Dear Government, Please Make Use Of Historical Knowledge to Defeat the Pandemic

Those trying to solve the current coronavirus pandemic cannot do so with a purely biomedical and technical strategy. Four Dutch historians make the case for a multidisciplinary approach, taking into account the social, cultural, economic and psychological dimensions of society. History serves as a toolbox in this aim, as we derive lessons and insights from the past which we can still use today to defeat the pandemic.

In the summer of 1849, countless big events all over the Netherlands were cancelled due to an outbreak of cholera. In a great many cities, the annual funfair was not permitted to go ahead, as the chance of spreading the disease was deemed too great. Amsterdam’s entrepreneurs were not content to leave it at that, and they protested, drawing up a petition in which they noted their main objections: in their view, the measures were in conflict with the law and the result of bad political strategy. Now that they had no turnover, they were threatened with mass bankruptcies. They also believed that the people were suffering, as they needed these kinds of festivals to remain ‘in good humour’.

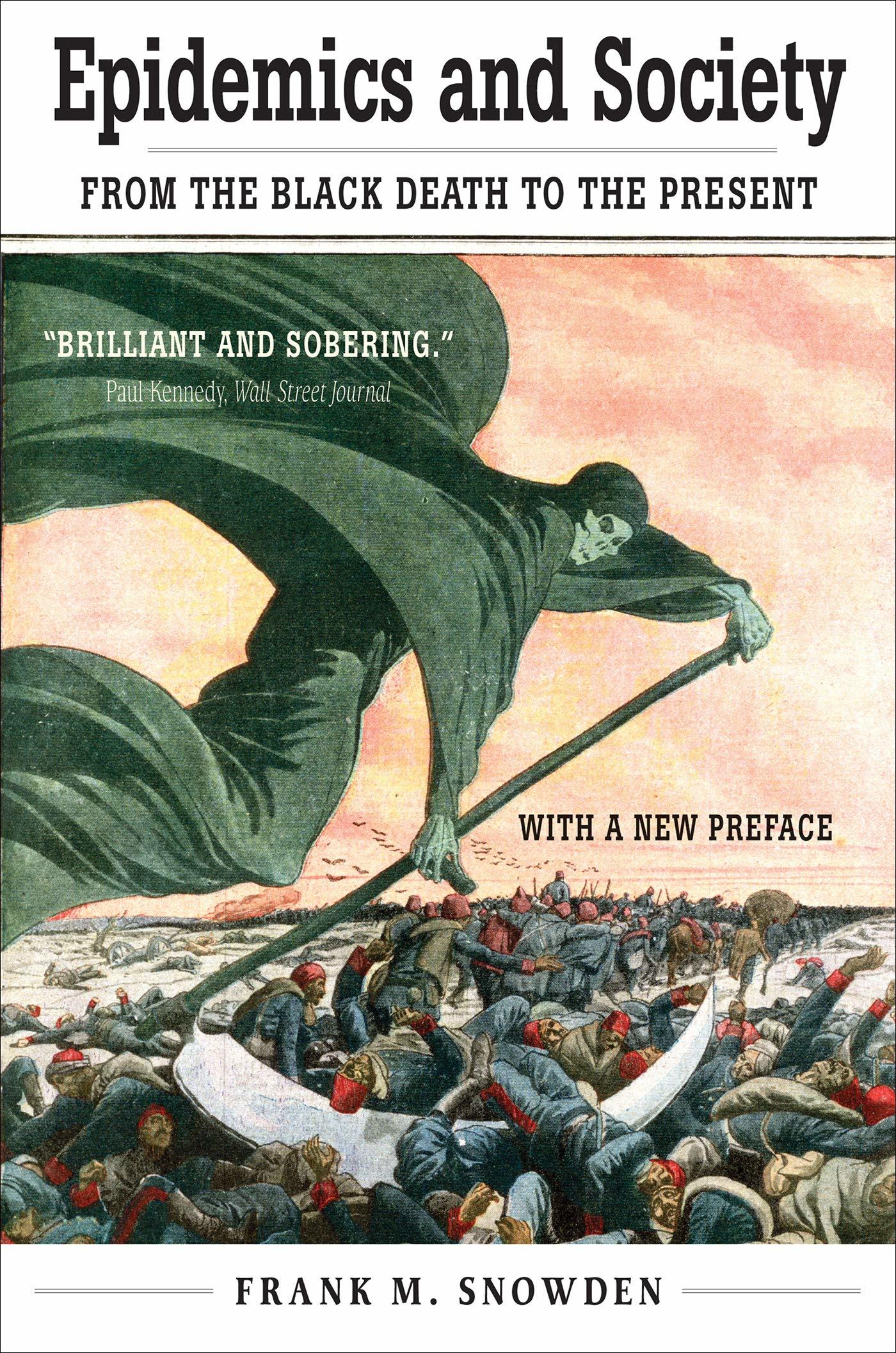

Lithograph on the occasion of the cancellation of the funfair in Amsterdam, 1849

Lithograph on the occasion of the cancellation of the funfair in Amsterdam, 1849© Atlas van Stolk

The Amsterdam entrepreneurs’ appeal dates back to 1849 but their arguments are all too familiar today. The longer the coronavirus pandemic and the restrictive measures last, the more interest groups make their voices heard. Just take a look at the Dutch website petities.nl, where anyone can start their own petition. From owners of hospitality businesses, gyms and museums to yoga instructors, university students and music schools: many sectors have since started a petition in which they demand a relaxation of the measures.

What began as a medical crisis has now expanded to become a social and political crisis of unprecedented proportions

The situation is clear: what began as a medical crisis has now expanded to become a social and political crisis of unprecedented proportions. As we previously

argued in NRC Handelsblad, navigating our way out of this crisis requires a broad, multidisciplinary approach. This is what is known as a ‘wicked problem’, one in which the solution becomes part of the problem. In this case, the short-term saving of lives (by applying harsh measures) leads not only to financial malaise for large sectors of society, but also to a disproportionate sacrifice of healthy years in the longer term.

The closure of gyms, for instance, leads to inactivity and overweight, while the closure of education results in loneliness and suicidal thoughts among students and young people. Besides the insights of virologists, we therefore also need knowledge from other disciplines, such as economics, psychology and cultural studies, to emerge from the crisis in a balanced fashion. That is all the more important, as we are dealing with a ‘slow-onset disaster’, a silent killer. It also means that after applying the medical miracle, the vaccine, the crisis will not magically be over, as the social consequences will be perceptible for a long time to come.

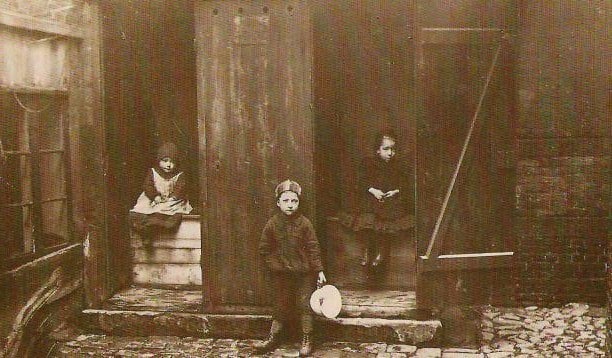

Vaccination during a smallpox epidemic in Maastricht in 1927.

Vaccination during a smallpox epidemic in Maastricht in 1927.© Spaarnestad Photo

Without wishing to dismiss any part of the contribution of medical and other specialisms, we argue for better use of historical knowledge in the collective battle against today’s coronavirus crisis. Historians, after all, have deep knowledge of societies and epidemics. The past is effectively an accessible reservoir of knowledge and experience that can be instructive for the future. Of course, every crisis is bound by its culture and its era, but recurring patterns can be discerned, from which we can distil a few valuable insights. We mention four here.

Firstly, history shows that epidemic diseases cannot be described from a purely medical perspective, but that they are uniquely social occurrences. The way in which people react to diseases, the political and social interventions, the reporting in the media and the search for moral and social causes for outbreaks are socially, culturally and historically determined.

New infectious diseases are systematically coupled with thinking in terms of scapegoats, political unrest and social reform movements

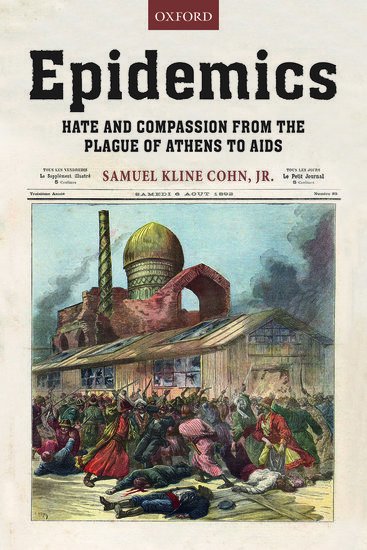

This point is clear from two impressive works offering an overview of the subject: Epidemics. Hate and compassion from the plague of Athens to AIDS (2018) by Samuel Cohn and Epidemics and Society. From the Black Death to the Present by Frank Snowden. Both authors point to the need to place epidemics in a broader social and historical context and not to view them as purely medical problems. New infectious diseases, for example, are systematically coupled with thinking in terms of scapegoats, political unrest and social reform movements. In view of these social dimensions, Richard Horton, editor-in-chief of The Lancet claims that Covid-19 should not be termed a pandemic but a syndemic, emphasising the fact that a pandemic is not exclusively a medical issue, but that it is also embedded in a broader social and ecological context.

Secondly, historical research shows that pandemics remarkably often follow the same course. In a 1989 article the historian Charles E. Rosenberg compared the course of an epidemic with a play in four acts. At first just a handful of suspicious cases crop up, but as the disease spreads faster, social unrest grows. Besides going in search of medical and social explanations, people also assign scapegoats who are presumed to have causes the crisis. The unrest then culminates in a crisis, which is also political in character. Invariably riots and protests break out, as forms of social discontent or inequality come to the surface. A known example is the cholera riots in Hamburg in 1892. Residents of deprived areas were furious because the city authorities had neglected to better organise the city water supply.

The communal toilets without connection to the sewage system facilitated the spread of cholera in Hamburg in 1892.

The communal toilets without connection to the sewage system facilitated the spread of cholera in Hamburg in 1892.© Chronik Hamburg, Wikimedia Commons

Thirdly, an epidemic is extinguished gradually. In Rosenberg’s words, ‘Epidemics ordinarily end with a whimper, not a bang.’ He is referring to the famous poem The Hollow Men (1925) by T.S. Eliot. With his verses, the American-British poet expressed the collective emotions of futility and depression with which many soldiers and civilians struggled after World War I. To sum it up: an epidemic might end from a medical perspective, but the psychological and social disruption leaves deeper marks. Interestingly the Dutch Association of Mayors recently drew up a letter commenting on the question of how mayors can take the lead in dealing with bereavement in this extraordinary time. The Association points out the great importance of collective mourning – particularly now that many people have had to say goodbye to their nearest and dearest differently from normal.

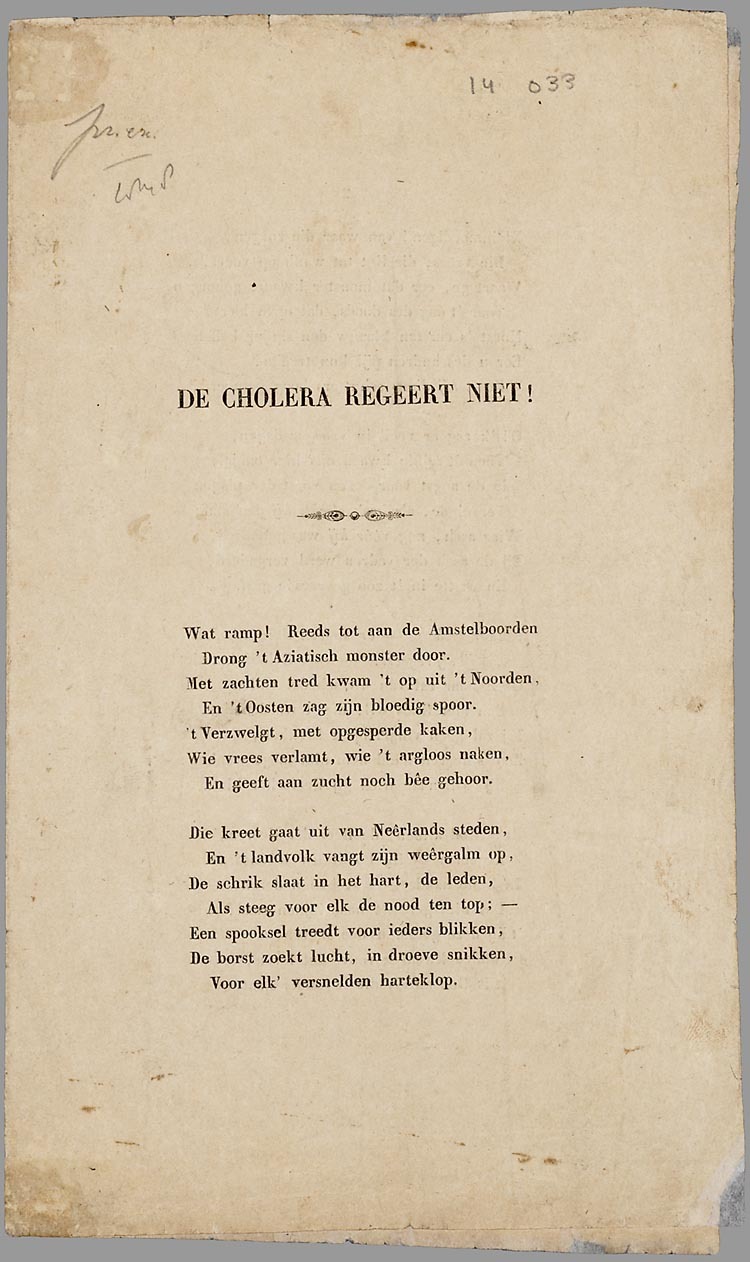

For that very reason, it is important throughout the crisis – and that is the third insight – to pay attention to the issue of a sense of purpose and mental resilience. The past reveals countless rituals to give meaning and coping mechanisms, which are also relevant for dealing with the current crisis. We single out one of them here, namely the cultural forms of resilience. Historical research shows that cultural media (stories, songs, sermons, processions, pictures and charity concerts) had many functions. They not only offered an outlet for emotions such as fear and uncertainty but also provided comfort and meaning because they connected people. In particular, the disaster song genre fulfilled this role: singing and mourning together offered comfort and hope.

Disaster songs about cholera, Amsterdam, 1848

Disaster songs about cholera, Amsterdam, 1848© Meertens Institute, Amsterdam

Authors and artists also encouraged a sense of community: they aimed to increase solidarity among citizens by heightening empathy with victims and organising acts of charity. They focused on the question of how the community could come through it as a whole. During the various cholera epidemics (and other catastrophes) an impressive number of citizens’ actions took place, targeting general recovery. The local newspapers also encouraged people to help one another. A wide variety of actions was organised. For instance, in 1849 a race in the seaside town of Zandvoort raised 300 guilders for those in need there. During a charity concert in Rotterdam, 250 people performed to help the community.

Culture is indispensable for increasing psychological and social resilience

It is precisely from this that we can draw an important lesson for the current crisis: culture is indispensable for increasing psychological and social resilience. Stories, poems, music, theatre and other art forms offer a medium in which people can escape, reflect and mobilise. For that very reason it is also important in times of crisis to continue to invest in culture in the broadest sense of the word.

A fourth and final historical insight is that humanity will always have to deal with new infectious diseases, that risks can never be 100% offset and that we will have to learn to live with the idea that every human being is mortal. Governments currently like to talk about exit-strategies, as if there were a clear, straight line out of the crisis. They make use of ‘dashboards’ showing at what ‘R number’ or reproduction number cinemas and theatres can reopen. Such infographics seem to appeal to our modern urge for control, but more importantly, they suggest that interventions are determined purely by biomedical data.

We will have to learn to live with the idea that every human being is mortal

This mechanism is also expressed in the ‘toolbox’ on which Dutch politicians greedily draw to bring the virus under control. It must first be dealt a blow with a hammer, after which society must learn to dance with it. The ministers derive this imagery from the engineer and publicist Tomas Pueyo, who published the very influential article ‘The Hammer and the Dance’ in March 2020. In it he introduces a series of ‘basic dance steps’ which governments should follow to navigate the crisis as efficiently as possible. Among those dance steps he counts matters such as social distancing, contact tracing, hygiene education and banning large events. Pueyo presents a technocratic, top-down approach in which interventions are purely biomedical in character.

If we can learn something from the past, then it is that such a top-down, biomedical approach does not sufficiently do justice to the complexity of the current crisis. It would be far better to speak of adaptive strategies. Of course the vaccine will help us, but in order to find the right exit strategy it is also essential that we pay attention to social, economic, psychological and cultural dimensions of societies. We therefore argue for the development of an alternative choreography, in which social and cultural coping mechanisms also play a role. History can function as a toolbox in that process.