The Dutch And Flemish Canon: Stuck Within National Frameworks

Historian Rolf Falter compares the attempt of the Flemish Government to formulate a so-called historical canon – a list of what is essential to remember of history – to a similar attempt in the Netherlands. He concludes that both canons are a collection of standalone stories, whereby contemporary political sensibilities and, above all, a still quite nationalistic approach have influenced the selection of the subjects. Is it then – already deep into the 21st

century – still so difficult to view histories from a broader perspective – Lowlands, European and international?

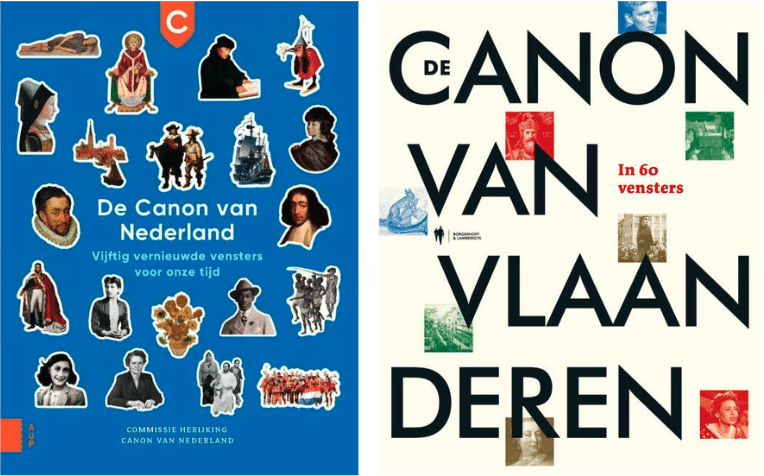

On 9 May 2023, in a former mining building in the city of Genk, the Government of Flanders and a panel of historians presented the first-ever attempt to formulate a so-called historical canon, a more or less official list of what is essential to remember in the history of Flanders. Their effort was inspired by the Canon of the Netherlands, created seventeen years ago and updated in 2020.

In this article, I will not delve into the polemics that both canons raised. Nor will I question the sense or nonsense of making a canon per se. What I will do is discuss the content of these canons, especially by extensive comparison. For this, I will use the updated version of the Canon of the Netherlands of 2020.

Before I begin, I should note that both the Dutch and the Flemish Canon committees have emphasized the relativity of their undertaking. Both assume that in twenty or even ten years, revisions of the themes – so-called ‘windows’ on each historic subject – will necessarily appear. In its most recent iteration, the Dutch Canon saw ten new windows introduced out of a total of fifty that had been proposed in 2005.

The book covers of the most recent Canon of the Netherlands (2020) and the Canon of Flanders (2023)

The book covers of the most recent Canon of the Netherlands (2020) and the Canon of Flanders (2023)Olla vogala

Both canons explicitly designate “culture and history” as their fields of interest. In the Dutch Canon, this is defined by the adjective “Dutch”, while the Flemish one eschews further description. However, the Flemish Minister of Education, Ben Weyts (of the Flemish nationalist party N-VA, the largest political party in Belgium) did specify in Genk that the canon must represent everything that “has made Flanders and made us a Flemish people”. So, what does that yield, era by era?

Until the year 1000 AD, there was nothing to suggest that the distinct regions of the Netherlands and Flanders (or Belgium for that part) would eventually emerge. Even the County of Flanders, which originated around the year 850, is a different geographical entity than the Flanders of today, the one that produces this canon.

Still, there are two important events from this period. The first one was the razing in the years 58-51 BC of the whole of Gaul by Julius Caesar and the Romans, who were above all in search of booty. Then, in the eighth century, there was a quite mysterious shift of the centre of power from the south of Gaul to the north. That happened when the Frankish-Merovingian dynasty was overthrown by its hofmeiers

(stewards of the royal domain) from the Haspengouw region in present Belgium, who created the so-called Carolingian dynasty.

How is this period before 1000 AD represented in each of our canons? It is explained in six windows in Flanders, and five in the Netherlands. These offer almost the same themes – the nomads, then the farmers of prehistoric times, then the Roman invasion and the Frankish Kings – but each canon has chosen a location inside the present borders of its territory (present-day Flanders and the Netherlands respectively) to illustrate those periods of the past.

Tongeren firmly anchors the Roman period in the Flemish Canon, while the Limes border and defence zone of the Roman Empire on the borders of the old Rhine finds its place in the Dutch one. If you read both canons on the Roman period you might get the impression that it was quite a distinct story in the areas of what is present-day Flanders and present-day Netherlands. Of course, it was not.

One of the sixty windows of the Flemish Canon is the Mechelen Choir Book. This illuminated musical manuscript from the sixteenth century was once part of the art collection of Margaret of Austria.

One of the sixty windows of the Flemish Canon is the Mechelen Choir Book. This illuminated musical manuscript from the sixteenth century was once part of the art collection of Margaret of Austria.© Sophie Nuytten - Museum Hof van Busleyden

It is interesting to note that all four locations mentioned in the Flemish Canon fall just within the border of modern-day Flanders. Also the once so Calvinist Netherlands has dedicated an entire window to Saint-Willibrordus in its canon, whereas the once so Catholic Flanders gives barely a sentence over to the Saints Eligius and Amandus who Christianized the areas later known as Flanders, Brabant and Loon. Both canons then dedicate an entire window to the Roman Emperor Charlemagne. In the Netherlands, the content of that window is slightly more up-to-date than in the Flemish version.

On to the High and the Late Middle Ages, and the birth of what we call today the Western European civilization, in which the Low Countries played a quite important role. The Dutch Canon has just two (2!) windows on offer: one rather original and well-deserved, on the cooperating merchants of the Hanseatic League in the cities around the IJssel, and one for hebban olla vogala. That latter one is a piece of handwritten text of two lines, found in a manuscript from Oxford, that might be the first known words of the Dutch language.

Hebban olla vogala also opens the Flemish series, which dedicates ten (10!) windows to the whole period. They include agricultural innovation, the ports of the Zwin near Bruges, the major cities of the county of Flanders (seen through the eyes of an Arab cartographer), the literary masterpiece Reynard the Fox, the epic battle of the Golden Spurs of 1302, and the Ghent Altarpiece of Jan Van Eyck. All windows taken together suggest that in those centuries a remarkably high level of civilization was achieved, but there is no further exploration on that item.

Spoiled for choice

This brings us to the period from 1450 to 1650, that of the Burgundian and Habsburg Netherlands, for which we might expect a more common narrative across the two canons. But no: only the globetrotter Erasmus appears in a window in both canons. The Flemish Canon rushes on in only seven windows over the period up to the rampaging Sun King of the end of the seventeenth century.

Four of these windows are purely cultural: polyphony, Bruegel, Rubens and the scientist Simon Stevin. The other three are the burning of witches, a Flemish monk who happened to travel to the Aztec Empire with the Spanish conqueror Cortes (where he denounced the brutalities he encountered there) and, indeed, the Iconoclastic Fury of 1566 in the Low Countries. The latter is the only mention of the Revolt against Philip II, King of Spain. For William of Orange, – in fact, Guillaume d’Orange, the French-speaking nobleman who spent a great deal of his life in a Brussels palace – two sentences and a modest portrait should satisfy the curiosity of the readers.

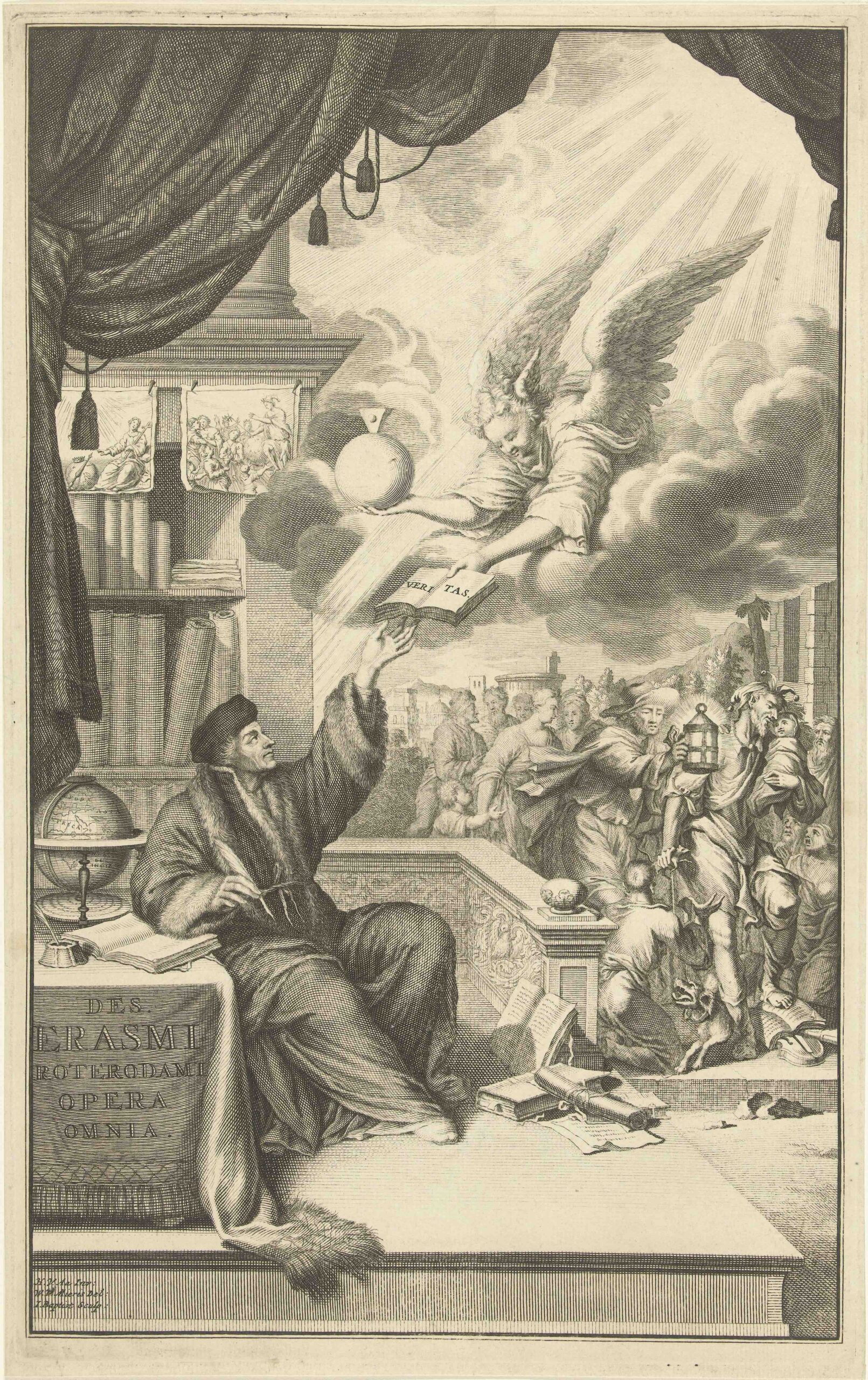

For the Burgundian and Habsburg Netherlands, you would expect a common narrative. But only Erasmus gets a similar window in both canons.

For the Burgundian and Habsburg Netherlands, you would expect a common narrative. But only Erasmus gets a similar window in both canons.© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Dutch Canon on the other hand is developing a total of twelve windows, besides the one for Erasmus. Ten are primeval classics of Dutch national history: from William of Orange to the Dutch East-India Company, and the States Bible to the legendary admiral Michiel de Ruyter. The window for Mary, the Duchess of Burgundy for only five years, is a surprising choice. Of course, she was the only woman ever to rule all of the Low Countries, but we do not know the extent to which she was independently assertive in that role. The final window is about the Beemster, as a starting point for the unique phenomenon of poldering, or land reclamation.

After 1650, both canons rush into modern times. In Flanders this happens in two windows – the bombardment of Brussels by Louis XIV in 1695, and the distant Empress Maria Theresia, who never actually set foot in the Austrian Netherlands. Meanwhile in the Netherlands, after two more offshoots of the Golden Age (Huygens, Spinoza), three windows help us make the leap to modernity: slavery, of course (in its heyday, the Dutch Republic was the first to turn people into commodities), the planetarium of eighteenth-century Frisian businessman Eise Eisinga, and the Historie van mejuffrouw Sara Burgerhart, the 1782 moralizing novel by Betje Wolff and Aagje Deken who are presented as emancipated women in what is considered the Dutch version of the Enlightenment. After which, in both canons, approximately half of the windows remain to cover the most recent 250 years.

Similar choices

This is where a comparison is no longer so useful, because, from 1830 onwards, two distinct states emerged, even if the Flemish federated state within the new Belgium was then only an idea in its infancy. Yet it is striking that for precisely the last two centuries, both canons make for the larger part similar choices: the domination of Bonaparte, the writing of a modern constitution, the first railway line, the emancipation of women, some literary celebrities, the deportation and genocide of tens of thousands of Jews (represented by the Dossin barracks in Flanders and by Anne Frank in the Netherlands), our inability to abandon the colonies in a decent way (each canon features a hitherto unknown intellectual from the colonies who had resisted occupation), the arrival of television, the development of the European Union, and immigration.

Still, there are differences. Some can be chalked up to subjective choice by the committees. Flanders considers the arrival of the machine and the Industrial Revolution (in Ghent) worth a separate window, and also the struggle for voting rights, the rise of the welfare state, and the invention of the anti-conception pill. The Netherlands chooses the turmoil of the so-called Patriots era in the 1780s, the reign of King William I, the legislation banning child labour from the end of the nineteenth century, and the development of the port of Rotterdam.

Some of the differences are just logical: the Flemish Canon includes the Flemish emancipation struggle (including the enthusiastic collaboration of the Flemish Movement with the Nazis), while the Dutch one includes the North Sea flood of February 1953 that killed more than 1,500 people and, the failure of a Dutch United Nations Peace Corps in Srebrenica in the Yugoslav War in 1995.

Finally, both canons make some inclusions to please the media and the wider public: Flanders chooses to mention Rock Werchter festival, the very popular Farmers’ Union cookbook, and the cycling race Tour of Flanders, while the Netherlands has chosen to include a little tourist hatch in every window.

Dutch Language Union

An analogy that can be made to describe both canons – even more when you have compared both– is that of l’Auberge Espagnole: the house will serve you what you bring in yourself. The consumer can count upon the inn’s four walls – the political starting point. It’s a reasonable space, it does not harm, and it even invites you to start a polite discussion or – if you’ve just eaten a bad meal – perhaps a few nagging complaints.

But has the project demonstrated why it could be essential that our children learn about history, let alone why we as adults should be interested in it? Not really. Both canons are too loosely compiled, composed of granules of sand, a collective work by a panel that is as venerable as it is heterogeneous. They inevitably avoided a baseline, because of course the panel must respect diversity and treat each opinion in proportion to its popular impact. This is not unexpected at a time when many historians – including myself – see history as a chain of coincidences, any consistencies emerging only by chance.

Have these canons contributed to our identities? The strange thing about both exercises is that they arose from the feeling that we had become somewhat insecure about our (real or supposed) identities – the Netherlands in the wake of the murder of the popular and populist new politician Pim Fortuyn in 2002, and Flanders after a decade of flaring nationalism. But as soon as the canons neared completion, their creators in both the Netherlands and Flanders passionately denied it was ever the intention to use history to define identity.

This too is not wholly unexpected: many new political movements – often described scornfully as “populist” – ride the rhetoric train of identity to connect with voters’ deep frustrations about out-of-control globalization. But as soon as they gain power, they divert that train to an abandoned railyard, no doubt out of realism. Not even the crazed Donald Trump could escape this inevitability during his first term.

The strange thing about both canons is that they arose from the feeling that we had become somewhat insecure about our (real or supposed) identities

Considering this, has either canon paid enough attention to the international environment, or the influence of Europe and the rest of the world on our past? Again, the answer is: yes, but only fragmentarily. The Romans, Charlemagne, Erasmus, Napoleon, the world wars, the EU… they are all touched upon. Although they are admittedly framed in the context of the contemporary state, there is clearly some desire to escape this tendency. This brings us to the ultimate question: is the perspective of the contemporary state far too obvious in the choice of windows, and in the descriptions within them?

The answer to this is still, unfortunately: yes. This overview has made clear the extent to which people try to draw connections between past events and the contemporary territory. This pitfall is an inevitable risk when drawing up a canon. You begin with the contemporary political context and endeavour to explain how it came to be. But in doing so, you risk implying that it has always existed. The reality of course is that on the timeline of the two thousand years of written history about this corner of Europe, the existence of a Dutch state comprises not even twenty percent, of the region of Flanders only two and a half.

On the timeline of the two thousand years of written history, the existence of a Dutch state comprises not even twenty percent, of the region of Flanders only two and a half

That contemporary political starting point can certainly be defended when we look at recent centuries, but it also leads to grievous distortions about the older past. The painting tradition of the Low Countries, for example, is widely considered to be world heritage. It is a shared tradition of both Flanders and the Netherlands – even if the epicentre shifted from Bruges and Ghent in the medieval County of Flanders, to Brussels and Antwerp in the Duchy of Brabant, to Delft, Amsterdam and Haarlem in the Dutch Republic.

Yet the Flemish Canon claims Van Eyck, Bruegel and Rubens for its history, while the Dutch claims Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Van Gogh. No painter is shared, and the links between their arts are absent. And sure, we share a single Taalunie (Dutch Language Union), an agreement to recognize the same grammar and orthography, but judging by the canons, we no longer share a joint literary history – except for hebban olla vogala (and all the unknowns that surround it).

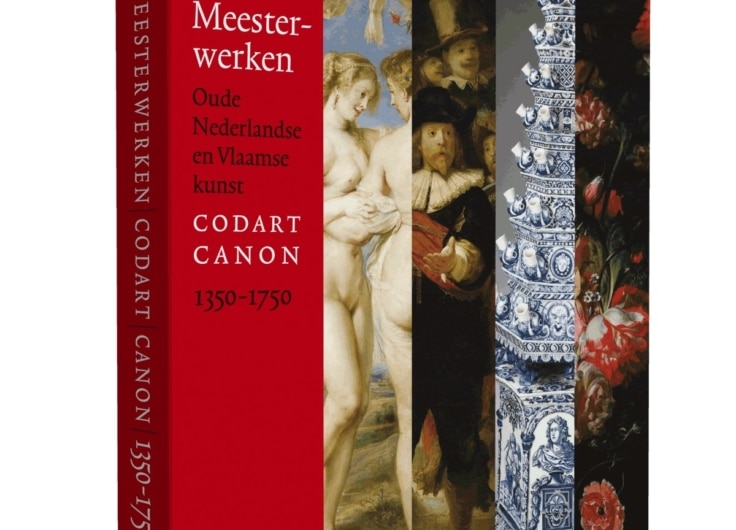

The Flemish Canon claims Van Eyck, Bruegel and Rubens for its history, while the Dutch claims Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Van Gogh. No painter is shared, and the links between their arts are absent.

The Flemish Canon claims Van Eyck, Bruegel and Rubens for its history, while the Dutch claims Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Van Gogh. No painter is shared, and the links between their arts are absent.© Public domain / Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The hammer

It has already been suggested that a multitude of canons should be produced so that the rigid choices stemming from the contemporary political perspective might be further softened. The Dutch Canon already does this, with cheerful partial canons for every province. I undertook the exercise myself, exploring what a Belgian canon might look like. I suspect that French-speaking Belgians would mainly want to add the epic story of medieval Liège, the industrial revolution in Verviers, Hergé as the father of European comics, the Battle of the Bulge around Bastogne in 1944, and the mining disaster which killed more than two hundred Italian immigrants in Marcinelle near Charleroi in 1956.

Flemings are, after all, an essential part of Belgium. Maurice Maeterlinck, the only Belgian winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, might become a head breaker: a native of Ghent who, around the year 1900, wrote in French and often lived in France, but, like Georges Simenon and Jacques Brel, occasionally turned to his Flemish homeland in his work. In the Flemish Canon, he was given one sentence and one image.

In the end, canons mainly turn out to be a collection of separate historical stories. This was also the case for the recent TV series Het verhaal van…, both also with a Dutch and a Flemish scenario. Four decades ago the second edition of the prestigious Algemene Geschiedenis der Nederlanden already suffered from this problem.

A historical synthesis that grabs you by the collar and proves the usefulness of knowing the past has not yet been delivered. And so questions arise that could make our past so much more fascinating than those that arise from the perspective of the contemporary political context.

Judging by the canons, Flanders and the Netherlands no longer share a joint literary history

How could three – and not one or four, say – smaller states emerge and above all survive between France, Germany and Great Britain, which were absolute world powers only a century ago? Why does the Dutch language area (including the former part of Northern France) coincide almost entirely with the land mass that rises to fifty meters above sea level? Why did the history of the Low Countries before the year 1000 mainly take place around the higher lands around the Sambre and Meuse, and afterwards just as exclusively in the provinces by the sea?

Why were the Low Countries at the forefront of flourishing Western civilization for half a millennium – albeit in succession: from Flanders to Brabant, and finally Holland (and why was this status lost after 1700)? Why do we belong to the privileged part of the world that developed wealth early on and continues to hold a disproportionate share of it? Why do Europe’s typically nation-forming fault lines – religion and language – in the case of the Low Countries cut straight across two nations (the religious line along the Great Rivers in the Netherlands, and the language border horizontally across Belgium)?

The English edition of the Canon of Flanders

The English edition of the Canon of Flanders© Sophie Nuytten - Museum Hof van Busleyden

There is still so much of our history to explore. And even more to deconstruct in terms of patriotic stupor. Although we have come a long way since 1900, when both the Netherlands and Belgium could not have been created but by the Creator himself, there’s still some destruction of old frameworks of thinking to be done. The hammer on old nationalistic stereotypes must still be raised, at least as much as during the Iconoclastic Fury and French Revolution taken together.

The Canon of Flanders in 60 windows, Borgerhoff & Lamberigts, Ghent, 2024, 320 pages

Open vensters voor onze tijd. De Canon van Nederland herijkt, Amsterdam University Press, 2020, 168 pages (Dutch edition)

The English edition of the Canon of the Netherlands is available online.