Last year, the Anglo-Netherlands Society of London, to mark its centenary, published North Sea Neighbours, a collection of wide-ranging essays on important aspects of Dutch-British interaction across the sea. In his contribution, Professor Reinier Salverda of University College London (UCL) zooms in on the big and often funny impact that interaction has on each other’s language.

In 1992, in the run-up to the Maastricht Treaty, I was contacted at UCL by the BBC’s Pronunciation Unit. They wanted to know how to instruct their newsreaders on the proper way of saying ‘Maastricht’ in Dutch. I explained that it is Maastrícht, with main stress on the second syllable, and this was duly incorporated into the BBC’s Pronunciation Guidelines. Then, along came Dutch prime minister Kok who, at his closing press conference, undid our efforts by saying Máastricht, with main stress on the initial syllable. The rest, as they say, is history, and today, Kok’s English adopted stress pattern is heard everywhere, as in the pronunciation of Àmsterdam instead of Amsterdàm.

Pieter Sjoerds Gerbrandy, wartime leader of the Dutch Government in exile in London. His English was poor.

Pieter Sjoerds Gerbrandy, wartime leader of the Dutch Government in exile in London. His English was poor.A similar Anglo-Dutch language mix-up – this time not in sound but in meaning (and also, a bit less successful) – happened when an earlier Dutch prime minister, Gerbrandy, wartime leader of the Dutch Government in exile in London, arrived for his first meeting with his British counterpart, meaning to say, in good Dutch fashion, ‘Goedendag’, and greeting him with a hearty ‘Goodbye, Mr Churchill!’ – which of course rather startled and amused his host.

With a little more success an Amsterdam shoe shop in the 1990s launched a poster showing five kids jumping up and down in their brandnew shoes underneath the headline ‘Spring’s in the air!’. This sentence looked and sounded English, and meant something too [‘Springtime is upon us’], but the point it made was effectively a Dutch one, to a Dutch audience, playing on the word ‘spring’, meaning ‘to jump’ in Dutch. And some twenty years later, in 2018, the same headline was used again to advertise a springtime NASA event of the Dutch Mad Science Organisation.

A Dutch expression translated literally into English. Funny, but incorrect.

A Dutch expression translated literally into English. Funny, but incorrect.Such crossovers between our two languages – mixing elements from English into Dutch, from Dutch into English – are not uncommon in Anglo-Dutch communication. As a consequence, in between the respective standard varieties of Received Pronunciation BBC English (RP) in the United Kingdom and Algemeen Beschaafd Nederlands (ABN) in the Netherlands, we can today identify a wide range of intermediate interlanguage varieties, usually arising through oral contact in everyday colloquial language contact situations.

In the cases mentioned above we see how, while we are producing language, we simultaneously also produce variation, all the more so in language contact. In the course of the long history that we shared during centuries of contact, exchange and transfer across the North Sea, mixing in language learning has generated varieties such as Netherdutch and Nederdutch.

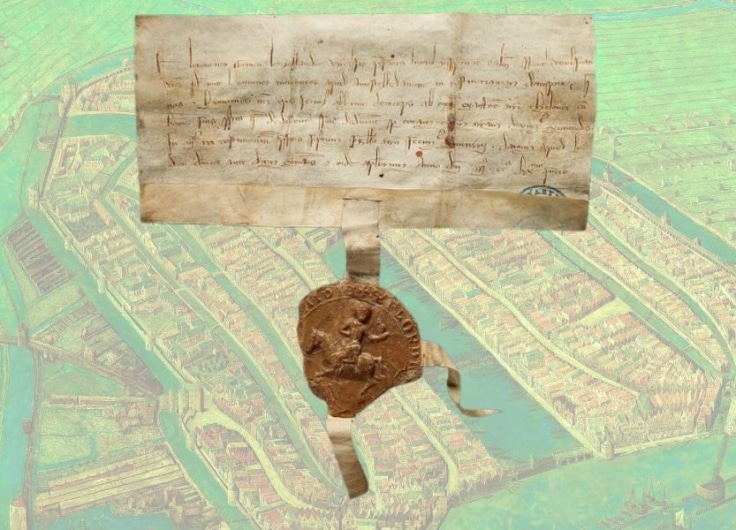

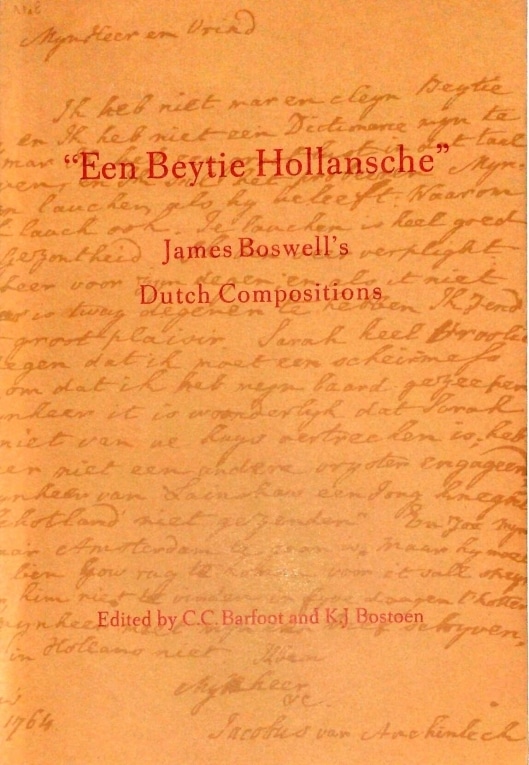

In the 1760s, when James Boswell in Utrecht attempted to learn writing Een beytie Hollansche in his letters, he mangled the language so much that his friend Archibald Stewart in Rotterdam needed ‘to employ a Tovenaar or Sorcerer … to explain it to me’. Ever since, the vicissitudes of transmission, borrowing and transfer have occasioned all kinds of shifts and changes – kingfishers in Dutch are not what one would expect, koningsvissers, but something entirely different, viz. ijsvogels (i.e. ice birds); words undergo changes of meaning in transit: a plaid in the Netherlands is a type of blanket, while in Scotland it is a tartan; and there are English words that only exist in the Netherlands such as smoking (tuxedo, dinner jacket) and al/risk (all risks insurance). Key words that are typically Dutch, such as ‘gezellig’: can be hard to translate – ‘cosy’ doesn’t quite do it – and the other way round, consider how difficult it is to render English stereotypes of the Dutch, such as dutch courage, double dutch, or The Undutchables, into a reasonable Dutch equivalent.

It is difficult to render English stereotypes of the Dutch, such as dutch courage, double dutch, or The Undutchables, into a reasonable Dutch equivalent

Often, such formations bring a smile to one’s face. And, actually, we find the same mechanisms operating in language play. Crossover varieties like the ones above, resulting from Anglo-Dutch language contact, may reveal interesting and surprising gaps between our two languages. Language play exploits these gaps in almost boundless variety, ranging from double dutch, gibberish, klingklang and kolder, to the nonsense of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear. The British just love puns, especially in their newspaper headlines.

It is this – the humour of language contact – that we shall now consider more in depth. How come language play can make us smile? What structures and processes are at work here? And what can we say of the dynamics and creative potential of these mixed intermediate varieties? Translation here offers an interesting field of study. Take, first of all, one of Rudy Kousbroek’s logological experiments on the Dutch language, his literal word-by-word translation into English of the Dutch tale Klein Duimpje (Little Thumbkin):

There was once a poor woodchopper. ‘This woodchopping’, he said one day to his woman, ‘there sits no dry bread in it. I work myself an accident the whole day, but you and our twelve children have not to eat.’

‘I see the future dark in,’ his woman agreed.

‘We must see to fit a sleeve on it,’ the woodchopper resumed; ‘I have a plan: tomorrow we shall go on step with the children, and then, in the middle of the wood, we’ll leave them to their fate over.’

Mark Twain did exactly the same when he retranslated a French translation of his own story The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras Country of 1865 back into English. Like Kousbroek’s piece, Twain’s too is in English, but it isn’t English as we know it, since the other language – in Kousbroek’s case Dutch, in Twain’s case French – is shining through clearly.

The dutchified English in Kousbroek’s Little Thumbkin tale is extremely funny; so too is his Dutch translation in 1978 of Raymond Queneau’s Exercices de style, which is just as brilliant as Barbara Wright’s English translation. And the resulting mix of languages and styles in these texts is of the same irresistible humour that made ‘Allo ‘Allo one of the most enduringly popular BBC TV comedies ever.

Shortly after Kousbroek’s tour de force, Battus (pseudonym of Hugo Brandt Corstius) in 1981 published his ‘seminal work on Dutch wordplay’ (as Eckler put it in 2001), a vast compendium of the new discipline of Recreational Linguistics, or, as Battus himself described it, of ‘Dutch on Holiday’, not Netherlandish then, but Opperlands – around the same time as Gyles Brandreth’s Wordplay (1982) on the English side. Future language research in Recreational Linguistics owes a great deal to the First Principle formulated by Battus: Wat kan dat mag, en wat niet kan dat mag helemaal – what is possible is allowed, and what is not possible is allowed absolutely.

The work of these and other pioneers in Recreational Linguistics opened many new vistas, and it was in their spirit that in 1994-95 we got our second case, an eye-catching advertising campaign for the launch of a new Dutch beer, Oranjeboom, through a series of strange statements appearing, one after the other, on the side of London’s double-decker buses:

Taak uur tast buds voor aar ry de

U vil nyver hier aan ie tin negatief a bout de tast of Oranjeboom

Zeems lik dubbel Dutje? Wel zuur prijs, zuur prijs, et ijs

Stuf de tur key ei mof voor’aan Oranjeboom.

Taking the last of these four, we note that the words in this sequence do look a bit like Dutch. But they aren’t quite. Nor is this in any way a sentence that is Dutch or makes much sense. Even to a Dutchman, this undoubtedly is a case of double dutch and gibberish.

So, what does it mean? For decoding purposes, a good start would be to ignore both spelling and writing. Just use your inborn English and in what way? As they say, poetry is what gets lost in translation. We will never produce a 100% match, perfection does not exist, at most we may achieve an optimum, an approximation – it is precisely the bandwidth of variation in language, grammar, dictionaries and texts chat opens up a space of freedom and play, crucial preconditions for generating dynamics in cultural and linguistic interaction.

Our final case is that of the immortal hero of Leo Rosten’s The Education of Hyman Kaplan (1937): a Jewish immigrant in New York learning English in night school, where he gets involved in a class discussion of the question: What is the past tense form of the English verb ‘to bite’? Looking for an answer, the whole class rejects ‘bited’ – since to bite, after all, is not a regular or weak verb. A member of class then comes up with the correct form, bit, and the teacher explains chis by analogy: to bite goes like to hide – hid– hidden; so it is only logical that we get bite – bit bitten. At this point, however, Hyman Kaplan chips in. He feels that the past tense of bite should not be bit, but… bote. When asked why by the teacher, Kaplan offers his own ‘dark baffling logic’ in matters of language, asking: ‘Vell… if is write, wrote, written so vy isn’t bite, bote, bitten?’.

And indeed, why not? Kaplan’s Yiddish logic, when applied to the English language he is trying to learn, plays a joke on the lack of regularity in the English strong verb ‘system’, while at the same time subverting the arbitrary ‘just because’-logic of his teacher’s analogic explanation: there is no real reason why it should be bit rather than bote – it just happens to be so.

So why not adopt Kaplan’s analogy rather than the teacher’s? Kaplan’s bote may strike one as obvious nonsense, but it is not totally devoid of sense: it is more like a child’s mistake, innocent and slightly off, just following the wrong rule, hence easily corrected. The fun part here is that Kaplan, throughout Rosten’s novel, appears to be walking to a slightly different music, and talking to a slightly different logic than the rest of his class; and these would appear to be basic features in any language play.

Similar examples for Dutch – of things meaning one thing in Dutch while simultaneously saying something entirely different in English, and vice versa – can be found in the amusing account of the idiotic grammar rules and insane conversations one may run into when setting out to learn Dutch, in Cuey-na-Gael’s An Irishman’s Difficulties with the Dutch Language (pseudonym of J. Irvin Brown; first published in 1908, and regularly reprinted ever since until today).

What we encounter in Kaplan’s speech is the production of new and nearly possible variants in English. Language users, while producing their expressions, are evidently capable, at the same time, of playing with them. If someone can produce a linguistic expression, they can usually also produce all kinds of variations on it, creating new forms to satisfy new needs of communication and expression.

If someone can produce a linguistic expression, they can usually also produce all kinds of variations on it, creating new forms to satisfy new needs of communication and expression

Just think of the many irregularities in language – as did Mark Twain, when he said about the strong verbs of German that here we have a language with more exceptions than rules. To others, it is long words that may prove irresistible, as in the musical Mary Poppins (1964) that gave the world Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious.

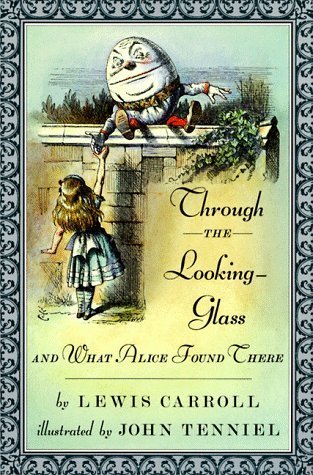

Others may be more interested in the play of children’s rhymes and the nonsense poetry of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear. Or one may engage in the play of sounds and letters in Scrabble, in word puzzles, in jeux de mots, in anagrams, puns, and the innumerable other ways of disguising words and meanings that we find in ancient cryptography, magical practice, tongue twisters, taboo and euphemism.

Linguistic creativity generates variation, and in that variation we language users can find the space within which to play

As we see, linguistic creativity generates variation, and in that variation we language users can find the space within which to play. Today, the use of language play and its principles is being implemented in the field of language learning following the stimulating Erasmian treatise Language Play, Language Learning (2001) by Guy Cook.

The moral: people who play together, stay together, with language play as their key, while challenging us to engage – certainly in these days of Brexit means Brexit – with the question posed by Humpty Dumpty in Through the Looking Glass:

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in a rather scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more or less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master – that’s all.”