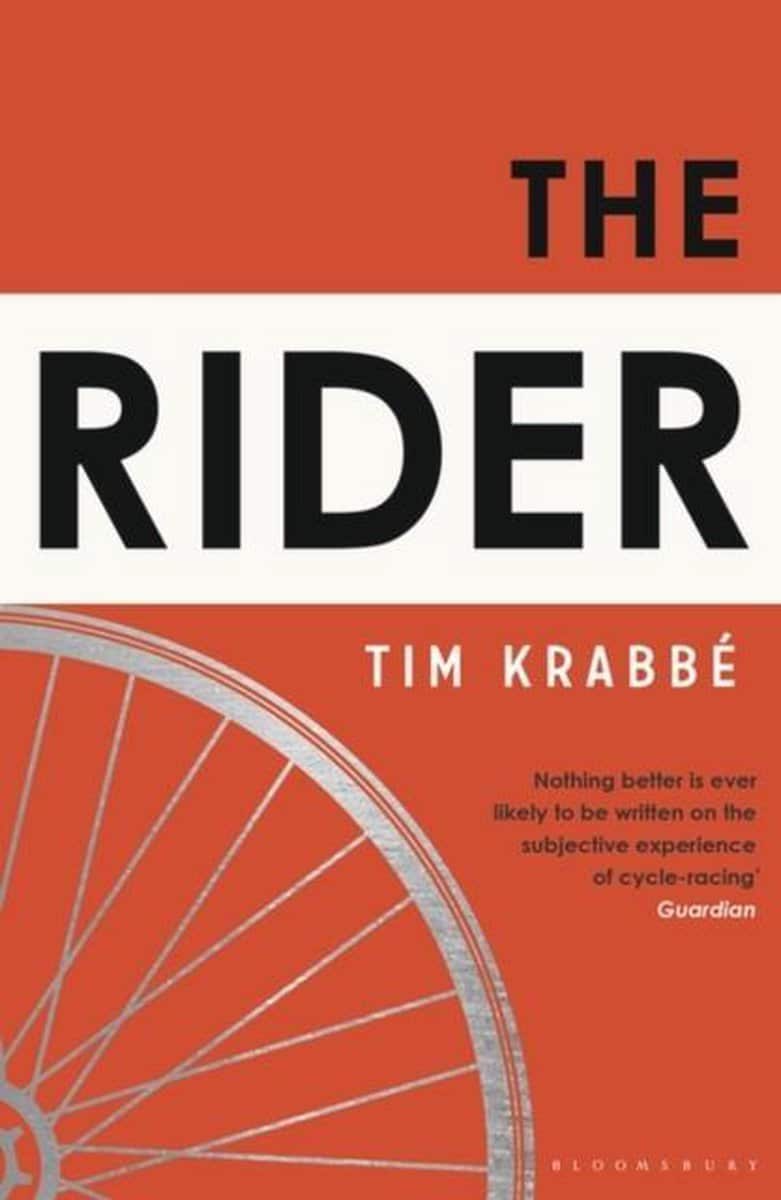

But in literature, especially in Dutch, sport remains on the sidelines. That is slightly strange, because sport lends itself perfectly to drama and to struggle. It is a world of excessive ambition, of boundless joy and deep disappointment. Of course, there is the absolute classic De Renner (The Rider) by Tim Krabbé, who, as a chess player, has a lot of affinity with the emotions and miseries of sport. And more recently there was the wonderful debut Een uur en achttien minuten (An Hour and Eighteen Minutes) by Peter Zantingh, although the football setting there mainly slumbers in the background.

Not so in the debut novel of Zantingh’s contemporary Dries Muus (b. 1983), literary critic at the Amsterdam daily newspaper Het Parool. There are similar themes in each book, but Muus foregrounds football just a little more prominently. It is what the life of Mattias ‘Matty’ Groen is all about. He is a ‘born striker’ as the saying goes, a teenager who will do anything to become a professional player.

Dries Muus

Dries MuusⒸ Ruud Pos

Although the story revolves around Mattias’ coming of age, in this debut novel he is not the only protagonist. In the first scene, the preview, we also meet Albert de Leeuw, coach of the youth team at professional club Achilles. Albert knows that he is past it, that his methods and motivational techniques are a bit outmoded, but when he sees Mattias dribbling, he wants to prepare a golden boy for the first eleven one last time. Then his work will be done. And then there’s Lize, Mattias’s struggling single mother, who does everything she can to understand and support her teenage son.

After his brilliant performance against De Leeuw’s team, Matty signs a contract with the professional club. His dream seems to become reality. Before his first match, he begs the football gods for mercy and help: they can do anything to him in exchange for a chance at professional football. It’s the kind of Faustian deal you sense can’t end well.

Before his first match, he begs the football gods for mercy and help: they can do anything to him in exchange for a chance at professional football

After a challenging start, Mattias is getting better and better. He scores one goal after another, that’s what strikers do. Achilles is in the lead, and the somewhat slender, shy Matty is finally appreciated and even respected by his teammates. It doesn’t matter that he’s a little quiet, a little different, less streetwise than the other guys, football is the big equalizer here. When you win, you have friends.

Until a minor but humiliating incident in the locker room puts an end to that football fairy-tale. Mattias isn’t just shunned by some of his teammates, the rumour about him is spreading like wildfire. At school, visiting other clubs, through playground gossip, social media and insulting chants in the stands, Mattias is reminded of his deviation over and over. It throws him completely. Despite their own troubles, Albert and Lize each try in their own way to get through to the adolescent teenager, who increasingly shuts himself off from the rest of the world, until even football barely means anything to him.

Muus has constructed his story to the design of an exciting football programme: preview, first half, second half, debriefing. In short chapters we are increasingly swept up in the maelstrom of Matty’s thoughts, we see how he slowly but surely drives himself crazy, with good, precise descriptions. This is how a person gets depressed, and how he can drag others down. “The unhappiness is leaking under the door of his room – a gas that is slowly suffocating her,” is how Muus describes the relationship between Mattias and his mother.

Muus’ writing style is not that remarkable, although there are some beautiful sentences and observations in the book. At times, too, his story has something of a young adult novel, but that’s not a bad thing. Because this story is very cleverly constructed, and in the final Muus certainly shows that he knows how to write an exciting scene, and, to throw in a football metaphor, how to wrongfoot the reader. Along the way, we experience the coming of age of a boy, who struggles with himself and with life.

An expert from De Afwijking, as translated by Paul Vincent

The first time it happens, Matty thinks it’s to do with his goals.

Last Saturday he scored a hat-trick against Dignitas. Afterwards his opponents queued up to praise him, their trainer was complimentary too, and an agent actually made a beeline for him. Even before Matty was able to shake his hand, the trainer intervened. He stopped just short of throwing ‘that vulture’ out of the ground. Shortly afterwards Matty heard two club members say that not even Ap de Leeuw could stop this: in a few months that kid would be simply ‘snapped up’ by a foreign club. That’s how it went these days.

So it’s almost logical that Matty should also be talked to about it at school. Well, talked to. Three lads from the second class of pre-vocational secondary education, who were always hanging around in the corridor, leaning on the central heating in padded winter jackets, nudge each other as Matty passes them.

‘That’s him,’ whispers the smallest one. While Matty walks on as nonchalantly as possible, they giggle like nervous fans. It goes as fast as that. Of course this is just the beginning. Some top players are also recognised in the street, complete fan accounts are devoted to them, visiting supporters praise them, chicks offer themselves in the comments with telephone number and all.

Matty resolves to remain level-headed amid all the attention. He’s not going to become one of those top footballers who steps out of the team bus with dead eyes and headphones pounding, ignoring supporters. He’s going to make time for his fans. Actually he has already got off on the wrong foot. The next time he will at least look at them for a moment. With a nod, a simple greeting you can make someone’s day.

The second time it happens, on the way to the canteen, he hears his name from a distance, The odd thing is that the four guys are already talking about him before they see him. As Matty approaches the group they sound more mocking than impressed, like with a teacher who is too soft.

‘Mattyyyy!’ shouts the tallest one. ‘What’s it like in the shower?’

They burst out laughing. In a reflex Matty laughs with them. A hand pushes him, a fist lands against his shoulder, and while the boys go outside jeering, Matty shuffles to the canteen.

What’s it like in the shower? What are they getting at? Can it be something good?