Etty Hillesum: a Life Interrupted, a Spirit Unperturbed

In 1981, nearly forty years after she was killed in Auschwitz, Dutch Jewish Etty Hillesum found fame overnight after her diary entries were published in Het verstoorde leven (An Interrupted Life). Her diary notes, which she jotted down in occupied Amsterdam, are a testament to strong personal development and display great literary talent. In this article, Philippe Noble, who translated Etty Hillesum’s work into French, tells us why the writings she left behind are still as powerful today as they ever were.

Etty Hillesum in 1939

Etty Hillesum in 1939© Wikipedia

When Etty Hillesum (1914-1943) starts keeping a diary in March 1941, she is still living the almost normal, albeit Jewish, life of someone who had completed studies in law and Slavic languages and had grown up in a very protective Amsterdam environment. However, she is suffering from depression, and keeping a diary is part of her therapy. She does so at the suggestion of her analyst Julius Spier, a German refugee, whom she had recently met.

This meeting would add lustre to about eighteen months of her life, i.e. the period she is writing this diary. Spier, who is 27 years her senior, takes care of her, advises her, becomes her mentor, friend and lover – although physical intimacy is not dominating their relationship. Up until May or June 1942, for the most part, Etty’s diary is an account of this passionate, exciting and mutual love, which changes both her life and her as a person. In this internalised and uncertain written exploration, she is able to find an answer to her menacing surroundings.

Julius Spier

Julius Spier© Wikipedia

Then, life catches up with her. At the start of the systematic deportation of Jews, Etty, who refuses to go into hiding, is pressured to take on administrative duties for the Jewish Council (the intermediary organization established by the Germans as a means to assist during the persecution of Jews). Being a social worker, she voluntarily transfers to Westerbork transit camp, where nearly all deported Dutch Jews pass through. Just a few weeks after her transfer, Spier dies from lung cancer.

The letters – about a hundred in total – that gradually replace the diary from the summer of 1942 onwards, allow us from then on to travel with Etty to Westerbork for short periods of time, interspersed with longer recovery periods in Amsterdam. In June 1943, Etty became a permanent camp internee in Westerbork. To some extent, that was her own personal choice. In September, she is deported to Auschwitz, just a few days after she, in a clandestine letter, had painted a staggering picture of the trains leaving in convoy in the middle of the night. She is killed in Auschwitz in November 1943.

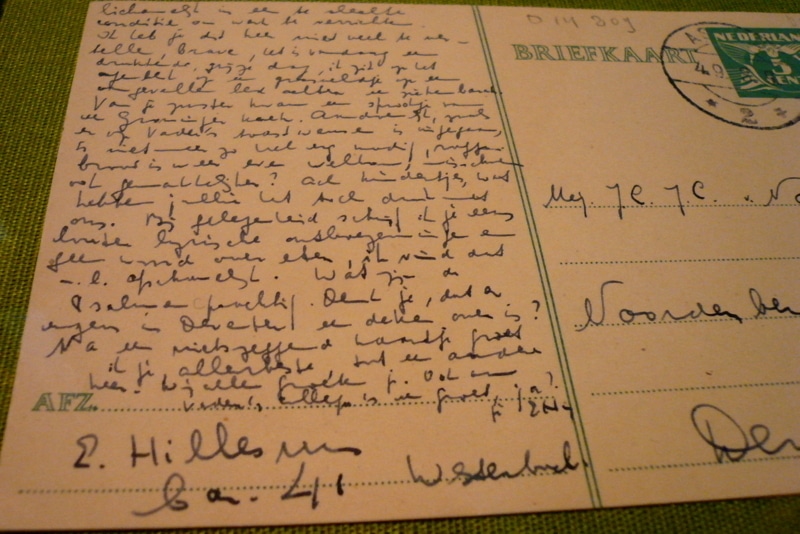

Postcard written by Etty Hillesum, sent from Westerbork transit camp

Postcard written by Etty Hillesum, sent from Westerbork transit camp© gildeamsterdam.nl

Always a different view

Etty Hillesum’s writings are a world of their own, or, better yet, a vast ocean, home to many, at times clearly visible, at other times, somewhat hidden undercurrents. Whoever immerses him-/herself in it, can feel themselves drift along in many different directions. If you jump to conclusions too soon or want to draft a compact synthesis, you are in for a disappointment. We should never forget that Etty wrote primarily for herself, initially for therapeutic purposes, and set out on an internal quest – with a courage that is not to be underestimated, – without a clue where it would take her. Moreover, she was devoid of any urge to find systems and definitely lacked a desire to cover up contradictions in her thinking. That explains the sometimes-contradictory reactions to Etty’s philosophy.

Etty’s writings continuously offer us a different view, and, ideally, a reader should have an eye for each one of these views. This does not mean, however, that all interpretations of her work are equally justified.

Camp Westerbork was a transit camp in the Drenthe province, meant to serve as a refugee camp for Jews who had illegally entered the Netherlands.

Camp Westerbork was a transit camp in the Drenthe province, meant to serve as a refugee camp for Jews who had illegally entered the Netherlands.© Wikipedia

German as a cultural language

Etty’s thoughts about the war, for instance, are never based on political analyses, but can only be understood from her own preoccupation with psychological matters. That is also true when it comes to her understanding of resistance, which for her always equals a moral, inner resistance. Taking this into consideration, every debate concerning Etty’s alleged lack of resilience, the criticism of her supposed “fundamental pacifism”, as though she was like a lamb to the slaughter, actually becomes redundant.

What is significant here, is that she consciously refuses to develop an image of the enemy. She does not want to create a monstrous abstraction of ‘The German’, on which to then project negativity. She rejects hatred. In today’s age of phobias, including islamophobia, she is – and, in my opinion, continues to be – a memorable role model.

That attitude shines through most clearly in Etty’s relationship with the German language and culture. Next to Dutch, i.e. the language she writes in, and in which she hopes to acquire further skills, Etty harbours a special fondness for two other languages: Russian, where she believes part of her identity resides, and German. German is the language of her love affair with Julius Spier, and would later become the language of her relationships with other men; it is the language in which she communicates with the many German Jewish refugees within her circle of friends, and would also become the language she uses on a daily basis with a lot of ‘prominent figures’ in Westerbork. The German language also serves as a vehicle for her innermost quest, through reading, for instance, the works of Carl-Gustav Jung and (even more) Rilke. It is also the language of the translations from world literature she often reads. In short; German, in her opinion, is never ‘the enemy’s language’, but in fact the language of culture par excellence, as well as the language that is connected to the most important event in her life during the years she keeps a diary. An almost tangible symbol of the latter is the fact that Spier’s library is transferred to Etty’s room in the Gabriël Metsu street in Amsterdam: from then on, she is quite literally surrounded by that language and literature and spends all of her days reading.

Etty Hillesum wrote her famous war diary in her Amsterdam house in the Gabriël Metsu street, number 6.

Etty Hillesum wrote her famous war diary in her Amsterdam house in the Gabriël Metsu street, number 6.Defenceless God

Throughout the rich history of the reception of Etty’s writings, she has often been portrayed as a contemporary mystic, especially in Catholic circles. The truth, however, is not as straightforward. Being a non-believer with a Catholic background (if I may describe myself in this oversimplified way), Etty’s religious experience feels simultaneously familiar and mysterious. For starters, I am quite sensitive to her struggle with both the word and the concept ‘God’, which is exemplified by this quote:

‘I find the word “God” so primitive at times; it is only a metaphor after all, an approach to our greatest and most continuous adventure. I am sure that I do not even need the word “God”, which sometimes strikes me as a primitive, primordial sound. A makeshift construction.’ (22 June 1942)

But I am also deeply impressed by the notion she finally conceives in her diary, although I cannot call to mind what exactly lies behind her metaphors:

‘There is a really deep well inside me. And in it dwells God. Sometimes I am there, too. But more often stones and grit block the well, and God is buried beneath. Then He must be dug out again.’ (26 August 1941)

‘I shall try to help You, God, to stop my strength ebbing away, though I cannot vouch for it in advance. But one thing is becoming increasingly clear to me: that You cannot help us, that we must help You to help ourselves. And that is all we can manage these days and also all that really matters: that we safeguard that little piece of You, God, in ourselves.’ (12 July 1942)

We should consider Etty one of the most important religious thinkers of the previous century

Again, I am still not quite sure about the reality of this “God”, but I believe that we should consider Etty – precisely because of this spectacular turn-around of the positions of God and man in relation to one another – one of the most important religious thinkers of the previous century. A defenceless God who lives in our hearts and whom we should protect against the horrors we have unleashed upon the world: that is a concept of God that, in my opinion, could profoundly affect many people, also – and especially – outside of the traditional, well-established churches.

For a long time, I believed that Etty’s notion of God should be approached independently of the scourges of World War II and should be mainly looked upon as a type of spiritual innere Emigration: a quest inside yourself for what you can no longer find in the outside world. But (I think) it is more than that; it is a conception that could also be valid today. For some years now, we have been experiencing a phenomenon, which many people of my generation would not have deemed possible: the return of God. Not in the guise of an ‘inner God’, but in the form of an explicitly ‘outer’ or ‘external’ God, who issues commandments and – particularly – interdictions, curses people and enjoys condemning people to death. And this is not limited to a single religion, but (albeit in various degrees) occurs within all three monotheistic religions. I would love to, as a kind of theoretical experiment for our contemporaries, confront this vengeful God with Etty’s Lord.

Contemporary

The diaries introduce us to a young woman who did not – or hardly – care about the world’s commotion but would rather find a solution for her own internal struggles, and eventually found a way out through spirituality, through a highly personal interpretation of faith.

But let there be no mistake: the diaries are largely about falling in love and feelings of love, about the love for one man, Julius Spier, and also for other men, and even for a woman, once in a while. That aspect of her writings suddenly renders the somewhat ethereal author very down-to-earth, very feminine, very – in a word –human.

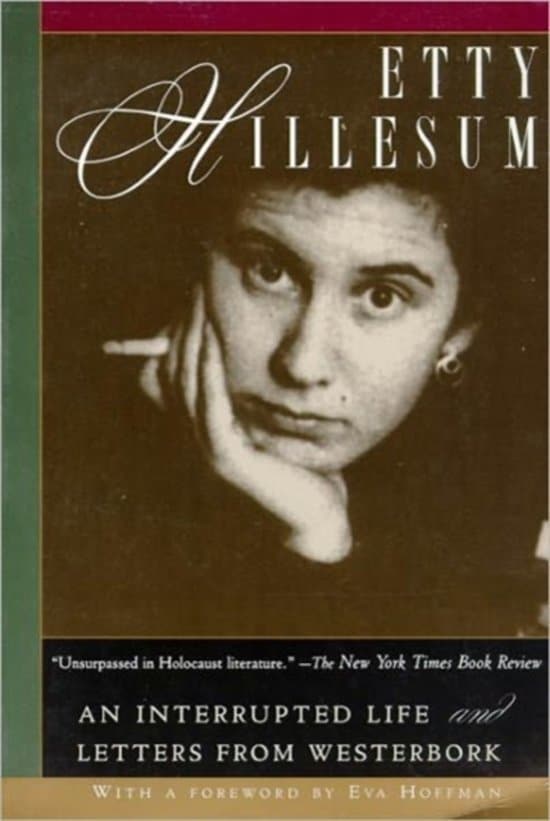

Etty Hillesum

Etty Hillesum© NiOD

To me, all of this makes Etty a very modern, highly contemporary character, and, in the end, I did not approach her as a historical figure as such, but rather as someone whom I could consider an acquaintance, whom I could have come across in the university corridors, if I had not, by complete coincidence, had gone to college in Amsterdam some thirty years later. Of course, this is just an idea, a complete illusion, but it does say something about the fascinating sense of intimacy that the contents of her diaries can evoke.

Even more so than the diaries, the letters unveiled Etty’s remarkable gift of empathy for her fellow human beings to me, as well as her unique skill to bear witness to life. Only then, I felt I heard Etty’s ‘genuine’ voice. Even today, I am convinced that these letters are the smoothest gateway to her work: in the letters, you can read how Etty saw the world, in her diaries you can gradually discover how she, with difficulty, acquired the inner conviction she used as a window on the world.

Concluding words

What is miraculous about Etty’s diaries and letters is the fact that, even after all these years, her voice resounds as loudly and clearly as ever, that we can still recognise – and I would like to add, share – so many of her desires, doubts and moments of despair. The combination of a keen mind, an exceptional susceptibility and sensitivity, especially during one of the most tragic times in our history, is what makes Etty Hillesum’s legacy truly unique. It is highly unlikely that many more of Etty’s letters or diary notes will surface, although there are still scholars out there looking for them. However, what we do have, has not yet revealed all of its meaning, and I am afraid that these turbulent times will often lead us to find solace in this extraordinary source of humanity.