Dutch and Flemish Studies in Michigan: From 70 to 190 Students

The Dutch department at the University of Michigan is celebrating its 50th anniversary. By linking the course to contemporary and relevant issues, Dutch and Flemish Studies is now more in demand than ever.

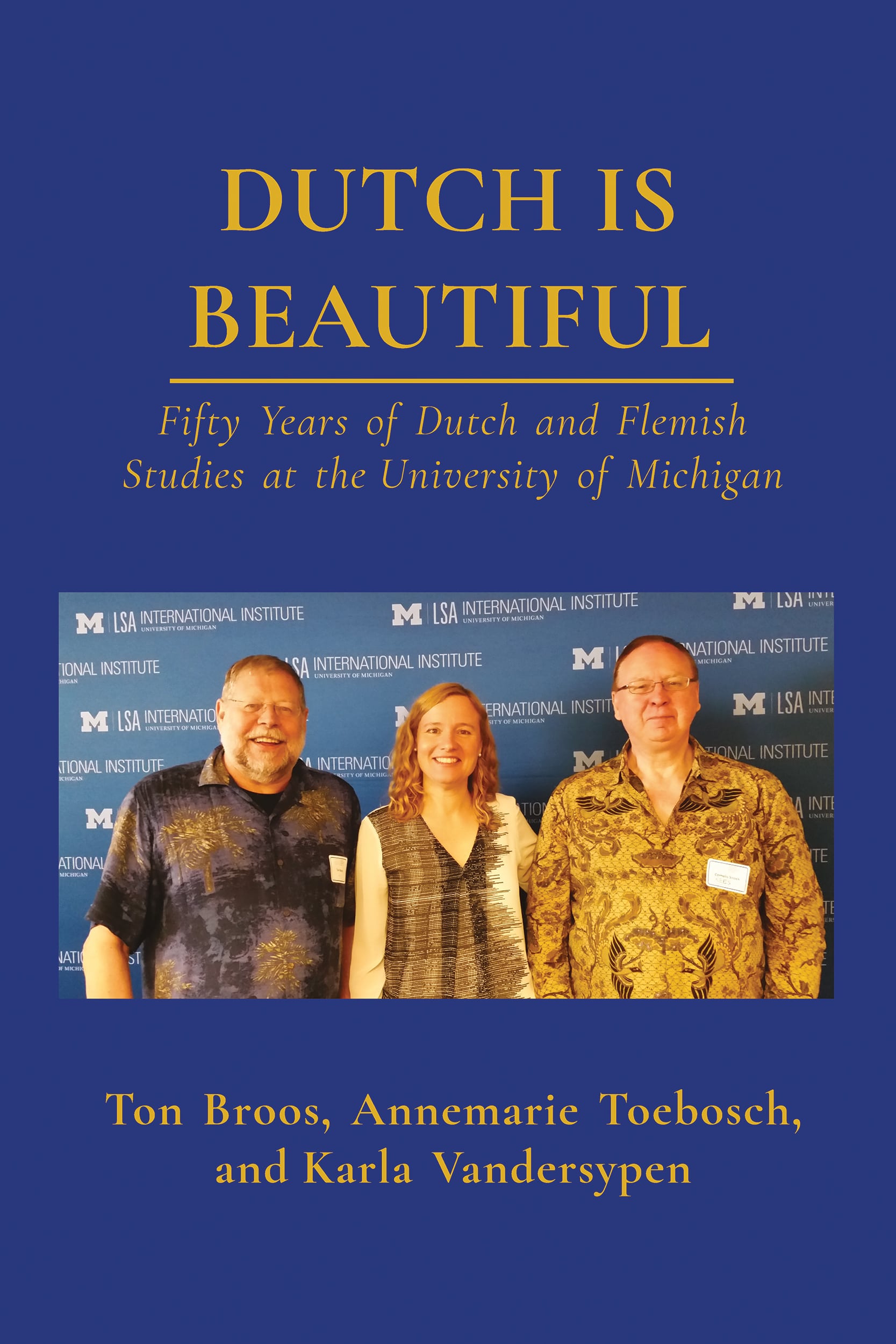

In any case, there is the book. The Department of Dutch and Flemish Studies at the University of Michigan wanted to celebrate its 50th anniversary with a semester of special events. Three events with a total of six speakers had been programmed for the autumn. Coronavirus forced the head of department, Annemarie Toebosch, to postpone these by a semester, possibly longer. ‘That’s why I’m so glad we made a book. At least we have that’, she sighs.

Dutch is Beautiful: Fifty Years of Dutch and Flemish Studies at the University of Michigan opens with a keynote lecture given by Ton Broos – Toebosch’s predecessor – about the first Dutch language and culture courses, the highs and lows of the department in Ann Arbor and the scope for the future. His story is complemented with testimonials from alumni, publication lists and some overviews, for example of the 18 Dutch writers-in-residence the university welcomed between 1981 (Bert Schierbeek) and 2005 (Henk van Woerden).

In the past half century, the book tells us, the chance requirement to teach Dutch of one graduate student has steadily grown into a fully-fledged academic department. On offer is an intensive four-semester language course of four hours per week, as well as a broad spectrum of culture courses, including one on Anne Frank set up in 1993 – now called Anne Frank in Context – that focuses on social justice and human rights and has become increasingly popular.

An additional lecturer

There is true cause for celebration. Particularly since Toebosch became head in 2012, the department is attracting much more interest: from about 70 enrollments per year then to about 190 now. This has enabled the department to expand. In the past academic year, a colleague from Flanders was able to join via Fulbright Belgium, who among other things presents a lecture series on Flemish culture. There are now four people on the payroll, including two graduate students.

Dutch is still what they call an LCTL here: a Less Commonly Taught Language

‘The survival of the department has never really been up for discussion in the past fifty years,’ says Toebosch. ‘This is not because of the descendants of Dutch immigrants in Michigan. They mainly live in the West of the state, about two hours’ drive away. Although you do always have a student with such a background. Thanks to the growth in demand, Dutch and Flemish Studies is now in the middle bracket. Although Dutch is still what they call an LCTL here: a Less Commonly Taught Language.’

Not a goal in itself, but an instrument

The secret of its success is how the department has aligned itself with the broader aims that students have for their studies. ‘That requires a different way of thinking. You should not start from the question: what is interesting about Dutch? But: how can your students learn about the world? The study of Dutch is no longer the only objective, but a tool for learning something about social justice through the lens of a culture other than their own, for example.’

A subject like decolonization, which is close to Toebosch’s heart, is uniquely suited to such an approach. It is a good fit with the Netherlands, its colonial past and its debates on tolerance and multiculturalism over the past decades. And it ties in with topics that are very much alive in America, and certainly also felt by students in Ann Arbor. ‘In this way, students not only learn about another country and culture, but also through that different way of looking learn something about themselves. They gain perspective on the colonial history of America.’

Angell Hall on Central Campus at the University of Michigan

Angell Hall on Central Campus at the University of Michigan© Wikipedia

Word of mouth

To make this a success, Toebosch sought out various partnerships. In the first instance with other programs that address similar themes; Anne Frank in Context is organized together with Judaic Studies. Toebosch also sought out smaller student communities within the huge campus. For example: the athletes or participants of the Michigan Community Scholars Program, whose members know each other very well because they usually live together.

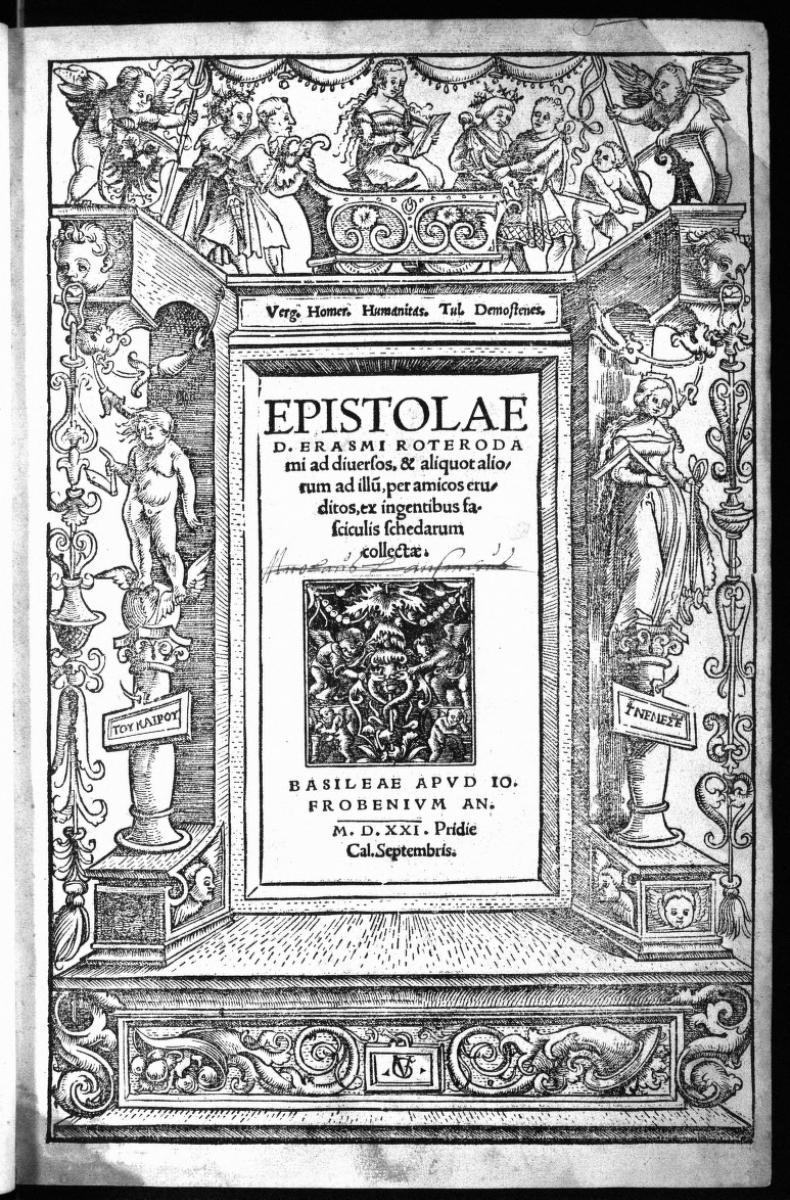

The University of Michigan Library owns a collection of rare Netherlandic books and manuscripts

The University of Michigan Library owns a collection of rare Netherlandic books and manuscripts‘The students have to take all kinds of compulsory subjects,’ she explains. ‘They have to take a course on race and ethnicity, for example. We have several courses that are eligible. When you are known to certain university communities, news that ours are interesting will travel by word of mouth. And the culture courses lead on to the language courses. Students must also take a foreign language for four semesters. Those who already know about us sometimes choose Dutch. Few students would otherwise take Dutch.’

Academic activism

The change in approach is at the expense of the more traditional focus on language, literature, and culture of departments of Dutch Studies at universities outside the Low Countries. Toebosch is open about this: ‘When you put together a curriculum you always have to make choices. When I became head of the program, it was clear that I would do things differently. Ton Broos had a literary background and was more focused in that direction, although he also set up the Anne Frank course. I am not a Dutch specialist to begin with, but a linguist.’

'If students, besides the stereotypes of tulips and cheese, already have a picture of the Netherlands, it is of a progressive country. That is not correct.'

Her choices fit in the American tradition of academic activism. Think Noam Chomsky, also a linguist. ‘If students, besides the stereotypes of tulips and cheese, already have a picture of the Netherlands, it is of a progressive country. That is not correct. As a country, the Netherlands is racist too. I want to teach students something about this, so that they may later use that knowledge to change the world elsewhere. In the Netherlands, such an approach is slightly taboo but in America people realized long ago that you can be both an academic and an activist.’

Because of this personal background, the success at the University of Michigan cannot simply be copied by departments elsewhere in the world. Fortunate for Dutch and Flemish Studies in Ann Arbor, Toebosch’s interests are closely aligned with the sea change in thinking about these issues. ‘I don’t mean to say that decolonization is a common subject here, but it has been taught for a long time. The university has a long history of promoting diversity. This has gained momentum under the current rector.’

The community of Dutch scholars

Another partnership that Toebosch prizes is with Dutch and Flemish sponsors. Initially, this was the Dutch Ministry of Education; then since its establishment in 1980 this has been the Dutch Language Union. Without this core funding or the additional grants for extra training and visiting professors, the new lecturer would not have been able to start. ‘It’s not only the money that is important here. It is more difficult to get funding from within the university if money is not also coming in from outside. Thanks to contributions from the Language Union, doors are opening here.’

Essential also is the community of Dutch scholars worldwide, of which Toebosch is a member, thanks to the Language Union. There is regular contact with the coordinator in charge. ‘That creates a bond. I have a lot of autonomy to design my program the way I want. For me that’s important. Thanks to that relationship I know about the content of other programs in America and the rest of the world. That is valuable too.’

This article was previously published in Dutch on the website of the Dutch Language Union.