Eastman Johnson, “America’s Rembrandt,” Was Nurtured by His Experience in Europe

Eastman Johnson (1824–1906), a leading American genre and portrait painter of the nineteenth century, was renowned for his authentic representations of uniquely American subjects. Yet reportedly he never picked up a paintbrush before traveling to Europe as a young man.

How did his early experience abroad shape his future success back home? The recently published Eastman Johnson Catalogue Raisonné, presenting his earliest to his latest paintings, prompts a contemporary look at his development. Following Johnson’s geographical and artistic journey, we can see the important contribution Europe made to his work and to the development of American art.

Judith and Harriet Johnson, 1845

Judith and Harriet Johnson, 1845Sotheby’s

Johnson already was a successful portrait draftsman by the time he left for Europe. Growing up in rural Maine, he taught himself to draw. As a teenager, he worked briefly in a lithography shop in Boston, then returned home and began to make portraits. Likely introduced by his father Philip Carrigan Johnson, Secretary of State of Maine, he drew prominent citizens in Augusta; he also traveled the state to make portraits, including those of Stephen and Zilpah Longfellow, parents of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Johnson’s drawing of his sisters Judith and Harriet demonstrates the high level of skill he had attained on his own by the age of 21.

In 1846 the elder Johnson became a clerk in the Navy Department in Washington, D.C., which literally opened doors for the younger Johnson. He was lent a room in the Capitol where he drew eminent Washingtonians including John Quincy Adams, Daniel Webster, and Dolley Madison. The same year, Longfellow invited Johnson to Boston to make portraits of himself, his family, and famous friends including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

In Boston Johnson met George Henry Hall, a young painter renting a studio in the same building. Hall wanted to study painting in Italy, but his patron Andrew Warner, Secretary of the American Art-Union, advised him to go to Düsseldorf instead. Relying on Warner financially, Hall agreed, and Johnson decided to join him.

Why Düsseldorf? There were few opportunities for formal art training in the States; to develop professionally and satisfy the tastes of sophisticated art buyers, an aspiring artist had to go elsewhere. Although one could study in Italy or Paris or England, at mid-century the “Düsseldorf style” was all the rage.

In 1849 John G. Boker, the German-born Prussian consul in America, had opened a gallery in New York to display Düsseldorf paintings he had brought there for protection from the Revolution of 1848. The Bulletin of the American Art-Union, May, 1849, hailed the Düsseldorf Gallery as “one of the most gratifying and instructive collections ever seen in the United States.” The art—primarily history, landscape, and genre paintings—was admired for its exacting design, subdued color, and finished look that showed evidence of formal training. The taste for this style lasted many years; as George Parsons Lathrop would recollect in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, April, 1893, “Thirty years ago the state of affairs in the New York world of art (a ‘world’ only by courtesy) might largely have been summed up in one word: Düsseldorf.”

Equally appealing was the nationalism of German art during a time of rising national pride in America. The American Art-Union actively promoted the creation and appreciation of American art through its Bulletin and exhibitions. Influential American cultural figures called for art and literature that celebrated their own land and people. The imperative for American artists was to paint American subjects and to paint them well. For a young country whose history was being made in its present, the Düsseldorf School set an example to follow.

Influential American cultural figures called for art and literature that celebrated their own land and people

In August 1849 Johnson and Hall sailed to Antwerp, staying a week before arriving at the Düsseldorf Academy. Their pilgrimage was shared by artists from many countries during the nineteenth century, including Belgium and the Netherlands. Although dozens of Americans would seek training there, Johnson was one of only a handful at that early date. The others included Worthington Whittredge, John Whetten Ehninger, Richard Caton Woodville, and German-American Düsseldorf Academy student and private instructor Emanuel Leutze.

Then directed by German Romantic painter Wilhelm Schadow, the Academy offered a rigorous program of study including examinations. The curriculum emphasized drawing and technical skill over color and expression. Johnson did not formally enroll, but took a class in Anatomy with Heinrich Mücke. His sketchbook (Brooklyn Museum), contains precise sketches and notations, including ideal proportions for the human body, that indicate a new sophistication.

More important to Johnson was the opportunity to learn from the collected expertise of teachers and students, including Andreas Achenbach, Ludwig Knaus, Otto Knille, and Bruder Elias Büsken. He made his first paintings by October 1850. In January 1851 he joined Leutze’s studio, where he worked with several other students on Leutze’s nearly 4 x 7 meter history painting Washington Crossing the Delaware (Metropolitan Museum of Art). He was assigned to make a small copy to be used for an engraving. Observing the methods of one of the most famous Düsseldorf School painters was a formative experience.

In the studio, Johnson was part of a community. He also was accepted into the artists’ association Malkasten (Paintbox). But by the summer of 1851, Hall had left for Paris and Leutze for America; he decided it was his time as well. Like Hall, he was disappointed by the prevailing constraints on color and ability to see only contemporary art locally. He considered Italy and Paris, but after a short trip to Amsterdam and London, he moved to the Netherlands.

Upon arrival in The Hague, Johnson began an independent study of the Old Masters at venues including the Mauritshuis, Six Gallery in Amsterdam, and Antwerp Cathedral. He wrote home enthusiastically about The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp by Rembrandt, and painted copies of Dr. Tulp and two other central figures. One can see that he was interested in the facial expressions, textural details, and ways in which light and dark could be manipulated for dramatic effect. He also made a copy of Rembrandt’s ‘Tronie’ of a Man with a Feathered Beret.

Johnson began to paint “types” in the spirit of Rembrandt’s tronies. An early example is his Old Waterloo Soldier, 1851.

Old Waterloo Soldier, 1851

Old Waterloo Soldier, 1851Christie’s Images

He made copies after van Dyck and contemporary Belgian artist Louis Gallait, but the work of seventeenth-century Dutch genre painters struck the most resonant chord. Rather than busy, emotional scenes by artists such as Jan Steen, he favored quiet dark interiors with few figures, like those of Gerard ter Borch. When he launched his painting career, exhibiting alongside Dutch artists in the Levende Kuntenaars (Living Artists) exhibitions of Amsterdam and Rotterdam in 1852, his subjects were genre subjects of the Low Countries: Een grijsaard, zijne kleindochter Christelijk onderwijs gevende (An old man giving his granddaughter Christian education), Twee Kaartspelers (Two Card Players), Die Vioolspeler (The Violinist), and Poort van een Kastel bij Winter (Doorway of a Castle in Winter).

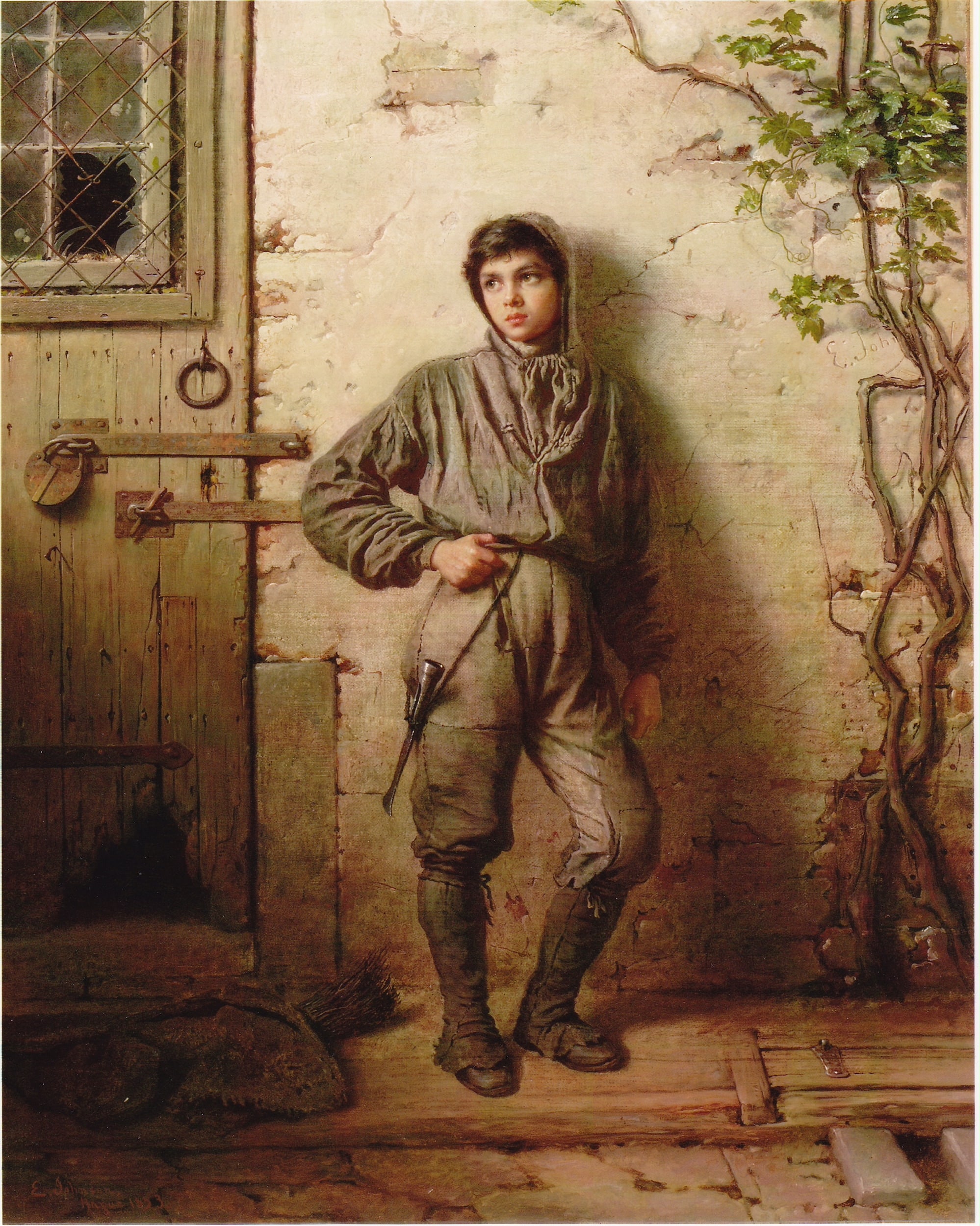

The Savoyard Boy, 1853

The Savoyard Boy, 1853Christie's Images

Other early paintings such as The Counterfeiters and The Savoyard Boy show that he was eager to put his German and Dutch learnings to use in both style and subject matter, and to appeal to popular tastes.

In 1853 in The Hague he exhibited his first American subject, Vader Tom en Evangeline (Uncle Tom and Evangeline). Harriet Beecher Stowe was touring Europe that year after the publication of her popular and controversial book Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Although the painting is now lost, Johnson clearly intended to appeal to his European audience while turning a spotlight on the specific, urgent problem of slavery in America.

Social connections continued to be fruitful for Johnson. He portrayed Americans George Folsom, chargé d’affaires to the Netherlands, ambassador August Belmont, and their families and secured other commissions. Ultimately he made nearly 40 paintings and drawings of distinguished men and their families in Holland.

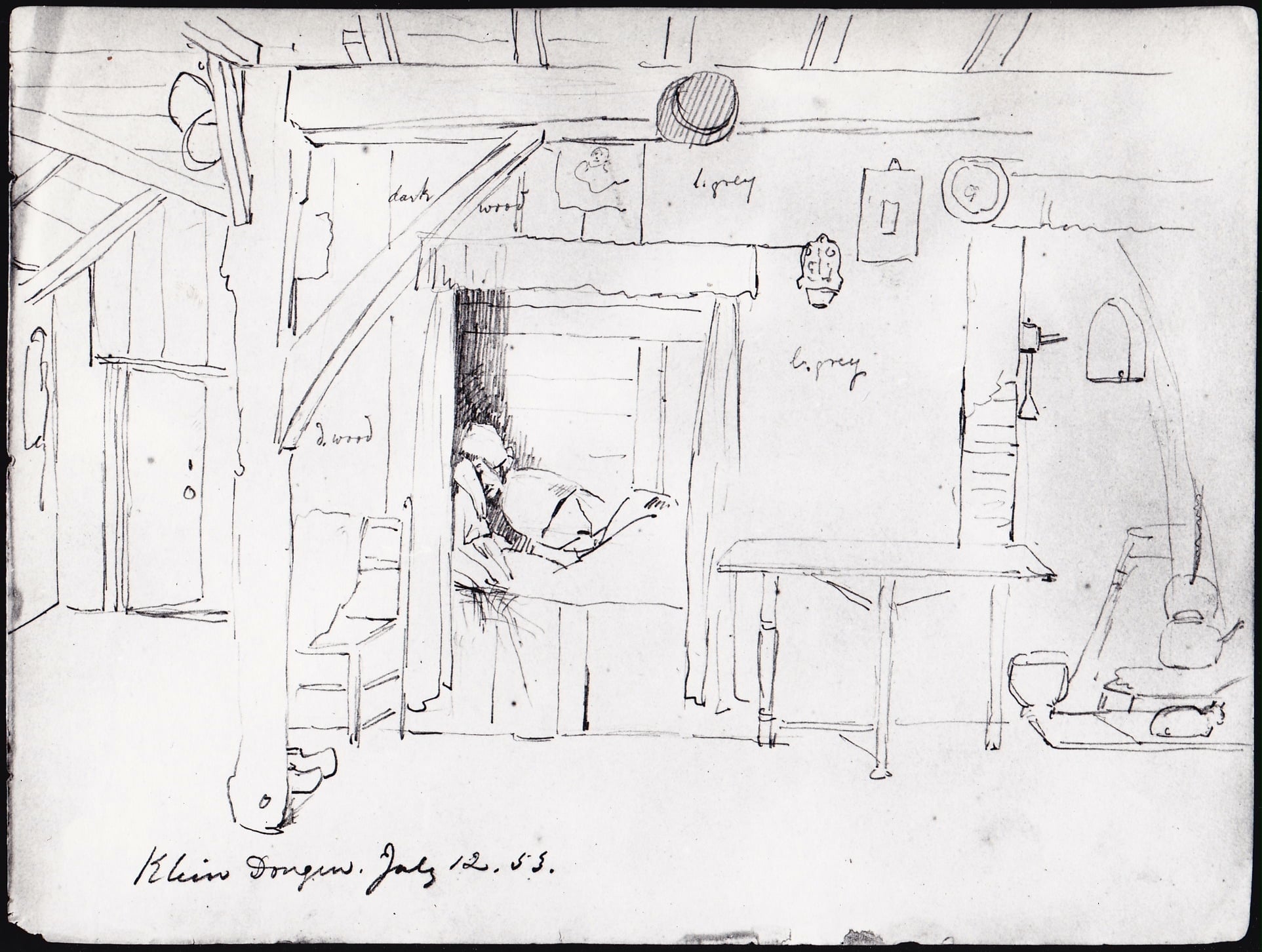

Surrounding areas of The Hague including Scheveningen and Dongen were fertile ground for sketching trips. Always interested in the “picturesque,” Johnson preferred people to landscapes. His Fish woman of Schaveninge [sic] shows his interest in local people and their customs. Interior of a Dutch Farmhouse, with color key, describes an intimate living space.

Interior of a Dutch Farmhouse, 1853

Interior of a Dutch Farmhouse, 1853Hirschl & Adler Galleries

At Mauritshuis Johnson would have seen Rembrandt’s self-portrait; he adopted the master’s practice of painting them throughout his lifetime. In his first dated self-portrait, 1853, Johnson presents himself with uncharacteristic drama in his new identity as a painter, looking forward seriously and directly, elegantly attired, holding his palette.

Left: Rembrandt, 1629. Right: Eastman Johnson, 1853

Left: Rembrandt, 1629. Right: Eastman Johnson, 1853Mauritshuis & Sotheby's

Johnson reportedly even was nicknamed “America’s Rembrandt.” Such a comparison must be taken lightly, but the nickname would have acknowledged Johnson’s earnest study of the master, his talent, and certain aspects of his technique, including his use of thin reddish-brown shadows and white impasto highlights.

In 1854 Johnson was accepted into the Pulchri Studio. He is rumored to have been offered, but declined, the position of court painter for William III of the Netherlands. In 1855 he moved to Paris, briefly joining the atelier of Thomas Couture before being called home by news of his mother’s death.

Johnson had benefited greatly from six years in Europe. In Düsseldorf he learned painting and the social aspects of an artist’s life. In Holland he absorbed the lessons of Rembrandt and Dutch genre painting and exhibited his work. Like other American artists who had gone and would go to Europe, he developed a new way of making art that he would propagate at home.

Back in the States, seeking the picturesque as in Dongen, Johnson traveled West to Wisconsin and Minnesota Territory to draw and paint the Ojibwe people. These works were for documentary purposes, a habit encouraged in Düsseldorf.

The first paintings Johnson exhibited in America were European genre subjects, including The Savoyard. But it was when he put what he had learned to use on American subjects that he became truly successful.

Negro Life at the South was exhibited to popular acclaim at the National Academy of Design in 1859, paving the way to Johnson’s election as an Academician in 1860. A scene of enslaved Black people and a white woman interacting in an enclosed yard, it is complex in composition and meaning. Critics delighted at the variety and specificity of individuals and activities unified within a harmonious tableau. On the eve of the Civil War, the image stirred partisan responses and interpretations based on viewers’ attitudes toward slavery. In the press the painting was compared to the work of Teniers; it was considered Johnson’s masterpiece. This was a scene he could only have made after his exposure to genre painting in Europe, but also could only have made in America, where the scene dealt with current events and was staged with local people in his neighborhood in Washington.

Negro Life at the South, 1859

Negro Life at the South, 1859Glenn Castellano/New-York Historical Society

So thoroughly did Johnson apply himself to American people and scenes that he often was praised for being little influenced by European art—yet its influence was plain to see. For example, The Young Sweep, 1863, recalls his European Savoyard of 10 years earlier, the sweeper updated and made more particular as a watchful Black child laborer during the Civil War.

The Young Sweep, 1863

The Young Sweep, 1863Detroit Institute of Arts

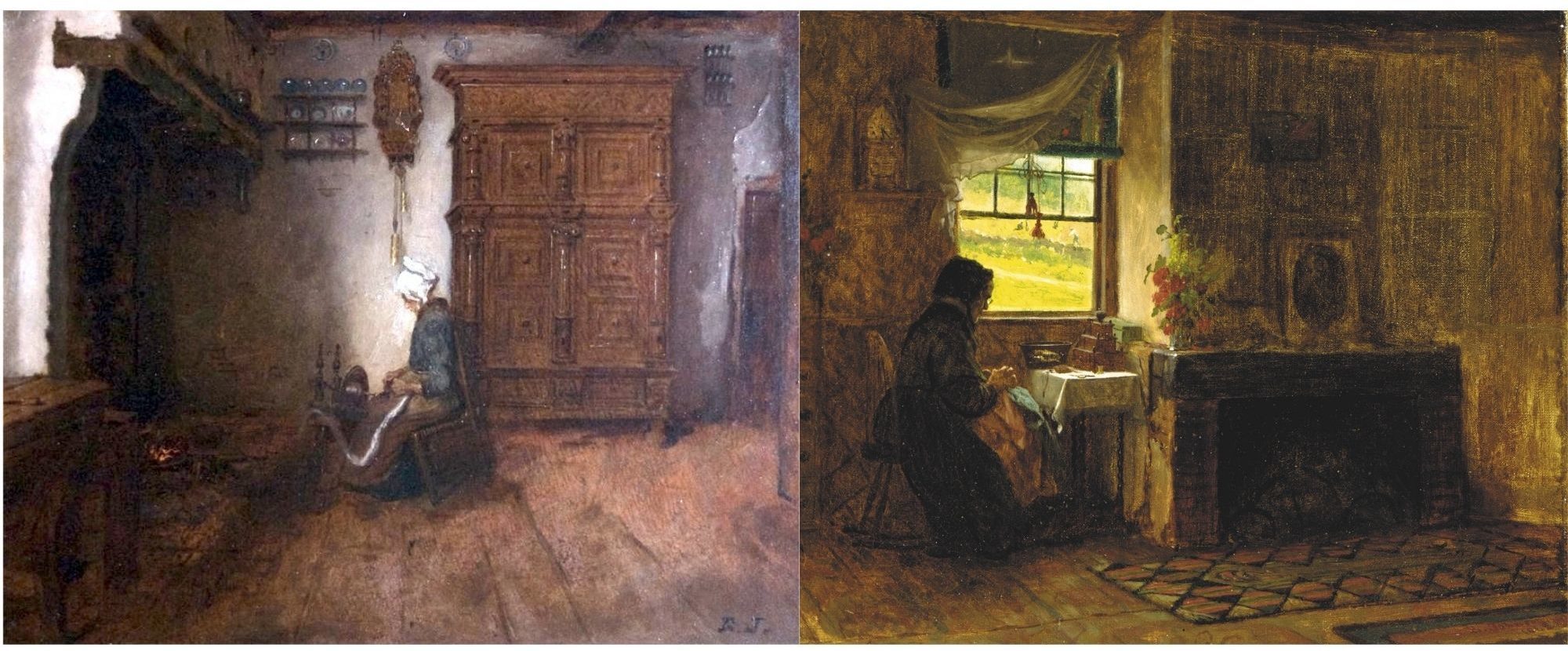

Johnson’s Country Home, 1865, echoes his Dutch Interior—Dongen, Province in Holland, c. 1853, with its dark interior, hushed mood, and solitary bonneted woman spinning or sewing. (The reuse of pictorial elements was a Düsseldorf practice.) Yet the cabinet in Dutch Interior is one that Johnson had purchased from the auction of the property of Willem II in Tilburg, and out the window of Country Home we see the rolling hills of Maine. Building on common human interests across an ocean, Johnson created a New England interior so familiar to Americans that a reviewer of Country Home in The Round Table, October 14, 1865, called Johnson “a true American singer, with not a note of Europe in his song.”

Left: Dutch Interior - Dongen (1853). Right: Country Home, 1865

Left: Dutch Interior - Dongen (1853). Right: Country Home, 1865Alexander Gallery & Christie's

He painted pictures of children, musicians, and rural people. He documented maple sugar harvesting in Maine in the 1860s and cranberry picking in Nantucket, Massachusetts in the 1870s. In Nantucket he also painted local sea captains and other residents as “types.” Johnson had produced exactly the kinds of genre pictures that had been called for decades earlier to advance American art.

Princess Marie of Holland, 1874

Princess Marie of Holland, 1874Irene Vlitos Rowe

In 1874 he painted a portrait of Princess Marie (Prinses Wilhelmina Frederika Anna Elisabeth Marie der Nederlanden), based on a drawing he had done in 1855 in The Hague. Why is a mystery, but suggests that his Netherlandish experience had stayed with him.

Increasingly in demand for portraits, Johnson made them almost exclusively after 1880, including those of four U.S. presidents. They were generally straightforward depictions, appreciated more for their dignity than psychological insight or technical flair. But he didn’t lose his affinity for Rembrandt. His last self-portrait, c. 1899, is his grandest. Costumed for the Twelfth Night celebration at the Century Association, one of the New York social clubs of which he was a member, the 75-year-old artist poses expansively in an elaborately draped chair. The rich color palette, strong chiaroscuro, and impasto used to describe the ruff at his neck, embroidered cuffs, and his own aging skin and facial hair model dramatically the now well-established artist to whom a younger generation of American artists was compared.

Self-Portrait, 1899

Self-Portrait, 1899Heritage Auctions

By the time he died in 1906, Johnson had become an artistic master of America’s Gilded Age, thanks in part to Rembrandt, the master of the Dutch Golden Age, and the traditions of European art that contributed so much to American art.

On July 29, 2021 – the anniversary of the artist’s birth – the Eastman Johnson Catalogue Raisonné (EJCR) was launched online at EastmanJohnson.org to share his works worldwide. The EJCR is directed by Dr. Patricia Hills and stewarded by the National Academy of Design. Browsing through Johnson’s paintings, one can see the development from his earliest paintings in Düsseldorf to his last in New York. Johnson’s drawings and prints will be added in the coming months to complete the presentation of the oeuvre of this distinctive American artist who, like many others, was nurtured by his experience in Europe.

The author is interested to learn more about works by Eastman Johnson held in European collections. Please contact her at eastmanjohnsoncatrais@gmail.com if you own, or know of, a work for consideration for the Eastman Johnson Catalogue Raisonné.

Sources and references for further reading:

- Patricia Hills, Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson, Garland Publishing, 1977

- Teresa A. Carbone, “From Crayon to Brush: The Education of Eastman Johnson, 1840–1858,” in Teresa A. Carbone and Patricia Hills, Eastman Johnson: Painting America, Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum of Art in association with Rizzoli International Publications, 1999