Enter At Your Own Risk: The Houses of Jonas Vansteenkiste

In Jonas Vansteenkiste’s (b. 1984, Kortrijk) visual artworks, architecture plays a significant role. He uses sculpture, photography, drawing, installation or video to construct spaces or create situations that are best described as ‘mental environments’. He invites the audience to enter.

Hilde Van Canneyt: ‘The house’ fascinates you both as an architectural and psychological concept. The house as both temptation and trap.

Jonas Vansteenkiste: ‘The house does appear often as a motif in my work because it is a universally recognisable thing, with both a personal and common character. I translate my experience with a certain type of building, house or room into a work. This way, anyone can recall through it their own story or experience. In a best-case scenario, it functions as a trigger. Not every work has to allow for that, but it is a concept that fascinates me.’

Jonas Vansteenkiste

Jonas VansteenkisteFor you, a house can embody multiple meanings: it can be a bunker or a skeleton, or even skin.

‘A house’s first manifestation is often basic but can be deployed as a metaphor for other things and feelings. A house can represent hope. My work Dreamers

is about fantasies and longing. But in Housetraps the home becomes a device of trickery; it is a dream or desire that imprisons you into something deceptive. The old-Germanic word for ‘house’ is derived from the word ‘Hutte’, which means ‘hut’ but also ‘skin’. Etymologically speaking that is the origin of the word. For me, this intuitively made sense: the house as equal to a second skin. The word ‘house’ can be felt as suffocating or claustrophobic. I am investigating this duality in my new work, Soft Houses, featuring leather hides in skin tones, very sculptural, with architectural elements such as windows and doors.’

The Sublimation of the Subtext, sculpture/installation, 2019

The Sublimation of the Subtext, sculpture/installation, 2019The Sublimation of the Subtext is another work you are developing. In it, you integrate text into the work. I couldn’t help but notice that your works are always firmly contextualized by philosophy or works by other artists and writers. Is that necessary?

‘My artistic practice is research-based. I am not someone who spends time in the studio sticking two pieces together to arrive at a skeletal structure. My work is content-driven. I do research, read and write a lot, and ask questions continuously. That is why I sometimes find myself paralyzed and working a lot slower than other artists. But that is the process. People used to tell me: ‘It is so aesthetic’. I am indeed invested in a certain degree of aestheticism, but I think people misrecognize how substantial my process is. Even though, for me, that is a fundamental part. I don’t know if it is always necessary, but as a viewer or interested party, you can engage with the work on a deeper level. That is also how I approach building my website. I try to keep my writing accessible.’

A House is not a Home (housetrap), installation, 2014

A House is not a Home (housetrap), installation, 2014Your titles are substantiated. They are thought through.

‘Calling my works ‘Untitled’ doesn’t suit me. To me, titles are the key to depth. The reflection they invoke is like a building block to me, whether you connect to that as a viewer or not.’

You write down your ideas in notebooks, which you like to describe as cookbooks in which you list ingredients. Over the years, these notebooks have become works in their own right.

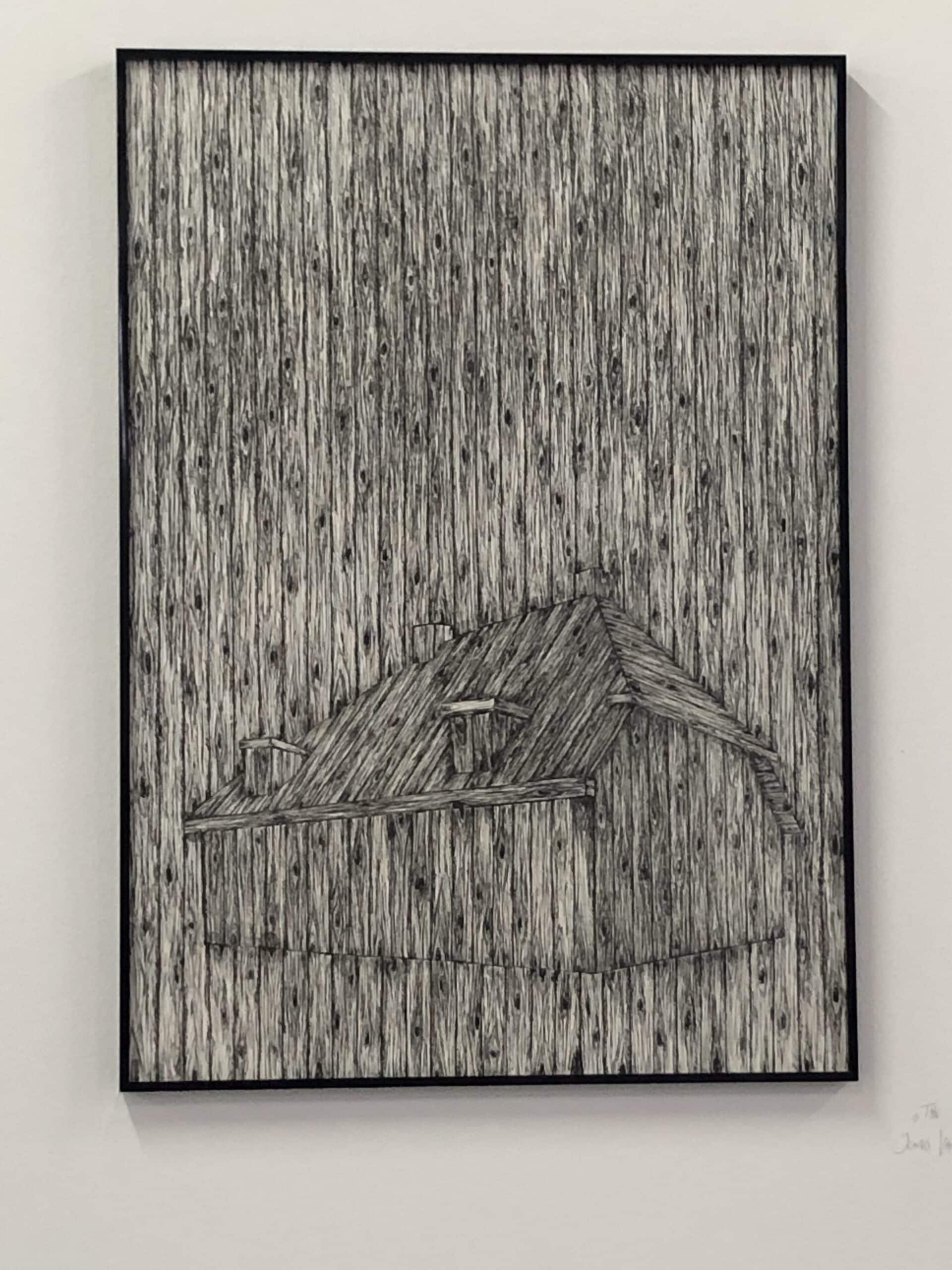

‘When I started, I doubted whether my drawings were able to translate my work well enough. For me, drawing is like thinking, and I wasn’t sure if showing them was always relevant. These last three years some works, like Vanishing Point, in which the pattern of a house dissolves into the pattern of the wood and vice versa, have become based in drawing. Drawings expose more emptiness, doubt, mistakes…these things can make an image work. This has led to several series that are just on paper and will not lead to any spatial manifestation.’

The Vanishing Point #1, drawing, 2017

The Vanishing Point #1, drawing, 2017Is that because you feel like you have exhausted the narrative? Mind you, narrative is not the right word, since you are not a narrator.

‘At first sight, it might come across as a mere aesthetic narrative, but upon a second look, the viewer will notice that it is more than just a pretty picture. I use aestheticism as a method of cajoling. Opinion might be divided on this tactic, some artists might find it disruptive, but if it allows the audience to engage with the content, I think it is a relevant practice.’

You think it is important for the first visible layer to be understandable, I suspect.

‘I believe that recognition or attraction is always key to discussing difficult topics. Any work that operates in this way can touch on many more things, which will lead to increased dialogue.’

In some way, you say that ‘time’ is the crucial element to your practice.

‘Most people think I produce a lot, which is true in some way, but I work on many projects at once. I have ongoing projects, left to develop on my desk because I feel that they need to be left alone – and then suddenly they are finished. If I were to unexpectedly have to finish an exhibition next week, I would not be able to just mash something together and work on it until the last minute. For me, things need time to cultivate. Everything will need to be measured and I want to understand what an image communicates. Some works see five different iterations because I feel that they are not ready to be displayed publicly. That is why often I don’t work towards an exhibition, or promise to deliver on new work because I find that tricky to do. Often the work hasn’t matured enough and is too precarious to show. That is unfair to the viewer if you ask me. And of course, it is also because of me. I have yet to discover whether or not it works.

Most exhibitions develop rapidly, but I believe that will change with time. People are obsessed with showing new work. I believe we need to develop the awareness that artists are not producers. In our current context, I think there is too much emphasis on production and too little on the question of why artworks are made.’

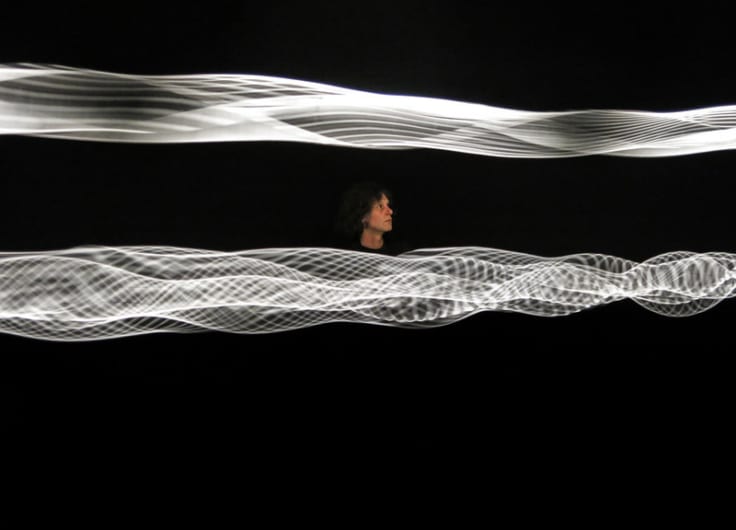

Dreamers, light box, 2018

Dreamers, light box, 2018Your works depart from a basso continuo that builds outward: the personal disappears and you invite audiences to effectively enter into the work and actively engage with it. Everybody will project their own experience of a house onto it.

‘The house never really disappears. It stays present as a sublayer. I am not like the artist Louise Bourgeois, whose personal narratives dominate the work. I do follow that kind of methodology, to an extent, but I am interested in a translation to the universal, opening up the work to interpretation. A mere monologue is not interesting to me. I chose shapes and strip them back to their essence. This I expand to a broader totality that is activating. Of some works, I know how they trigger reactions, not just with me but with the viewer. But whether that is, in fact, the same story, I have no idea.’

Mr House, video installation, sculpture, 2016

Mr House, video installation, sculpture, 2016You also see your videos as independent works.

‘My last two videos were different, but often they are spaces that we cannot reach. Particularly the inaccessible or imaginary space. That is what Transit

is about. Mr House represents a game between belief and a lack thereof, and also a relationship between the narrator and the listener, who is themselves a space of course, but one that uses an entirely different method of storytelling. The main character in Mr House recounts the story of someone breaking into houses to find his own home. In reality, he is looking for his own place but cannot find it. The visuals show a puppet with a head shaped like a house, narrating. In the second part, he becomes the subject of his own story. In reality, you never really see the narrator. What you do get is a sense of tension and truthfulness. I believe the artist is always that; something truthful. Like time in intermediate space. Maybe this says a lot about how I approach things.’

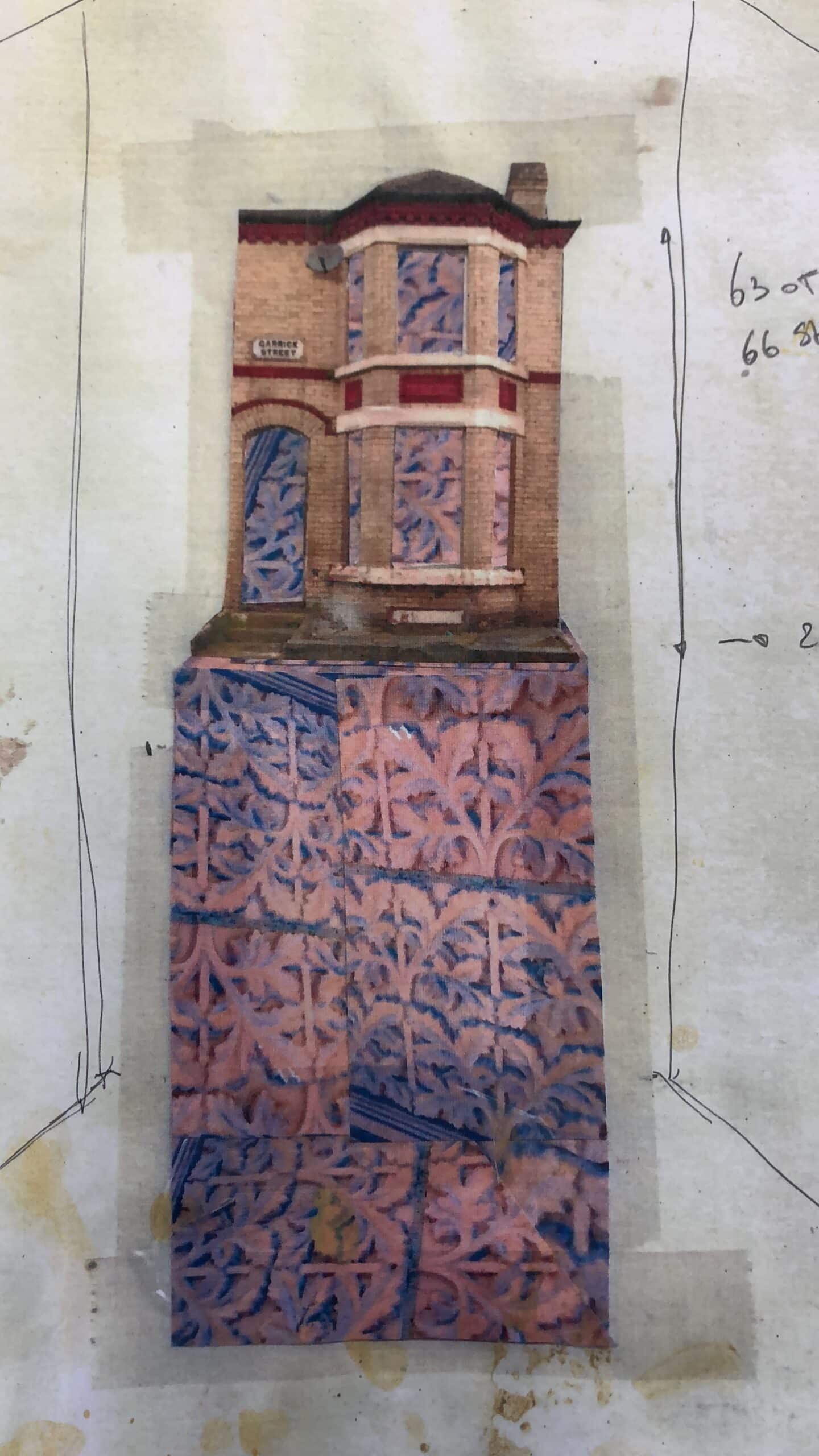

A Pile of Homes, installation, 2014

A Pile of Homes, installation, 2014That ‘the house’ is a recurring subject in your work is telling of the fact that it is an inexhaustible source of inspiration. Once you have researched seemingly everything there is to say about it, you automatically expand into a different subject.

‘It does expand. I also have an extensive interest in Disneyfication and in city planning, as well as the mechanisms that drive it. The experience. My installations always incorporate mechanics. What I have also noticed is how I tend to shy away from politics. However, in my new work Victoria May Thatcher, which is about social housing in Liverpool, I touch upon the ways in which politics control people’s homes, which is a political outlook. Ever since Thatcher, whole neighbourhoods stand unoccupied, because of Liverpool’s protests against her regime. She ended up raising rents, leading to some neighbourhoods ending up as ghost towns. Another work, A Pile of Homes, criticizes the use of cheap materials in social housing. A bunch of bricks are stacked on top of each other, but in fact, this is something valuable deployed as something worthless.’

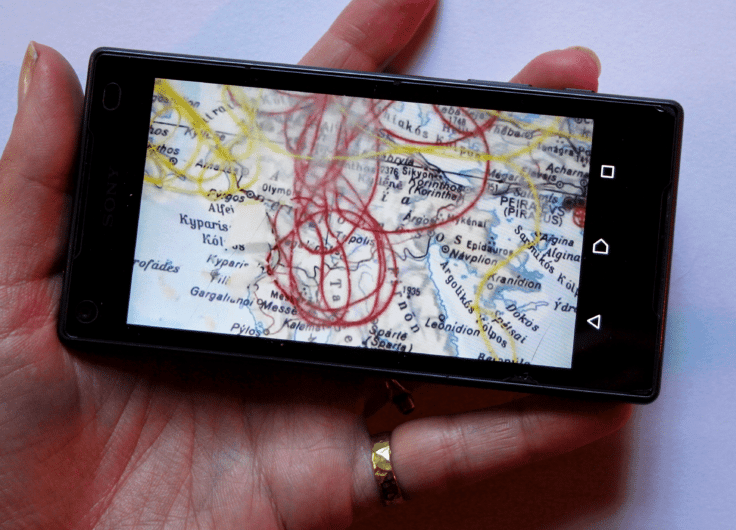

Victoria May Thatcher

Victoria May ThatcherThe last couple of years you have been on many international residencies. What do those add to your arts practice?

‘My Paris residency taught me a lot. I was researching Haussmann and how the ‘organic’ Paris was constructed under Napoleon 3. We say that Paris is the city of romance, but in reality, the city’s streets display a military structure. That period saw a lot of revolutionary protest and Paris was easy to barricade: people would throw all kinds of things onto the streets, between the houses, blocking the army’s access.

Then they thought: ‘We can build sewage and water systems, which would benefit the people.’ In reality, what they were after were broader streets that the army would be better able to keep under control during protests. Paris’ entire look has been conceived by one man. I think that is where you find a kernel of fascism; in façades and their background. The street façades are powerful and uniform, but behind them hides what cannot be seen. It leads to an ambiguous attitude: ‘What do I show and what do I hide?’ That concept interests me greatly.

My second reason for going to Paris was Disneyland. The park was designed for consumerism and entertainment. Yet even there they deploy a similar strategy that visitors are often unaware of. I went to Disneyland every week. One of the works derived from that experience is the video Adventure. It is about liminal space. As a term, it describes zones of transition. It is hard to explain in any concrete way, but there are spaces in the park where you see a waterfall and palm trees on your left, and it seems like you’re in the tropics, and on your right, you see weeping willows as though you are in England. I was interested in showing that moment of transition, because when you are walking around you barely notice it. You accept what is presented to you – even though you know it is fake, it doesn’t preclude you from having a very real experience. This concept hides many strategies. Even after the residency, I kept going over it.’

Fragile Memory II, site-specific installation, Harelbeke, 2015-2018

Fragile Memory II, site-specific installation, Harelbeke, 2015-2018What did you learn from the European Centre for Ceramics in Oisterwijk?

‘That it is the most amazing site for ceramics in Europe. I wanted to work with ceramics for the Liverpool project on disused working-class housing, and I wanted to pay attention to their ornamentation. That duality of arts and crafts was fascinating to me. I ended up mixing those two languages. The plinth is ornamented, and I made a small Victorian house in brick. Through its windows, you can see more ornaments, but everything is closed up, the houses are empty which brings a certain tristesse to the works. The plinth’s cut and porous ornaments reference the content of the work.’

Fractum Domum, palimpsest intervention V, site-specific installation, Berlin, 2019

Fractum Domum, palimpsest intervention V, site-specific installation, Berlin, 2019You stayed in Berlin for a while.

‘I was in Berlin to see Albert Speer’s work, but that turned out to be much harder than I anticipated because people don’t like to talk about it. Luckily, I had made many photographs in the first two weeks and they showed numerous buildings that had been bombarded and dressed in lead. That struck me as a kind of wound, scar tissue, or a remnant of trauma. I am currently experimenting with those images.’

How has your work evolved over the last few years?

‘I am more capable of showing my process and changing up my subjects. I have also grown in my choices of materials. Being able to choose construction against, for example, tactile ornaments. My work has become increasingly layered in its manifestations.’