Duelling in the Dunes. When Tourists Fought in Flanders

In the 19th century, a very particular kind of tourist came to Flanders: foreigners looking for a quiet place to fight. They came to settle debts of honour out of the public eye, and to avoid the increasing prohibitions on duelling in their home countries. Any trouble with the Belgian authorities could be avoided, hopefully, by a swift return home.

The conventions of duelling were well-established by the beginning of the 19th century. When one man felt another had offended his honour, he would issue a challenge to fight. The time, place and terms for the combat (swords or pistols, the number of shots, the distance and signal, etc) would be arranged through seconds, friends on each side who also attended the duel to negotiate its conclusion.

Simply going through with the combat was sometimes enough, a demonstration that both sides had the courage and the willingness to defend their honour in a gentlemanly way. ‘I faced his fire’, is how a number of duellists put it. In other cases, a wound was necessary, perhaps slight, perhaps serious enough to prevent further combat. A fatality settled the matter definitively.

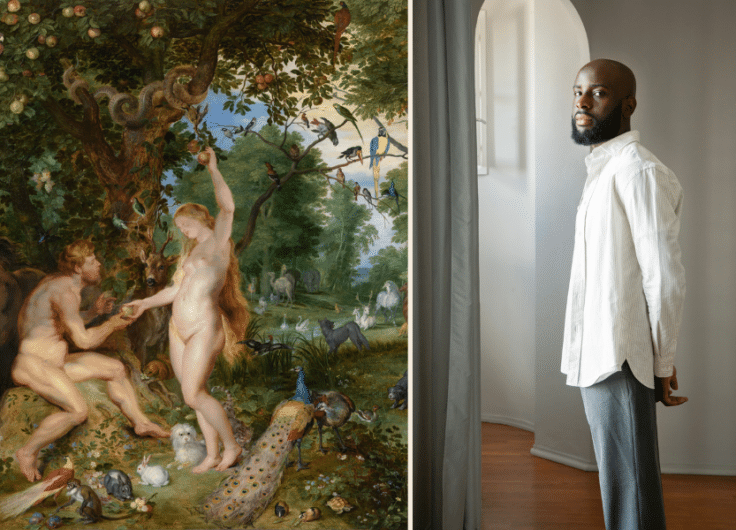

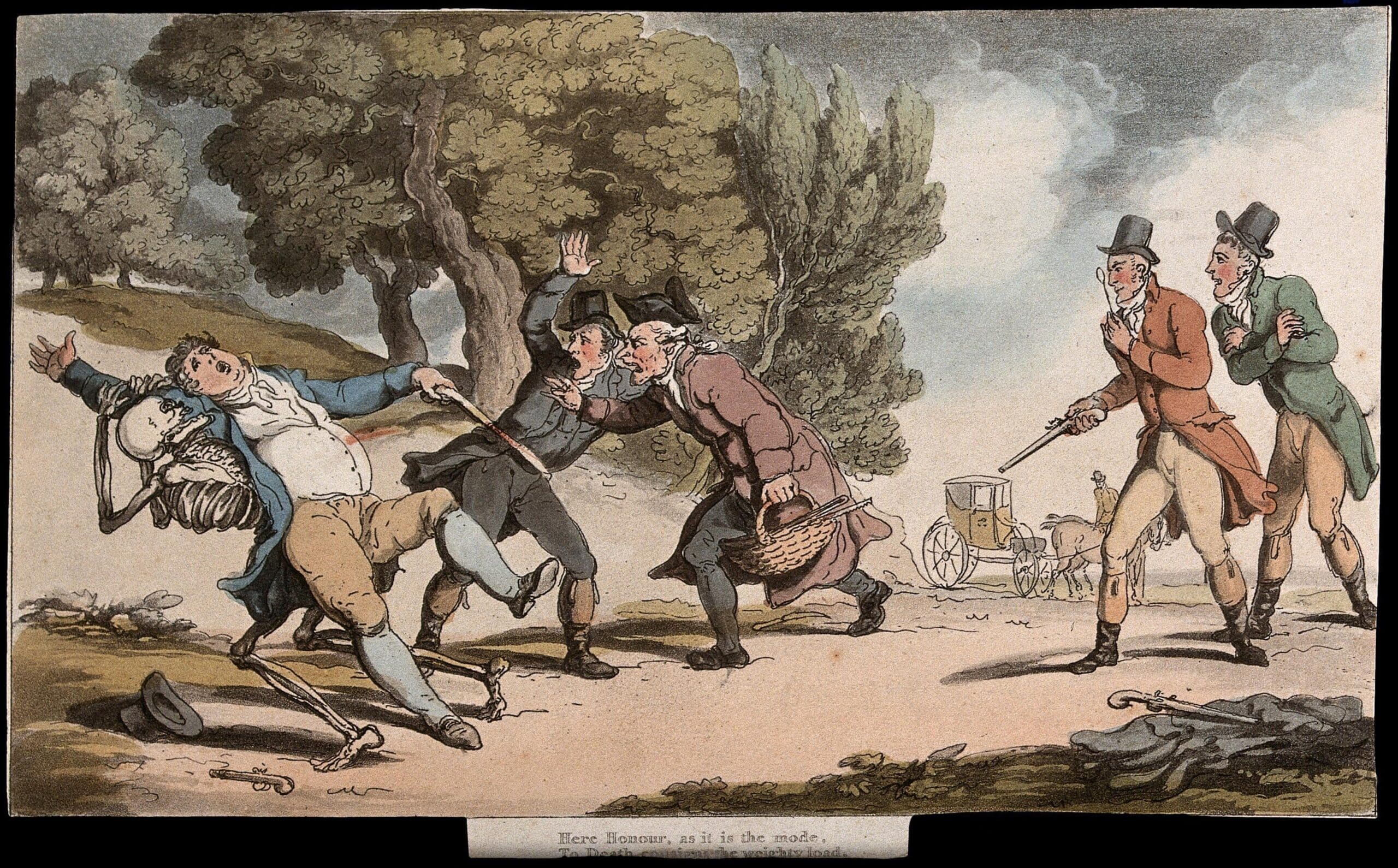

At the beginning of the 19th century duelling held a powerful place in the public imagination, for example The Dance of Death: The Duel (1816), a coloured aquatint by Thomas Rowlandson.

At the beginning of the 19th century duelling held a powerful place in the public imagination, for example The Dance of Death: The Duel (1816), a coloured aquatint by Thomas Rowlandson.© Wellcome Collection

Secrecy was imperative when preparing an “affair of honour” but, once concluded, the news could circulate. Accounts of duels frequently appeared in newspapers, often based on reports written by the seconds, or journalists invited along as professional witnesses. Reports would also appear when the law succeeded in preventing a duel.

In case of interruption, it was considered part of the code in Britain and Ireland that the seconds should immediately arrange a new meeting abroad. Calais and Ostend were popular destinations, with some Calais duels moving over the border to Belgium if the French gendarmes proved too attentive. But getting to the Continent was not a simple matter, particularly if the intention to fight was known.

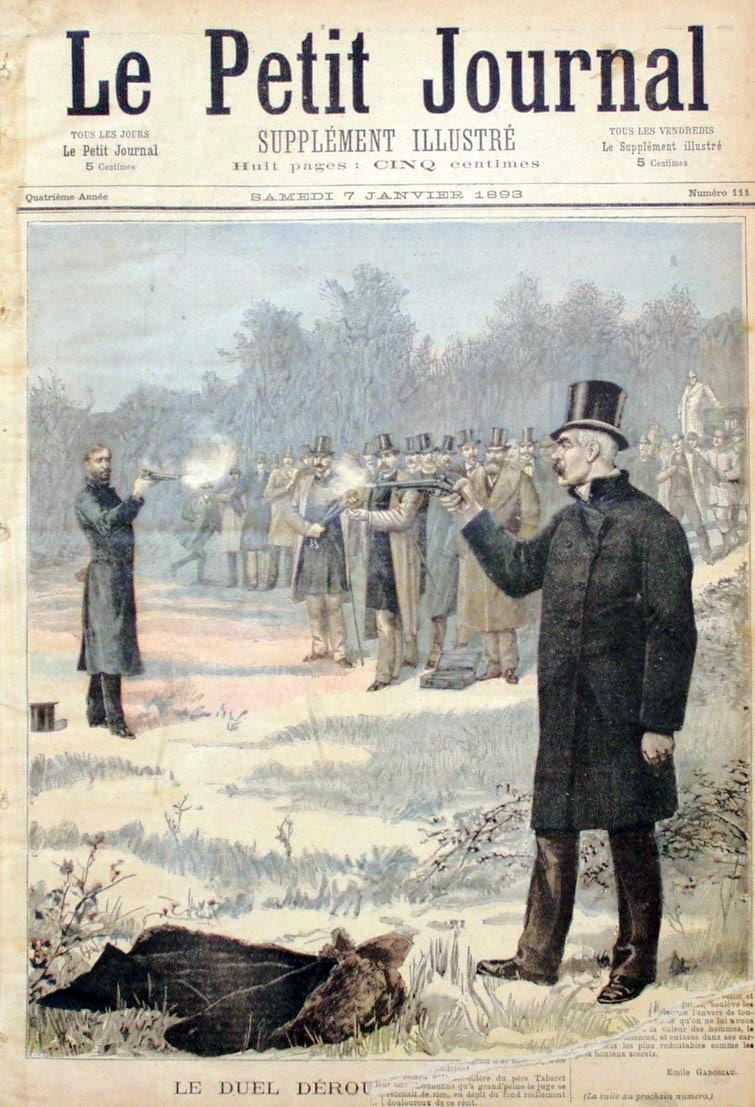

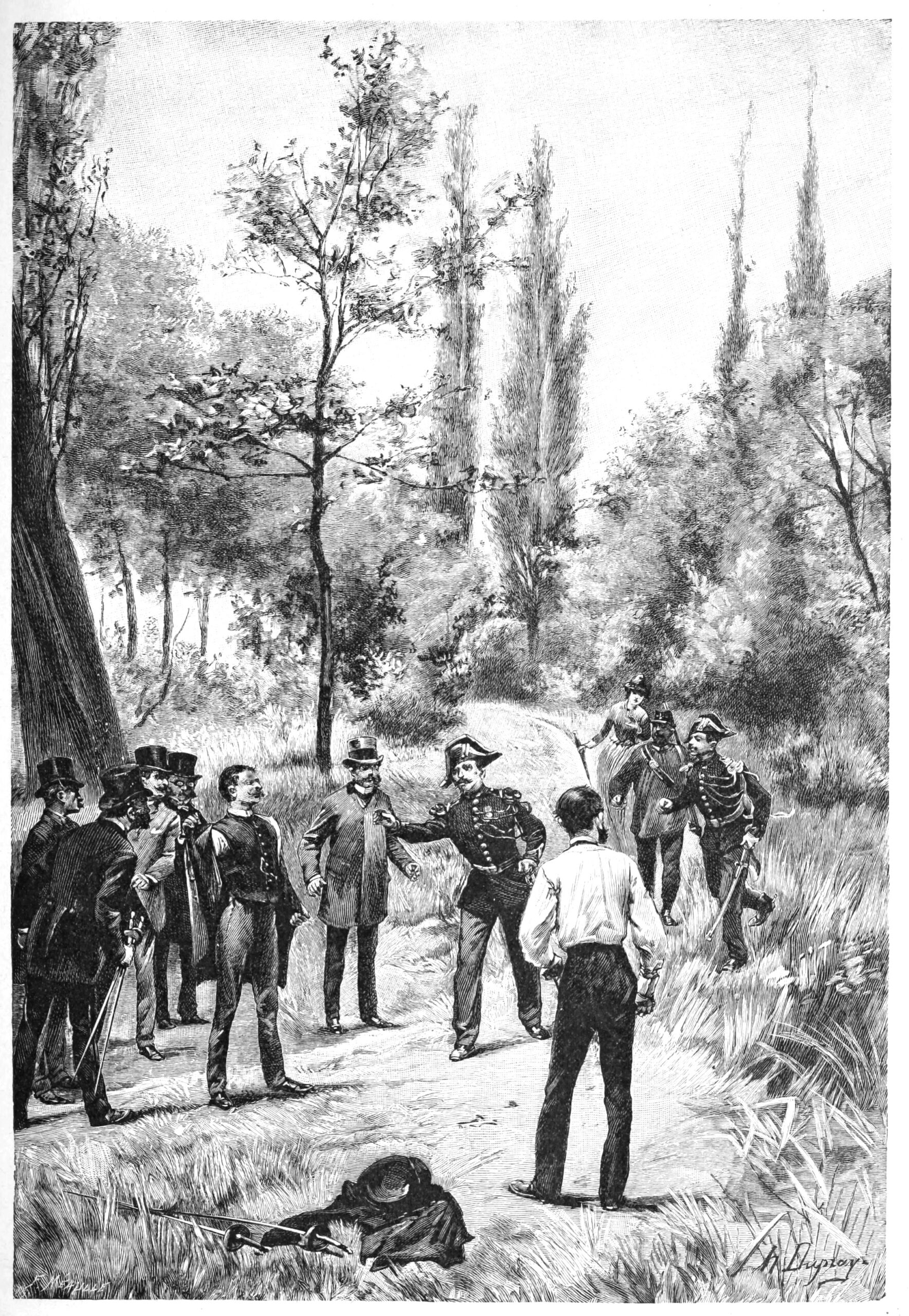

In France, political duels continued through the 19th century. This duel, featured on the cover of Le Petit Journal in January 1893, involved Paul Déroulède and Georges Clemenceau, both then members of the Chamber of Deputies.

In France, political duels continued through the 19th century. This duel, featured on the cover of Le Petit Journal in January 1893, involved Paul Déroulède and Georges Clemenceau, both then members of the Chamber of Deputies.© Wikipedia

In 1815, a duel between the Irish nationalist firebrand Daniel O’Connell and Robert Peel, the Irish secretary in the British government, was prevented when O’Connell was arrested and bound over to keep the peace. Unable to fight in Ireland or Britain, they arranged to meet in Ostend. As well as being a legal necessity, it suited Peel to settle the matter away from O’Connell’s supporters. ‘It is much better to go to Ostend than to be, in any event, knocked on the head in the county of Kildare,’ he wrote to a friend before leaving.

Peel and his seconds crossed easily from Ireland to Wales, travelled undisturbed through England and on to Calais, before making their way up the coast to Ostend, then newly part of Dutch territory. They found lodgings a short distance out of the city, calling twice daily at the post office for reports of O’Connell’s progress. This was not so smooth. An attempt to travel directly from Ireland by sea was thwarted, and when he crossed into Wales the police were waiting to intercept him. He dodged them, but was arrested in London. Five days later, one of O’Connell’s friends finally reached Ostend, and it was decided to postpone the duel. While the two never did come to blows, the matter was only formally closed when O’Connell apologised in 1825.

Even when both opponents managed to get across the Channel, fighting on unfamiliar ground was no simple matter. In 1830, Lord George Bingham was challenged to fight in Ostend by Major Charles Fitzgerald, who felt a promise of patronage had not been fulfilled. He also thought Bingham would not fight, which turned out to be an error.

The principals and their seconds would often travel separately, to avoid arousing suspicion

The duel was set for 6am, one mile from the gates of Ostend on the road to Brussels. Bingham and his seconds appeared on time, but found no-one at the appointed spot. Fitzgerald arrived 45 minutes later, protesting that there was another road from Ostend to Brussels, and that this was where his second had gone, along with his pistols. He offered to fight with Bingham’s pistols and a replacement second; Bingham’s party agreed, as long as the first second did not show up within the time originally agreed for the duel. When that deadline arrived, the first second had not appeared, and the second second had gone off to look for him. At this point, Fitzgerald’s evident reluctance to fight got the better of him: he withdrew his challenge, and the farce ended without a shot being fired.

While this is an extreme case, most likely contrived by Fitzgerald, it highlights some of the common difficulties faced by visiting duellists. The principals and their seconds would often travel separately, to avoid arousing suspicion, only meeting at a hotel the night before the duel, or at the appointed time for the combat. Then a good duelling ground had to be found: secluded, flat, and shady, so that neither man had the sun in his eyes. If this took too long and the visitors were spotted, then the Belgian gendarmes were generally quick to intervene.

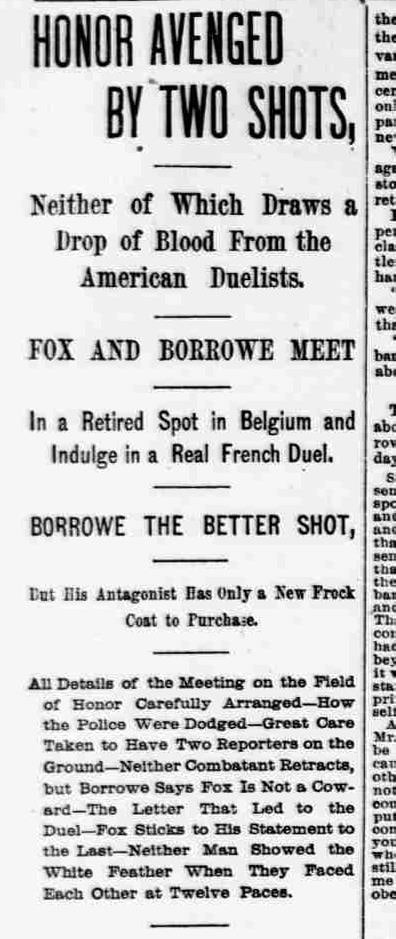

An isolated place was essential for a duel: etching of two gentlemen duelling with pistols in a woodland glade (1823).

An isolated place was essential for a duel: etching of two gentlemen duelling with pistols in a woodland glade (1823).© Wellcome Collection

Even with these difficulties, and a decline in British duelling more generally, challenges to fight in Flanders continued throughout the 19th century. Some duels were halted before the protagonists crossed the channel, as in an 1874 case in which an unnamed member of Parliament and an army officer, who had quarrelled over a lady, were arrested on the Dover-Ostend steamer carrying ‘a case of very murderous looking weapons’.

Others, more discrete, managed to elude detection. In 1850, for example, a factional quarrel in London’s burgeoning Communist movement resulted in one August Willich challenging Karl Marx to a duel. Marx declined, but one of his young followers, Conrad Schramm, contrived to take the challenge on himself. The pair travelled to Ostend, and fought near Antwerp. Schramm, who had little experience with pistols, was hit and knocked unconscious. Willich and his seconds fled the scene, while Schramm’s second looked after his friend, trying to ignore a group of haymakers nearby who might raise the alarm. When Schramm came round, they returned hastily to Ostend and the next steamer for England.

French duellists had fewer obstacles if they wanted to fight in Belgium, and a number of cases involve little more than setting foot over the border. Common locations for duels including Erquellines, Mons, Mouscron and Tournai, all easily accessible by train in the latter half of the century. Some duellists went through to Brussels, where the Bois de la Cambre was a favourite venue.

Belgium became the duelling ground of choice for French journalists

In particular, Belgium became the duelling ground of choice for French journalists, although some saw little point in going so far. ‘Fighters are not half so much interfered within the neighbourhood of Paris as they are near Brussels,’ wrote Francisque Sarcey of L’Opinion nationale. In 1863 he fought Aurélien Scholl of Le Figaro in a beetroot field near Mons, but the duel was soon interrupted by the gendarmes. They crossed swords again two days later, this time over the German border, with Sarcey taking a light wound to the arm. The story goes that both sides then retired to an inn to dine, where they learned to their horror that duelling carried the death penalty in that part of Germany.

Paris gendarmes intervene in a duel. From a drawing by Henri Dupray, in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 1887

Paris gendarmes intervene in a duel. From a drawing by Henri Dupray, in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 1887© Wikimedia Commons

One of the most incorrigible duellists in the French press was Henri Rochefort, who came to the Belgian-Dutch border to fight on at least three occasions, in 1868, 1890 and 1891. The attraction was that he could cross and recross the border, avoiding the gendarmes on either side as required. But for the later duels, he was also pursued by his colleagues in the press, who informed the gendarmes of his movements and threw other obstacles in his way. Most of all, Rochefort was worried by what they might write afterwards.

‘For many years I had been advised to take the first opportunity of looking at two magnificent paintings by Van Eyck in a church at Ghent,’ he wrote in his memoirs. ‘If I had gone to see them, all the local papers would have declared that I went into the sacred edifice to recommend my soul to God before the encounter. And I deprived myself of the pleasure of contemplating the Van Eycks.’

Duellists even came from America to fight

Duellists even came from America to fight. In 1874, a dispute between the editors of two Spanish-language newspapers published in New York ended with one of them taking a bullet in the side, in a meadow near Tournai. And in 1892, a thwarted American duellist crossed the Atlantic to demand satisfaction from his own second.

The Fox-Borrowe duel was front-page news for The Pittsburg Dispatch in 1892.

The Fox-Borrowe duel was front-page news for The Pittsburg Dispatch in 1892.The story is worth telling from the beginning. In the autumn of 1891, gossip in New York society about a love affair between Hallett Alsop Borrowe and a daughter of the wealthy Astor family had reached such a pitch that her husband, James Coleman Drayton, took the family to London for the winter. Borrowe followed, and was seen out with Mrs Drayton, so her husband summoned his rival to Paris to settle the matter. Borrowe went, but his seconds – the seasoned duellist Harry Vane Milbank and the journalist Edward Fox – refused to let him fight. They argued that Drayton had waited too long to act, and had effectively been paid by the Astors to keep quiet about the affair. In short, he had no honour to offend.

Drayton protested, but could not force Borrowe to fight. He booked a passage back to the USA, only to find mid-ocean that Borrowe and Milbank were on the same liner. Worse still, news of the frustrated duel reached the New York papers while they were at sea, and the ship was met by crowds anxious to know if the two men had managed to kill each other on-board.

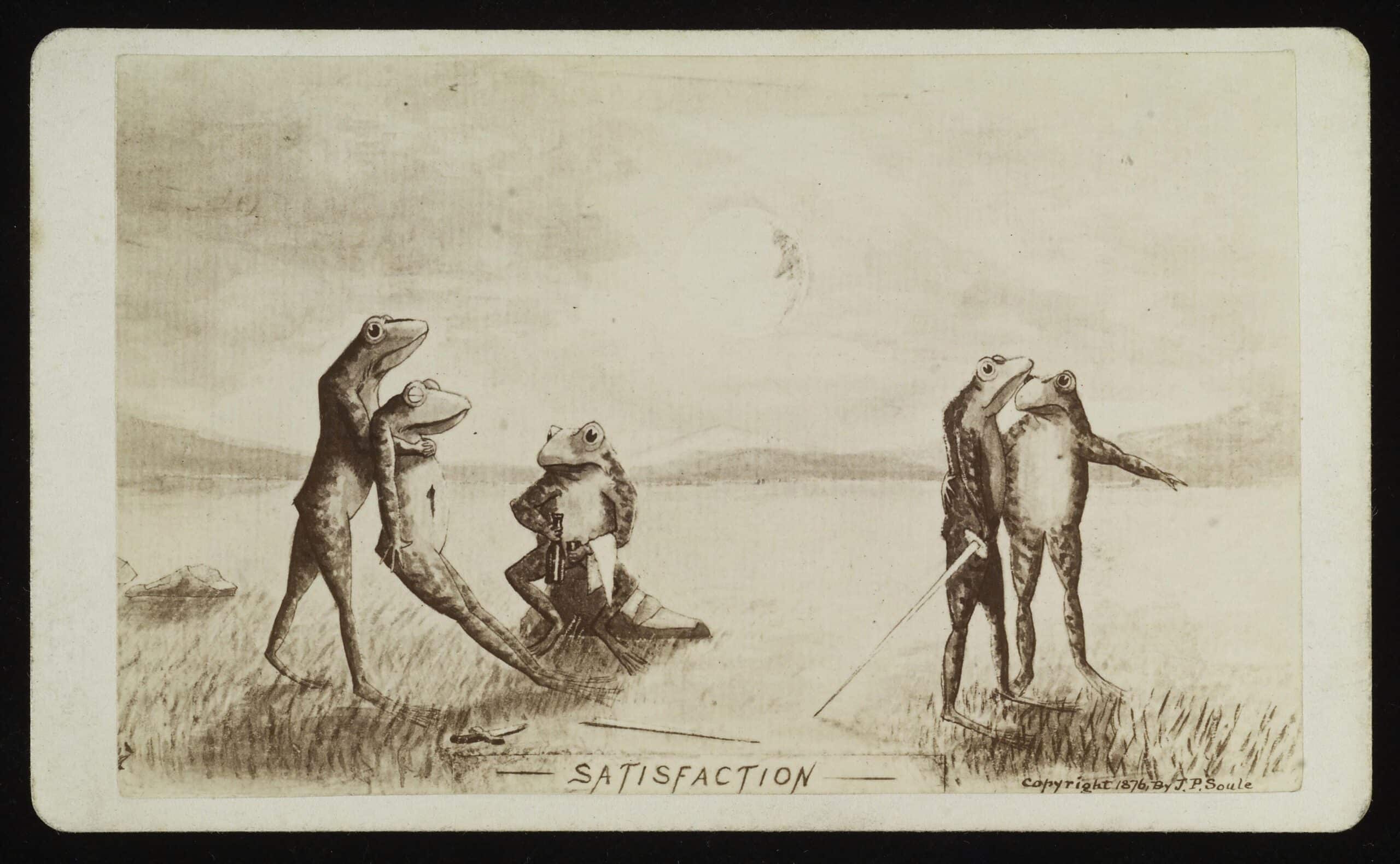

While duelling was a serious business for the participants, it was often ridiculed, as in this 1876 carte de visite photograph by John P Soule, part of a series involving frogs engaged in human activities.

While duelling was a serious business for the participants, it was often ridiculed, as in this 1876 carte de visite photograph by John P Soule, part of a series involving frogs engaged in human activities.© Wellcome Collection

This was bad for Drayton and the Astors, but Borrowe also felt compromised, since his side appeared to be the source of the story. He and Milbank knew nothing about it, so it had to be Fox. They booked another passage, back across the Atlantic, so that Borrowe could challenge Fox to a duel. He wrote to his adversary: ‘As a second you are a lamentable failure, Mr Fox; perhaps as a principal you might be a success.’

The duellists and their seconds travelled from London to Antwerp, intending to fight at a property of a wealthy expat businessman. But the local police had been alerted, and the duellists changed to the coast. They took an early train to Ostend, and then travelled by carriage to the Hotel Prévost in Nieuwpoort. They dined separately, and then ventured out into the dunes, dressed in what was then considered traditional duelling attire: top hats and frock coats. Four rounds were exchanged under a blazing sun. All missed, although one bullet cut the skirt of Fox’s frock coat. Honour satisfied, but without a reconciliation, the parties returned to London, and to America.