Diving Into the Past to Improve the Future: Postcolonial Themes in Belgian Art

More and more artists want to cast a critical perspective upon the colonial past in order to influence ongoing debates in our society. Who have been the most notable Belgian artists to incorporate postcolonialism in their oeuvre? An overview, from Marcel Broodthaers to Otobong Nkanga.

There are diverse interpretations of postcolonial art. The defining characteristic, however, is art that takes a critical approach to the colonial past. This is also how postcolonialism is defined in the humanities: it is critical, and sets itself in opposition to the vestiges of Western colonial discourse. Like the Roman god Janus with his two heads, postcolonial art is both rooted in the past while simultaneously fixing its gaze on the future. By critiquing colonial practices from the past such as structural oppression, racism, violence, and economic inequality, these works of art expose contemporary abuses and injustices that are ongoing.

This article is about Belgian postcolonial artists, as the term is defined by Phillip van den Bossche (the former director of Mu.ZEE in Oostende): artists who both live and work in Belgium, not just artists who hold a Belgian passport.

Trailblazers

Clear postcolonial influences have been found in Belgian art since the beginning of the 21st century, but postcolonialism had already been explored by several pioneering Belgian artists. Marcel Broodthaers first allowed criticism of the colonies to shine through his work around forty years ago with Le Problème noir en Belgique (1963-1964). In this painting, his motif of otherwise humorously intended eggs are painted pitch black and pasted to a newspaper article titled “Il faut sauver le Congo”. In doing so, Broodthaers reflected upon the colonial history of his own motherland, which he had previously referenced using more hackneyed tropes like mussels or the national flag. With this work, he demonstrated his status as a true avant-gardist.

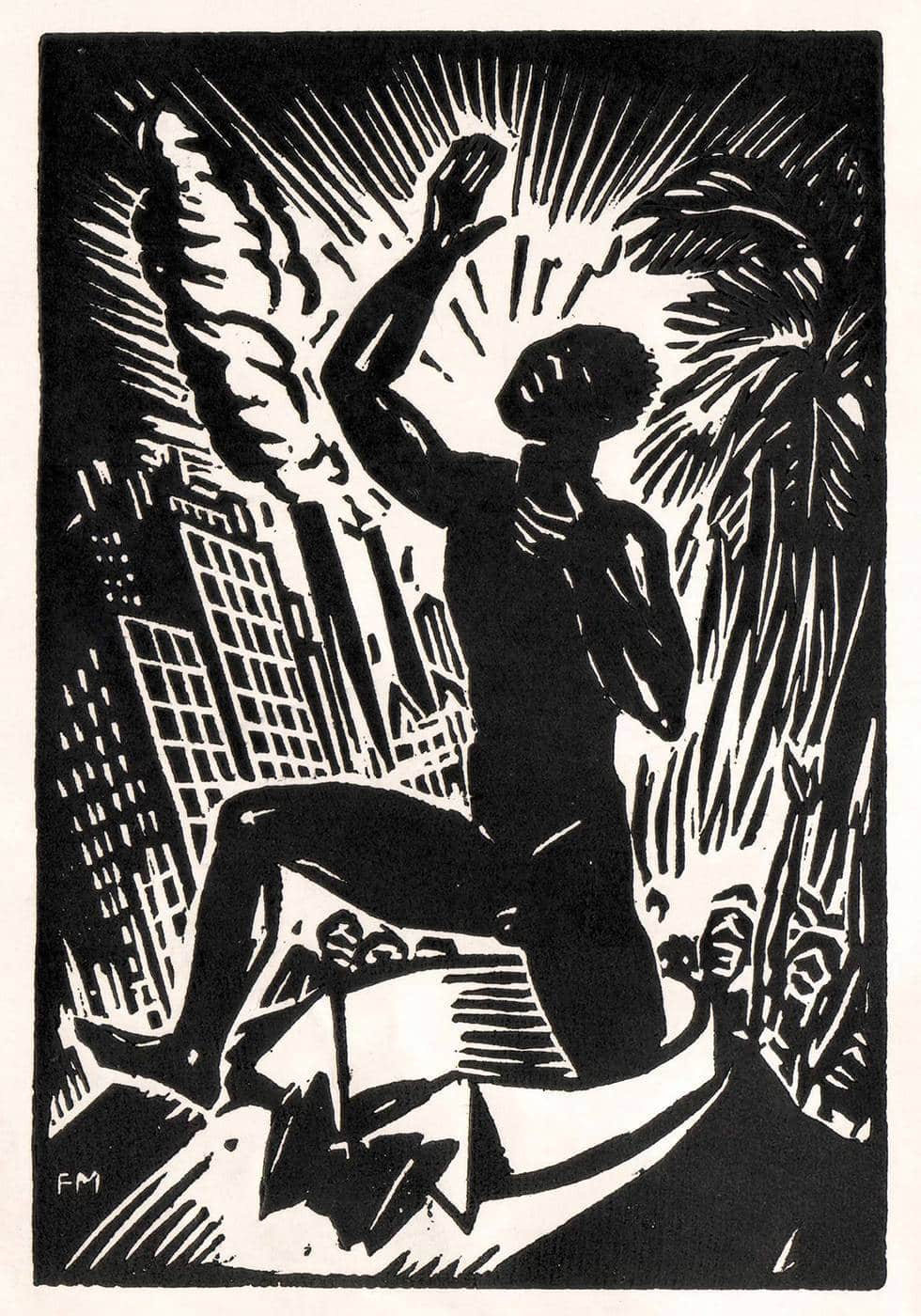

Frans Masereel: Pigments

Frans Masereel: Pigments© Sabam Belgium 2020

Frans Masereel drew inspiration from society for his drawings and paintings. As early as 1937, he crafted a woodcut for a collection of poetry by Léon Gontron Damas entitled Pigments. Two years after its publication, the book was censored by French authorities because it had caused “unrest” in the Ivory Coast. Pigments was a very early example of artistic engagement with the anticolonial emancipation movement, long before there was any talk of decolonization or postcolonialism. In his subsequent work Libération from 1961, Masereel once again made reference to Congolese independence: three naked, black figures celebrate as they saunter away from a stark apartment building – a white businessman watches on in horror.

Venice

At the 2001 Venice Biennale, Mwana Kitoko by Luc Tuymans anchored the tradition of Belgian postcolonial art. This exhibition, curated by the Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (S.M.A.K.) in Ghent together with Jan Hoet, dove into Belgium’s colonial past. Luc Tuymans’ approach was much like that of the Flemish journalist Louis De Lentdecker, whose Wâpi Kongo? offered a critical report following Congolese independence. Wâpi Kongo? brought about a new and unfavorable perspective upon Belgium’s ongoing role in its former colony. Like De Lentdecker, Luc Tuymans condemned the events of the past. But also went on to draw a direct connection between then and now.

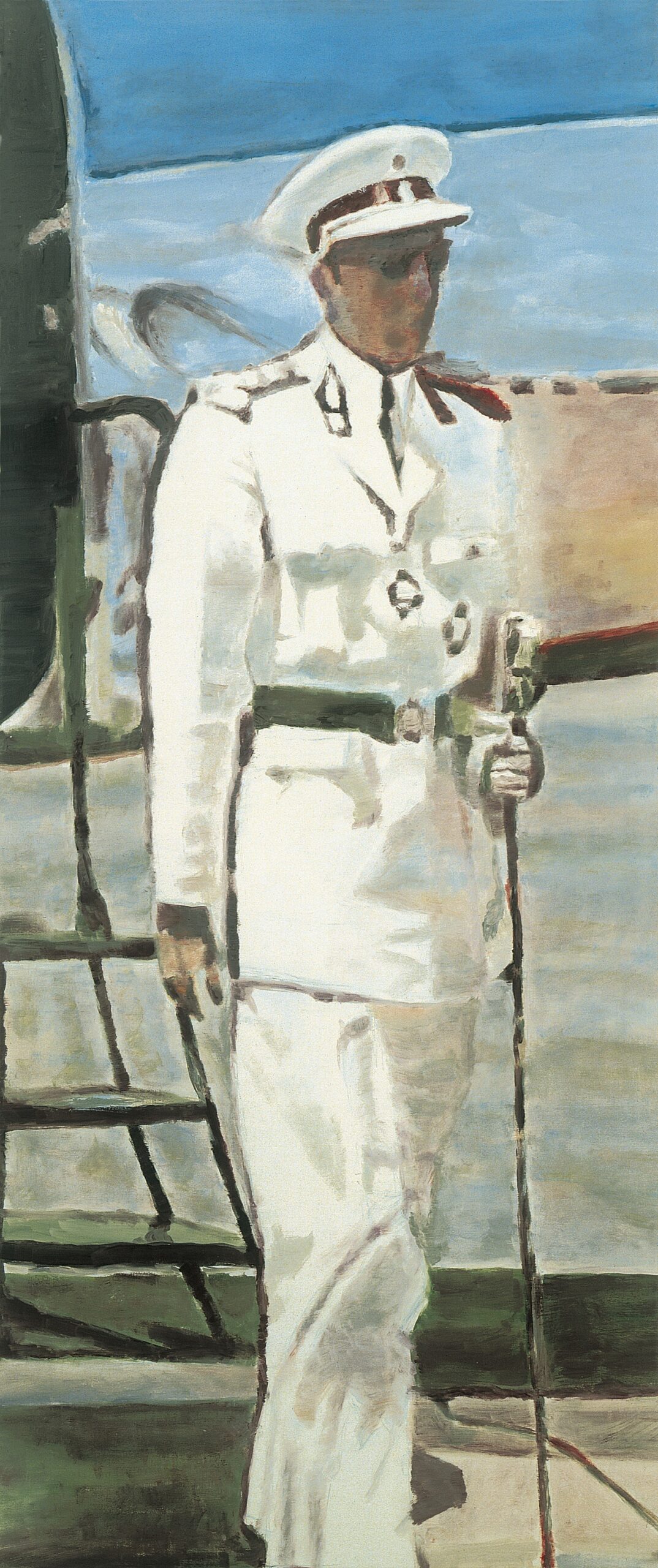

Mwana Kitoko

Mwana KitokoⒸ Luc Tuymans

Though rife with vague and fragmented depictions of Belgian colonial history, the series also directly references the well-known portrait of Patrice Lumumba and archival images of King Boudewijn’s visit to the Congo. Though the exhibition was hosted in New York and later at the Venice Biennale, it was crafted primarily for a Belgian audience: Tuymans wanted to stimulate discussion in Belgium, though he emphasized that his intention was sooner to “ask questions” than to “make statements”.

Mwana Kitoko cannot be interpreted outside the context of the exploratory committee which had been called by Parliament shortly theretofore to investigate Belgium’s involvement in the 1961 murder of Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected Prime Minister of the independent Republic of the Congo. Goundbreaking books by Ludo de Witte (Crise au Congo and L’Assassinat de Lumumba) and by Adam Hochschild (King Leopold’s Ghost) were also published around the same time. Together, these events brought the (post)colonial question into both the national and international spotlights.

Around the same time, Jan Fabre, Wendy Morris, and Sarah Vanagt incorporated postcolonial themes into their work in extremely varying ways. In 2002, Fabre installed an exhibition in the Hall of Mirrors at the Royal Palace in Brussels upon the invitation of the Belgian Queen Paola. He covered the ceiling with the beetles that were typical of his oeuvre and called it Heaven of Delight. It later transpired, however, that this work incorporated scathing references to the colonial past in the Congo. The insects he used were a specific species found in the Congo, and secret messages like skulls and amputated hands were hidden symbolically in the exhibition. Fabre would go on to explore these motifs in later projects.

Meanwhile, Sarah Vanagt resolved to make a film about the 1994 Rwandan genocide after meeting a Rwandan professor at the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren (RMCA, known since 2018 as the AfricaMuseum). Her point of departure for the project was a 1959 film about Witte Pater missionaries in Africa, made shortly before Congolese independence. At the time the film had never been shown, but the Rwandan professor had participated in its production as a young child. With his help, Vanagt was able to find the source in the KADOC archives in Leuven.

After Years of Walking was finally produced in 2003 thanks to a combination of coincidence, targeted archival work, and Vanagt’s background as a historian. In the documentary she travels to Rwanda, historical film in hand, and conducts interviews about the temporary abolition of historical study in the wake of the 1994 genocide.

After Years of Walking

After Years of WalkingⒸ Sarah Vanagt

Morris saw colonialism as a form of cannibalism

Wendy Morris, a filmmaker of South African heritage, also produced a film in 2003: A Royal Hunger. This six-minute-long animation reflected upon the the way the colonial past is represented in Belgium, examining the role of Leopold II and the institution of the RMCA. The film investigated the North-South relationship from both a mental and a moral point of view, considering the physical and materio-economic relationships in context. Morris saw colonialism as a form of cannibalism. She incorporates this notion into her film by depicting cans of pickled meat based on a gruesome myth that had circulated in the Congo for many years: Belgian colonizers were known to eat amputated human hands. She used this myth to ingenious effect in her work.

Vincent Meessen, Sven Augustijnen, and Renzo Martens also went on to use documentary film to turn their gaze to the colonial past – again, in extremely varying ways. Each artist navigated the grey areas between fact and fiction, an approach that is known as documentary fiction.

Patrick Bernier & Olive Martin, L’Echiqueté, 2012, installation for Vincent Meessen

Patrick Bernier & Olive Martin, L’Echiqueté, 2012, installation for Vincent Meessen© Alessandra Bello

Vincent Meessen worked on Ritournelle from 2005 to 2012, which became an archetypal example of his style. Meessen often uses a historic datapoint, concept, or figure as his starting point. For Ritournelle, this became the French author Raymond Roussel, whose novel Impressions d’Afrique had strongly contributed to the Western image of the African continent when it was published in 1909.

Meessen took this novel and built an entirely new discourse around it, thereby deconstructing the typical Western perspective and flipping the conceptual elements of Roussel’s novel on its head. Rather than develop this work solely from the Western perspective, Meessen also created a musical composition for the project together with the Ougadougou-based rap group WenTeng Clan.

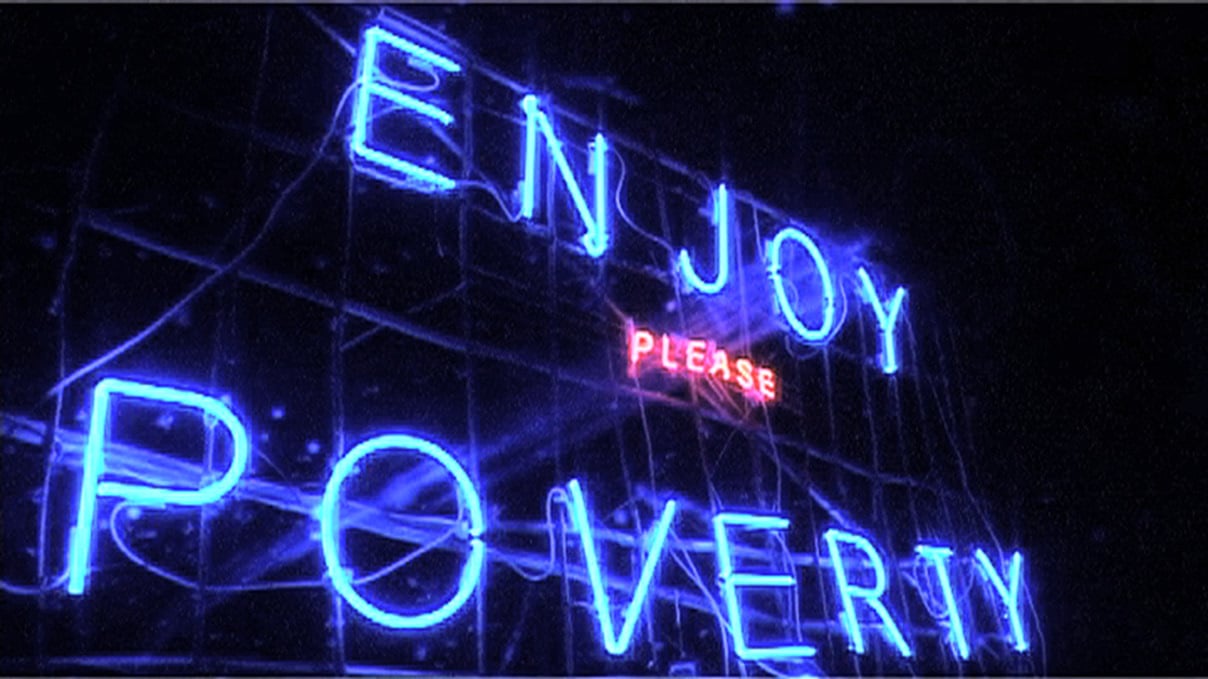

Still from Enjoy Poverty, doocumentary film, 2008

Still from Enjoy Poverty, doocumentary film, 2008Ⓒ Renzo Martens

Meanwhile, Sven Augustijnen often reflected on truth and the role of the press in his work, and on the relationship between the past and present. In doing so, he dove into archives to look for untold stories. Thus, he began to search for Lumumba’s murderer in the film Cher Pourquoi Pas? (2007). Renzo Martens also created a stir with his 2008 project Episode III: Enjoy Poverty. In this documentary style film he traveled from one Congolese village to the next armed with a neon sign that read: Enjoy Poverty. This was met with a great deal of criticism in the press as well as among the public. But that was the point: Martens wanted to confront the West with the viscious cycle of poverty in the Congo that it systematically upholds.

Fifty Years of Independence

In 2010, the fiftieth anniversary of Congolese Independence, among other African nations, brought a great deal of extra attention to the continent. In the art sector, too, postcolonial thought gained traction. The artists already mentioned in this article dove deeper into their practices, while artists like Maarten Vanden Eynde, Otobong Nkanga, and Sammy Baloji joined them at center stage.

Maarten Vanden Eynde created I Want That You Want What I Want That You Want, and In_Dependance – a project clearly linked to fifty years of Independence. The first was a reworking of a Stihl chainsaw, here crafted out of ebony by a Cameroonian and then sold as a work of art by Vanden Eynde at the Art Brussels auction. With this order of events – African raw material brought via African labor to the European market – the artist endeavored to underscore the often exploitative progression of international trade between Africa and Europe.

Meanwhile, In_Dependence was born in collaboration with the Cameroonian artist Alioum Moussa, dealing with the notion of independence on many levels: from the political to the personal. Fifty sets of black and white t-shirts were distributed among interracial couples in Douala; the black shirts with the text “In”, the white shirts with the text “dependance”. Photographs of the couples wearing the t-shirts were then printed on 1,500 posters, and publicly distributed. The African continent and especially the Congo would go on to figure in Vanden Eynde’s work time and time again.

Maarten Vanden Eynde and Alioum Moussa

Maarten Vanden Eynde and Alioum Moussa© Marjolijn Dijkman

Otobong Nkanga, a Nigerian-born Antwerp-native, started to develop Social Consequences in 2009. She worked on the first three parts of this four-part series until 2010; the fourth followed in 2013. In Social Consequences, personal and societal reflections come together in her recognizable style, which makes use of acrylics and stickers. The series incorporated themes like exploitation, dispossession, alienation, and the abuse of landscape and labor.

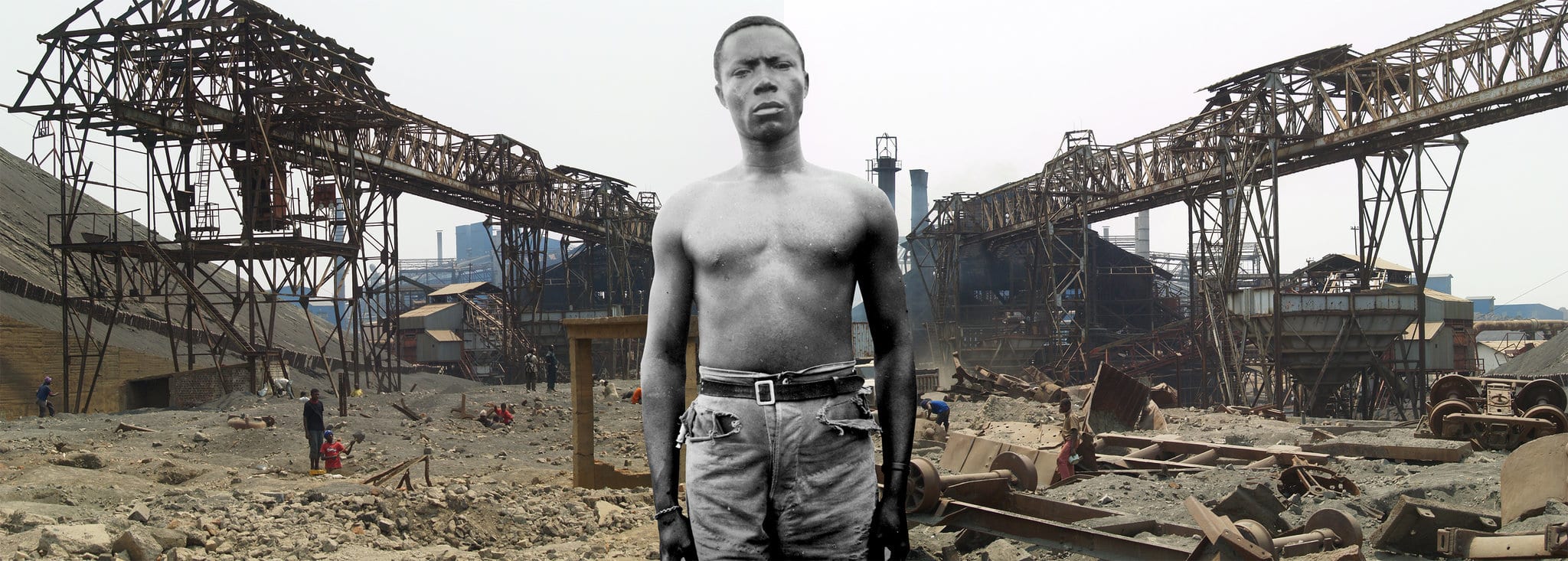

Untitled 17 from the series Mémoire

Untitled 17 from the series MémoireⒸ Sammy Baloji

The Congolese artist Sammy Baloji had been active for several years prior to 2014, known for the project Mémoire / Kolwezi (2006), among others. With a collage-like technique that combined archival materials and contemporary photos, he sketched the historical progression from colonial to neocolonial exploitation. He collaborated with the Belgian cultural institution Africalia (2012) and the RMCA. Then, 2014 became a turning point in his career. For the first time, he worked together with Mu.ZEE in Oostende, which resulted in the exhibition Hunting & Collecting. In 2015 he accompanied Vincent Meessen to the Venice Biennale, and in that same year again collaborated with Mu.ZEE on the exhibition European Ghosts. The exhibition offered an incredibly critical view on both Belgian and European colonial histories.

Venice (again)

The 2015 Venice Biennale was a key moment in the art world when it comes to dealing with postcolonial questions, as much for Belgium as for the international community. The critical art historian Okwui Enwezor, born in Nigeria, became the first African in the 120 year history of the Biennale to be chosen as curator. His Biennale All The World’s Futures unapologetically put politics on the agenda, and was an active attempt at decolonizing the Venice Biennale. Enwezor took a deep dive into the past, and simultaneously fixed his gaze on a future that might break away from that past.

With Personne et les Autres by Vincent Meessen in 2015, the Belgian pavillion was once again filled with postcolonial inspiration – the first time since Mwana Kitoko by Luc Tuymans in 2001. But Meessen took it one step further than Tuymans: he broke from the tradition of a solo exhibition and invited at least ten different artists from around the world to participate. In Personne et les Autres, they reflected upon political themes grounded in their shared interest for research and colonial history. Like many works of postcolonial art, the exhibition was also the result of an “archival impulse”. This term, coined by the art critic Hal Foster, points to the increasing use of archival research and materials in contemporary art. It was therefore no coincidence that Personne et les Autres equally explored the sometimes ambiguous relationship between scholarship and art.

Personne et les autres by Vincent Meessen

Personne et les autres by Vincent MeessenⒸ Adam Pendleton

In 2017, Otobong Nkanga and Maarten Vanden Eynde were two of the four finalists for the Belgian Art Prize, biannually awarded by the Brussels-based arts center BOZAR. Nkanga won the jury prize, and Vanden Eynde won the public prize. The fact that two artists whose work deals with societal themes, the African continent, and the colonial past both won this prize in the same year confirms that the postcolonial question has fully permeated the Belgian art scene. The next year, Otobong Nkanga went on to win the Ultima prize for the visual arts, an annual culture award granted by the Flemish Community.

Ⓒ Octobong Nkanga

Postcolonialism maintains a strong presence in the visual arts and in so doing, step by step, changes our perspective on the art world and on the relationships within it.