How the World Views Dutch and Dutch Speakers

If you’re not Dutch, you’re not much. Or: If it ain’t Dutch, it ain’t much. Anyone who has ever travelled in Canada or the USA or surfed through English language websites will recognise this proud declaration on bumpers, mugs and tee-shirts. The phrase expresses the vision of the Dutch in North America or their descendants. But does that vision correspond with how other people view the inhabitants of the Low Countries and their language? Or is the picture more nuanced?

© Etsy

To answer these questions, let’s take a look at which expressions using the words ‘Dutch’, ‘Holland’ or ‘Flemish’ exist in other languages, and which metaphorical meanings those phrases have acquired. What picture emerges about the image of the Netherlands and the Dutch language abroad? And is that image consistent across all countries?

‘Dutch’ in Great Britain

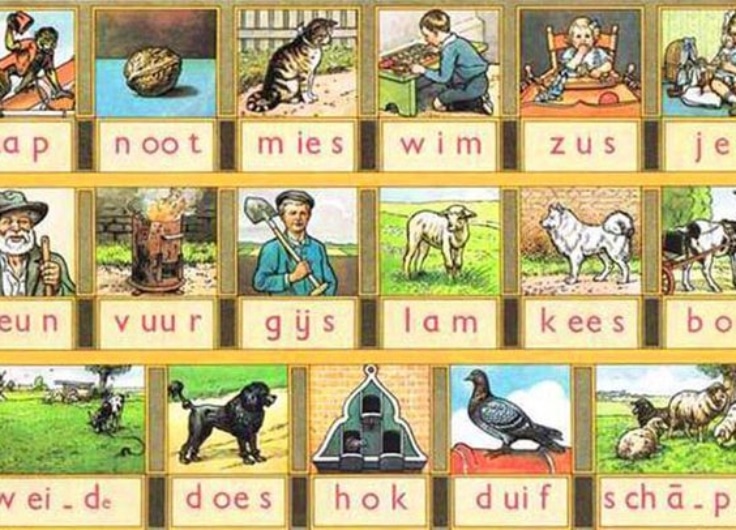

In the English-speaking world, Dutch is a household name: it occurs in a large number of expressions. These have been collected in two books: Total Dutch (1999) by Ton Spruijt and De Dutchionary, a dictionary of all that is Dutch by Gaston Dorren (2020). Many of those expressions are neutral; for example, a Dutch garden is a garden with flower beds and water features, after the Dutch example. Another group of phrases have either positive or negative connotations, from which we can infer something about the image of the Low Countries. Some of the expressions do not refer to the Netherlands but to Germany; we will of course omit them here.

If we limit ourselves to the best-known expressions that are still in use, a certain image emerges – a negative image. But that attitude is not exactly the same in Britain as it is in the US. The English emphasise an assumed predilection of the Dutch for spirits: they speak of ‘Dutch courage’ for what is called jenevermoed in Dutch, and of a ‘Dutch bargain’ for a well-oiled (drunken) bargain. The Dutch also seem to have a predilection for conversation-stopping remarks: a comment such as “thank God it’s no worse” is a typical example of ‘Dutch comfort’ or ‘Dutch consolation’. ‘Double Dutch’ refers to a gibberish that is unintelligible to the English ear but the Dutch, apparently, also have a well-developed ‘-better-safe-than-sorry mentality because nowadays ‘double Dutch’ also means having extra safe sex using two contraceptives (a condom and the pill) at the same time. The fact, according to the English, that the Dutch are not averse to sex is apparent from the name ‘Dutch cap’ for a diaphragm, and ‘Dutch wife’ for a pillow or hot water bottle in bed, but also for a sex doll.

Moreover, the English clearly distance themselves from the Dutch in the somewhat exalted expressions ‘if that’s true, then I’m a Dutchman’ (I don’t believe a word of it), ‘I’m a Dutchman if I do’ (over my dead body) and ‘If not, I ‘m a Dutchman’ (really, I swear it’s true).

‘Dutch’ in the United States

American dictionaries show that the most striking characteristic of the Dutch as far as Americans are concerned is their frugality. In America, the telling expressions ‘Dutch party’, ‘Dutch supper’, ‘Dutch treat’ and to ‘go Dutch’ have arisen. They all mean that everyone has to pay their own share; no one is treating the others.

A second characteristic of the Dutch, according to Americans, is their rudeness: they say plainly what comes to their mind (they ‘talk like a Dutch uncle’), and they often do so in an incomprehensible language (‘it’s Dutch to me’). They make a lot of noise (in American slang: ‘a Dutch concert’ or ‘Dutch medley’) and destroy everything: ‘to Dutch’ is synonymous with ‘to destroy’.

Cowardice is also associated with the Dutch: to ‘take Dutch leave’ or to ‘do the Dutch’ (act) is synonymous with deserting, but ‘do the Dutch’ is also used for the ultimate escape, namely death. To ‘get in Dutch’ means to get into disgrace or out of favour; to get into trouble. The ‘Dutch oven’ is also less clear-cut: the British simply refer to it as a heavy, cast-iron stew pan, but in American English it means breaking wind under the blanket and then pulling it up over your head!

In the United States, the Dutch are associated with frugality, rudeness and cowardice

In short, the most striking Dutch characteristics for the English are alcoholism and debauchery, and for Americans stinginess, rudeness, being loud and cowardice. Both agree that the Dutch language is incomprehensible gibberish. Fortunately, there is also something positive to report about the Dutch. According to Americans, the Dutch are not easily upset or dismayed. ‘That beasts the Dutch’ means that something is astonishing – ‘well, that beats everything.’

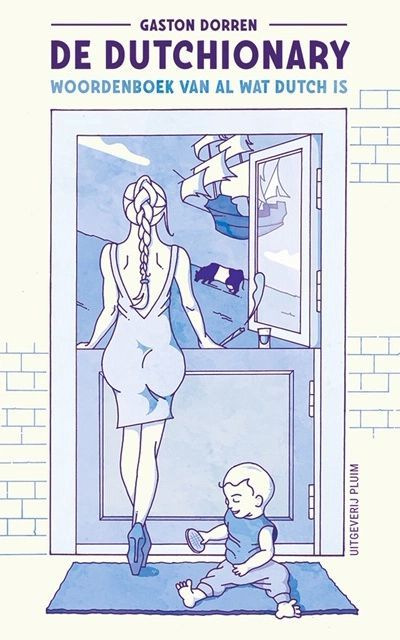

Modern stereotypes: 'clog wogs' and 'wooden'

Expressions related to the Dutch and their language have been used in English for a long time and stem from historical competition between the British and Dutch. But what is the situation now, what image do modern English speakers have of the Netherlands and Dutch? To find out, I conducted a survey in 2019 among a large group of Dutch and Flemish emigrants. One of the questions was about the jokes or stereotypes about Dutch and Flemish people in the new country of residence.

The answers from the English-speaking world are quite uniform and clichéd, confirming the information in dictionaries: the most common characteristic of the Dutch is their frugality. Also often mentioned are directness, rudeness and arrogance. That directness is, however, also seen as a positive characteristic: ‘You know where you’re at with the Dutch. They can be bloody rude, but they speak their mind.’ In New Zealand they say: ‘The Dutch are too honest to be polite. Kiwis are too polite to be honest.’

A Dutch couple in traditional costume from Volendam. Note the clogs.

A Dutch couple in traditional costume from Volendam. Note the clogs.Yet there are also clear differences within the Anglophone world. For example, Dutch immigrants in Australia are mockingly called ‘clog wogs’ – a rhyming phrase based on clog (clog) and wog (‘worthy-Oriental-gentleman’ or foreigner, immigrant). Additionally, in Australia, puns are made with the word dike, which is slang for the toilet in Australian English. This gives an ambiguous meaning to the sentence ‘he put his finger in the dike’, alluding to the children’s book about Hansje Brinker who stopped a flood with his finger. They also say mockingly that the Dutch ‘swim in dikes’.

In Canada, the supposed stubbornness of the Dutch and the association with clogs has led to original puns: ‘Those Dutch with their wooden shoes, wooden bridges and wooden houses. The problem is that they wouldn’t listen’ and ‘Wooden shoes, wooden head, wouldn’t/wooden listen’.

In Britain another riddle was mentioned: ‘What is the likeness between a sensible Dutchman and God?’ Answer: ‘No one has ever seen either.’ In Ireland it is said: ‘If the Dutch lived in Ireland, they would all be millionaires; if the Irish were living in the Netherlands, they would all drown.’ This refers to the frugality and height of the Dutch.

Hollands and Flemish

Outside of the Anglophone world, the Dutch have left fewer linguistic traces. If we look at dictionaries of other languages, we find hardly any expressions or humour relating to Dutch, Hollands or Flemish. However, the actual words Dutch and Flemish (not Hollands as far as I can see) have sometimes acquired a specific meaning for an object or animal that, at least originally, had a special connection with the Low Countries. In French, for example, une hollandaise is used for a certain type of Dutch cow, and hollande stands for a Dutch cheesecloth made of fine linen, porcelain from Holland, a variety of apples and woven, vellum paper. A fine Dutch weave of cloth is also known in English as ‘Holland cloth’ and in Spanish and Portuguese as holanda. In Spanish, holanda also denotes a type of brandy.

In German, Holländer stands for, among other things, a paper mill, a certain type of cheese and a type of windmill. The Danish Hollænder includes a Dutch vessel, a machine in a paper factory, a type of bread and a type of cheese. In Polish, holender and holenderka indicate a Lakenvelder (type of) cow, a breed of chicken, a specific skate design, a Dutch windmill, a mixing trough in a paper mill and a certain type of roof tile. In Czech, holand denotes a fine type of paper, while holanďanka/holandka is a breed of chicken. In Russian, a gollandka is also a type of chicken, a type of cow, a tile stove and, in the past, also green cabbage or kale and a sailor’s shirt, while gollander denotes the mixing trough in a paper factory.

In some languages the word Flemish also refers to animals and items originating in the Low Countries: in one Romanian dialect felendreş stands for fine fabric from Flanders; in English, ‘Flanders’ was a prized type of lace and also a Belgian draft horse. In Lithuanian, flandrai denotes a species of rabbit that is called the ‘Flemish Giant’ in English.

The Flemish Giant

The Flemish Giant© MichellesVlaamsereuzen

This list is certainly not complete, and some words and meanings are archaic or only used in dialects, but the tone is clear: Dutch and Flemish refer to typical Dutch and Flemish products; particularly cheese, cows, chickens and linen.

I didn’t find many positive metaphorical expressions; only negative ones, and only in German and a specific Russian dialect. In German, nen Holländer machen means ‘to clean one’s plate’, durchgehen or losgehen wie ein Holländer mean to ‘run away’ and to ‘know how to get out of it’. In German dialect Flämsch means ‘unfriendly, angry, rude’. Finally, in Russian underworld slang, nesti Gollandiju

– which literally translates to ‘tell Dutchies’ – means to talk out the side of your mouth, telling only a version of the truth.

Frugal and stingy

Dutch and Flemish emigrants report that jokes are made about Dutch frugality and stinginess in most foreign countries. We find this usage from France, Germany, Greece and Hungary to Israel, Morocco, Turkey, South Africa, Argentina and Brazil. Everywhere, jokes are told about the frugal Dutchman. The most commonly mentioned are:

How did copper wire originate? By two Dutchmen fighting over a coin.

How can you get 20 Dutchmen in the back of the car? Throw 10 cents in the trunk.

How do you know that you are in the Netherlands? Toilet paper hangs to dry on the clothesline.

Why do the Dutch tell Belgian jokes? Because they cost nothing.

When do you see a Dutchman running? When a penny rolls down the street.

Why does a Dutchman have such large nostrils? Air is free!

How do most recipes in a Dutch cookbook start? First, borrow an egg…

On the Swedish island of Tjörn, there is a proverb: Det flyger inga måsar bakom Holländska båtar or ‘seagulls never fly behind Dutch boats’ (because they never throw anything overboard). In Italy it is said that the Dutch person always has braccia corte (short arms), which means that he cannot reach his wallet. And in Brazil, a joke is told about a party where everyone – American, Scots, French… – brings something. The Dutchman does not bring any food or drink, but instead… an extra guest!

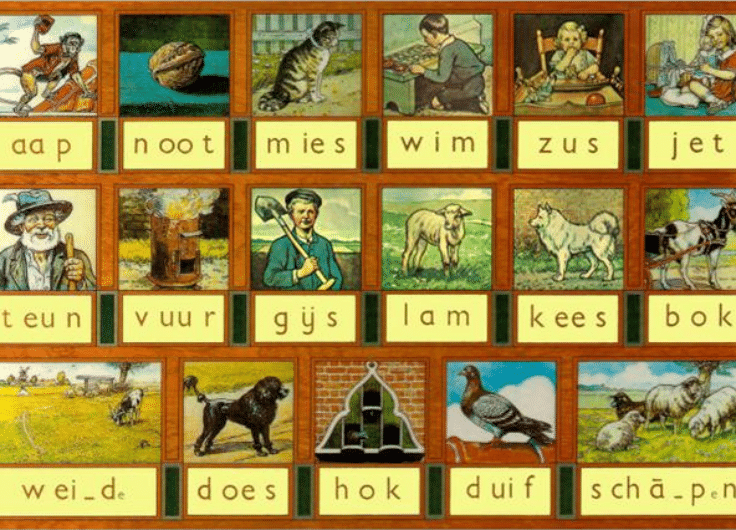

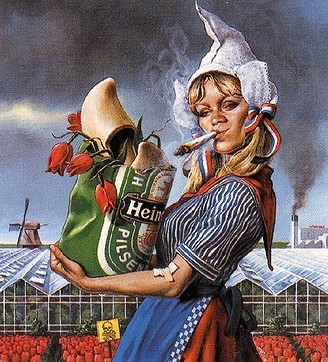

A lot of stereotypes about the Dutch in one image

A lot of stereotypes about the Dutch in one imageJokes about the Dutch people’s liberal views concerning sex and drugs are also common. In Portugal, people know the riddle: ‘What is the similarity between Amsterdam and the Tour de France?’ Answer: ‘Drug users on bicycles.’ The Dutch are known everywhere as ‘cheese heads’, and in Spain they warn the Dutch to be careful not to melt in the Spanish sun.

So much for the similarities. But there are also clear differences: in some linguistic regions certain Dutch characteristics are emphasised more than elsewhere.

A lack of refinement

The French, who, as we know, attach great value to a refined cuisine and fashionable, elegant clothing appear to be shocked by the poor quality of Dutch cuisine, by the fact that the Dutch take food (or, more specifically, potatoes) in their cars and caravans on holiday, and wear white socks with sandals. In Spain and Portugal, the Dutch custom of eating cheese sandwiches for lunch is viewed with disgust. In Switzerland the riddle exists: ‘Do you know that story about Dutch cuisine? No? Exactly.’

Driving and football

The German-speaking world seems to be particularly annoyed by the Dutch driving style. Many jokes and riddles refer to the yellow colour of the Dutch number plates: ‘When do you get a yellow number plate for your car? When you have failed your driving test three times!’ And also: ‘Once you fail your driving test, you get a yellow number plate. If you fail again, you get a caravan behind your car.’

Those yellow number plates are legendary in Spain, too, where they speak of lava amarilla or slow-flowing ‘yellow lava’: that is to say, the yellow number plates that populate the roads in summer and are the only ones to respect the speed limit, thereby holding up traffic.

Meanwhile, back in Germany, they say that for every traffic jam there is a Dutchman driving a caravan, and usually doing so in the left lane of the Autobahn! Hence the joke: ‘What does NL mean?’ Answer: Nur Left (Left only).

In international football competitions, the Netherlands and Germany have traditionally been important and threatening competitors. All kinds of jokes are told in both countries to neutralise the threat. The legendary Dutch loss in 1974 naturally led to a certain amount of Schadenfreude

in Germany. Hence the riddle ‘What does a Dutchman do after his football team has won the World Cup? He turns off his PlayStation and goes to bed.’ In 2008, the similarity in colour (orange) between the shirt of the Dutch national team and the garbage cans in Berlin inspired the German easy listening singer Mickie Krause to sing along to Orange trägt nur die Müllabfuhr or ‘Orange is only suited to garbage collection’.

Finally, Germans like to joke about one of the most important Dutch exports to Germany, greenhouse tomatoes, which are too hard, too pale and, above all, too watery, hence the riddle ‘What is the difference between Jesus and a Dutchman? Answer: ‘Jesus turned water into wine, Dutchmen turn water into tomatoes.’ And of course, the otherwise apocryphal statement of the German poet Heinrich Heine is often quoted to mock the alleged slowness of the Dutch: ‘When the world ends, go to the Netherlands, everything happens there fifty years later.’

A disease of the throat

In the Scandinavian languages, Dutch stands out mainly because of its sound. All kinds of jokes are made about the many g and r sounds, so that anyone speaking Dutch is said to sound like he has a throat disease and imitated with a lot of “chagachagocho”, while people say derisively: ‘I am not possessed by the devil, I am speaking Dutch.’

In Denmark, the satirical TV program Drengene fra Angora (The Boys from Angora) has been on the air since 2004. The very popular program includes skits by a team of amateur cyclists, Team Easy On. One of those riders is Pim de Keysergracht, who does not speak Danish, but English, and with a remarkably hard g – to which his name lends itself well. He experiences all the prejudices about Dutch people: he grew up in the Amsterdam red light district, his mother is a prostitute, he has blue hair, is bisexual and uses drugs and doping. Dutch tourists in Denmark owe the caricature of a Dutch weed-smoking cyclist to Pim de Keysergracht.

Good-natured

The examples show that there is no unambiguous picture of the Netherlands and the Dutch abroad; the only point of consensus concerns Dutch frugality. That the image differs depending on language is, of course, because Dutch idiosyncrasies are weighted differently in different countries. In Burgundian countries such as France, Dutch cuisine is disparaged whereas, in a country like Germany, where the motorways are free of speed limits, people are amazed by the careful Dutch driving style. In fact, the jokes and stereotypes say more about other countries than about the Netherlands.

The positive stereotypes are heavily outnumbered by the negative, but the negative are really no more than good-natured teasing

The positive stereotypes are heavily outnumbered by the negative, but the negative are really no more than good-natured teasing, sometimes combined with admiration for the efficiency and hard work of the Dutch. For example, a Dutch immigrant in Denmark reports that it is said there that the Dutch never sleep or, if they lie in bed, they keep their clogs on (!), so they don’t have to get dressed when they wake up in the morning and can work even harder.

Incidentally, the image of the Belgians appears to be more positive than that of the Dutch. For example, someone in Austria was heard to say: ‘No problem on your hands with a Belgian, nothing in your hands with a Dutchman.’ And, in Sweden, an emigrant heard the – by the way, not original – riddle ‘What is the difference between the Dutch and the Belgians?’ Answer: ‘Put two Belgians together and you have a party; put two Dutch people together and you have a working group.’

This article was realised with the support of the Nederlandse Taalunie (Dutch Language Union).