Encounter at the Crossroads of Europe. The Fellowship of Zweig and Verhaeren

Stefan Zweig was one of the most famous writers of the 1920s and 30s. British poet and translator Will Stone explores the importance of the Austrian’s early friendship with the oft-overlooked Belgian poet Emile Verhaeren.

Friendship stands highest on the forehead of humanity…’ – Keats

I

While still at school, Stefan Zweig had tried his hand at translating a number of French and Belgian poets, Verlaine, Mallarmé and Baudelaire, but also another name almost unknown to us today, Emile Verhaeren. Something about the elemental nature and incendiary vision housed in the rugged and unorthodox language of the Flemish born Verhaeren resonated with the youthful Zweig, jarring somehow with the comfortable, ordered cultural advancement of his existence, where the restless wanderings of later life were calmly incubating. Zweig’s own work in these early days seemed about to follow a very different course. As is well known, Zweig came from a privileged Jewish bourgeois background in Vienna, the intellectually buoyant yet self-regarding metropolis at the heart of the sprawling Hapsburg kingdom, where the young Zweig was liberally steeped in art, literature and music from an early age. In Vienna, Zweig maintained good relations with his parents after completing his schooling, but immersed himself completely in the Viennese café lifestyle of a writer, a period in which he learned the importance of personal freedom through wide-ranging dialogue with diverse artists and literary figures. This formation period was where Zweig’s undying thirst for wider travel and experience of the foreign was seeded. But as the century turned, Zweig was absorbed with his coming of age literary achievement, the publication of a first collection of poems at the tender age of twenty-one.

Silberne Saiten (Silver Strings) was well-received and unlike most first efforts by a newcomer, found favour amongst Vienna’s critics, even one Rainer Maria Rilke responded gratefully to his copy, by sending Zweig a dedicated book. Yet these ‘smooth, able verses’ yielding to accustomed versification were as Zweig soon realized too much of a borrowing, a reconstituted product of a time and place, or more aptly of a time that had now passed, but was still hanging on in the Viennese literary salons, like incense in a nave, a stale fragrance which the gathering wind of modernity was soon to brutally disperse. Although this book brought Zweig’s name into the limelight for the first time, it served as a temporary shackle, which he sought to remove at the earliest opportunity. When Zweig left for Berlin and university in 1902, he left Vienna as the most prominent of the younger writers, an overnight success, but in essence he had not yet even begun.

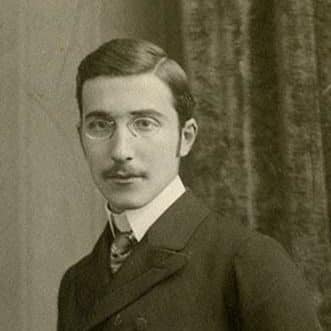

A young Stefan Zweig, around 19 years old, circa 1900

A young Stefan Zweig, around 19 years old, circa 1900© Wikimedia Commons

In Berlin, apart from his studies and bohemian indulgences, Zweig sought a more expansive freedom in literary terms, and caught the bug of translation. He began to explore further afield, even translating poets such as Keats and Yeats and producing with other translators a collection of Verlaine’s poetry to which he added a critically acclaimed introduction. But all the time he was moving closer to Belgium, drawn by the rich crop of its homegrown artists and writers who seemed to integrate their works in fresh and creatively productive ways. So in the summer break of 1902, long anticipating a visit to the ‘little land between the languages’, Zweig made his move.

Verhaeren had come onto his radar while still at school, when he found a copy of the poet’s first Rubenesque collection Les Flamandes (1883) and instinctively attempted a clutch of translations. He had even written to Verhaeren in 1898 to secure permission to publish them in a journal. Now, he was determined to meet the man himself, though it was the novelist Camille Lemmonier, to whom Zweig had recently dedicated an essay, whom he first located in Brussels. Zweig had sent a postcard in rather shaky French to Verhaeren suggesting a meeting, but it was unclear when Zweig arrived in the Belgian capital if this rendezvous would come to pass. On arrival it seemed that Verhaeren was away and Zweig’s hopes were dashed, but by a fateful stroke, Lemmonier then invited him to meet the sculptor Charles van der Stappen, and Verhaeren just so happened to be in the sculptor’s studio sitting for a bust. Zweig’s memories of that first crucial encounter with the older man are pertinent.

For the first time I felt the grasp of his vigorous hand, for the first time met his clear kindly glance. He arrived as he always did, brimming over with enthusiasm and the experiences of the day…It seemed as though he projected his whole being towards you…he knew as yet nothing of me, yet already he was full of gratitude for my inclination, already he offered me his trust just because he heard I was close to his work. In spite of myself, all shyness faded before the stormy onset of his being. I felt myself free as never before, in the face of this unknown, open man. His gaze, strong, steely and clear, unlocked the heart.1

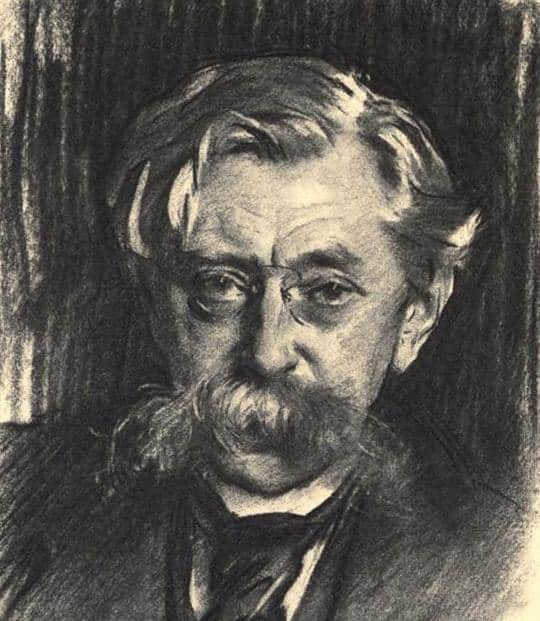

Portrait of Emile Verhaeren in 1915 by John Singer Sargent

Portrait of Emile Verhaeren in 1915 by John Singer Sargent© Wikimedia Commons

The vital importance of Zweig’s meeting with Verhaeren in relation to his ensuing career as a writer, emissary of humanism and key proponent for the higher ideal of a Europe of cultural unity, cannot be underestimated. The contrast between Verhaeren’s openness, curiosity, vitality, not to mention the explicit visionary credentials he held, and the self-conscious dandified Viennese poetry circles Zweig had moved within was extreme. It was if Zweig himself had suddenly been released from a reserve of pampered elites into the rawness and unpredictability of the wild and could finally breathe real air, taste real food and appreciate the creative potential of risk and unpredictability. In Verhaeren’s verses he saw bold new vistas opening up which seemed to strike a necessary chord with the rapidly transforming epoch, as the fabled ‘golden age of security’, guarded by the Hapsburg realm unceremoniously gave way to something far more restless, ominous and uncertain.

The time demanded a new poet to express its infinite variegations and Verhaeren was evidently the best man for the job according to Zweig, the only one who was prepared to face the new century eyes wide open, a poet who had proved himself wholly authentic and not tainted by any school or movement, who was implicitly true to himself and those around him, a man who wilfully absorbed everything lucidly and without compromise, whatever the cost to his mind and health. Zweig’s almost priest-like dedication to Verhaeren was long-standing and never wavered. Of the most important men of example in his life, Verhaeren was the most significant. Following Zweig’s crisis after the upheaval of the First World War, Romain Rolland assumed this role, but this was an altogether different entente cordiale for which there is no room here.

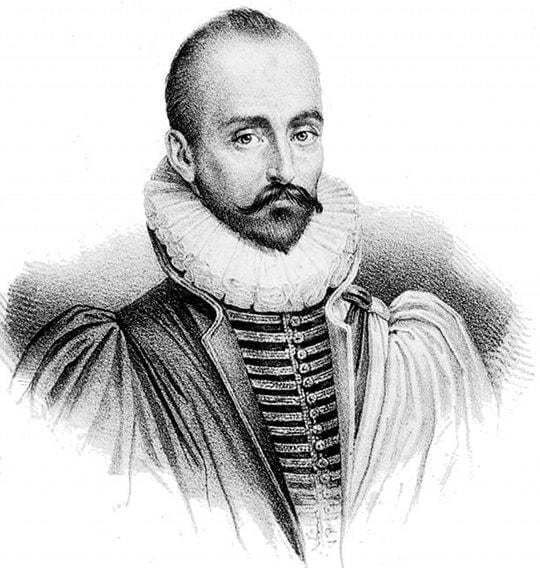

The third key master, was the great essay writer Michel de Montaigne, who appeared from the wings as a timely ghost at the close of Zweig’s life, in order to philosophically assist with Zweig’s departure from the world at what was judged the right moment for him. Montaigne closes Zweig’s story, addressing him personally from across five centuries. More than Balzac, Tolstoy or any of the others ‘greats’, it is Montaigne who comes to his aid at the eleventh hour, Montaigne who manages to complete the circle of the men of example. Montaigne shows a desperate and morbidly depressed Zweig, hounded from one country to another, and convinced Europe has finally destroyed itself, an ethical way out of the mental inferno through his essay of vivid historical examples, ‘A Custom of the Isle of Cea’.

Portrait of the 16th century essayist Michel de Montaigne

Portrait of the 16th century essayist Michel de Montaigne© Wikimedia Commons

Zweig’s literary output is prodigious and notably varied. As well as proving himself a gifted short story writer with Amok and Buchmendel amongst others, and an accomplished novelist with Beware of Pity, Zweig was also the great portraitist of major artists, historical figures, legendary writers and explorers, his books being read in greater numbers than any other German-language writer through the 1920s. But these were never dry academic studies or even biographies per se, but more lyrically borne psychological plumbings around the nature of the subject, the archaeological digging for spiritual affiliations which guaranteed the subject their boarding pass to Zweig’s European ark on the Kapuzinerberg in Salzburg. Zweig, always modest about his own achievements and ultimate legacy as a writer, despite his popularity, seemed compelled to serve, possessing an insatiable need for masters, or fraternal figures to whom he could signal, that writerly kin greater than himself, who set the standard to be judged by, monumental figures like Tolstoy, Balzac, Dostoyevsky… and those figures in history who related to his own predicament in the greater predicament of Europe, such as Erasmus and again Montaigne.

All these long-dead artists and those still living, were for him crucial sources of personal reassurance at moments of doubt and weakness, examples of nobleness in endeavour, personal sacrifice to art, a reliable crew of patient toilers and visionary explorers. Zweig wanted to collect them all, experience them to the core, and penetrate their secrets, not to ‘consume’ them so to speak, to line them and gloat as a collector of figurines, but to celebrate the spiritual thread of each, which when woven together constituted the unique European consciousness of which he was a guardian. Not only did Zweig excel as a determined collector of manuscripts, scores, letters and memorabilia of Europe’s finest creators, but he collected them in his head as compass points, a series of safe harbours to which he could moor up to sit out the storm, where he could replenish his supplies of fraternity and find the spiritual hospitality he craved. It was Verhaeren, the living man, Nietzsche’s ‘Good European’ who personified this greatness for Zweig, the older Belgian poet whom Zweig encountered on the cusp of the former’s maturing renown, a renown which Zweig himself was personally committed to deepening and upholding.

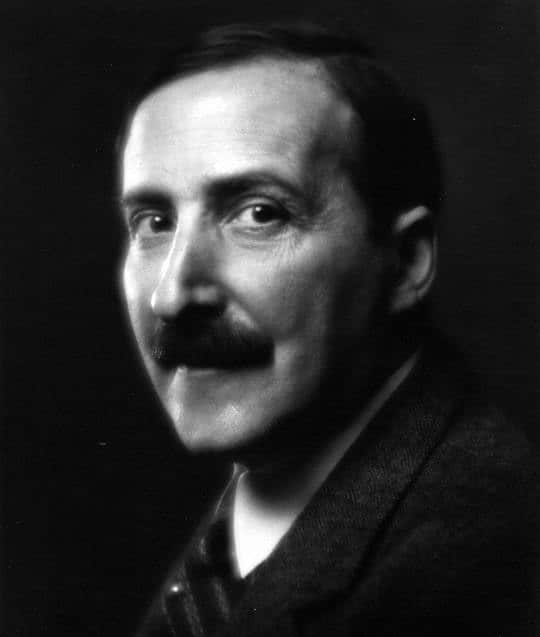

Photograph of Stefan Zweig from Fayer via Stefan Zweig Centre, University of Salzburg

Photograph of Stefan Zweig from Fayer via Stefan Zweig Centre, University of Salzburg© Stefan Zweig Centre, University of Salzburg

Over the coming years, Zweig’s close friendship with Verhaeren was consolidated and he was customarily invited to spend part of the summer with the poet and his painter wife Marthe Massin at their idyllic country cottage at Caillou-qui-Bique in southern Belgium. In the decade before the First World War, Zweig took it upon himself to firmly establish Verhaeren’s reputation in Germany, where hitherto Verhaeren’s exposure had been weak. He himself embarked on a marathon translation of a selection of Verhaeren’s poems and through his by now impressive contacts, managed to secure a prominent publisher, so that Verhaeren’s work, backed up by carefully organized reading tours of major cities, began to spread rapidly through Germany.

Verhaeren benefited greatly from the German ‘surge’, in terms of his European profile overall, and all through Zweig’s diligent efforts. Zweig became the ambassador for Verhaeren’s voice and made sure it reached the leading literary circles of the continent, so that by the time of the Belgian poet’s untimely death in 1916, it would be true to say his influence had spread as far as Moscow, with the likes of Blok and Mayakovsky taking an interest and furthermore Verhaeren was in demand on the lecture circuit, for his exuberant delivery, the torchbearer of a new kind of poetry which, like Walt Whitman in America sought to engage with nature at an elemental level.

Whitman’s famous ‘Look for me under your boot soles’, would seem equally apt for Verhaeren, the terrain being Flanders, though the Belgian poet, as Zweig realized, and expounded with fervent persuasion in his biography Emile Verhaeren (1910) had gone much further than Whitman, probing into the destructive excesses and social implications of industrial change and the decimated rural landscapes which were its legacy. For example in his major work Les Villes tentaculaires (1895) Verhaeren optimistically envisages some potential metaphysical transcendence for mankind out of the crucible of power engendered by the frenzied activity of the new urban multitudes and the delirious energy of the blast furnaces.

II

But everything changed with the war. Optimism and idealism were the first casualties, ignominiously swept away, never to return. Ironically, and fatefully as ever, Zweig was on his way from Ostend to visit Verhaeren at Caillou in the late summer of 1914, just as Europe’s borders started to freeze. Only weeks before, Zweig had met the Insel editor Kippenberg, along with Rilke, Rolland and Bazalgette in a café in Paris to discuss the prospect of a Verhaeren ‘Collected Works’, a series of volumes comprising all his poetry to be published in 1916 as a surprise gift to the poet they all admired so deeply. Zweig himself would take on La Multiple Splendeur (1907) and each was allotted his task to find suitable translators.

The project was stillborn. Seemingly out of nowhere, nationalist hatred had engulfed Europe and such noble schemes became but a forgotten trifle of literary history. The friends were forced back to their respective native lands and detained there for the next four years through the great ensuing international convulsions, their high-minded fellowship for European artistic integration temporarily disbanded. At the end of August 1914, Zweig himself, having hung on to see which way the axe would fall, was hurrying at the last minute from Ostend, due to meet Verhaeren for his annual sojourn at Caillou. He was forced to turn back as mobilization engulfed the area, taking the last train from Brussels across the border into Germany, or risk being detained as an enemy alien, a fate he was absurd to incur later in Britain in 1939. The two men were never to see each other again, nor were they even to communicate.

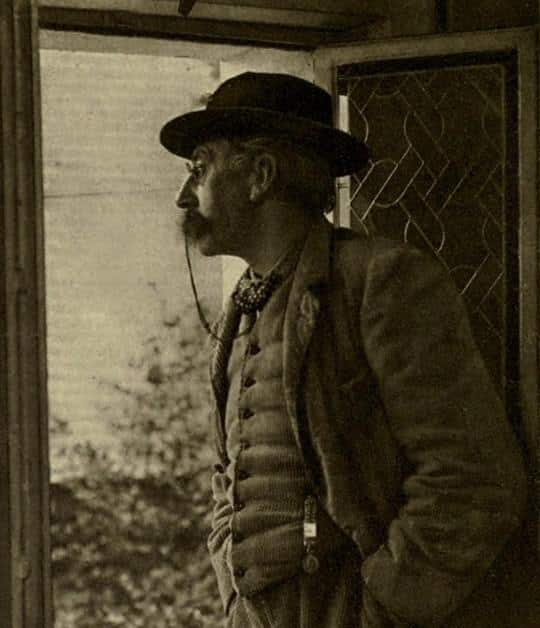

Photograph by Charles Bernier taken in 1914 of Verhaeren from the frontispiece of the 1914 English translation of Zweig's Emile Verhaeren

Photograph by Charles Bernier taken in 1914 of Verhaeren from the frontispiece of the 1914 English translation of Zweig's Emile Verhaeren© Wikipedia

As former friends were suddenly confronted with the prospect of being national enemies, tensions and uncharacteristic behaviour threatened once solid and seemingly unshakeable bonds. Almost overnight the old Europe of freedom of movement and tolerance was annihilated and would only return post-1918 as a disabled version, mortally infected with fresh unrest mutating out of the old. Verhaeren, who had always been a profound admirer of German art and had travelled to Germany as a younger man on lengthy visits for the express purpose of becoming better acquainted with its art, he who had latterly known German acclamation at the hands of Zweig, now sank into a bitter hatred of the foe, after the Teutonic fury unleashed throughout his beloved Belgium.

The destruction of Namur, the obliteration of medieval Ypres, the gratuitous murder of civilians, the sacking of Louvain and willful burning of its priceless antiquarian library by German troops, seemingly ordered to lay waste to Belgium, pushed Verhaeren over the edge into a blind hatred of the Prussian ‘barbarians’. The result was La Belgique Sanglante (Belgium bleeding) an ill-starred though understandable ranting diatribe against everything German, a book which became little more than a propaganda coup for the allies. Now wincing to read, it served at the time to enhance Verhaeren’s new figurehead status as Belgian national poet allied to the king. This ‘official’ position he never really wanted, but was saddled with and the rhetoric and pomp which attaches itself to such positions may to some extent may explain in part the velocity of his post-war decline.

Zweig, himself the ‘confused’ victim of an initial hot-headed rush of national pride, (something he attempts to gloss over in Die Welt von Gestern (1942)) was shocked by Verhaeren’s seeming personality change, this sudden explosion of hate being the complete antithesis of all he had stood for. The rude shock of world war had ripped through the ideal. Normally noble-minded men were scurrying for cover into patriotism, following the nihilistic onslaught of undiscriminating death and destruction. Romain Rolland stood alone in Switzerland, trying to gather the dispersed pacifists about him. Zweig put out feelers to Verhaeren, hoping to rekindle the flame, but draconian censorship did not help and the line stayed dead.

Eventually as the war dragged on into a perverse contest of attrition, the red mist began to lift and Verhaeren reclaimed his lucid self. He sought to weaken his previously entrenched stance vis a vis the Germans, but somehow the line of communication with his most faithful servant Zweig was never repaired and Verhaeren died tragically in November 1916, accidentally crushed by a train in Rouen station after giving a patriotic speech to Belgian exiles.

Photograph form 1927 showing the removal of Verhaeren's remains from Wulveringem near Veurne to be taken and reburied in his home village, on the banks of the Scheldt, as he had requested.

Photograph form 1927 showing the removal of Verhaeren's remains from Wulveringem near Veurne to be taken and reburied in his home village, on the banks of the Scheldt, as he had requested.© Wikimedia Commons

The true nature of the loss of Verhaeren, the cruel severing of this fellowship by the war, was vividly expressed in Zweig’s moving personal tribute Errinerungen an Emile Verhaeren, published in Vienna in 1917. Here Zweig tries to cauterize the open wound left by Verhaeren’s passing and the final silence between them that was never assuaged. How much Zweig longs for a different ending, in his lamentation you sense so keenly the sense of something unfinished in the emptiness left behind. And yet by indulging in such painful reverie, and acknowledging the death, Zweig unconsciously summons the ghost of his friend, whose replenishing spirit enters into him with ever more vital insistence.

A dark day, I still remember it now and will never forget. I took out all his letter, his many, many letters, all of them there in front of me so as to read them again, to be alone with them, to bring to a close what was now finally ended, for I now knew I would never receive another. But there was something in me which refused to say goodbye to something that lived in me like the incarnated proof of my own existence, of my faith on this earth. And the more I told myself that he was dead, the more I felt him breathing his life through me and even these words with which I am taking leave of him are only making him still more alive, for only the admission of a great loss attest to the true possession of that which is ephemeral. And only the unforgettable dead remain truly alive for us!2

Today, the importance of Verhaeren as an example to younger writers of his epoch, now famous figures of the canon, his stature as ‘maitre’, is, like his poetic legacy, unacknowledged in Britain and other Anglophone countries. Verhaeren is at the moment of writing all but invisible, as if he never existed, an unforeseen casualty of history and yet in his time he was admired and loved with almost religious devotion, not only by Zweig but many others, notably Rilke, who in Paris, sustained himself on Verhaeren’s expressive life-affirming poems, visited him regularly in his St Cloud house.

How is it that a man of such calibre, vision and influence can fall into such devastating obscurity? How can it be that a name once spoken with admiration and awed respect, a name well known to English translators, critics and poetry readers in the first decades of the twentieth century, can now not even raise a glimmer of recognition? Such are the fallacious paths of the historical labyrinth we find ourselves in. Zweig and Verhaeren are irrevocably interlocked, their destinies grafted onto one another. But fame or the absence of it is, in the end, a peripheral matter; it is only the inner creative destiny of each and where it is touched by the influence of the other that counts.

This article was first published in the online magazine The Public Domain Review on 11 December 2013.