Dionysus on the River Scheldt: ‘Wild Woman’ by Jeroen Olyslaegers

In his second historical fiction novel, Jeroen Olyslaegers brings to life the city of Antwerp before, during and after 1566, the year of the Iconoclastic Fury. His lyrical and at once vernacular language provides a rich story about friendship, solidarity, faith and betrayal.

Jeroen Olyslaegers’ multi-award-winning novel Will

(2016), set in German-occupied Antwerp during the Second World War, demonstrated that he could successfully turn his hand to the somewhat outdated genre of the historical novel. After more than four years of intense work, Wild Woman sends his readers even further back in time.

Jeroen Olyslaegers

Jeroen Olyslaegers© Stephan Vanfleteren

In 1577, a sympathetic innkeeper called Beer, by now in his fifties, looks back from Amsterdam on the events that led him to flee Antwerp ten years earlier. At that time, the city on the river Scheldt was not only a bustling trade hub and a bubbling melting pot of religions, it was also the beating heart of fine art, dramatic societies, cartography and printing.

Beer the innkeeper has lost three wives to childbirth, but before she dies, his third wife bears him a son called Ward. Ward is abnormally hairy from birth and makes it seem as if Beer’s wife did not “mate” with him, but rather with a “wild animal”. In his son’s hairiness, Beer sees both “a hint from Thou up there” as well as a sign of “Thy true ferocity”. It is inevitable that Ward is destined for “something special”.

With his busy inn as a lookout post, Beer is an eyewitness with a front-row seat, as he watches the unrest in Antwerp grow. Regular and welcome customers include the cartographer Abraham Ortelius, the printer Willem Silvius and in their wake even the painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder, nicknamed “Pierre the Turd”, who in no time at all creates an impressive mural with a sleeping Beer surrounded by monkeys.

A failed trade expedition, which attempted to travel to “the Indies” via the North Pole to try and speed up the journey, returns with an amazing loot – two “Skrælings”, an Eskimo woman with her daughter, or “human animals” as Beer calls them. Ortelius receives the “wild woman” as a gift, but entrusts her to Beer’s good care. Although they cannot communicate with each other, Beer becomes more and more captivated by the fourth woman in his life.

Olyslaegers competently portrays historical events in a particularly credible and lively way with just a few choice strokes of the brush

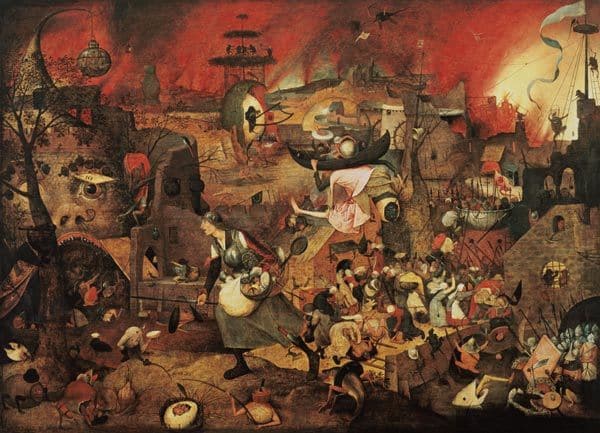

Beer is a member of a wild man’s union, together with three friends: the bookseller Hugo, the blind traveller (and cook) Jeroom, and De Schrale, a grumpy goofball who was apparently the model for Bruegel’s painting Mad Meg. This colourful quartet takes to the streets during the Candlemas carnival; Beer dressed in “bear suit,” with a big “ropey fake beard” and “an ivy crown,” the other three dressed as a king, a hunter, and a wife, pretending to chase the wild man out of town, “to welcome the coming thaw and spring”.

The people of Antwerp look down with disdain on this rabble of dressed-up friends, a city now focused on trade and the idea of progress, “in the eyes of the merchants this animalistic man was a laughable memory of times long gone”. But for Beer, playing the wild man is “sacred” and “the truest form of us all and the ancient past that linked us together”.

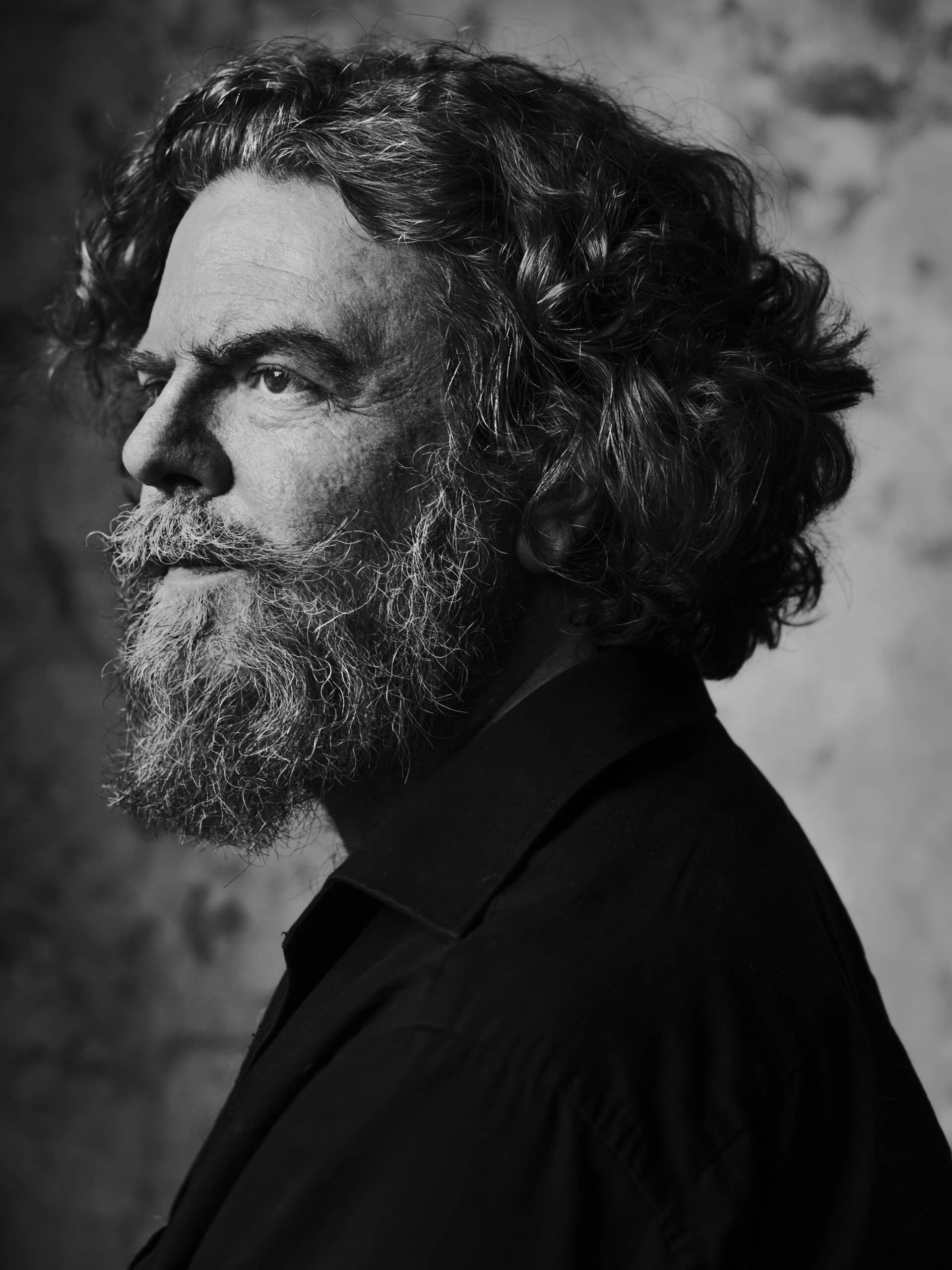

Coat of arms of the city of Antwerp with a wild woman and a wild man

Coat of arms of the city of Antwerp with a wild woman and a wild manHe sees the foreign woman thrown into his lap as a divine answer to his call for love: united, they unmistakably form a reflection of the wild couple that flank the Antwerp coat of arms.

Beer’s testimony is a confession, just like that of Wilfried Wils in Will, with the difference that the innkeeper does not look back at diary entries, but instead addresses his frank confessions directly to God and the reader. Haunted by death, he feels cursed and compares himself repeatedly with the Biblical figure Job.

In Amsterdam, Beer wants to come to terms with his past and undo that curse. His story is a mesmerizing voice-over, which manages to captivate, thanks in part to the imaginative and energetic descriptions. Olyslaegers is a real master of atmospheric creation and competently portrays historical events in a particularly credible and lively way with just a few choice strokes of the brush.

For example, his descriptions of the Iconoclastic Fury, the 1561 ‘landjuweel’ (the ‘Jewel of the Land’ was a large competition of 13 chambers of rhetoric for which an estimated 5,000 participants from twelve different cities travelled to Antwerp), and the first Hedge Sermons (sermons held in open fields in the early days of the Reformation due to the repression of Calvinist religious practice) are grandiose. So too are his descriptions of the Big Beggar’s (Henry, Lord of Bréderode) speech, or of Hugo, who stood with his book stand on the frozen river Scheldt during the harsh winter of 1564.

Lucas van Valckenborch, View of Antwerp with Frozen Scheldt, c. 1589-1593

Lucas van Valckenborch, View of Antwerp with Frozen Scheldt, c. 1589-1593© Städel Museum, Frankfurt-am-Main

In his inn, Beer turns a blind eye to the gatherings of the Family of Love – a secret society that mainly consists of “wealthy people”. Beer, however, never becomes a full member of this masonic gang, even though they force him to assist some of their important members, including the occultist John Dee who writes a satanic book whilst he is a guest with Beer, and the seedy Hungarian Sambucus, who builds a library of forbidden books in Beer’s basement.

Unclear agreements with these rogues ultimately cost the unfortunate innkeeper dearly. His friends see him as a traitor and in August 1567 he is forced to flee to Amsterdam, together with the wild woman and her daughter.

By opting once again to write a historical novel, Olyslaegers chooses to conform to a tradition, but not without transcending the limitations of the genre. A huge research process preceded the writing, mostly done by Olyslaegers’ “brother from another mother” Stef Franck. This research was brought together on the kind of website for which the word ‘surfing’ was coined.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Mad Meg, 1563, Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Mad Meg, 1563, Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp© KIK IRPA Brussels

Bruegel’s Mad Meg – which also occasionally haunts Wilfried Wils in Will – served as a catalyst for the book, but when Franck found a Bruegel-based depiction of a wild man and later an anonymous engraving of a female version with a child, this, of course, proved grist to Olyslaegers’ mill.

Skillfully, Olyslaegers allows fact and fiction to flow into each other, without allowing the documentary element to dominate and maintaining a nice balance between historical and fictional characters. He never falls into the trap of the pedant, but remains, like the wild men who drink “berserker’s blood” before they take to the streets, a fervent follower of Dionysus – letting the imagination run wild.

This wouldn’t be an Olyslaegers book without presenting a committed point of view

The spontaneity, both in the dialogue and in the many flesh-and-blood characters, gives Wild Woman the grandeur of a courtly chronicle. The use of forgotten Flemish words such as “moosmeier” (the medieval job title akin to the binman of today), “vliegmare” (a type of rumour or piece of news, of which the validity is not checked) or “zinkroer” (an old name for a pistol), are never out of place. And when a regular punter – as was apparently the custom – urinates in Beer’s burning fireplace, it is both amusing and enlightening.

But this wouldn’t be an Olyslaegers book without presenting a committed point of view. Beer is throwing stones while living in a glasshouse. He is an accomplice and flees not only because of the turbulence that awaits Antwerp, but also out of shame for his betrayal – of his friends as well as the wild woman. He constantly apologises for his guilt during his confessions, which lowers him to a master of self-deception, to reference Wils from Olyslaegers’ previous novel once again.

When his son Ward asks Beer why the members of the Family don’t want to share their secrets, he answers that connection is “a beautiful thing”, but that at their core, people have “a great need” to be cheated. With this in mind, one of the book’s mottos is particularly well-chosen: Mundus vult decipi or “the world wants to be deceived”, attributed to the German humanist Sebastian Franck.

Beer adds later that deception is always self-deception and that he fled Antwerp because “Antwerpians themselves had already destroyed the unity, even before the Spaniards raped it like avenging angels” – an unmistakable reference to the polarization in our society today.

If Olyslaegers had achieved a “Great Flemish Novel” with Will, then he has managed to outdo and reinvent himself with Wild Woman.

Jeroen Olyslaegers,

Wildevrouw, De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam, 2020, 416 pages.