Do You Know What ‘a Flandrian Facial’ Is?

Linguist Fieke Van der Gucht also likes biking and flandriens. During a wet race day, she is downwind of two crazy Englishmen on bicycles. Did she already know that the Flemish tenacity for cycling inspired the English to invent much of today’s cycling lingo?

Karel Van Wijnendaele, sports journalist and founder of the Tour of Flanders cycling classic

Karel Van Wijnendaele, sports journalist and founder of the Tour of Flanders cycling classicI love reading and writing, walking and racing. Occasionally, those passions go hand in hand perfectly. As an editor for Lannoo, for instance, I have been cycling through the extraordinary voluminous manuscript Van koersen en coureurs, a chronicle of 120 years of racing by Robert Janssens. He talks about, for example, Karel Van Wijnendaele, who was not called Van Wijnendaele, but Steyaert. Yet: the name of the castle from his village sounded a lot less prosaic. Karel, Koarle for his (West-Flemish) friends, was initially a cyclist, but not a very successful one. As the story goes, he drove into the pond out of pure exhaustion during a tiresome race. Let’s put it this way: Koarle was better at writing about the race, than performing in the race itself.

While I’m reading in Van koersen en coureurs

about how Karel van Wijnendaele’s Sportwereld

was created in 1912, my thoughts wandered off; I find myself leaving the office and getting up on my imaginary racing bike. I remember how I got thrown off the peloton during a very stormy Ghent-Wevelgem Cyclo 2015. I tried to warn the rest of the group of cyclists, however the calls were drowned out by the sound of the wind. My partner and two friends became smaller, my pedals slowed down. My wet hair stuck to my cheeks, tears and snot were given free rein, and my socks were also no longer dry either. I threw myself against the wind; the fields passed by me more and more slowly.

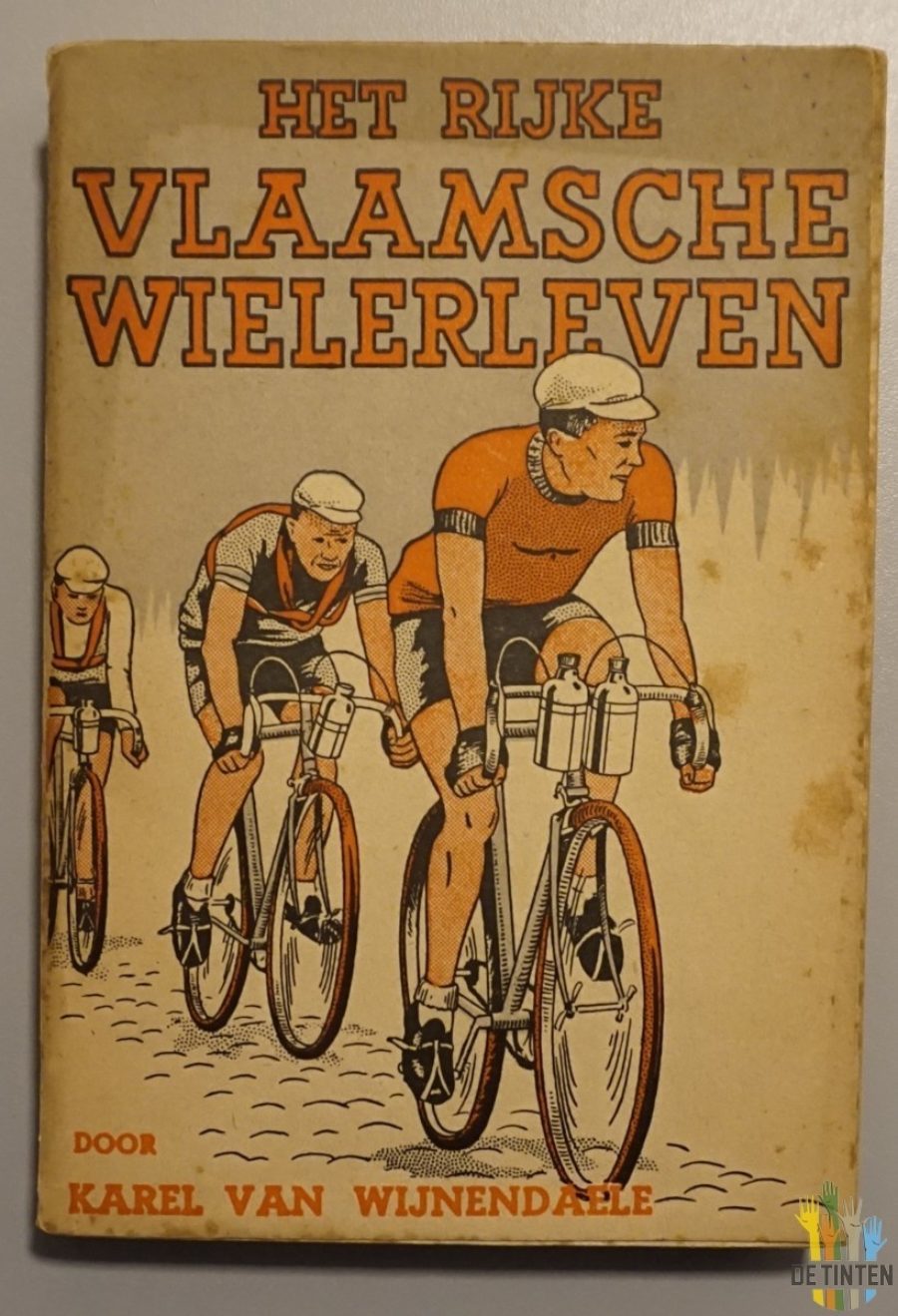

Feeling increasingly cold and slowing down my cycling speed, I remember how I thought of that one sentence from Het rijke Vlaamsche wielerleven (1943) by Karel van Wijnendaele: ‘It was terrible, and when we returned home, with the wind crying and the rain crushing, then we repeated it ourselves: “No, it’s not human anymore!”’ Karel lacked strength in the legs for a professional cycling career, but, according to the pioneer in Flemish sports journalism, ‘learned to discover with the pen for what [he] couldn’t find with the legs’.

His pen was looking for a concept with which those “keikoppige” (extremely stubborn) Flemings that ‘had to work hard for their wretched living conditions’, could identify themselves with their counterparts on a bicycle. He eventually found the concept of flandrien, originally an insulting nickname for Flemish seasonal workers in northern France and Wallonia. Karel turned the from-origin-insulting nickname into an honorary title for Flemish cyclists who were poor and popular, physically strong and strong-willed, at first in track cycling, but later also in road cycling. Flandriens would seemingly race without strategy and always attack; they would especially flourish in terrible weather. Karel kept repeating this until “the Fleming” started to believe it!

While I further tarnished the whole concept of the flandrien, during that Ghent-Wevelgem in 2015, two life-saving angels emerged: John looked like a dwarf and Russ looked like a giant. They were both lost. We made a deal: I would guide them to the Kemmelberg, and they would put me out of the wind and bring me back to my love and the others. This is why they went down to Flanders every year, they gasped: for the cobblestones and cold, the mud and the rain. That they loved aimlessly pedalling through the flat, windy landscapes in Flanders. That they imagined themselves to be flandriens in their deepest thoughts.

A 'Flandrian facial'

A 'Flandrian facial'Back to the question of whether I knew that the Flemish intransigence inspired the English to make a lot of cycling expressions? Did I already hear of the expression at his Flandrian best? You use it for the shorts, arm- and leg protectors, gloves and overshoes that someone persistent puts on to go cycling in cold and rainy weather. Or did I already hear of a Flandrian facial, a muddy face, and a Flemish tan line, there where the shorts stop and muddy bare legs start? And – meanwhile, the dwarf and the giant pointed at the splashing wet road surface – the reflection of a cyclist on the wet asphalt is called a Flemish mirror in English. That’s what I was supposed to know as a linguistic cyclist, right?

A Flemish tan line

A Flemish tan lineI found new courage and a second breath. Charles taught his people not only how to read, but also how to talk about the course, even more than a hundred years later. To this day, we are still friends: the British flandriens and I.

I wander off my imaginary bike, into the office. Whether Koarle hears in italics or between single quotes, that will be the focus again.