Ellis Meeusen: To all who read or hear this, salute?

Eighteen young Flemish and Dutch authors give a voice to an artefact from the Slavery exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Ellis Meeusen took inspiration from the 1863 law, drawn up by King Willem III, that set out the Netherlands’ official abolition of slavery in Suriname.

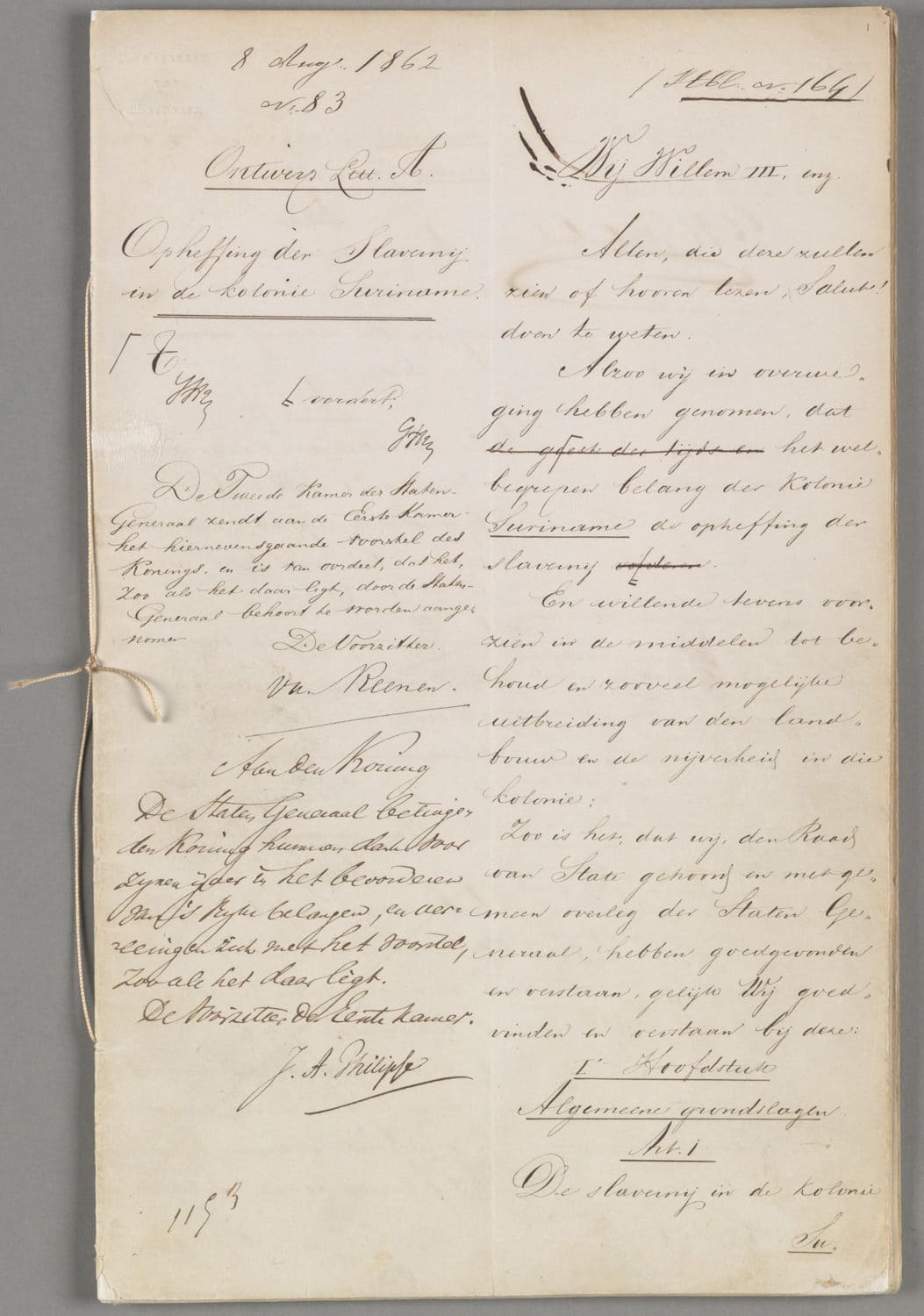

1863 law, drawn up by King Willem III, that set out the Netherlands’ official abolition of slavery in Suriname

1863 law, drawn up by King Willem III, that set out the Netherlands’ official abolition of slavery in Suriname© National Archives, The Hague

To all who read or hear this, salute?

There could have been something about love on here. On this paper, in this ink, in another hand, something or other about love. A hastily scribbled declaration of love, perhaps. Discreetly passed on, from closed hand to closed hand. Unfolded and read by candlelight. Just an example. And there may have been a reply. On other paper, in other ink, in another hand.

Or we could have had the signature of James L. Plimpton, who took out a patent on the quad roller skate on 4 January 1863. Or else that of Alanson Crane, who took out a patent on the fire extinguisher on 10 February 1863.

Or the signatures of sixteen representatives of just as many nations, who, on 17 February 1863, had just agreed to the foundation of the Red Cross.

Or the signature of Gerard Adriaan Heineken under a contract that formalised his purchase of Amsterdam brewery ‘De Hooiberg’ on 15 December 1863. Drawn up in two copies, his soon becomes sticky and unreadable because of accidentally spilt beer. But that does not matter, as it is merely the official confirmation of something that is widely known by now.

Or this could have been the birth certificate of Louis Couperus, dated 10 June 1863.

Or a page of the original manuscript of Jules Verne’s Cinq semaines en ballon.

Or a preliminary sketch for Le déjeuner sur l’herbe by Edouard Manet, a very tentative one, in pencil.

Or the death certificate, dated 2 December 1863, of Jane Pierce, the 14th First Lady of the United States of America, who will be interred beside her three little boys.

And at this point, you may be wondering why Jane Pierce is the sole woman in this list, alongside only men. Alongside only white men. If so, it is worth bearing in mind that this is not because of the women themselves, or the people of colour, but because of what is remembered via recorded history.

And you may be wondering, who writes this history. And is it correct? And who decides its value. And what, in this history, the significance is of a written law that promises freedom, which does not actually take effect for at least another ten years. Which promises freedom, yet at the same time specifies which songs not to sing. Who to give thanks to. Which is not written by those it represents. Which is not read by those it represents. Which is part of a history that does not make it into the school textbooks.

And perhaps you are wondering whether there should have been notes for a song on here. A song of hope and determination, a song written by those who will sing it, a song in which freedom is declared before freedom is granted. Only to be forgotten somewhere, in a trouser pocket, under a pillow. Because notes are unnecessary when freedom is already lodged in people’s minds.