Emma Van Der Put Peels Her Images Back to Motionless Scenes

In Emma van der Put’s remarkable videos there is a constant tension between what moves and what is still or stopped. Van der Put is open to coincidence, but she understands that she is creating a selective version of reality.

In 2011 Emma van der Put (b.1988) depicted life in the Belgian town of Godinne from a hilltop. She did this in the holiday season, so the streets were almost empty, most residents away. When you look at the video Godinne, you quickly begin to wonder whether you’re looking at photos. But then there follows a shot of a dog crossing a street, or that motionless boy on the swing finally moves after all and the picture briefly seems to thaw. Due to the lack of action, you have the concentration to track down such tiny details, which within the static shot almost gain the allure of a grand event – thanks to coincidence.

Still from Godinne (2011)

Still from Godinne (2011)© Emma van der Put / tegenboschvanvreden, Amsterdam

Filmmaker as eye

When filming or taking photos, Van der Put’s main aim is to feel like an eye. The most important thing is that she is open to coincidence, to what might play out at that moment: a neon advert reflected in a large poster of a piece of meat, for example (Room, 2014). As she films, she feels like an outsider, prohibited from or incapable of intervening. She notes that film is a medium that steers the viewer’s gaze, one that is at odds with the early phase of the creative process, which should really be as detached as possible.

Still from Room (2013)

Still from Room (2013)© Emma van der Put / tegenboschvanvreden, Amsterdam

The steering happens during the editing phase. She watches the material she’s shot in a more analytic manner, selects what she will use from it (less than 10 percent makes it into the final video), and decides the order and pace of the images. She often leaves a moving or still image “hanging” for longer than many viewers are accustomed to, their habits formed by fast-paced TV series, films and video clips, or the museum visit, where you decide for yourself how long to look at a painting. You could also say that the editing sets a time limit on the scenes, depriving you of the possibility of looking for as long as you want. But in Van der Put’s work, those two options – transience and extending the moment – needn’t be mutually exclusive, as you see even more clearly if you dive into her earlier work.

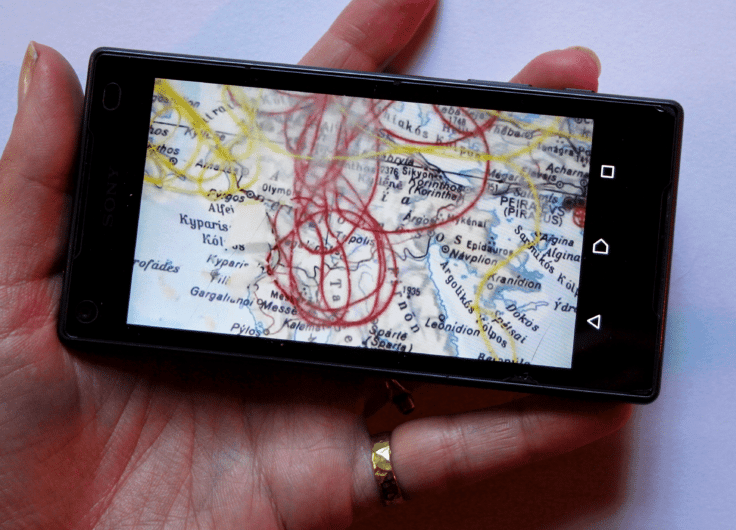

Emma van der Put

Emma van der Put© Nucleo

One of the recurring themes of her oeuvre is the friction between movement and ‘standstill’. In Fountain (2014), for example, you see the fountain water running in front of the hands and faces of two statues of naked children gripping one large fish, creating a prominent contrast between a static background and a moving foreground. This contrast is also strongly expressed in the images which Van der Put has shot in public, which may seem like fleeting visual impressions and yet appear to freeze briefly or stretch the moment, as in the almost photo-like shots of Godinne.

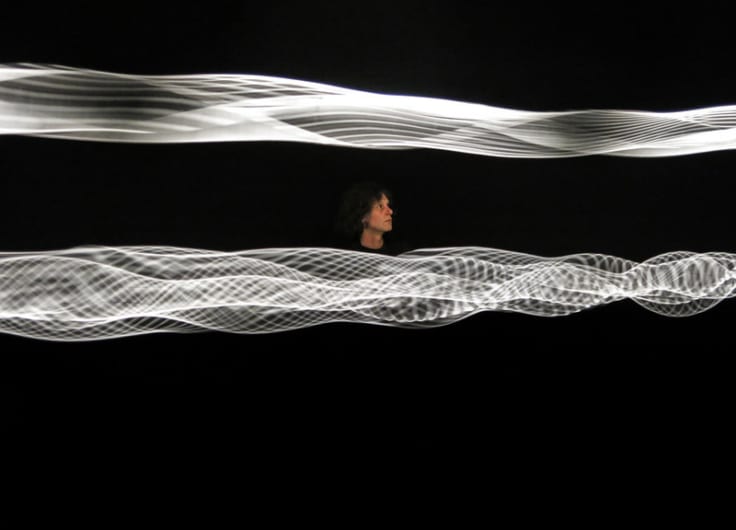

Still from Fountain (2014)

Still from Fountain (2014)© Emma van der Put / tegenboschvanvreden, Amsterdam

Her videos have no literal narrative structure, let alone a voice-over to supply text and explanation. Where she works with sound at all, it is atmospheric background noise, at most some sounds, but never pointing to the kind of interpretation of events you would expect of a TV-series. You have to make the effort yourself, particularly when you unsuspectingly walk into the room mid-video. Watching and understanding are closely bound together in these videos. On this subject, Van der Put remarks that in the editing phase she tries to invoke a feeling comparable to sitting on a bench, really looking around you and thus slowly beginning to gain an increasing understanding of the surroundings.

The public setting

Public spaces also play an important role in Van der Put’s oeuvre. She sees them as a kind of theatrical setting which largely shapes the way people behave in that environment. For early videos, for instance, she filmed the Maritime festival in ’s-Hertogenbosch (Scènes of an evening and Maritime Festival, 2009 and 2012), or an Amsterdam fair (Funfair, 2012). Later this interest also emerges more frequently in her work, in advertising posters, graffiti and other public messages, as well as in the history of the location: the context which effectively communicates the rules of the environment and often shapes them as well.

Stills from Scènes of an evening (2009) and Funfair (2012)

Stills from Scènes of an evening (2009) and Funfair (2012)© Emma van der Put / tegenboschvanvreden, Amsterdam

This fascination is also clearly expressed in the videos she has made since the work WTC (2016). In these she records the life of the surrounding area from above, from one of the World Trade Centre towers in Brussels: people going to work or crossing the street, the modernist architecture characteristic of the area, refugees sleeping in the streets. She also took photos of archive material such as posters and building plans, which could still be seen in the towers and which bore witness to grand plans for the area where eight WTC towers were to be built. Due to troubles with fraud and lack of investors only half were ever actually built.

Still from WTC (2016)

Still from WTC (2016)© Emma van der Put / tegenboschvanvreden, Amsterdam

That turbulent history is part of a much larger phenomenon which has occupied Van der Put in recent years: the confrontation between the optimistic, modernist future thinking and the daily reality in Brussels, where she has worked since 2014. Although she still has an eye for the moment, in these videos of Brussels she deliberately takes plenty more time to shoot images so that she can get to understand the city and her locations ever better and can observe with as few preconceptions as possible.

One of the videos is Mall of Europe (2018), which remains on show until 21 June 2020 in Mu.ZEE in Ostend. Mall of Europe revolves around the district of Heizel, outside the city centre. The famous World’s Fair Expo ’58 was held there, and not long after World War II, the near future was presented with hope. Ironically enough the area is now in need of thorough renovation. In the plans, again, a modernist optimism is discernible, Van der Put notes, but the earlier ideas about progress certainly haven’t all been implemented as intended.

The friction is also concisely expressed in the short video loop SOON (2018), which endlessly shows an advertising board promising new office buildings. The two letter Os in the word soon form an infinity sign, and the longer you look, the less you believe that the promise of the word will be fulfilled.

Still from SOON (2018)

Still from SOON (2018)© Emma van der Put / tegenboschvanvreden, Amsterdam

Nevertheless, these videos recently found a more optimistic counterpart in Westland Shopping (2020), in which Van der Put records how a decaying shopping centre is used by consumers on Sundays as a space for a flea market. In this way, they undermine the classic idea of such a building – enabling people to continually buy new products.

Peeled image

The work WTC also marks the point at which Van der Put began to make videos in which she was not working with a moving image but was effectively creating still photos. Due to the tower perspective, WTC, in particular, is reminiscent of the high camera viewpoint in Godinne, but the big difference is that movement has crept in unexpectedly, something which is at most suggested in the photo videos. She takes the friction between frozen moments and fleeting impressions so exquisitely to extremes: dynamic street scenes are paused and muted. Suddenly those often screechy scenes are peeled away to an image that is still in multiple ways and invites us to look.

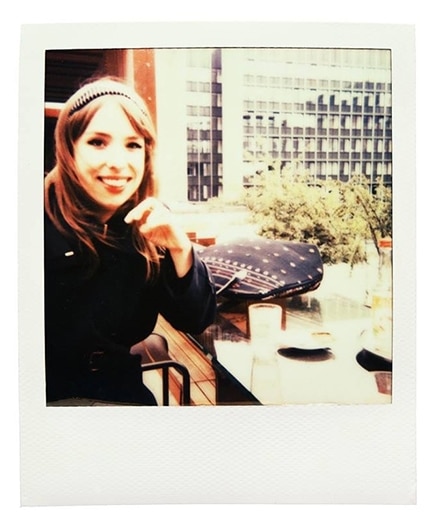

Still from Westland Shopping (2020)

Still from Westland Shopping (2020)© Emma van der Put / tegenboschvanvreden, Amsterdam

But just when you think you’ve explored the image, it becomes clear that the entirety can be far more mysterious. You might be inclined to see flea markets in Westland Shopping as hopeful, but there is a good deal of attention for the cold concrete of the building. Or is that just the place for such an initiative?

Mall of Europe remains on show until 21 June in Mu.ZEE (Ostend).