American Readers Have a Love-Hate Relationship With Dutch Children’s Books

Dutch-language children’s books are doing well abroad. But when they deal with taboos, some books are too unconventional for the anglophone market. Research by Lucelle Pardoe shows that especially Dutch publishers encounter these problems, because they target large countries such as the USA and the UK. Flemish publishers do find a market for children’s books without compromising on the content or quality of the original, because they aim at other countries.

There is no art for children, there is Art. There are no graphics for children, there are graphics. There are no colours for children, there are colours. There is no literature for children, there is literature. Based on these four principles, we can say that a children’s book is a good book when it is a good book for everyone. (Francois Ruy-Vidal, publisher)

From Crossover Picturebooks: a Genre for All Ages by Sandra Beckett, page 5.

A common fallacy among adults is that books written for children are dumbed down, easier to write, and lack narrative complexity. In the Netherlands and Flanders, however, this could not be further from the case. Many children’s books fall into the “crossover” genre: defying the often-arbitrary line drawn between children’s literature and adult literature. Subject matter that might be considered taboo in other nations, like death, sex, and violence, feature in both text and illustration across Dutch-language literature for both young and old.

Dutch children’s literature is a desired export product

At the end of 2018, the Dutch Foundation for Literature (DFL) published an article boasting that Dutch children’s literature is a desired export product, citing that in 2018 alone, 202 Dutch children’s books were exported into a diverse multitude of languages and distributed around the world. Trouw followed with an explanation, expressing that Dutch children’s books are popular outside the Netherlands because they are incredibly “open”. Based on the data in the DFL translation database, however, which this article uses across the board, only 21 out of those 202 Dutch children’s books were translated into English.

In her monograph on crossover picture books, Sandra Beckett notes that when it comes to children’s books with taboo subject matter, ‘some are simply too unconventional for the Anglo-American markets’. With the DFL’s new initiatives promoting Dutch literature in English — like New Dutch Writing — publishers and grant-giving organizations would do well to consider the cross-cultural differences that keep some of the best Dutch-language books out of this enriching foreign marketplace, such that they might be circumvented through optimized collaboration between publishers. So what methods presently help Dutch children’s books cross borders into the anglophone market? The answer differs between the Netherlands and Flanders.

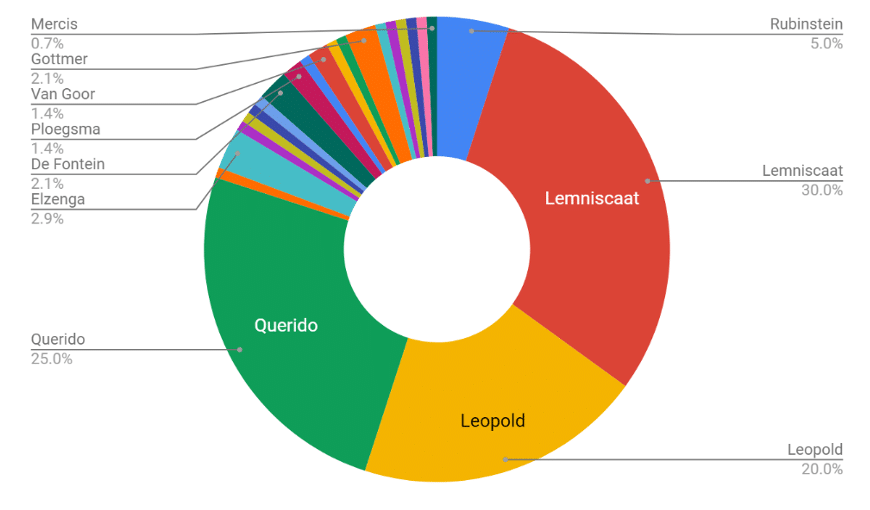

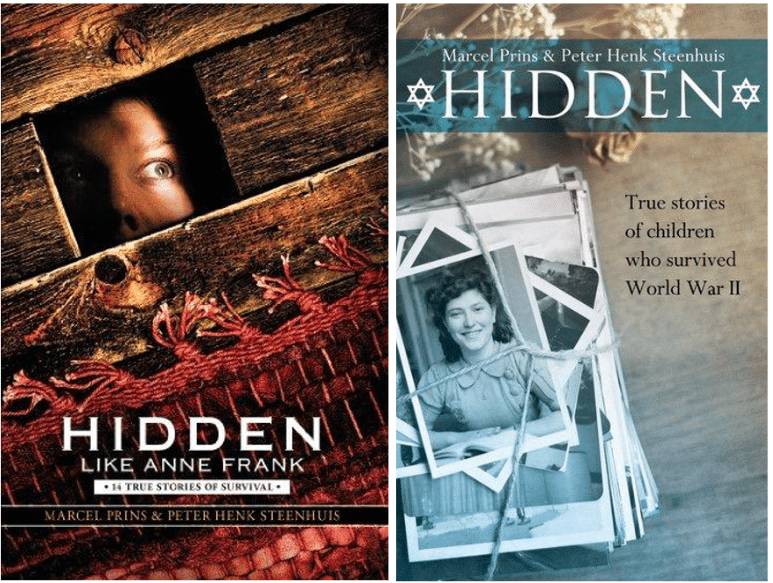

The Netherlands

In the Netherlands, Querido, Leopold, and Lemniscaat are the most prolific publishers of Dutch children’s books that appear in English. These three publishers collectively provided 75% of the Dutch source titles that were translated into English by publishers in the Netherlands in the genre of children’s literature in the past ten years. Here, in-house translation reigns: Lemniscaat publishes the vast majority of their own translations in-house through outposts in the United States and United Kingdom, while Querido and Leopold publish in-house English translations at home in the Netherlands, targeting tourists and the ever-growing expatriate and immigrant populations.

The foreign rights of these translations often go on to be purchased by English-language publishers, who then print the title for much wider distribution. By taking the initial translation of the book into their own hands, the Dutch publishers not only prove the book’s ability to sell, they also make it possible for publishers to read the product in their native languages before considering whether to acquire the foreign rights. English publishers can then evaluate whether the content of the book suits their values, and also have the reasonable guarantee that the book will be a lucrative product for their market. This pattern is shown in a few examples below:

In-house translations

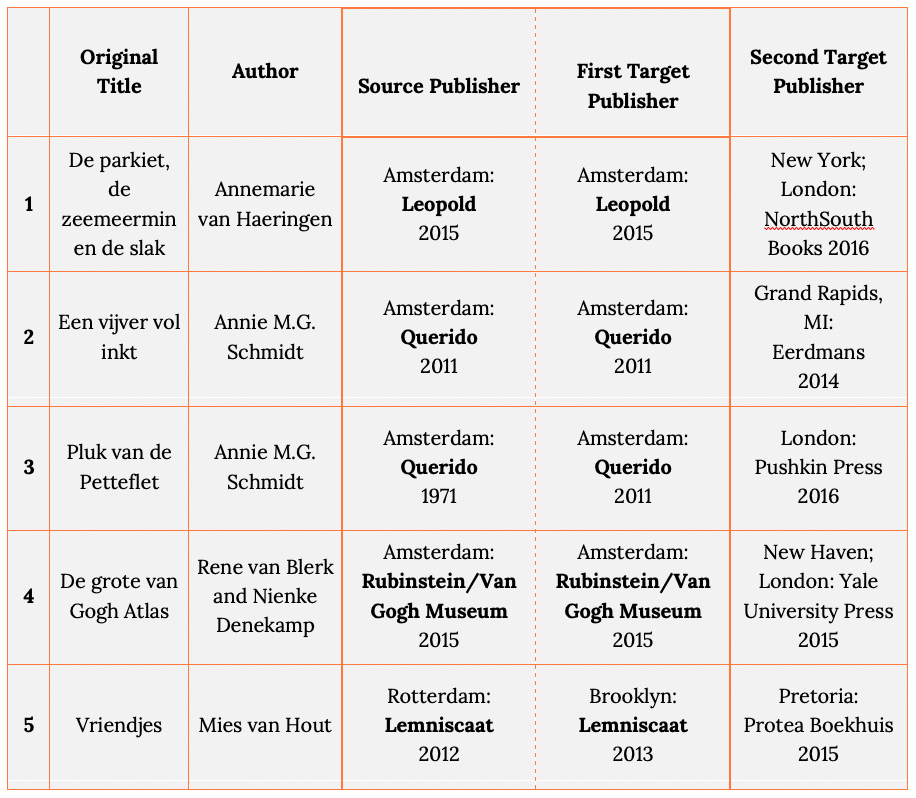

In-house translationsThere is evidence, however, that the relationship between the Dutch in-house publisher and the subsequent anglophone publisher is one in which the anglophone publisher continues to have the upper hand. For example, De parkiet, de zeemeermin en de slak (by Annemarie van Haeringen, translated by Jan Michael) underwent changes on its journey from Leopold to NorthSouth Books. While the 2015 translation was directly translated as The Parakeet, the Mermaid, and the Snail, any evidence of that initial English translation ever having existed resides only in the DFL database and in the photograph printed below (which I was only able to find on the twitter account of a Stedelijk museum attendee after an extensive amount of digging through the internet).

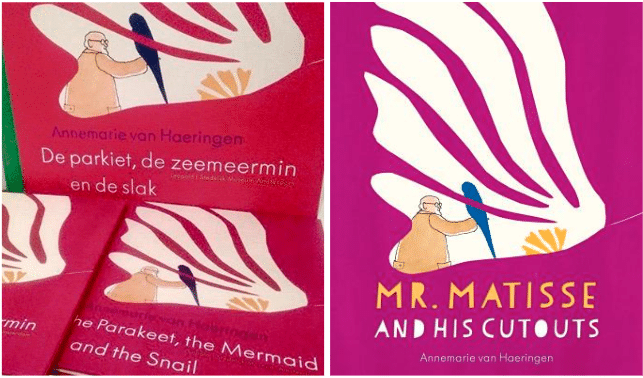

Indeed, the new product by NorthSouth Books is the only one that continues to be available in the market under the title Mr. Matisse and his Cutouts, with little remaining evidence in the international book market that Leopold ever produced the first translation. That large-scale publishers have a tendency to co-opt the ownership of the initial translation once they purchase the rights to the book is apparent time and time again. The 2014 translation of Ondergedoken als Anne Frank was published by Scholastic Books in both the USA and UK, but under different titles: Hidden like Anne Frank: 14 True Stories of Survival in the USA, Hidden: True Stories of Children Who Survived World War II in the UK. The cover art was also changed accordingly, with the anglophone publisher taking full charge of the book’s continued life in English.

The books entering the anglophone market through this in-house translation tactic, however, are fairly uncontroversial. Crossover picture books for a dual readership of children and adults continue to be an anomaly in mainstream anglophone literary markets and therefore present economic risks to Netherlands-based publishers. The Woutertje Pieterse Prijs winner Doodgewoon by Bette Westera, for example, was commissioned for an in-house translation but has yet to be printed even by Querido for fear that there is no market for a children’s book about death among English speakers. This approach to entering the anglophone market, therefore, continues to be constrained by cross-cultural differences in what can be counted as “good” or “appropriate” children’s literature. In Flanders, however, different modes of production manage to circumvent these issues, launching unique dutch-language crossovers into the International book market.

Flanders

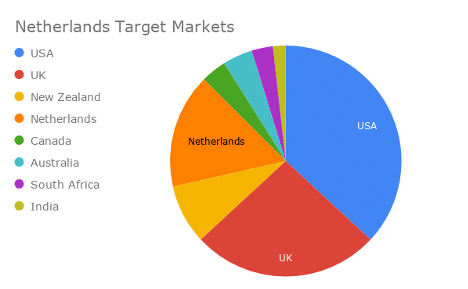

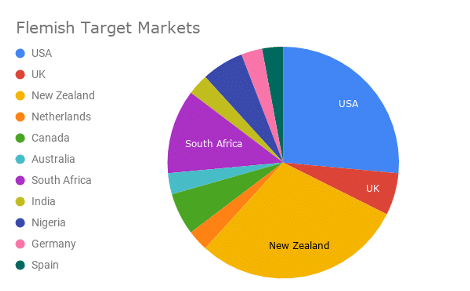

With Lemniscaat, Querido and Leopold responsible for the vast majority of Dutch-language translations travelling to the USA and the UK, these target markets are saturated by translations from large-scale Dutch publishers and are therefore all the more impermeable for the smaller-scale publishers based in Flanders. This can be seen in the charts below: While the large-scale Netherlands-based publishers send nearly 70% of their source texts abroad to the USA and UK, that percentage is significantly lower for Flemish publishers — 32,4%. Instead, Flanders initiates the export of Dutch-language children’s literature to a greater variety of smaller literary systems: Australia, Nigeria, Canada, South Africa, India, Germany, and Spain alongside the most common markets of the USA, the UK, the Netherlands, and New Zealand. Foregoing the practice of in-house translation altogether, Flemish publishers look further afield to build social capital among a selection of publishers that share their values in a more diverse selection of anglophone markets abroad.

Let us look at De Eenhoorn as an example — the most prolific Flemish publisher when it comes to selling the foreign rights for their children’s books to anglophone publishers. Their mission statement on their website outlines their three main criteria (my translation):

. Original Stories that appeal to adults as much as they do to children. Original subject matter and beautiful language use are priorities here too.

. Unique Illustrations with the room to experiment. The illustrator should have the chance to realize his or her own fantasy and to fully develop within their own style.

. And an attractive design and form with an eye for detail.

De Eenhoorn’s aesthetic, age-defying books cross borders into anglophone markets consistently because their foreign rights choices have less to do with the potential for exposure in the US and UK than they do with placing work in the hands of agents who will do the original justice without co-opting the book’s symbolic value. The publishers who they work with share their values and modes of production: UK based Book Island is ‘an indie publishing house for picture books in translation, specializing in beautifully illustrated, high-quality picture books that can be enjoyed and treasured by both parents and children’.

Another popular publisher with De Eenhoorn is Groundwood Books in Canada, who state that they ‘look for books that are unusual; we are not afraid of books that are difficult or potentially controversial; and we are particularly committed to publishing books for and about children whose experiences of the world are under-represented elsewhere’. Eerdmans Press, De Eenhoorn’s most prolific partner based in the United States, also expresses a desire to publish challenging books: ‘These children’s books tell delightful stories about adventure, family, and friendship, but they also help children wrestle with special issues, such as grief, divorce, racism, poverty, and war’.

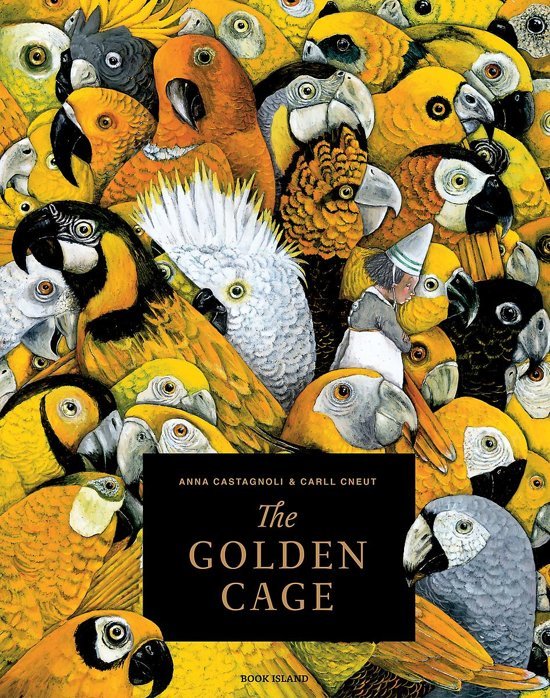

Leveraging these relationships, De Eenhoorn has successfully collaborated on the translations of dark crossover picture books illustrated by Carll Cneut — some of their most popular publications within Flanders — without compromising on the content or quality of the original. In 2019, Book Island planned a translation of ‘The Golden Cage, a deliciously dark European picture book’. Written by Anna Castagnoli and translated by Laura Watkinson, this book is illustrated in classic Cneut style and has a dark plot to match:

‘Valentina the emperor’s daughter is an obsessive collector of exotic birds. Her servants track down every bird she desires – just one remains unfound: a bird that talks. Servants search far and wide to fulfil her impossible quest – and she beheads those who fail. In Valentina’s palace, heads roll every day! Will the golden cage ever be filled?’

Book Island, however, did not have the means — the economic capital, that is — to produce the translation of the Golden Cage, having been unable to secure additional funding for the project from UK-based organizations due to the violently rolling heads. They started a Kickstarter campaign asking potential consumers of the book to help fund its translation: ‘Why we need your support? This type of book is very popular in Europe, but difficult to find in the UK as the market has a large emphasis on mass production and less on high-quality, thought-provoking picture books’.

Citing the non-existence of the form of the crossover picture book in the anglophone market, Book Island had no choice but to find economic capital by leveraging social capital: their network. Remarkably, their campaign was an unprecedented success. Book Island raised nearly four times their target: ₤7,301. They produced the translation to great success in the United Kingdom and will hopefully be able to continue to do so with future iterations of “challenging” books from the Dutch literary market.

Censorship

The collaboration between De Eenhoorn and Book Island, with their aligning missions, shows that social capital can effectively drive the translation of subversive books that are too unconventional to receive the funding and support from large-scale publishers or grant-giving institutions. Though this may require more work than if the book were to be accepted by a large-scale publisher, the process of mass production is more likely to include the interference of the large-scale publisher in the final product, potentially leading to censorship.

Close collaboration when it comes to crossover literature is therefore both preferable and more effective, although in need of financial stimulation from grant giving institutions. The Dutch Foundation for Literature and Flemish Literature Fund might turn their attention to this pattern through their current initiatives for the promotion of Dutch literature abroad, to the grizzly delight of Dutch and English-speaking children around the world.

The graphs are my own, generated based on data pulled from the Dutch Foundation for Literature Database of all children’s literature translated from Dutch into English from 2009 – 2019.