Eva Spierenburg’s Works of Art Infect Each Other

Eva Spierenburg (b. 1987) began to tire of the traditional canvas: yet another rectangle on the wall. It’s no surprise that the Dutch artist, trained as a painter, began to explore more spatial media such as sculptures, installations and video. Nevertheless, recently, after a considerable detour, she has returned to the flat surface.

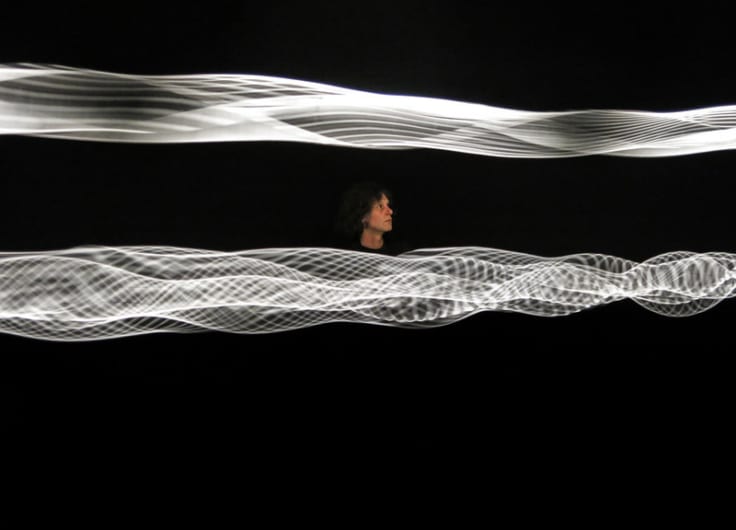

Disappearance in slow motion, 2020, installation, Centraal Museum, Utrecht

Disappearance in slow motion, 2020, installation, Centraal Museum, Utrecht© Eva Spierenburg

Eva Spierenburg originally trained as a painter at Utrecht School of the Arts (HKU). Her paintings at the time had a mythological slant, populated by figures whose anatomy was deliberately off-beat. Gradually paintings began to make her feel claustrophobic: yet another rectangle on a white wall. She describes her early attempts to introduce spatial elements as half-hearted. She also grew tired of figuration: she noticed that in painting people, she was inviting the viewer to pay attention to things she didn’t see as relevant herself. Does this figure properly resemble a person? Is this a man or a woman? Is that person beautiful? Her focus – even then – was not at all on such anecdotal questions.

Painting photos

© Eva Spierenburg

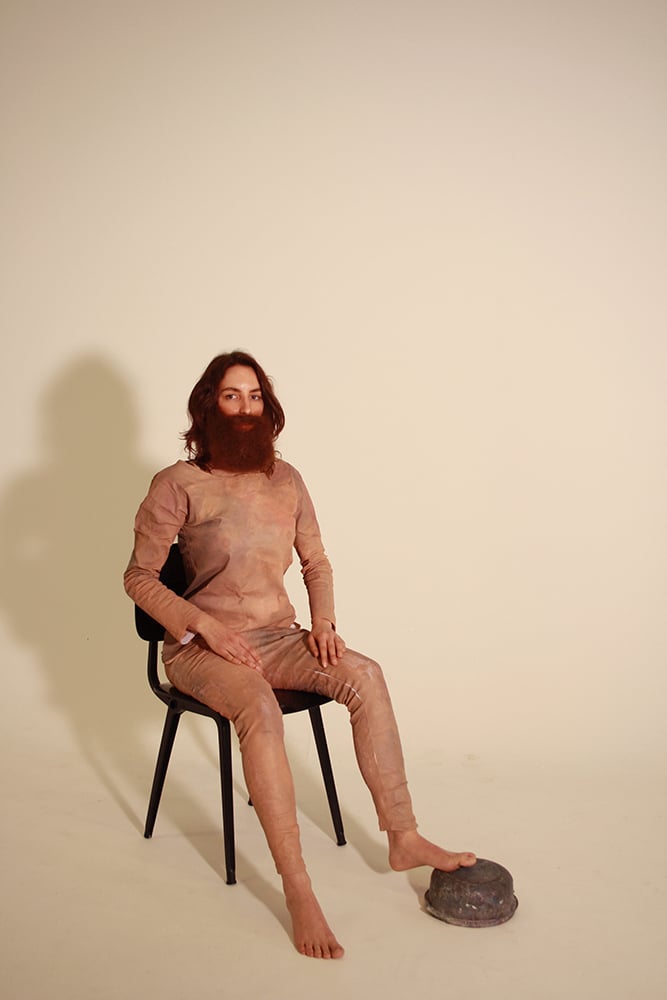

An important first step towards her later multimedia practice was the work He is actually me (2014-2015), consisting of a series of painted photos and a video. The starting point was the male figures which continually popped up in her paintings: were they a kind of alter ego? She made a beard out of her own hair and a kind of naked costume and had her photo taken as these male figures, then painted over the photos. This did not result in truly conclusive answers to her questions, but she’s not really that kind of artist anyway. It was more about the different things she discovered along the way, not least the fact that cross-pollination between media and the performance-component brought interesting leads for new work.

He is actually me, 2014/15, videostill

He is actually me, 2014/15, videostill© Eva Spierenburg

During her two-year residence at the renowned Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten (Amsterdam), Spierenburg continued to explore her new media; not one by one, but more or less simultaneously. The fact that she was interested in performance but preferred not to do it live, for instance, led her to work with video. She also began to make spatial work, which she often combined with other objects and videos to form installations. The position of the separate objects in relation to each other turned out to be of great importance in this respect, as in proximity to one another they could ‘infect’ each other – her own choice of word – with their ambience and meaning.

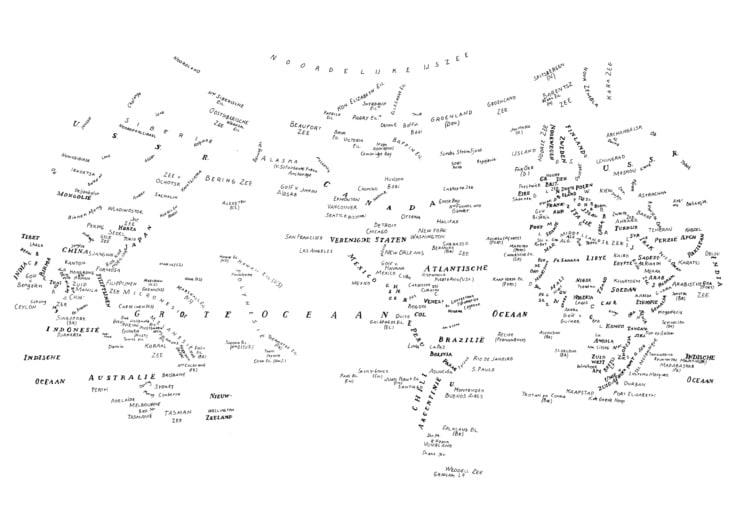

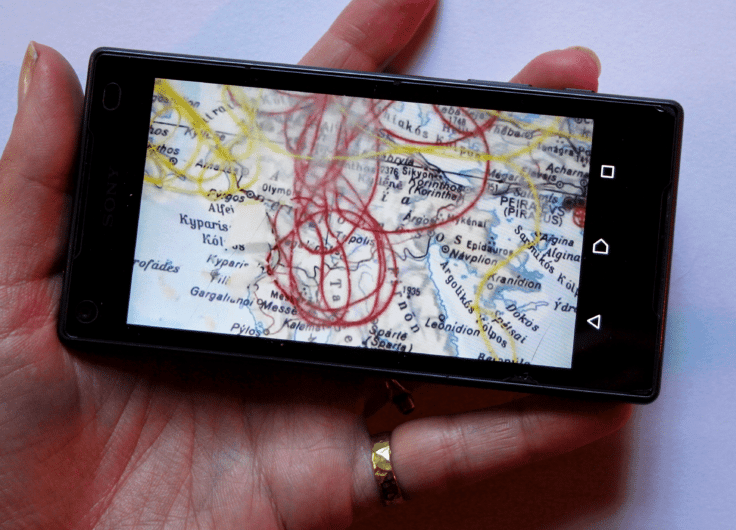

The general human questions in her work began to revolve around a clear, powerful theme: the body. On the one hand that is the flesh that bears your spirit and personality, and on the other hand a kind of instrument for making contact with the world around you. Human figures made way for apparently unconnected body parts such as arms and hands, or their (former) presence was suggested, for instance with a skirt, which looks like it has been left behind.

Tactile skins

Disappearance in slow motion, 2020, installation, Centraal Museum, Utrecht

Disappearance in slow motion, 2020, installation, Centraal Museum, Utrecht© Jan-Kees Steenman

Based on those ‘runaway’ limbs and the often subdued, sometimes sickly colours, it is very tempting to connect Spierenburg’s artwork with physical decline. In her view, however, that is an overly restrictive interpretation: her focus is sensory experiences, also in relation to an object or another person. Illness may be part of that theme, but so is the resilience of the body, for instance in continuing to function. She sees the separate arms and hands in her work not as amputations or the consequence of violence, but simply as a fragment of the entire body. In that sense such an arm ‘simply’ stands for an entire person. In performances such a limb can even function as an extension of the body.

Stillness and the things that were swallowed by the earth, 2020

Stillness and the things that were swallowed by the earth, 2020© Eva Spierenburg

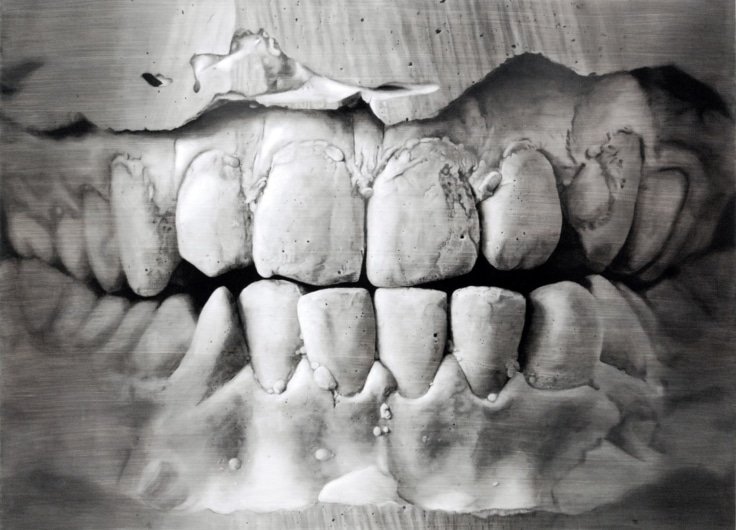

A remarkable similarity between the works in all those different media is the attractively tactile appearance; the role of the skin, you might say, in painting and sculpture, as well as in relation to the body. Spierenburg has a preference for irregular surfaces, folds and materials that leave viewers guessing as to whether they are natural or synthetic. Even a video like Three stages of being red (2018) has something very physical, although it plays out on a smooth screen. Initially a mysterious object, somewhere between a cushion and a stone, is stroked by a hand and eventually broken by two knees. The physical appearance is so totally different in the two moments – it makes you want to feel the object to get an answer as to what you’re dealing with.

Stage at the ready

Those differences and similarities between her works were clearly visible in her first solo exhibition in a museum, Disappearance in slow motion, at the Centraal Museum in Utrecht (12 October 2019 to 12 January 2020), In which she combined different sculptures and videos in one installation; not firmly anchored, but in what appeared to be a loose constellation. The objects varied from a kind of large stone to a silhouette, consisting of a steel frame with a thin skin of cotton and latex. In part due to the large folded curtain in the middle of the room, the performance was strongly reminiscent of a stage setting full of props, as well as the dressing room behind it – especially given the coat-stand-like objects combined with items such as a skirt and gloves with fingernails.

The entire exhibition appeared ingenious while also being spontaneous and varied. For the first time, in preparing for this exhibition Spierenburg worked with a scale model to gain a clear overview of the configuration for herself, also inviting performer Sophia Dinkel along to bring the piece to life – sometimes after visitors had been forewarned and sometimes unannounced. She interacted with the spatial objects, exploring their surfaces, sometimes wearing latex gloves or with an extra arm in her hands. And in doing so she also changed the configuration, causing new infections. She made a calm but playfully exploratory impression, as if attempting to map out the world around her (anew?). The exhibition, in part thanks to Dinkel’s performances, seemed as much to resemble an abandoned stage as one ready for a performance. That’s a form of resilience too.

Installations on the wall

Eva Spierenburg

Eva Spierenburg© Jan-Kees Steenman

Recently painting has begun to beckon again. Spierenburg wondered whether she could combine what she had learnt and discovered over the last few years with the medium in which she was trained. For instance could she translate the spatial aspect of her installations and sculptures into something that could simply hang on the wall? The quest resulted in the series Hidden Remains, recently on show during her solo-exhibition Holding a fish to avoid sinking at the Cinnnamon gallery in Rotterdam. The flat, straight canvases made way for often whimsical surfaces, the contours of which were derived from the imitation of objects such as a stone or a hole in a rock. The traditional (cotton) canvas largely made way for material such as acrylic resin, plaster and wax.

Hidden remains (curtain)

Hidden remains (curtain)© Eva Spierenburg

On or beneath that skin you find the hidden remains that give the series its title. Items such as dried avocado skin or a used shoe sole lend the paintings a layered, adventurous feel. Their unusual shapes and materials are in that sense a logical interpretation of Spierenburg’s theme of humans trying to understand the world. More than sculptures, these new works of art are a kind of installation on the wall, full of elements that infect one another.

A speck of dust from Disappearance in slow motion reappears in Hidden Remains (Curtain); a pleasant sign of a certain continuity between Spierenburg’s various media and approaches. But the greatest similarity is that these new works of art also put their skin fully on show: skin which may or may not be organic, but which always appears mysterious and attractive.