Emile Claus’s Paintings Are a Pictorial Feast for Connoisseurs

Imagine a world where shadows are not grey or black but a vibrant explosion of deep purples, poison greens, and fiery oranges. Painter Emile Claus captured the elusive light by embracing shadows. One hundred years after his death, MUDEL, the Museum of Deinze and the Lys Region, celebrates the Flemish master of luminism with a magnificent and lavish retrospective. Artist Koen Broucke invites you for a tour of Claus’s fascinating oeuvre.

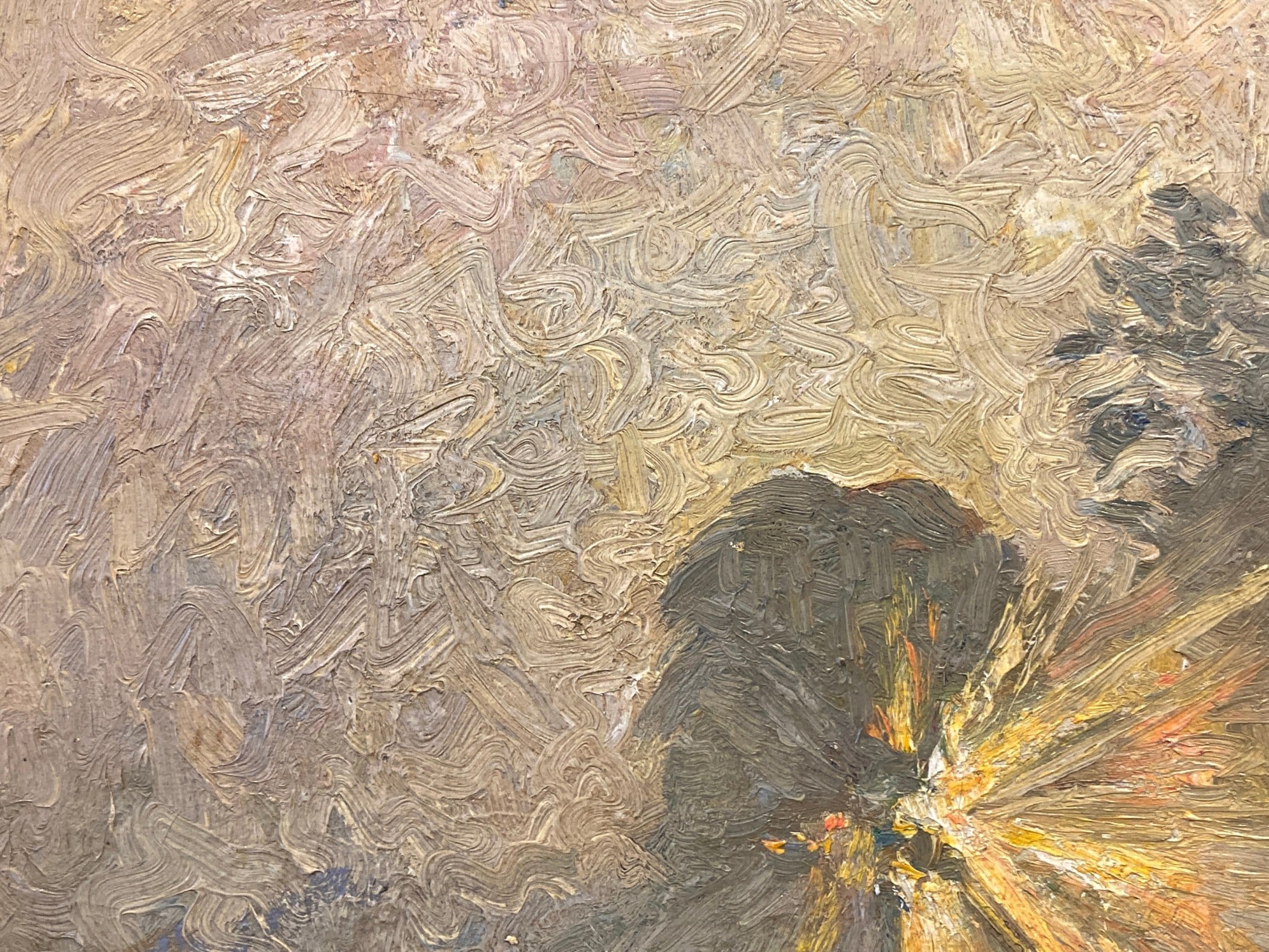

Let me take you, past Emile Claus’s early works, straight to the paintings from his best years and show you at random some of the shadowy areas. These parts are never black or grey, but an exuberant feast of colour and nuance, dark purple, poison green, deep blue, intense red and orange… They are composed of pointillist, energetic, intuitive brushwork. Each shaded part is an intense and festive world in itself. Indeed, these adventurous shadows alone are reason enough to justify the artist Emile Claus’s prominent role in art history.

Emile Claus, ‘Evening in June’, 1907

Emile Claus, ‘Evening in June’, 1907© Ministry of Finance

Belgian impressionism or post-impressionism

Light as such cannot be painted. Light dazzles, has no colour. At most, it would produce a monochrome canvas. However, light can be painted indirectly, depicted through the objects on which it falls and by working carefully on the shadows created by it.

In my opinion, this is the common thread running through Emile Claus’s work. Of course, the subject matter, the Lys region and the local peasants’ hard work, is also important. Claus studied in Antwerp, but as of 1882, he chose to live in the village of Astene on the banks of the River Lys. For a while, he returned to Antwerp during the cold winters, but he soon became enchanted by the winter splendour and the effects of the snow along the Lys and settled there permanently. Claus’s oeuvre is not a social indictment but demonstrates his empathy with the peasants of his time and his understanding for their hard work. In a painting such as Gathering Corn, (1894) he painted the poorest of the poor, but in attractive, warm colours in a pre-eminently bourgeois genre.

Claus’s oeuvre is not a social indictment but demonstrates his empathy with the peasants of his time and understanding for their hard work

Emile Claus is a representative of luminism, an art movement that is not easily defined. A sort of Belgian impressionism or post-impressionism, it adopted some techniques and knowledge bases from pointillism but is more playful and intuitive.

In 1886-1887 Claus painted his old gardener against the light. Backlighting offers an opportunity to depict the light in many ways: the transparent light that shines through the gardener’s apron, the light on the contours of the figure, on the hair and the sleeves of his gaping shirt, the rhythmical light on the shutters on the left, but above all, of course, in the shadow it casts. And that falls mainly outside the painting. Actually, as spectators, we stand in the shadow it casts, so that we become part of the painting. These shadows extend the paintings further and further to the surrounding environment, the environment in which we, as visitors to the museum, move.

Emile Claus, ‘The Old Gardener', 1886-1887

Emile Claus, ‘The Old Gardener', 1886-1887© La Boverie Museum, Liege

The same goes for the shadows of the trees on the wall of Villa Sunshine, a former hunting lodge that Claus transformed into a paradisiacal house with a garden on the banks of the Lys. He painted not the villa, nor the architecture, but the play of light from the surrounding trees. Those trees are partly behind us. Because there is not only the varied and colourful shadow of the trees on the house. There is also the shadow on the trees visible in the foreground. We come across this sort of long shadow for the first time on the large wall that takes up the whole of the left side of the painting The Communicants (Easter Sunshine) from 1883. The trees that cast these purple shadows must be somewhere to the right of us and the frame. As a result, the painting becomes immeasurably big.

This theme comes back often. In The Sky Lighting up over London (1918), one of the paintings that Claus made during his exile in London (1914-1919), we see the sun breaking spectacularly through the clouds. He almost literally repeats this effect and this cloudscape in After the Storm (1922), one of his masterly last works. During the war years, the artist fled to the United Kingdom where, apart from a short period in Wales, he worked mainly in London. He produced his top works from that period in a studio on the fourth floor of Mowbray House, with a view on the Thames that includes Westminster Bridge and Waterloo Bridge. He painted the fog, as Claude Monet and James McNeill Whistler had done before him, but again and above all the sun trying to break through the fog. The sun is veiled like a small compass, but always visible, like the hope for peace in the dark war years.

Emile Claus, detail from ‘Morning Sun’, 1904

Emile Claus, detail from ‘Morning Sun’, 1904© private collection, photo KB

‘The Strongest Worker in Flanders’

My fascination with the painter Emile Claus is not only to do with light and colour. In my opinion, you do not see such great variation in the brushwork of any other painter. First and foremost there is the very precise delineation and underdrawing with a fine brush and dark red paint. This is very clearly visible in the self-portrait from 1912 and the small, unfinished work Villa Sunshine. Then there are the virtuoso pointillist dots and commas, never dull, systematic, scientific, but always agile and intuitive. They go in every possible direction, rigid or supple, horizontal, vertical, diagonal… there are the long, elastic strokes – which may depict a branch in a single perfect stroke – and the whimsical, short arabesques. And then there are the smoothed areas, thin areas, solid areas, and so on. In short, a pictorial feast for connoisseurs.

Emile Claus, ‘Self Portrait’, 1912

Emile Claus, ‘Self Portrait’, 1912© Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

Emile Claus has painted an incredible number of brushstrokes. And they are all distinct. They are virtually never obscured in smoothed layers of oil paint. The speed, energy and nonetheless enormous precision with which the paint has been applied is striking. You can detect this speed very clearly in The Royal Pavilion in De Panne (1916), as well as in larger works, such as Beet Harvest (1890) and Cows Crossing the Lys (1897), in which the accumulation of millions of honest and visible paint strokes is downright breathtaking. In a note dated 15 January 1900, the writer Stijn Streuvels referred to the artist as ‘the strongest Worker in Flanders’.

Emile Claus, ‘Beet Harvest’, 1890

Emile Claus, ‘Beet Harvest’, 1890© Mudel

Thanks to the palette that is in the exhibition in Deinze and Claus’s testing of the light resistance of his oil paint (depicted in the catalogue) we can reconstruct the painter’s palette fairly accurately: burnt umber, burnt sienna, various shades of madder, cadmium orange, cadmium yellow, permanent green, emerald, ultramarine, cobalt blue, cerulean blue, ivory black, yellow ochre and, of course, a lot of white, white lead I assume and never unmixed, as art historian and lecturer Edmond-Louis De Taeye attested. James Ensor, never afraid to put down a colleague, wrote the following, ‘arrant reds, stately yellows, careerist greens, legal blues and impersonal pinks scream more falsely than ever.’ (From Réflexions sur quelques peintres et lanceurs d’éphémères).

Flowers, flowers, flowers

In the garden of Villa Sunshine stood majestic and distinctive trees. There was an orchard and a vegetable garden, the work of his wife Charlotte Du Faux. And there were many flowers: anemones, asters, azaleas, dahlias, hydrangeas, poppies, hollyhocks, California poppies, nasturtiums, wildflowers, and so on. Camille Lemonnier, a friend of Ensor and the author of the first monograph, was completely enchanted during his stays with the painter and wrote, ‘(…) a scent that shimmers in the early morning and dissipates in the light breeze from the curtains in front of the wide golden horizons. Claus painted these trees and flowers frequently and hedonistically. A Garden of Eden in oil on canvas.

There are various stories about the death of the painter, and there are different versions. Even Cyriel Buysse, one of Claus’s best friends, contributed to the myth creation and wrote a not entirely reliable version. But it is too good not to be true. On the morning of 5 June 1924, the good-humoured Claus was drawing a pastel of a bouquet that Queen Elisabeth had delivered to him to announce a visit to Villa Sunshine.

He signed the piece and added the date and time, which he otherwise never did (sic). He had barely finished it when he felt unwell. A doctor was sent for in haste. He diagnosed indigestion, nothing more. Just before three o’clock the pain lessened and, reassured, the doctor had apparently left, when Claus said suddenly,

– I have no pain anymore, but my chest is so tight, I’m short of breath.

Those were his penultimate words. Suddenly his head fell sideways, as if he were falling asleep. His lips barely moving, he murmured, three times in succession

– Flowers… flowers… flowers…

Then he said no more… and was still.

To this day, the pastel has not been found.

Emile Claus: Prince of Luminism, in MUDEL – Museum of Deinze and the Lys Region. Till 26 January 2025.

On the occasion of the exhibition, Hannibal Books has published a book on Emile Claus.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.