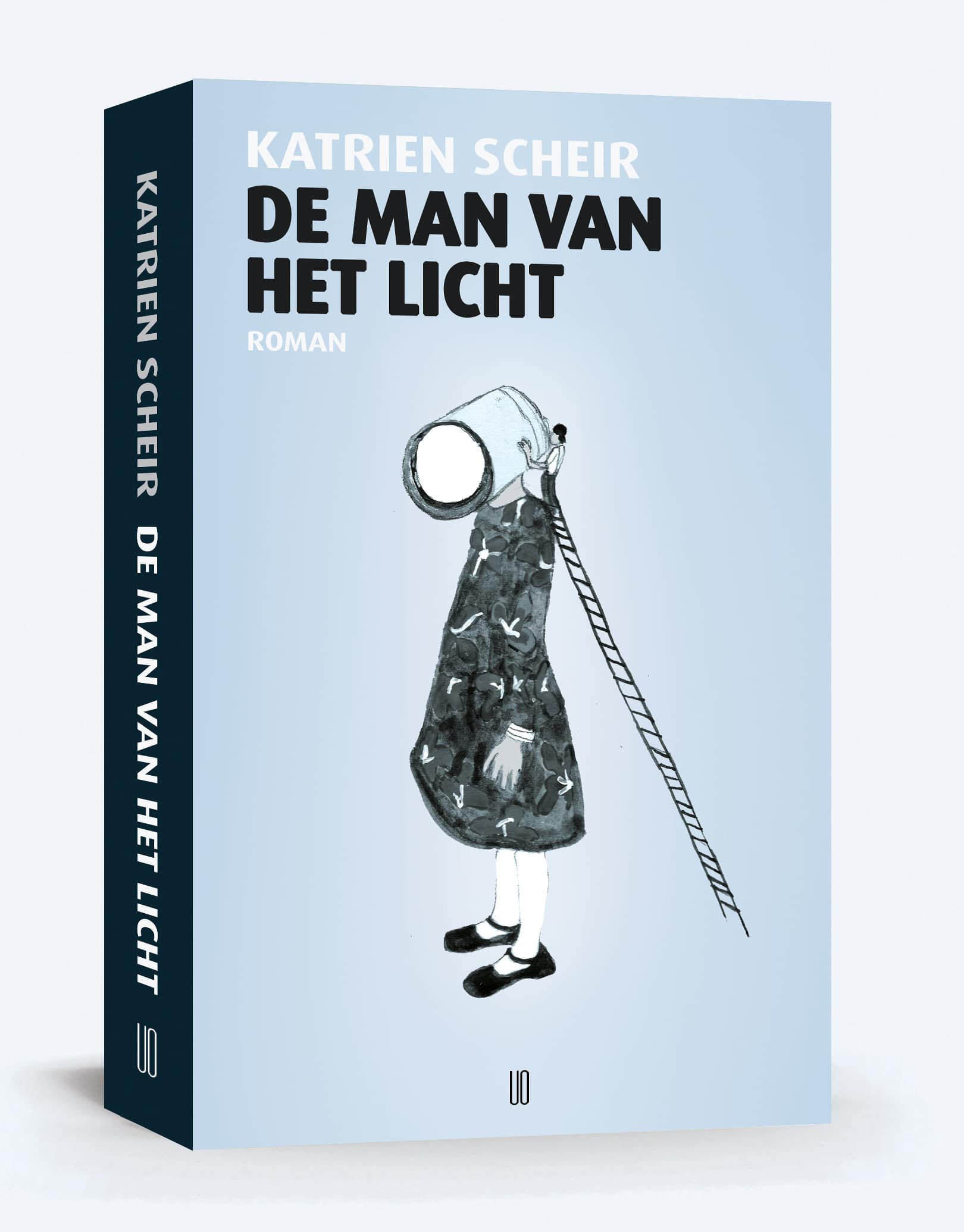

‘De man van het licht’ by Katrien Scheir: Caught in a Sophisticated Trap

Why does a young woman choose to stay loyal to an old man who does not treat her well, to put it mildly? In her debut novel De man van het licht (The Light Man), Katrien Scheir portrays the often very difficult position of women in a #MeToo situation.

De man van het licht (The Light Man) tells the story of the young, ambitious writer Jelena, who, due to her upbringing in institutional care, has never really had the opportunity to develop her talents to their full potential. Drifting from care to foster home, she has had to overcome all kinds of barriers. When she nevertheless manages to go to university to read literature, she is told after a year that because of the state benefits she “enjoys”, she is not allowed to study. She must apply for work and find a job!

Katrien Scheir

Katrien ScheirHer luck seems to be turning after she sends a kind of open letter of application to various cultural establishments across the city. She gets only one reply, but it is from the man known as the Professor, the director of the National Theatre, who is regarded as the cultural conscience of the nation.

Jelena and an old professor, if that rings a bell, of course, you are thinking of Uncle Vanya, the play by Anton Chekhov. Scheir, an experienced playwright who worked with De Zwarte Komedie theatre company in Antwerp for a time, got the idea for her debut novel during a performance of that play.

The Professor sees Jelena’s talent and promises to help launch her career. This takes her from the dismal back room of restaurant Bon Ton to a seat at one of the tables in the exclusive venue itself, where like the rest of the cultural elite she now enjoys the exquisite dishes whose leftovers, only a few weeks earlier, she had washed down the sink. At last, she is successful.

The Professor, sly in his actions and slick with his words, knows exactly how to manipulate her

To concentrate more fully on her writing, the Professor lets her move into the private rooms of the National Theatre. But it soon becomes apparent that a dark shadow hangs over this generous offer from her patron. The Professor, who suffers from a heart condition, needs her love, her admiration and (physical) attention. Like a toddler, he begs her to come into his bed.

Jelena feels like she can’t help but submit to his pleas. She certainly doesn’t want to be ungrateful. She knows what it feels like to be abandoned, how devastating it can be to be abandoned when you need love. The Professor, sly in his actions and slick with his words, knows exactly how to manipulate her, and Jelena realizes much too late what is happening. She feels complicit in something of which she was unaware. At the same time, she does know she has something the Professor desires. She is not hopelessly naive, but the trap into which she has been lured was too sophisticated.

This is a striking illustration of why it is often so difficult for a victim to escape from an abusive situation

Very astute, and in beautiful, gripping scenes, Scheir shows us the flip side of a #MeToo story. This is a striking illustration of why it is often so difficult for a victim to escape from an abusive situation, and how coercive a mixture of psychological and physical pressure can be. Jelena has almost no choice. She must either lovingly “care” for an old, manipulative man who gives her opportunities or return to the damp restaurant kitchen and poky attic room that made her sick and which she can barely afford. What kind of life do you have if those are your options? What can you do when your benefactor threatens to drag dozens of others down with you if you don’t give in to his whims? Who can you confide in when your own institutional care background is problematic and you want to take on a respected member of the cultural elite? When even your old girlfriends think you’re the one taking advantage of that poor Professor.

Scheir, who by her own account hesitated for a long time between writing and painting, shows herself to be a true wordsmith in this debut. She creates beautiful, telling neologisms, such as “sunglasses pimp”, “pickled onion face,” “candy jar eyes,” and “mourning suspenders.” The whole atmosphere of the book is slightly oppressive, like a macabre fairy tale, with a glimpse of hope in places. Sometimes that hope is justified, but more often it is futile. That is how life goes if you haven’t been handed the skills to sail along with the success stories of those who were born fortunate. Because who cares if you yell or whisper, if no one who matters hears you? When hardly anyone sees you as you are?

In the background, there is one person who does see Jelena for who she is, how she is being torn apart, and how she doubts herself and struggles. When she has recovered, he might be able to bring light into her life.

An excerpt from 'De man van het licht', as translated by Paul Vincent

Out of breath, Jelena rang the bell at the future, though she could only just reach it. The colossal building was filled with the pride of receiving emperors with flags and blaring horns. It looked down at Jelena from a stately height. But the masts were like the bare branches of the late autumn and on the front of the building the paint was flaking off here and there. A building dog-eared like a travel diary.

Her case fell over. Upstairs a dog barked. She looked up, feeling slightly dizzy with naïve awe. Heavy clouds drifted past, bumping into the dome-like soft cushions. Dusk was already falling. The barking sounded louder and louder. Balcony doors flew open. An ancient man with wild white hair appeared. He wore a red dressing gown like a royal cloak. Jelena could not see so clearly without her glasses, the future looked hazy to her. In a reedy voice, she said: ‘It’s about the spontaneous application.’ It sounded almost spontaneous.

The Professor replied stiffly and under his breath: ‘Just a moment, we open the doors by hand here.’ Jelena could scarcely understand him, but however soft his voice sounded, his words boomed out. Though he was ancient, he had a powerful presence, something immortal. There on the balcony, a whispering god thundered, there a monarch scratched invisible laws in the sky. Next to him, a brown dog was jumping to and fro, barking loudly. Could she wait a quarter of an hour? Jelena thought she heard, the man pointed to his timepiece. She did have a quarter of an hour for the future. Then the balcony door slammed shut again. She tidied the wet wisps of hair that stuck out from under her hat and curled her toes in her pumps. She waited.

Katrien Scheir, De man van het licht, Uitgeverij Oevers, Zaandam, 2021, 304 pp.