Countering the Forgetting: Dutch Indies Literature in the Twenty-First Century

What role does Dutch Indies literature, in the widest sense, play here and now, a lifetime after the end of the colonial era, in a Netherlands that has changed almost beyond recognition? Since Max Havelaar, Dutch Indies writing constitutes some of the best that the Netherlands has to offer in the literary field. It still plays off colonial myths and realities against each other, and finds words for painful, half-forgotten things.

In his large-scale history of Indies literature, Oost-Indische Spiegel (1972; Mirror of the Indies, 1982), the writer and literary scholar Rob Nieuwenhuys (1908, Semarang – 1999, Amsterdam) gives an overview of “what Dutch writers and poets have written about Indonesia from the first years of the Dutch East India Company down to the present”. Literature is defined broadly: alongside novels and poems, it includes history writing, stories, journalism, letters, diaries and other documents, seen in their socio-cultural and colonial-historical context. In taking this broad view Nieuwenhuys was following the example of the writer E. du Perron (1899-1940), who was concerned in texts with such questions as: how well do those authors write? what have they got to say? what is special about their point of view? what kind of style and personality emerges from their work?

Whoever knows nothing of the Indies, cannot understand the Netherlands properly

Following their example, I want to discuss here the Indies writing of the past twenty years. That is over three quarters of a century since the end of the Dutch East Indies, an end that may seem a long time ago, but that is far from forgotten. The world may have changed radically in the meantime, the colonial era is over and since then the Netherlands has changed almost beyond recognition. But it is still true that someone who knows nothing about the Indies does not properly understand the Netherlands.

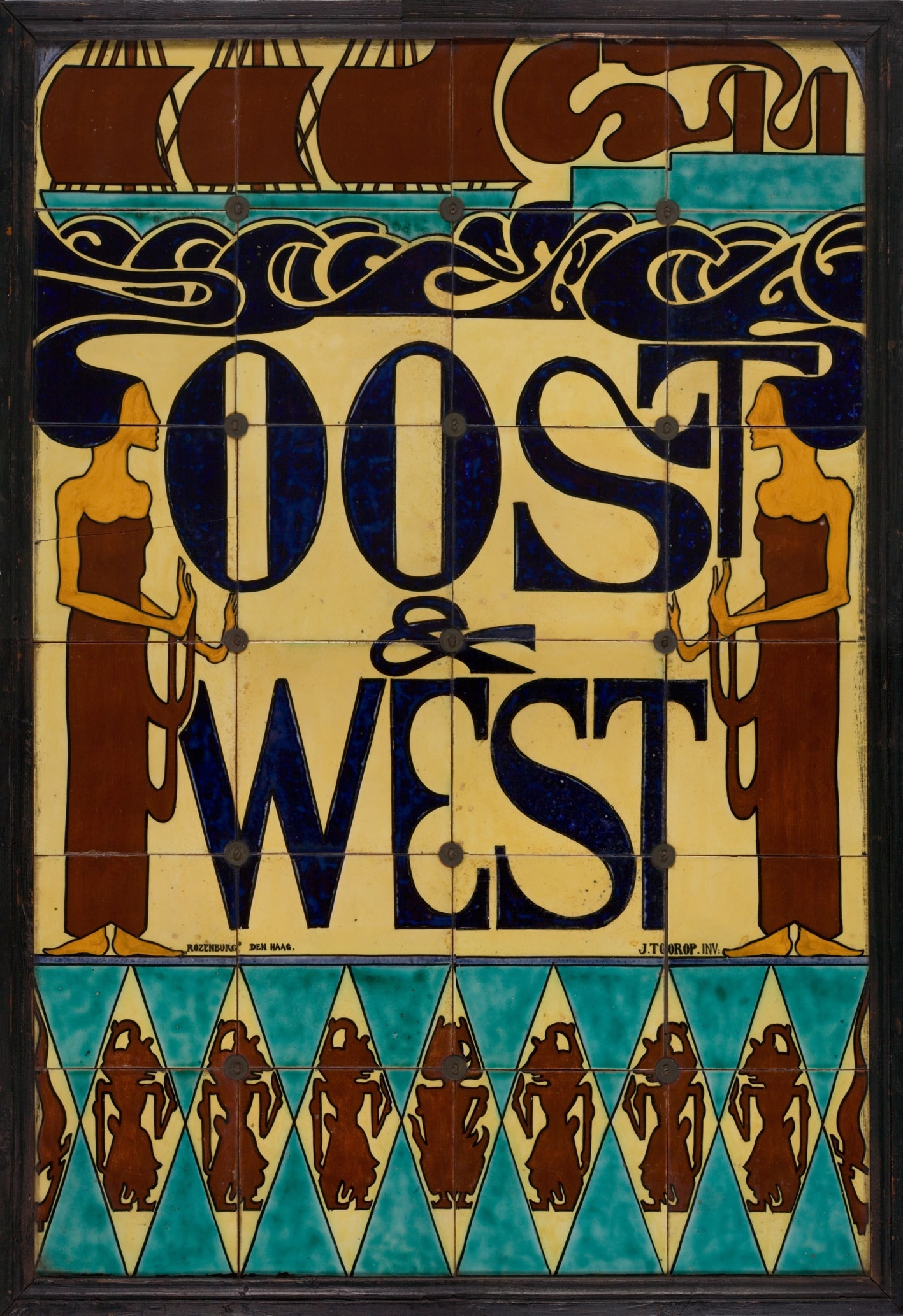

Jan Toorop, East and West, 1900

Jan Toorop, East and West, 1900© KITLV, Leiden / Europalia Indonesia

Traces of the Indies and the colonial past are still markedly present everywhere in the Netherlands – a heritage that in our present is set in a different context than in the past. What was once far away, beyond the horizon in the East, is now all present in the Netherlands, right next to us, among us, around us and confronting us, and this has triggered processes – of recognition, adjustment, image-forming, criticism and (re)appraisal – as a result of which the meaning that the Indies had and continue to have for the Netherlands has radically altered in the last few decades. In brief: from tempo dulu (the good old days) and colonial nostalgia to the multicultural society of the present-day Netherlands.

It is in this dynamic (and contested) context that Indies literature plays its role and finds its place. And my question here is: what is the state of Indies literature at this moment in time, a lifetime after the demise of the Dutch East Indies?

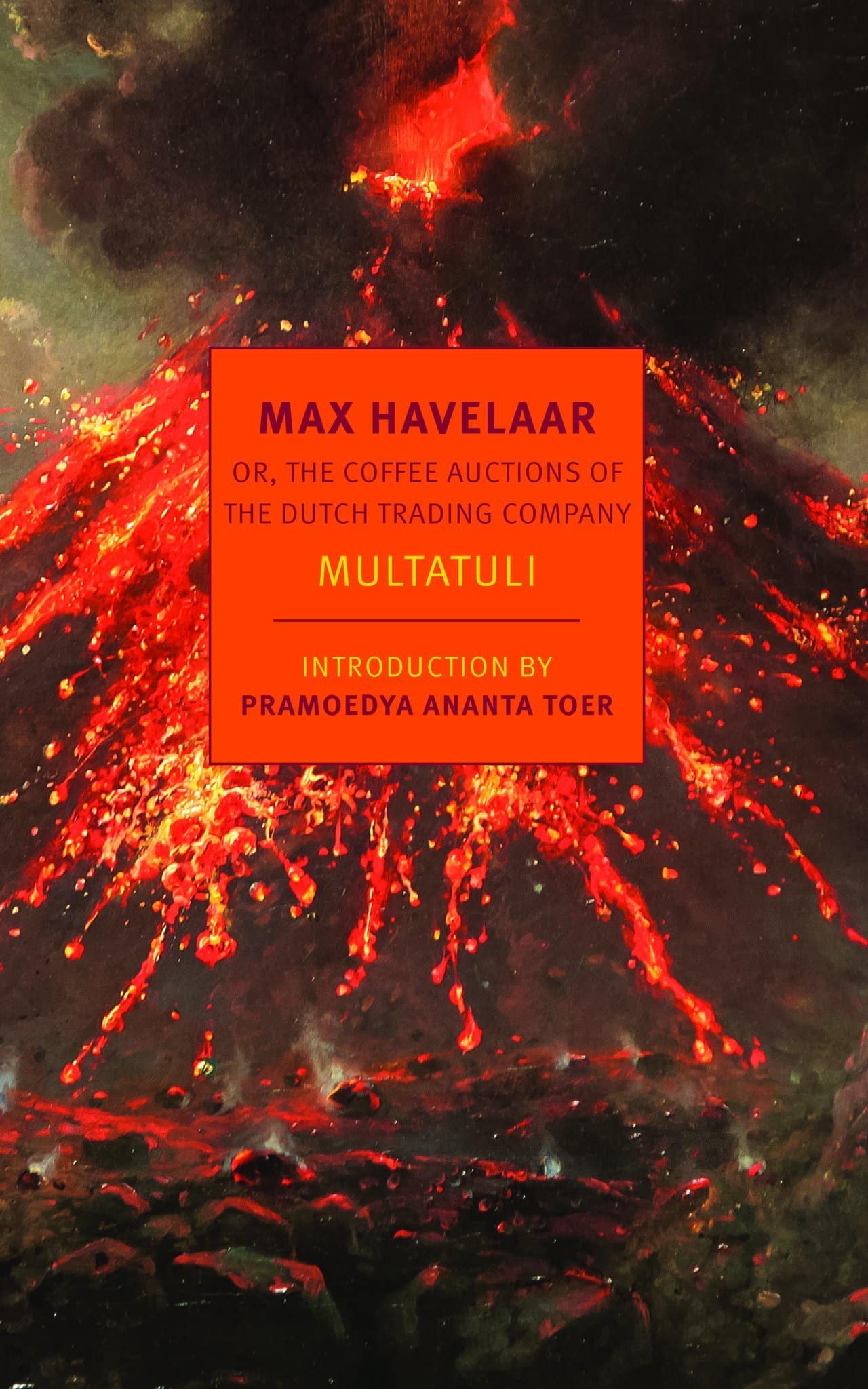

Max Havelaar: the Big Bang

Multatuli, author of 'Max Havelaar' (1820-1887)

Multatuli, author of 'Max Havelaar' (1820-1887)In the period from 2000 to the present, which is central here, Multatuli’s work proves to be just as alive and well as it was in 1860. As early as 2001 Tom Phijffer, in his essay Het gelijk van Multatuli (Multatuli was Right), posts a sharp refutation of the ex-colonial view held by Rob Nieuwenhuys of Havelaar/ Douwes Dekker, Multatuli’s alter ego, as an official who flouted all the rules. On the contrary, as Phijffer shows, assistant-resident Douwes Dekker devoted himself wholeheartedly during his time in Lebak to the task entrusted to him in his oath of office, namely to protect the native population.

In 2005 there follows the completion of Multatuli’s 25-volume Collected Works, with an official presentation to the then crown prince Willem-Alexander, and accompanied by lively exchanges on paper between W.F. Hermans, Kees Fens, Hugo Brandt Corstius, K.L. Poll and Tom van Deel.

In 2006 the status of Max Havelaar as the greatest Dutch novel is underlined by the inclusion in the Canon of the Netherlands of a separate Multatuli window on ‘Injustice in the Dutch East Indies’. In 2010, on the hundred-and-fiftieth birthday of Max Havelaar, NRC journalist Gijs van Es publishes an abridged and modernised version to win over young readers to this book, advocating honest dealing and fair trade against corruption and extortion. In the journal Nieuw Letterkundig Magazijn (vol. 28) this leads to fierce discussion, though without mention of a previous abridgement published in 1948 and aiming, in the middle of the Indonesian War of Independence, to spread Multatuli’s passionate indictment of injustice and colonial domination as widely as possible among the population. It did so with a new Preface stating that “today we may no longer write stories of Saidjah and Adinda; instead, we’d write about the burnt-out houses in Bekasi or the death train of Bondowoso” (well-known atrocities at the time). It also included the provocative Curse by Sentot on ‘The Dutchmen’s Last Day in Java’.

Multatuli is still a towering figure

In 2010 too, the Max Havelaar prompted a series of lectures at the University of Amsterdam with incisive discussions on colonial history, political writing, whistle-blowers and fair trade. In 2012 follows Atte Jongstra’s Kristalman (Crystal man), one of the most cheerful and entertaining books ever about Multatuli. He clearly still is a towering figure – which is entirely due to the special qualities of his Max Havelaar. To begin with, the novel offers a great variety of voices, personalities, narrators, styles and language registers. For example, no one in the whole of Dutch literature had ever before written in ordinary, everyday and extremely accessible Dutch. The multiplicity of I’s in this novel, ranging from the idealistic colonial civil servant Max Havelaar to the penny-pinching colonial coffee trader Batavus Droogstoppel, each with their own voice, are all played off against each other by Multatuli. And through their mutual contradictions and Multatuli’s sarcastic commentary, the question of truth becomes central.

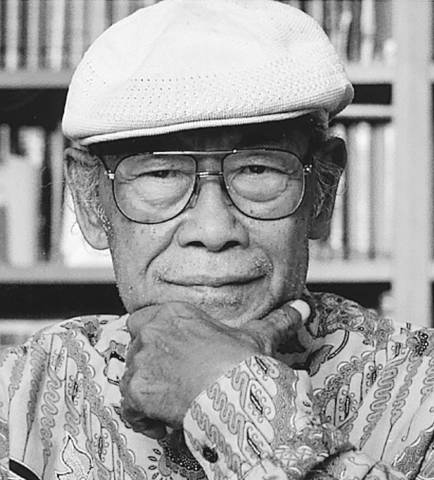

Pramudya Ananta Tur (1925-2006)

Pramudya Ananta Tur (1925-2006)© Wikipedia

But as a result of all those contradictions, the novel has no unambiguous interpretation, and so Max Havelaar was able to function in the colonial period not only as the Bible of young and idealistic Dutch officials of the Dutch East Indies administration, but equally – for the Indonesian writer Pramudya Ananta Tur, for example – as “the book that killed colonialism”. What Pramudya and other Indonesians saw acutely was the revolutionary way in which Multatuli, in his best-known tale, ‘The Story of Saidjah and Adinda’, places a Javanese peasant boy centre-stage, with a name, Saidjah, a voice, a story; a human being like you and I, with ideas, longings, dreams and songs, hardworking and in love; opposed to which is the oppression and exploitation by the colonial administration and its army – which finally destroys him, in the coffee-plantations and the robber state that the magnificent emerald girdle of the Indonesian archipelago proved to be.

With the literary game which Multatuli plays here and which defies all set conventions – from the very first sentence which against the rules begins with I, to the end with his fierce indictment addressed to the Dutch King – he succeeds in having his readers question their conscience. Anyone who has read Max Havelaar can no longer read a Dutch colonial text innocently.

Anyone who has read Max Havelaar can no longer read any Indies text innocently

Through the Indies, Multatuli caught fire as a writer, as did many more writers after him, for whom the Indies were an inexhaustible source of inspiration: writers like P.A. Daum, Louis Couperus, Arthur van Schendel, E. du Perron, A. Alberts, H.J. Friedericy and Maria Dermoût, who between 1890 and 1960 produced the Indies Canon. These classic works, which exert an enduring fascination, are all available in English in E.M. Beekman’s twelve-volume Library of the Indies and discussed in his monograph Troubled Pleasures (1996).

The best of the Indies is at the same time the best of the Netherlands

So, were the Indies a source of raw material for the Netherlands in a literary sense too? Yes, but much more besides. Since Max Havelaar, Indies writing has been among the best that the Netherlands has to offer in the literary field. Put more forcefully: the best of the Indies is at the same time the best of the Netherlands.

The Twenty-First Century: Memory, Imagination and Research

When the actual Indies were lost after the Second World War, and could only continue to exist as a realm of memory and imagination, this branch of literature flourished extensively. It still does: from 2000 to the present we find in almost every year a unique book in one of the genres of Indies literature in the broadest sense.

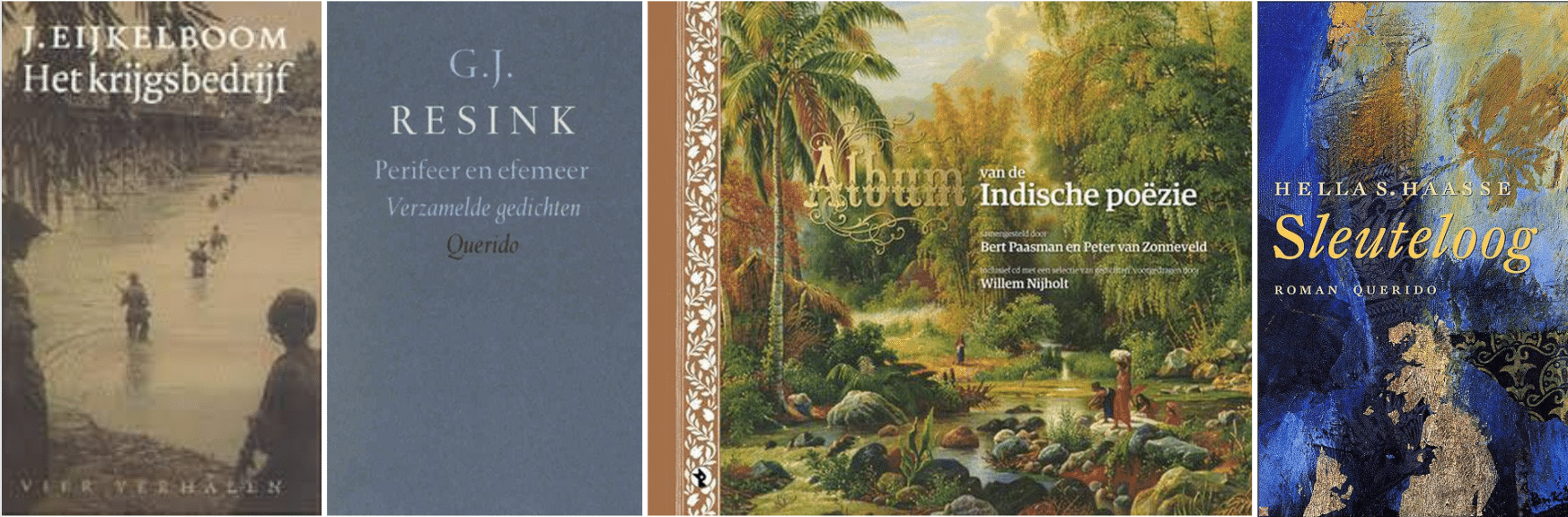

The year 2000 opens the series with the story collection Het krijgsbedrijf (Waging War) by Jan Eijkelboom, five exceptional stories from his time as a soldier in Java during the police actions. Next, in 2001, came G.J. Resink, one of our best Indies poets, with his poems collected in Perifeer en efemeer (Peripheral and Ephemeral), followed in 2014 by the great Album van de Indische poëzie (Album of Indies Poetry) compiled by Bert Paasman and Peter van Zonneveld. In 2002, over fifty years after her famous novella Oeroeg (1948; The Black Lake, 2012), Hella Haasse publishes her last Indies novel, Sleuteloog (Eye of the Key) in which she looks back at her youth and her friends in Batavia, including a scathing literary portrait of Rob Nieuwenhuys.

Marion Bloem

Marion Bloem© Wikipedia

These publications mark the end of an era. At the same time the new Indies novels of the post-war Second Generation appeared, featuring intense intergenerational conflicts and a literary coming to terms with memories, feelings, family ties and tensions, and the vicissitudes of their Indies past. Marion Bloem, who made her debut in 1983, continues with Meisje van honderd (Girl of a Hundred, 2012) and in 2020 her Indo, een persoonlijke geschiedenis over identiteit (Mixed race, a personal history about identity). Then there is Adriaan van Dis, with his Familieziek

of 2008 (Repatriated, A novel in sixty scenes, 2008) and in 2014 his Ik kom terug (I’ll be back). From 1995 Van Dis also promoted the Winternachten-festivals (Writers Unlimited) in The Hague, with their celebration of the literatures of what were once Dutch colonies, through post-colonial interaction with young writers from the former East Indies, South Africa and the Caribbean.

Adriaan van Dis

Adriaan van Dis© Wikipedia

The same global vision was found earlier in the work of the Indo (= Eurasian, mixed-race) writer Tjalie Robinson. The sparkling dialogues in his stories recreate the street life in the Batavian Indo community at the time, and just as with his equally realistic Indian fellow-writer R.K. Narayan, it is the details that establish irretrievable time and hence unleash the imagination. After the end of the Indies Robinson, with his magazine Tong Tong, became the champion of the Indo community and managed to secure its own respected place in the post-war Netherlands. Partly through his innovative ideas on mixed culture, multicultural interaction and fusion his annual Tong Tong Fair (since 1959) has in the meantime grown into the largest multicultural festival in Europe. The important thing here is the message Robinson projected far beyond the bounds of Indies literature: his inclusive realism, with its polyphony of people of mixed race, colour, religion, culture and identity; people for whom diversity is an everyday living reality in their families, circle of friends and social contacts; people who know what it is like to deal with differences. In this way the process of integration of the Indies community into its country of destination has made an important contribution to the transformation of the Netherlands into the multicultural society it is today.

Tong Tong Fair

Tong Tong Fair© Holland.com

As we learn from the new handbook of Indies literature, De Postkoloniale Spiegel

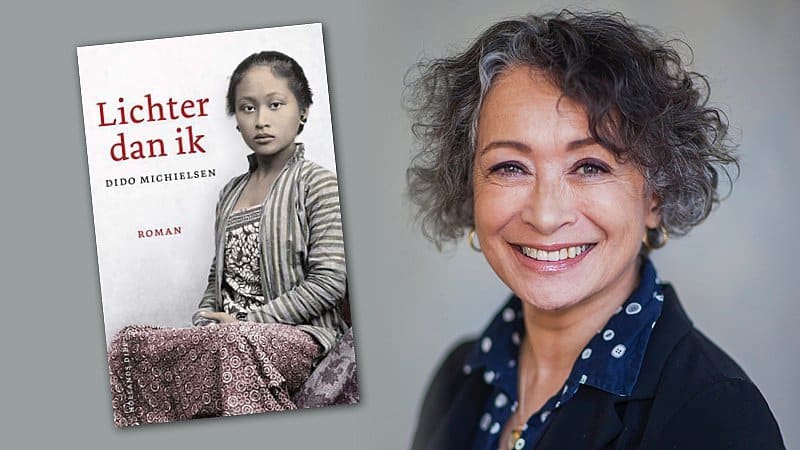

(The Postcolonial Mirror, 2021), further exploration of Indo identities today takes us to the historical novel by Dido Michielsen, Lichter dan ik (2019; Lighter than me), in which she recreates the 19th-century life of her unknown native Javanese great-great-grandmother, whom she names nyai Isah – in counterpoint to Njai Isah (1904), the Malay-language novel written by Isah’s son, Ferdinand Wiggers (in real life Michielsen’s great-grandfather). Lichter dan ik is the tale of Isah’s resistance to her own vanishing from history: beginning as the concubine (nyai) of a Dutchman, she bears him children; he in turn marries a Dutch woman and dumps Isah; at risk of losing out, she does anything she can to hang on and stay close to her children, almost her only trace left in the world; even serving as their ayah when through adoption they have turned into Europeans and are forgetting even the name of the woman who is and will always remain their mother.

Dido Michielsen

Dido Michielsenphoto © Harold Pereira

Difficult and Painful Questions

At the same time Indies literature today offers a forum for broaching difficult and painful questions, the revelation of truths that matter and that reach far beyond the bounds of literature.

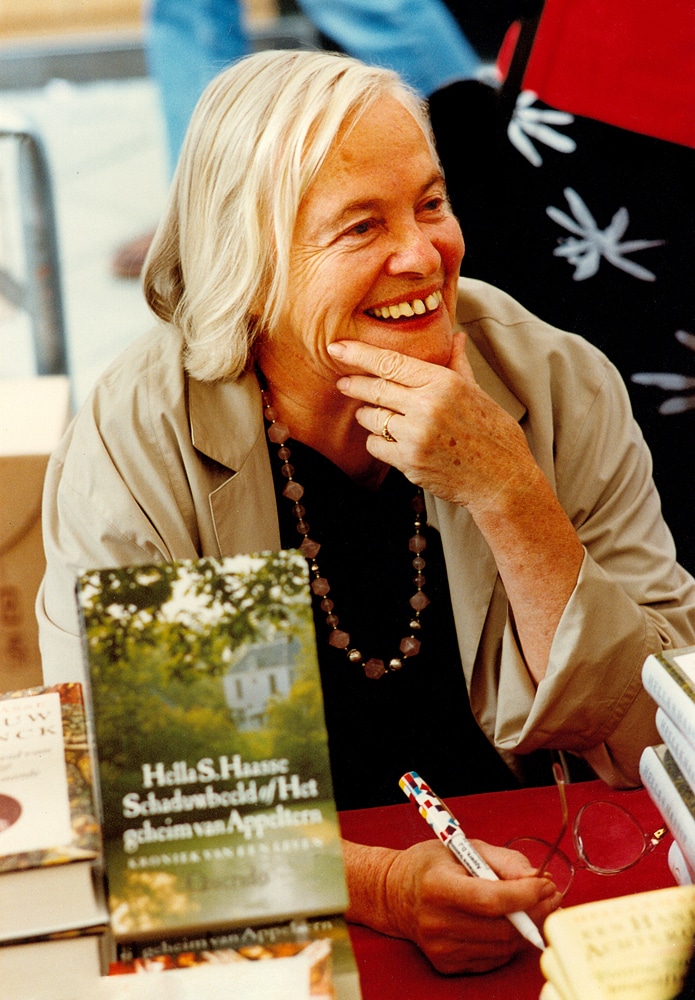

Hella Haasse (1918-2011)

Hella Haasse (1918-2011)© Wikipedia / Aaron Sikkink

The most obvious of these is the way in which the end of the Indies was dealt with. It began already in Oeroeg, when in Hella Haasse’s tense final scene the old Indonesian friend the Dutch narrator had been looking for tells him: “Go away, otherwise I’ll shoot. You have no business being here”, and the latter hence has to say farewell to the land of his birth – as in the real world, from 1946 on, more than 300,000 refugees plus over 130,000 Dutch soldiers were forced to ‘go home’ to Holland. For many of them, often with family both in the Netherlands and in Indonesia, this meant a most painful separation, and in subsequent decades this has led to a lively debate, with a multitude of personal and cultural ramifications, on the question of who or what is truly “Indies” in the Netherlands. Marion Bloem did not want to be an ordinary Indies girl. Hella Haasse on the other hand did want to be one, but was not allowed to, especially by Rob Nieuwenhuys. But things can change, and between Oeroeg and Sleuteloog she has grown into the grande dame, the Yourcenar of Indies writing.

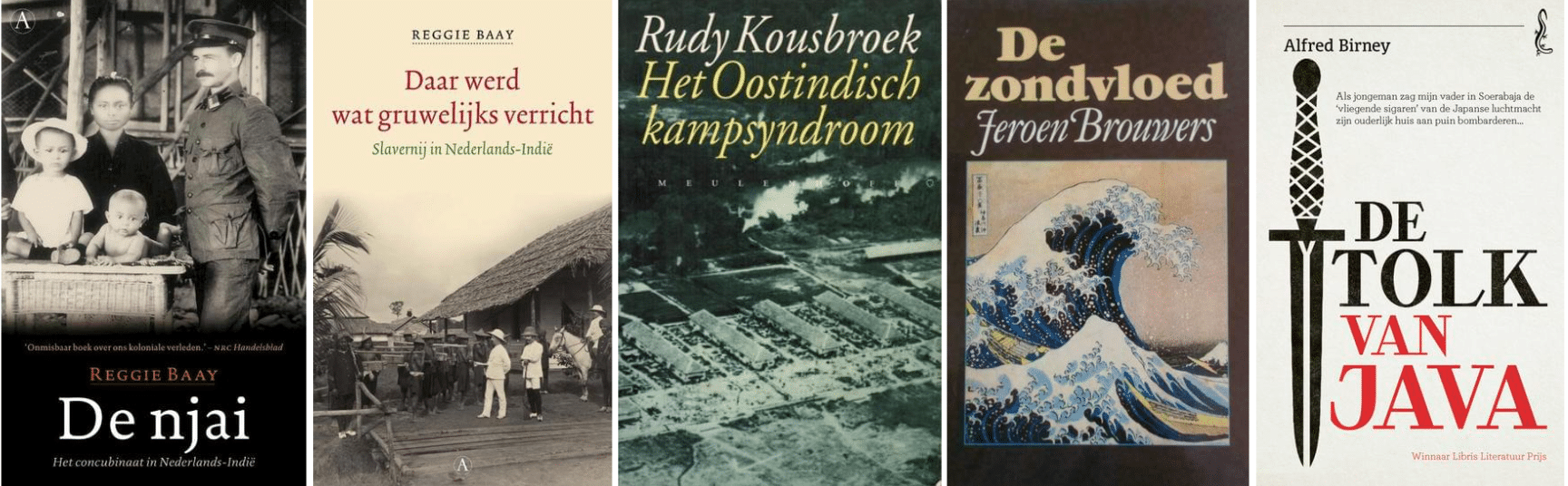

No less revealing is how Reggie Baay has been able in recent years to add two virtually unknown chapters to Indies history. First in 2008 with De njai (The Concubine), his history of the native female ancestor often air-brushed out of colonial family histories, as in Dido Michielsen’s novel about nyai Isah. And then in 2015 in Baay’s path-breaking Daar werd wat gruwelijks verricht (Something Gruesome Happened There), in which Baay writes the very painful history of slavery in the Dutch East Indies – “I’ve never heard of such a thing”, as Droogstoppel would say.

Again and again there is also the theme of war and violence that recurs in Indies literature. In 2013 the seventh edition appears of Rudy Kousbroek’s extraordinary collection of essays and documents, Het Oostindisch kampsyndroom (The East Indies Camp Syndrome, 1985), followed in 2010 by Jeroen Brouwers’ collected Indies novels: Het verzonkene (What is Submerged, 1979), Bezonken rood (1981; Sunken Red, 1998) and De Zondvloed (The Deluge, 1988). In fact this is a reprise of the 1980s when the clash between Kousbroek and Brouwers led to a fierce literary debate about truth and lies over the Japanese occupation of the Indies from 1942 to 1945.

Again and again the theme of war and violence recurs in Indies literature

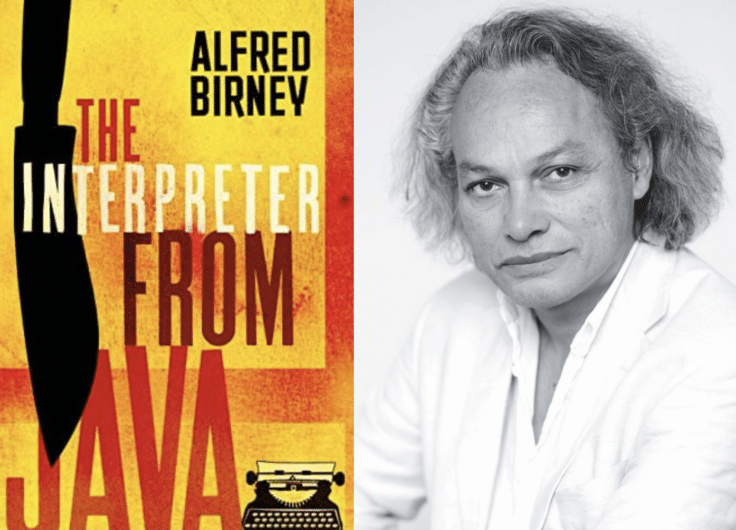

Following on, in 2016 Alfred Birney made a major impact with his De tolk van Java (The Interpreter of Java, 2020), for which he received both the Libris Literature Prize and the Henriëtte Roland Holst Prize. It is the harrowing story of his mixed-race father’s traumas from serving as an interpreter/interrogator with the Dutch marines on Java, torturing and killing his Indonesian enemies – first in real life in the forties, afterwards in his gruesome nightmares back in Holland – as told by his son, Alfred Nolan, struggling to survive and escape from the sadistic abuse and cruelty he suffers at his father’s hands.

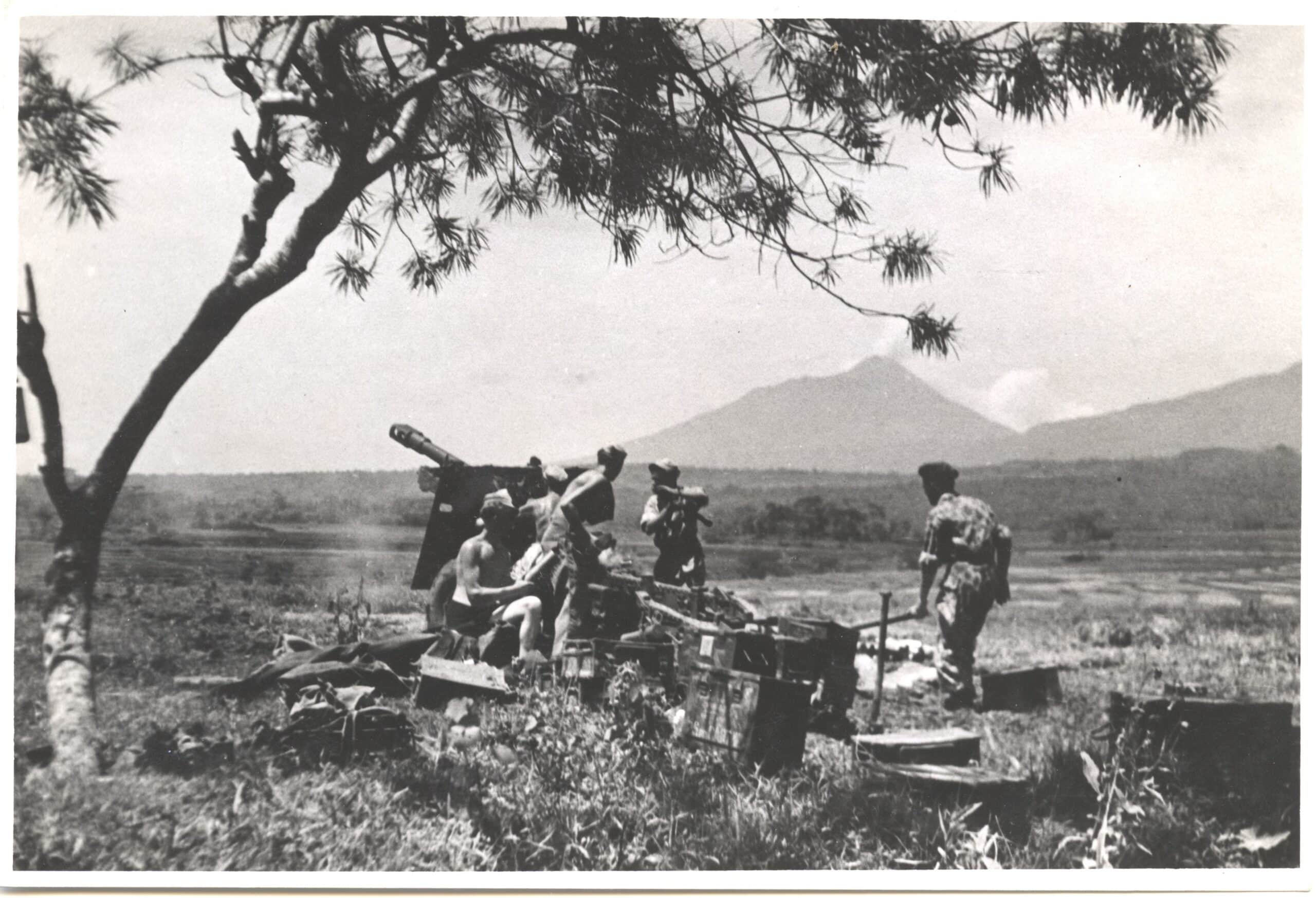

Dutch artillerymen in action near Reksosari, Central Java, 1947

Dutch artillerymen in action near Reksosari, Central Java, 1947Source: NIMH

That same year also saw the shattering studies on the war of colonial reconquest which the Netherlands waged between 1945 and 1950 against the young Indonesian Republic: De brandende kampongs van general Spoor (General Spoor’s Burning Villages) by Rémy Limpach, and Soldaat in Indonesië 1945-1950. Getuigenissen van een oorlog aan de verkeerde kant van de geschiedenis (A Soldier in Indonesia 1945-1950. Testimony on a War on the Wrong Side of History) by Gert Oostindie. What one reads in these historical studies was and is shocking, in particular for those who still believe in the myth of the Dutch East Indies as a model colony.

For many Dutch people it is still very hard to accept that in Indonesia the Netherlands was the exploiter, oppressor and perpetrator instead of the victim

For many Dutch people, it is still very hard to accept that in Indonesia the Netherlands was the exploiter, oppressor and perpetrator instead of the victim. But reading Limpach and Oostindie makes one understand why the lawyer Liesbeth Zegveld, who is also Professor of International Humanitarian Law in the University of Amsterdam, still persists today in prosecuting the Dutch State for war crimes committed in the 1940s, such as the terrible massacre in the village of Rawagedeh in West Java on 9 December 1947.

The graves of Indonesian victims of the 1947 massacre by Dutch military troops at the Rawagede memorial.

The graves of Indonesian victims of the 1947 massacre by Dutch military troops at the Rawagede memorial.That the Dutch-Indonesian conflict of 1945-1950 was actually a dirty colonial war, was demonstrated in 2002 by Stef Scagliola in her Last van de oorlog. De Nederlandse oorlogsmisdaden in Indonesië en hun verwerking (The Burden of War. Dutch War Crimes in Indonesia and How They Were Dealt with) – and before her, back in 1970, in the classic study by Van Doorn and Hendrix, Ontsporing van geweld

(Violence off the Rails, 19853) on the extreme violence used by the Dutch against the new Indonesian Republic.

Seventy years after the end of that conflict, in early February 2022, two events in Amsterdam have directly confronted the Dutch nation with its colonial past. First, in the Rijksmuseum, there is the historical exhibition Revolusi! Indonesia Independent, organised jointly by Dutch and Indonesian curators, who – like David van Reybrouck’s Revolusi (2020) – take a new, critical and often moving look at the epoch-making anti-colonial struggle of the Indonesian Republic against the Dutch. Secondly, at the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences, a few days later, the results were published of the historical research programme ‘Independence, Decolonization, Violence and War in Indonesia 1945-1950’, carried out jointly by Indonesian and Dutch historians. In the course of this year, they will publish a series of specialist monographs with Amsterdam University Press.

Of particular importance here is the unequivocal conclusion of these historians that the Dutch State during the Indonesian war of 1945-1949 did in fact commit wide-spread, structural and extreme violence; and that this was often condoned, hardly sanctioned and usually covered up by those responsible at the highest level of the Dutch state, in the military, the judiciary, the civil service, in politics and parliament, and the government.

Accepting these findings – and following on from King Willem-Alexander’s apology to the Indonesian people in Jakarta in 2020 – prime minister Rutte has now, for the first time, taken full responsibility for this collective failure on behalf of the Dutch government and its predecessors, on 17 February 2022, when he offered his “sincerest apologies” to the Indonesian people, as well as to anyone in the Netherlands who has been affected by this and has had to live with the consequences.

Reassessment and Reconciliation

Does this make good the atrocities mentioned above, in the 1948 edition of Multatuli’s Max Havelaar or in many other contemporary sources? No. But it does mark a sea change in Dutch public debate on decolonization. And it does remind us of the key role that Indies literature has had over and over again, with its critical playing off against each other of colonial myths and realities. Multatuli was concerned with the truth, and for the same reason Kousbroek and Brouwers write to counter the forgetting and misunderstanding of what happened way out East in the past. So did Pramudya Ananta Tur. So do Indies writers of today, such as Alfred Birney.

Indies literature says what for a long time could not be said and which now cries out for reassessment and reconciliation

Here and now, in a very different time – post-colonial, multicultural, and with human rights as a central value – Indies literature still plays this Multatulian role: speaking truth to power, finding words for painful, half-forgotten things; saying what for a long time could not be said and what now, finally, cries out for reassessment and reconciliation; and doing so through exceptional works of memory, imagination and critical research.