Eugeen Van Mieghem’s Compassionate Sketches of the Tired, Poor and Huddled Masses

Last year, a private collector donated eighteen drawings by the Antwerp artist Eugeen Van Mieghem (1875-1930) to the New-York Historical Society in Manhattan: a generous, but above all a relevant and strategic gesture. Relevant because it confirmed the link that Van Mieghem himself depicted with such power more than a hundred years earlier: the experiences of the thousands and thousands of mostly Jewish migrants who left Antwerp for America. Strategic because the donation was an important step towards making the Antwerp artist known worldwide.

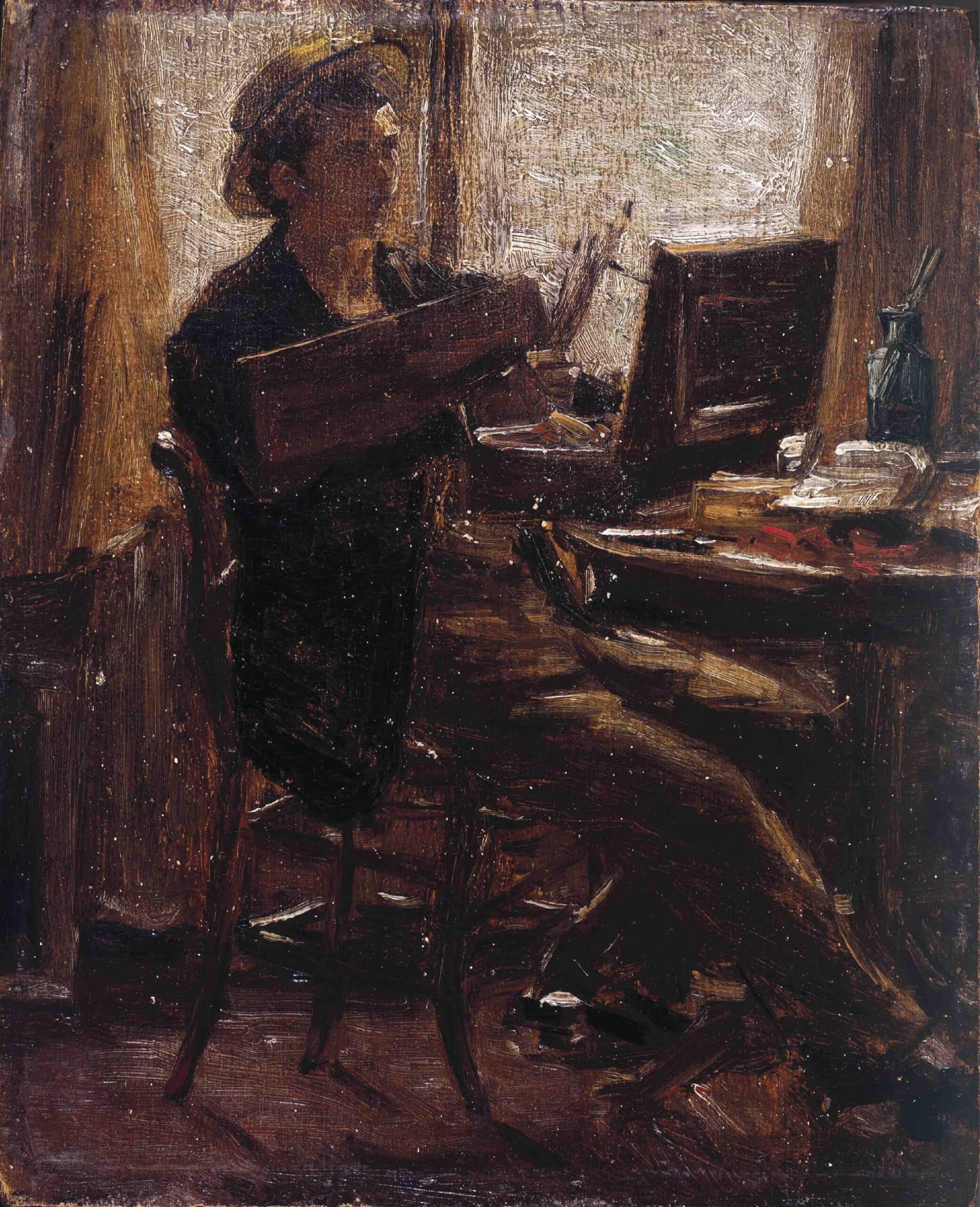

Eugeen Van Mieghem (1875-1930), ca. 1907

Eugeen Van Mieghem (1875-1930), ca. 1907© Eugeen Van Mieghem Museum

Van Mieghem was not a traveller: he rarely left his hometown and his art did not require him to do so. He found abundant subject matter in Antwerp’s harbour, in the streets and in the bars. His focus on the local scenery was in no way an obstacle to his career; today, interest in his work is steadily increasing. In 1993, Antwerp gave him his own museum, and widespread international interest soon followed, with exhibitions in Amsterdam, New York, Berlin, Prague and Dublin, amongst other cities. In May 2024 the Pissarro Museum of Art and History in Pontoise, near Paris, will exhibit a representative selection of Van Mieghem’s work.

Self-portrait, 1894, Eugeen Van Mieghem Museum

Self-portrait, 1894, Eugeen Van Mieghem Museum© Eugeen Van Mieghem Museum

In a career spanning more than 35 years, Van Mieghem turned his hand to almost all of the classical mediums: oil painting, drawing, watercolour and gouache, monotype, line and dry-point etching. But even that multitude of mediums cannot disguise what he was in the first place: a draughtsman. What Van Mieghem did as a painter and graphic artist can be done by many artists. But as a draughtsman, he is completely unique. It was drawing that allowed him to do what he loved most: walk around the city and sketch life right as it was happening: quickly, roughly, and spontaneously.

Authenticity

For Van Mieghem, life was the people: the docker, the bagger, the soldier, the emigrant, the ragamuffin, the king and the emperor, the bourgeois man and woman, and his own wife. His depictions of his subjects were not even remotely objective but always filled with emotion – from compassion to villainous mockery, from respect and tenderness to deep disgust. Form and content were one and the same in Van Mieghem’s work. His unpolished drawing style was perfectly suited to the raw reality he encountered in Antwerp’s working-class neighbourhoods at that time. His entire body of work is convincingly authentic: Eugeen Van Mieghem does not pretend.

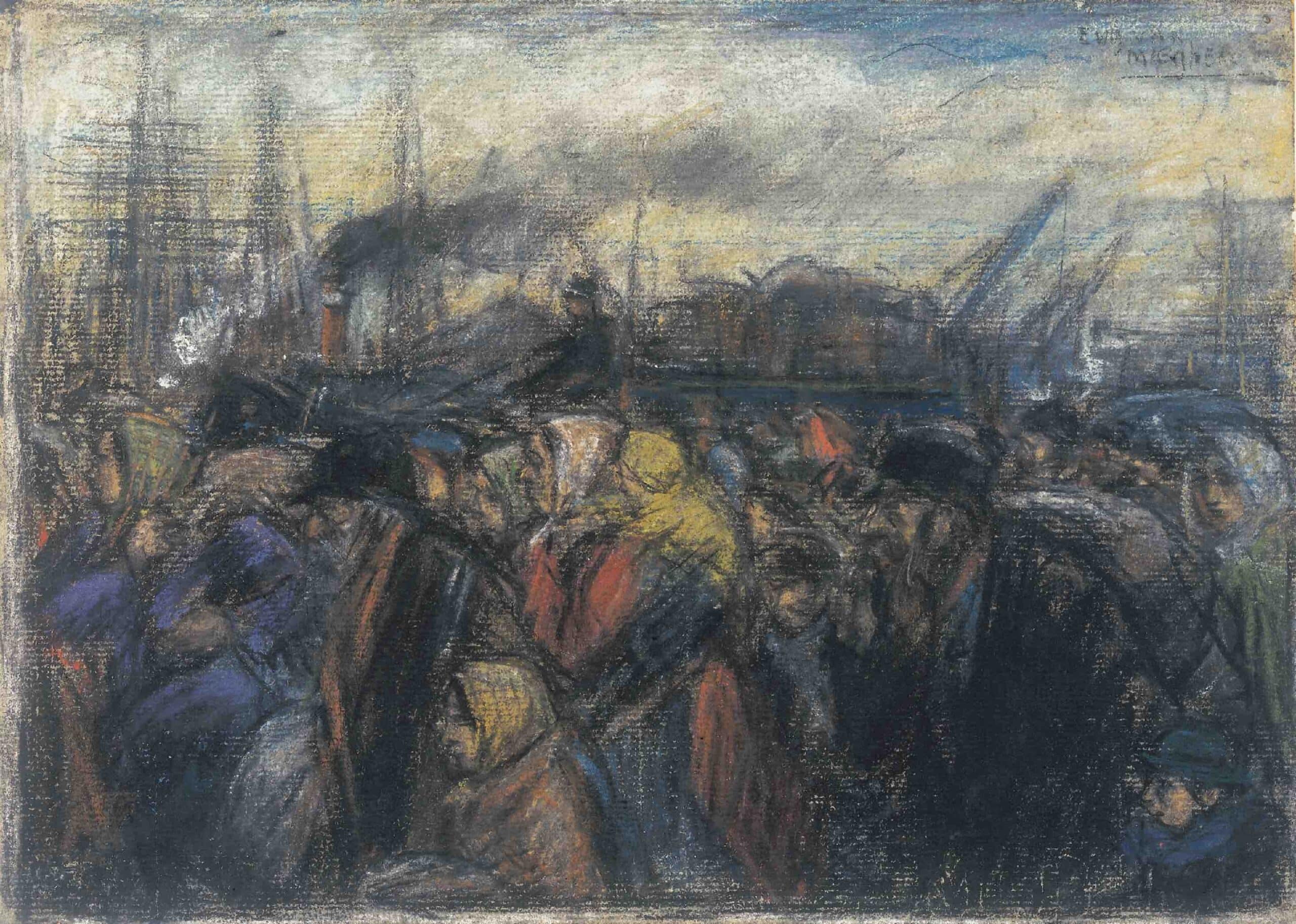

The refugees, 1914, Eugeen Van Mieghem Museum

The refugees, 1914, Eugeen Van Mieghem Museum© Eugeen Van Mieghem Museum

His own origins naturally render his authenticity indisputable. Van Mieghem was a working-class boy who grew up in ‘In het Hert’, the café where his mother was behind the bar. He also worked for a short time in the port and was, therefore, keenly familiar with the surroundings.

The emigrants

From 1873 to 1934, Antwerp was one of the most important ports of emigration in Europe. Many thousands of emigrants, mostly Jews, flocked there to escape the poverty and pogroms in Eastern Europe. The Red Star Line shipping company transported more than two million passengers in total, mostly in third class. For them, going to America was a risky and expensive venture.

Moving stories have been recorded about the medical checks on departure and arrival; in some cases, the family’s best cow had to be sold to pay for the son’s crossing. Once he had arrived, the new American conscientiously put a dollar in an envelope every month for years to settle his debts.

Jewish emigrants departing on the Red Star Line, 1899, private collection

Jewish emigrants departing on the Red Star Line, 1899, private collectionThese were the people that Van Mieghem found in the streets around the harbour, waiting, strolling, or resting on their meagre luggage. As a result, this part of his work, apart from being a high-quality artistic achievement, also serves as a record of social history.

But Van Mieghem’s historical record cannot be considered objective. Empathy, even pity infuses his drawings of the migrants. Though his portrayals can legitimately be seen as technically crude, he is somehow able to depict profound emotions such as resignation, dejection and emptiness in the faces of his characters. In this part of his work, there is not much that can really be called uplifting.

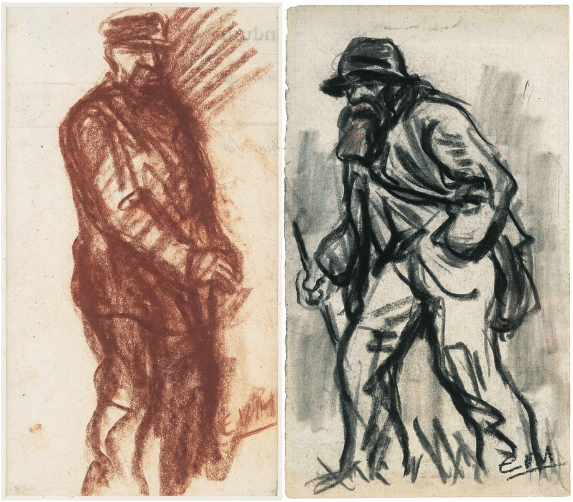

Emigrant with hat, Walking emigrant, ca. 1902, collection New-York Historical Society

Emigrant with hat, Walking emigrant, ca. 1902, collection New-York Historical Society© New-York Historical Society

Yet his attention to the desperate poor and their miserable living conditions was not unique in art at that moment. His war impressions are reminiscent of Käthe Kollwitz’s (1867-1945) portrayals of the madness of war and the despair of mothers who have no bread for their children. In the late 1890s, Van Mieghem became acquainted with the work of Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (1859-1923) and Edvard Munch (1863-1944). Although both of those artists made a deep impression on him, his own place in the artistic spectrum remains unique: no one has dealt with the tragedy of migration as poignantly as he did.

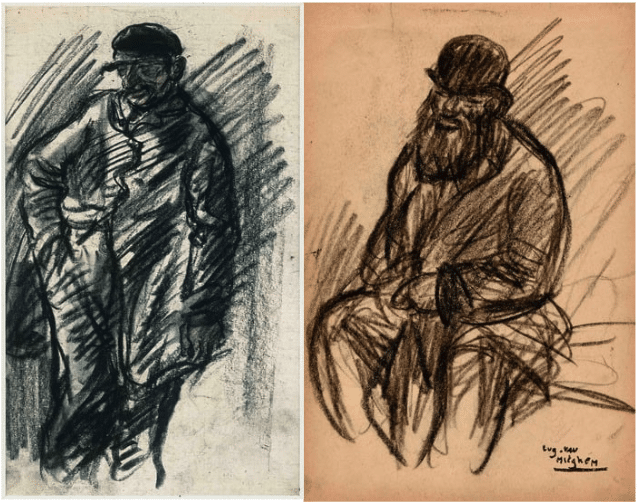

Emigrant on the street, ca. 1902, collection New-York Historical Society / Jewish emigrant with bowler hat, ca. 1904, collection Museum of the Jewish People, Tel Aviv

Emigrant on the street, ca. 1902, collection New-York Historical Society / Jewish emigrant with bowler hat, ca. 1904, collection Museum of the Jewish People, Tel Aviv© New-York Historical Society / Museum of the Jewish People, Tel Aviv

Van Mieghem is certainly repetitive with this theme. The same type of person appears again and again: the tired, listless, impoverished Jew. With so much repetition, certain stereotypes – the noses, beards, hats and caps – are inevitable. But these drawings are nothing like the caricatures the Nazis used. Anyone who wants to see the difference only need to compare Van Mieghem’s drawings of migrants with his depictions of the German emperor and his soldiers, or of the Antwerp bourgeoisie. Van Mieghem drew exactly what he observed and he sympathised with the poverty-stricken people he saw.

The port

The port was not only the economic heart of Antwerp and young Belgium, it was Van Mieghem’s stomping ground: he grew up there, he worked there for a while, he walked through it endlessly and, perhaps most importantly, he knew the people. Anyone who looks at his harbour sketches will see a committed artist at work, whose drawings beckon us to enter a tumultuous era.

Port workers mooring a ship, pastel and charcoal, c. 1912, Antwerp Municipal Print Room

Port workers mooring a ship, pastel and charcoal, c. 1912, Antwerp Municipal Print Room© Antwerp Municipal Print Room

Around 1900, work in the port still depended on heavy physical labour, which is evident even in the titles of Van Mieghem’s drawings from that time: Coal Carriers, Bag Carriers, A Heavy Burden. The dockers he drew were built for hard work: sturdy, sometimes downright bulky fellows who did back-breaking jobs and who inspired him endlessly.

From the late 1860s onwards, women also worked in the port, initially primarily as strike-breakers during the sometimes fierce conflicts between poorly paid workers and the harbour bosses. The presence of these women did not go unnoticed by Van Mieghem, as shown in his many depictions of ‘port women’ and ‘bag makers’ – all common mothers and wives who were forced to work to help keep their families fed.

Evidently, when mothers had to work in the port, children had to make the docks their playground. The Dock Urchins, Port Children and Port Rascals served as the artist’s subjects just as often as the adults. And these poor children had exactly the same sense of resignation and misery on their faces as the Jewish migrants did.

Augustine

Despite his fascination with the poor, there was no subject that Van Mieghem worked on with more dedication than that of his wife, Augustine Pautre (1880-1905). He drew her again and again, in all possible attire and poses. She is the dressed-up girl, the distinguished middle-class lady, the pregnant wife, the loving mother, the nude model, and even the pleasant company of older gentlemen. Each and every drawing shows that Van Mieghem loved her passionately and could not get enough of her. By portraying her endlessly, he may have believed that he could keep her close to himself.

'Augustine sick', black chalk, 1905, private collection

'Augustine sick', black chalk, 1905, private collectionAlas, it was not to be. After the birth of Eugeen junior, Augustine contracted tuberculosis. Van Mieghem’s portraits of a lively, coquettish lady became drawings of a woman with a hollow look, ravaged by disease. She died in 1905, after just three years of marriage, at barely 24 years of age. It was during her long illness that Van Mieghem began the most poignant and moving part of his life’s work, perhaps as a desperate attempt to avert both their fates and cope with his grief. But it was all in vain. Augustine’s death marked the beginning of a dormant period for Van Mieghem: he would not exhibit for five years, and no one would see the drawings he made during Augustine’s illness until they were identified and exhibited in 2019.

A range of emotions is visible in the Pautre drawings. In the few carefree years they spent together, he drew her with tenderness. Later, we see his sorrow and powerlessness in the series entitled “Augustine sick”. And here, too, Van Mieghem’s unique skill is striking. He is, once again, at his best when he quickly and spontaneously gets his subject down on paper. Adding more details later does not necessarily improve his sketches.

‘Paw’

Van Mieghem’s drawing style remained remarkably consistent through the years. One of his strengths was that, even in the fastest sketch, he knew exactly where the focus had to be. There – within the focal point – he worked a bit more precisely, and this area is always darker while everything outside of his focus was done with lighter strokes and swipes. Van Mieghem invariably painted and drew the essence, leaving the viewer to fill in what is missing. Even his detailed drawings are quite sketch-like. He was clearly more concerned with creating atmosphere and suggestion than capturing a precise representation of his subjects.

Jewish emigrants on the Antwerp Groenplaats, 1899, private collection

Jewish emigrants on the Antwerp Groenplaats, 1899, private collectionVan Mieghem was noticeably influenced by some of the great names of modernism, such as Steinlen, Munch and Toulouse-Lautrec, but that did not prevent him from quickly finding his own powerful and recognizable style. In artist’s jargon, a powerful hand like his is called a ‘paw’. And truly, Van Mieghem’s ‘paw’ is so recognisable that we generally do not need his signature to identify his work. The drawings that are now included in the permanent collection of the New-York Historical Society illustrate this clearly.

Website Eugeen Van Mieghem Museum