‘Dear Politicians, Reading Must Be Given Top Priority’

In the Netherlands, schools, libraries and institutes are doing their utmost to get people to read. But according to Henk Pröpper, writing recently in the Volkskrant, this is nowhere near enough. ‘Our politicians need to wake up to the fact that low levels of literacy and book reading have an adverse effect on the economy’.

The past year has seen an avalanche of reports on the problem of functional illiteracy and the decline in reading in the Netherlands. What do they show? More than in nearly every other western country, the young and to an increasing degree older people too, lack the motivation to read. The Culture Council, the School Inspectorate, and even the Social-Economic Council have all called for a reading offensive. The gulf between the highly literate and the functionally illiterate is growing and with it the gulf between people who do and those who do not have access to essential information and knowledge. An obsession with smartphones and Netflix has killed conversation in many families and prevents parents from reading to their children.

Reading is often experienced as a duty, rather than as an opportunity or enrichment. Every report warns that in the long run this problem will have serious economic and political consequences. It is not only because competent readers who understand what they read generally exhibit more empathy, are more successful in distinguishing true from false, live happier lives and on average live longer and healthier lives than non-readers. What should be a wake-up call for the politicians in The Hague is that functional illiteracy and a reluctance to read have seriously damaging economic consequences.

19th-century skills

One of the goals of the Dutch government is for this country to become a world-leading knowledge economy. Yet there are more than two million functionally illiterate people in the Netherlands, a handicap that is often passed on from generation to generation. In respect of the labour market, one hears nowadays about the need for ‘21st-century skills’, which all sounds very professional when in many cases people are still struggling with the ‘19th-century skills’ of reading and writing. Nevertheless, even the oak moth problem caused more political and media concern this year than the painful recognition in all these reports that the country faces a genuine reading problem.

Despite the efforts of hundreds of thousands of teachers, lecturers, librarians, volunteer readers in schools, nurseries and hospitals, mothers and fathers, the international ranking of Dutch school children in reading skills and reading pleasure is declining. Possibly such rankings are not entirely relevant. More important is what we are denying children and adults when they do not have access to what was once called the world of imagination: the formidable power of language and books to set one thinking, to stand in someone else’s shoes, to discover other worlds or a different perspective, and to give one a sense of living a full life. And by means of all that to become a fully-fledged citizen, an involved participant in our society, better armed against fake news and extreme ideas and ideologies.

Functional illiteracy and a reluctance to read have seriously damaging economic consequences

Long ago in primary school I was fascinated by the European voyages of discovery. In the school library I found (romanticised) ship’s journals which set me dreaming and awakened in me an enormous lust for life. Whoever has stood on the Cape of Good Hope where two oceans meet – a magical picture – can imagine something of the hopes and fears of seafarers rounding similar headlands on the way to … where? Not having the faintest idea of what to expect or what wonders or monsters might be lying in wait, made reading those books an unforgettable experience. It was both wonderful and terrifying for me to identify with some cabin boy for whom literally everything was new. From that moment on, reading became for me an exploration of the unknown, and has remained so ever since.

As a child I was inspired by those cabin boys and deckhands, bright lads often from poor families, who distinguished themselves by being themselves and showing ambition: on occasion by learning to read. Later on, other figures on board attracted my attention. In Dutch books, apart from the captain, they were usually traders and pastors, but book-keeping and accounting always seemed to me to be more important activities than the baptism of ‘natives’ by the man of the Word, the man with the Bible. Figures before words, with words being at best a lowly instrument in the service of trade. To this day the Dutch vision of politics and economics still proudly reflects this view

I was reminded of this on reading Civilizations, a new novel by the French writer Laurent Binet (author of HHhH) in which he turns western perceptions of the world upside down. He imagines the world of Charles V (in around 1530) being colonised by the Incas who are amazed by the violent politics and religious conflicts that they encounter in this, to them, unknown continent. They are most intrigued by those whom they call the ‘tonsured’. They are mainly fanatical and far from trustworthy men with shaven crowns who believe themselves to be responsible for three tasks: glorifying their god; harvesting the dark drink that tastes so good (wine), and guarding and maintaining ‘the leaves that speak’. This last is considered the most important since all secrets, earthly and religious, lie hidden in those leaves.

The Incas, therefore, busy themselves with learning how to read. The narrative of their discovery of a ‘New World’ is one of taking refuge in knowledge, not in territory, not in riches, not in power. Binet’s novel is an anti-history which shows how different the history of Europe could have been. It also shows that ‘developed’ and ‘undeveloped’ are treacherous concepts. They depend on what you do with your development and your potential, and what your ambitions are. That should make us all stop and think.

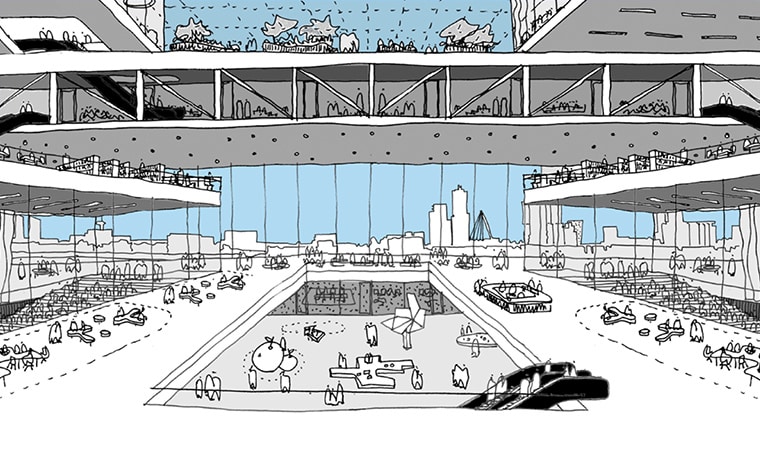

Visual of the future Culture Campus in Rotterdam

Visual of the future Culture Campus in RotterdamCulture Campus

Some time ago, the Volkskrant

reported on a scheme to build an iconic centre in Rotterdam South. This neglected district would seemingly benefit greatly from the construction of a ‘Culture Campus’, an eye-catching building which would bring together knowledge, culture and tourism. At least, that was the idea. The reaction of Wim Pijbes, former director of the Rijksmuseum and now the director of the Droom en Daad (Dream and Action) Foundation was interesting. For whom, he wondered, was it actually intended? The residents of the district, or visitors, tourists and students? And what should such a Centre be if one really wanted to help the local residents? Then, after referring to exceptional libraries designed by Dutch architects in Tianjin (Winy Maas), Doha and Seattle (Rem Koolhaas) and Birmingham (Francine Houben) he concludes with the solemn admonition: ‘In Rotterdam South, start with reading and writing, with language.’

That sentence is itself memorable, for it goes to the heart of the problem. Constructing impressive buildings is one thing; but how can you make sure that the people living around it will actually benefit? An iconic building must be imprinted in people’s minds; formed by language, it becomes a story, a narrative. It tells us that we belong, that we have a role, that we have reason to be proud, a reason to make a start and to seek adventure. Entering a great library is just such an adventure, which becomes more exciting with every book we touch.

With all our 21st-century skills, we still do not understand how much gold is to be discovered in reading

Our narrative must begin at the beginning, with reading to young children, with creating school libraries, with motivating young and old to read, to learn and to enjoy, and thereby to feel that they belong. Schools, libraries and organisations such as the Dutch Reading Foundation, the Reading and Writing Foundation, the Literature & Children’s Books Museum and the CPNB (a foundation that campaigns for wider reading in the Netherlands), do everything in their power to involve people in reading. Programmes like The Art of Reading, Taking Part through Language and The School Library are also successful. However, much more direction is needed to turn the tide and win whole-hearted support from politicians in The Hague for our language and for reading. Education and Culture, two of the three wings of the Ministry of Education, Culture & Science, should make it a point of honour to make reading, with intelligent and emotional understanding, their joint ‘mission’. This is not a crusade against counting but against the bean-counters, because they count wrongly. With all our 21st-century skills, we still do not understand how much gold is to be discovered in reading. It is time that we again bend our heads over the ‘leaves that speak’ and ensure that everyone is given the chance to do it.

Facts & figures

On the Reading Foundation’s website, Leesmonitor.nl, one can find data, facts and interesting material on the development of reading and reading behaviour in the Netherlands. The site draws on scientific research, provides insights and makes suggestions. What exactly is the motivation to read? What conditions motivate reading? Why are we reading fewer books? Are there differences between boys and girls? What is important about free reading or being read to? What changes in reading habits are brought about by computers and digitisation? Has there really been a decline in reading or are people simply reading differently? What effect does this have on comprehension? The website discusses existing programmes aimed at helping people to read and also shows why there are some reasons for optimism. For instance, many parents have a positive attitude towards reading, while the pleasure and usefulness of being read to are widely recognised.

+ The number of keen readers is declining, and therefore so is the overall time spent reading.

+ The reading time of those aged between 13 and 34 declined by a quarter between 2013 and 2018. Young people aged between 13 and 19 read the least: 10 minutes a day.

+ Older people, especially those over 65, read the most: up to 1½ hours a day. A generation gap appears to be emerging.

+ Since 2013, men are reading significantly less, while the reading time of women is stable.

+ Membership of libraries has declined steadily since it peaked in 1994, from 4.59 million (30% of the population) to 3.71 million (22%) in 2017, Since then the number of members has remained fairly stable.

+ The lending of printed books has more than halved since 2000, from 174 million books to 67.3 million in 2017. The decline involves adults in particular. More books are now lent to children than to adults.

+ The reading skills of Dutch children are still above average internationally. But the Netherlands is being overtaken by an increasing number of countries. Two out of ten 15-year-olds are functionally illiterate; slightly over one in ten are highly literate.

+ The Netherlands (and Belgium) are one of the few countries in which reading skills have declined in recent years. The gulf between good readers and poor readers is growing.

+ In PISA, an international assessment of the reading skills of 15-year-olds, the Netherlands is 15th out of 71 countries. The Dutch government wants to achieve a position in the top 5.