The Call of the Orient: Dutch Migration to East Asia

Through the ages, people have migrated from the Low Countries to all the corners of the globe. One area that has seen ongoing migration from this area since the turn of the seventeenth century is East Asia. The reasons for this are complex, but essentially they have to do with the struggle for the independence of the United Provinces from Spain and its ally Portugal, and of course trade, primarily in the form of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Many Dutch contributed to Asian culture and society in various ways.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC), founded in 1602, was probably once the largest joint-stock company in the world. Its operations stretched from North-East Asia to Southern Africa and involved the establishment of many trading posts such as those in Ceylon, Bengal, the East Indies, Taiwan and Japan. When it was declared bankrupt in 1799, its assets and activities were taken over by the Dutch state, and as is well known, the Dutch East Indies remained a Dutch colony until the middle of the twentieth century. The VOC was a multinational organization, employing not only Dutchmen (employees were typically men) but also other Europeans and, in particular on the intra-Asian trade, people from South and East Asia. While some of the Dutch could be seen as merchants or employees who went to East Asia for a limited period to work, others spent a considerable part of their lives in East Asia, some even dying there, and could therefore be seen rather as more permanent migrants.

A senior merchant of the Dutch East India Company, presumably Jacob Mathieusen, and his wife; in the background the fleet in the roads of Batavia, Aelbert Cuyp, c. 1640-1660

A senior merchant of the Dutch East India Company, presumably Jacob Mathieusen, and his wife; in the background the fleet in the roads of Batavia, Aelbert Cuyp, c. 1640-1660© Rijksmuseum

Confidant of the Shogun

The first Dutch to reach Japan, in 1600, arrived aboard the Liefde (Love). They were not allowed to leave the country and so some of them turned a negative to a positive and established themselves as merchants or pilots of Japanese ships. Jan Joosten van Lodensteyn married a Japanese Christian woman and would eventually move to Edo (now Tokyo), where as well as trading he became a confidant of the Shogun, the military ruler of Japan, on foreign and military affairs and contributed to the development of relations between the United Provinces and Japan. His name survives in a Japanese form of Jan Joosten, Yaesu, in the names of several places in central Tokyo such as Yaesu kitaguchi (the northern entrance to Tokyo Central Station).

First Western women in Japan

Hendrik Doeff by Charles Howard Hodges, between 1817 and 1822

Hendrik Doeff by Charles Howard Hodges, between 1817 and 1822Dutchmen often took Japanese wives or concubines. The head of the Dutch trading post in Japan (opperhoofd) for almost ten years, Cornelis van Nijenroode, had a daughter with his Japanese concubine, Cornelia, who became a wealthy merchant in Batavia (now Jakarta). A later opperhoofd, Hendrick Doeff, had to stay in Japan for fourteen years (1803-1817), largely as a consequence of the Napoleonic Wars. However, he put his time to good use, producing an important Dutch-Japanese dictionary, which allowed Japanese to translate many Dutch scientific books into Japanese. His successor, Jan Cock Blomhoff, brought his family to Deshima, including his wife, Titia, their son, Johannes, and a Dutch wet-nurse, Petronella Muns. Unfortunately they were not allowed to stay, but the women caused quite a stir as the first Western women in Japan for over 150 years. Artists made many pictures of them.

Deshima in the shadow of modern Nagasaki buildings

Deshima in the shadow of modern Nagasaki buildings© Christopher Joby

After Japan was forced by the USA to open its ports to other countries in 1854, many Dutch went to Japan to help to modernize the country. Jonkheer J.L.C. Pompe van Meerdervoort, a naval medical officer, spent five years in the country, overseeing the construction of the first military hospital in Japan. The Dutch chemist A.J.C. Geerts arrived in Japan in 1869 and would become the head of a new government scientific laboratory in Kyoto. He remained in Japan for the rest of his life and was awarded with the Order of the Rising Sun two weeks before his untimely death in 1883.

The Dutch who went to Japan contributed to Japanese culture and society in various ways. Japanese translated over 1,000 Dutch books, which would influence fields such as medicine, botany and astronomy. Japanese artists, such as Hokusai, adopted Western-style perspective in their paintings, and there are several hundred Dutch loanwords in modern Japanese, of which bīrū (beer from the Dutch bier) and kōhī (from the Dutch koffie) are perhaps the two most obvious examples.

Literacy in Taiwan

Fort Zeelandia on Taiwan

Fort Zeelandia on Taiwan© Marcel Tuit

From 1624 to 1662 the Dutch operated a trading post in Taiwan. It was called Fort Zeelandia, and was situated near modern-day Tainan. This functioned as a stopover for ships heading for Japan and as an entrepôt for the lucrative trade with China. Alongside VOC employees aiming to maximize profits, Dutch Reformed Church missionaries lived and worked in Taiwan. They attempted to proselytize the various indigenous peoples, and did so with some success. Robert Junius (1606-1655), who arrived in Taiwan in 1629 and left in 1643, learnt one of the local languages, Sinkan, and compiled a catechism in it. The Dutch set up schools where local people were taught the language. Sixty years after the Dutch had been expelled from Taiwan by the Ming loyalist Koxinga, a French missionary encountered Taiwanese on the island who could still speak Dutch. One important legacy of the Dutch presence was that it introduced literacy to the island’s inhabitants.

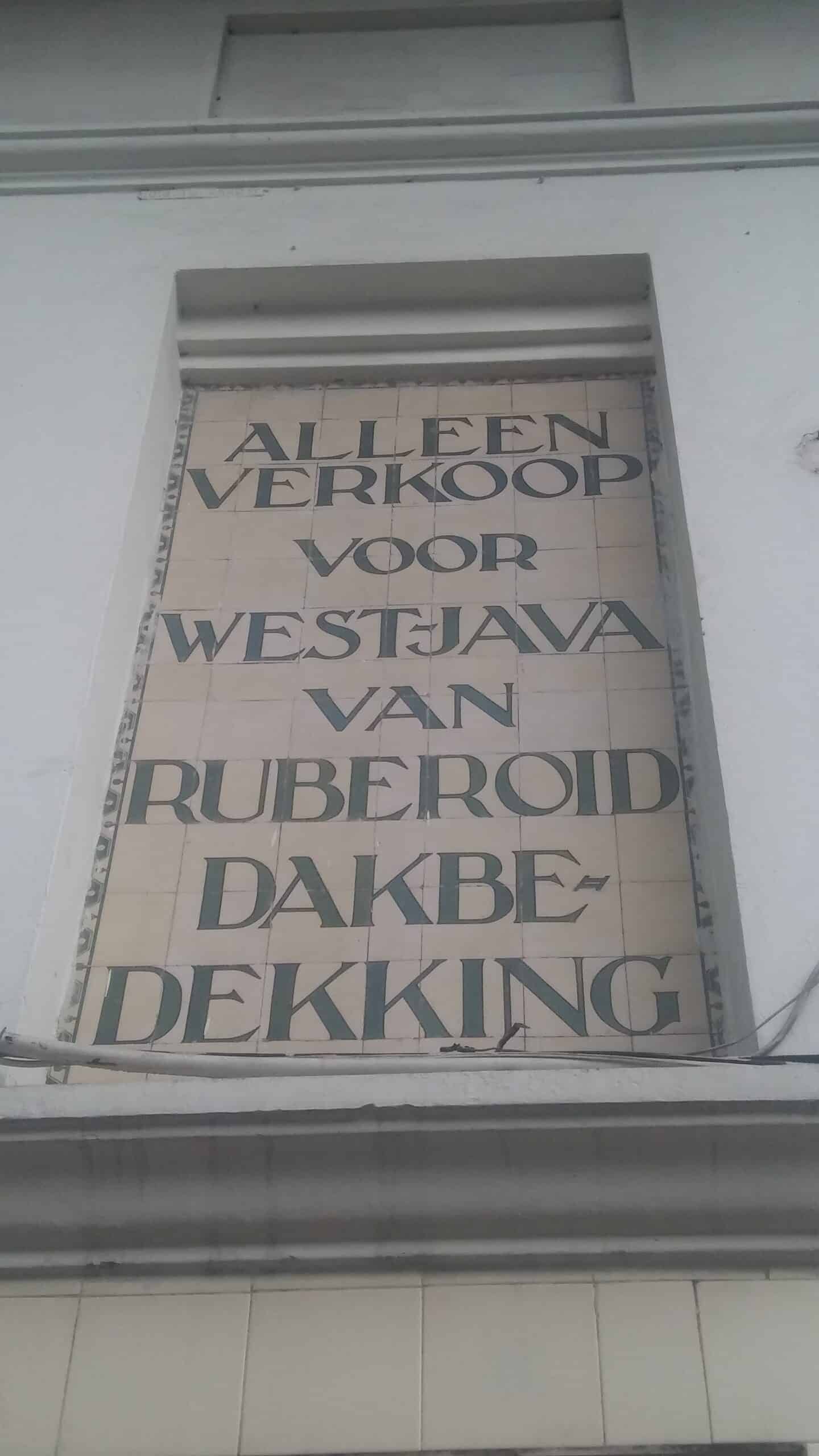

Shop in Bandung

Shop in Bandung© Christopher Joby

The VOC is most closely associated with the East Indies and with the town where the Governor-General resided, Batavia. Many Dutch settled in Batavia, establishing schools, churches and other institutions there. Some Governor-Generals and other VOC officials spent many years in Batavia. Anthony van Diemen (1593-1645) married his Dutch wife there, spending over a decade of his life as an employee and then Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. In the nineteenth century, as Dutch control spread out from Java and the Moluccas (the Spice Islands) to other islands in the East Indies, many thousands of Dutch migrated to the archipelago to work in business or administration, creating a European upper class in the colony. Some of course had relations with local people and a class of Eurasians emerged with mixed European and East Indies heritage. Estimates vary, but somewhere between 500,000 and 1,500,000 present-day Dutch are descendants of these Eurasians, sometimes referred to as Indos.

The Batavia town hall in the kota tua or Old Town of Jakarta

The Batavia town hall in the kota tua or Old Town of Jakarta© Christopher Joby

Influence on architecture and language

The Dutch influences on modern-day Indonesia are legion, including arguably the fact that such a country, made up of many islands and peoples with different cultures, exists. Two other influences to mention here are architecture and language. The Batavia town hall in the kota tua or Old Town of Jakarta still stands and today houses Jakarta History Museum. The summer residence of the Governor-General, Buitenzorg in Bogor near Jakarta, is now used by the President of Indonesia to entertain guests such as Barack Obama, who grew up in Indonesia. Many shops with Dutch signs in central Bandung have been preserved, witnessing to the commercial activity of Dutch immigrants during the colonial period.

Summer residence 'Buitenzorg' in Bogor

Summer residence 'Buitenzorg' in Bogor© Christopher Joby

As for language, both the language of wider communication in the archipelago, Bahasa Indonesia, and varieties of Malay such as Manado Malay spoken on Sulawesi and Ambon Malay spoken on the Spice Islands have many Dutch loanwords. In Jakarta, on a hot day, you’ll rush to the kulkas (fridge from the Dutch koelkast) and when driving in Jakarta you’ll be relieved to see the sign parkir gratis for free parking from the Dutch parkeren and gratis. And make sure you park correctly, otherwise the polisi may have a word! The Dutch etymologist Nicoline van der Sijs has identified more than 1,000 Dutch loanwords in Manado Malay, three hundred of which are not found in Bahasa Indonesia, and some 570 Dutch loanwords in Ambon Malay, for example ambtenaar (official), belasting (tax) and jaloers (jealous).

Indonesian 'polisi'

Indonesian 'polisi'In conclusion, although we may think of Dutch involvement in East Asia mainly in terms of trade, many Dutch who went there could more properly be termed migrants, who in some sense embedded themselves in local society. The consequence of the Dutch presence in East Asia can be felt to this day in many ways including architecture, place names and loanwords. The fact that many children were born to European and East Asian parents is perhaps sometimes overlooked, but their descendants form an important part of the rich tapestry of modern Dutch society.