Everything Feels Uneasy About This Exhibition on Looted Art

The Mauritshuis in The Hague is displaying art objects that were once stolen by French troops, colonists or Nazis, confronting you with their past and future. Here, the question is not so much about what is present but more about who isn’t.

Baby rattles and bracelets, brooches and cutlery: the dozens of silver objects that shine in a display case in the exhibition Loot – 10 stories evoke a world of associations. The Polish philosopher Krzysztof Pomian would call them semiophores: objects that acquire meaning as soon as they are withdrawn from everyday life because they refer to the invisible, to the unknown on the other side of reality. They have lost their use value, but have gained another value in return – they have become ‘meaning’.

In which baby’s hand did the rattle rattle? On whose wrist was the bracelet placed? Who held the knives and forks, at which dinner, and who else was at the table during that dinner? Every piece of silver on display catapults us to a reality that has forever disappeared and to people for whom it has, in almost every case, become impossible to give a name and a face.

The items represent only a small selection of a much larger collection of silver objects looted from Berlin Jews and now at the Stadtmuseum in Berlin.

The Stadtmuseum in Berlin, together with several other Berlin museums, is a partner in the exhibition Loot – 10 stories, which can be seen at the Mauritshuis in The Hague until 7 January 2024. The story about the ‘Jewish silver’ is one of ten stories surrounded by old paintings and ethnographic objects. They form the basis of this exhibition – which is also an experience – with the Mauritshuis at the centre. After all, the museum itself has a direct connection with looted art from three periods: the Napoleonic era, the colonial period and the Second World War. Every period is represented at the exhibition.

French troops, colonists and Nazis

French troops looted Stadtholder William V’s painting collection in 1795, and Napoleon also went on a looting raid in many countries – the stolen art was added to the collection of the current Louvre. Most of the collection looted from The Hague was returned in 1815, but some is still in French museums.

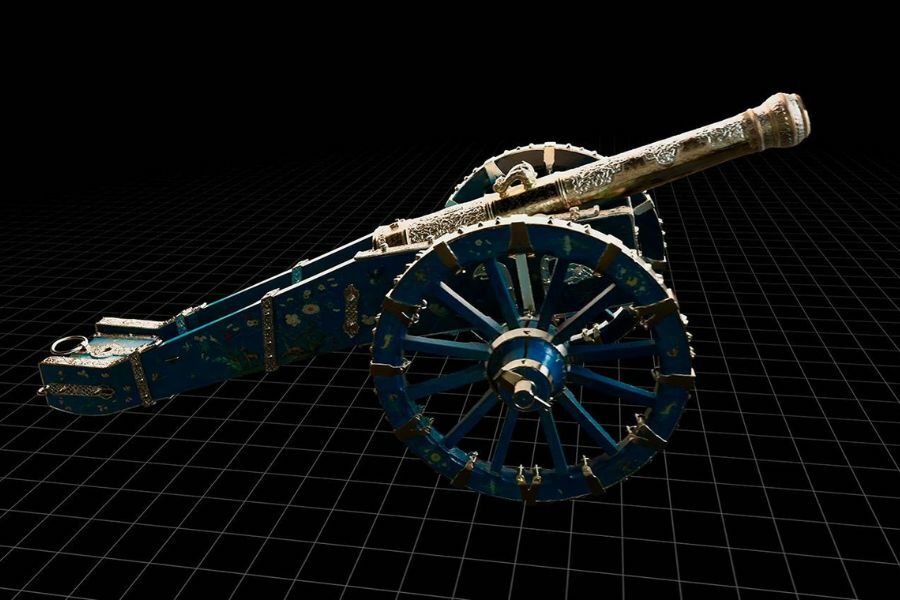

A few years later, between 1822 and 1875, the Mauritshuis housed thousands of objects that belonged to the Royal Cabinet of Rarities. Some of them had been stolen from the colonies, such as the Cannon of Kandy (Sri Lanka). The cannon is still physically at the Rijksmuseum, but has now become a loan: together with a number of other objects, it was recently returned to Sri Lanka.

Finally, the Mauritshuis manages approximately 25 paintings that come from the NK collection, named after the Stichting Nederlands Kunstbezit (Netherlands Art Property Foundation), founded in 1945. That collection consists of cultural objects that were stolen from the Netherlands by the Nazis or forcibly sold to them. After the war, they were returned to the Netherlands with the intention of giving them back to their rightful – usually Jewish – owners.

Jongsma + O’Neill, digital 3D model of Cannon of Kandy, 2023

Jongsma + O’Neill, digital 3D model of Cannon of Kandy, 2023© Mauritshuis Collection

But the original owner of some 3,275 paintings, drawings, carpets, furniture and other objects is still unknown. The Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands (Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed) recently restarted research into its origin. Thanks to digital research techniques, and because more and more archives have made their documents searchable online, the provenance of objects can sometimes still be traced. Through painstaking research, which often takes years, objects can still be reunited with the original owners, their children or grandchildren.

The renewed provenance investigation came about after the Striving for Justice report was published in 2020, in which the Dutch restitution policy was critically examined.

Pressure cooker

How do you convey those often complex stories about looted art, provenance and provenance research to a wide audience? How do you return stolen art to its rightful owners? What does that mean for your museum? These were the questions that the Mauritshuis wanted to address in this exhibition.

A stimulating approach was chosen for this exhibition. Instead of letting the permanent curators tell the stories about looted art, the museum invited two creative leads and guest curators to provide the framing and storytelling of ten case studies: the stories of the past and perspectives on the future of the objects on display.

Through videos and three virtual reality experiences, as a visitor, you are immediately confronted with a number of stolen objects; QR codes on text panels provide a link to background information. And thus you end up in a pressure cooker in which you experience the stories of Cows Reflected in the Water by Paulus Potter; The Marriage of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg, to Louise of Orange in 1646 by Jan Mijtens; Jewish silver; a Self-Portrait by Rembrandt; the quadriga on the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin; a French commode; a Surinamese staff; the Benin Bronzes and a dagger from Bali.

Paulus Potter, Cows Reflected in the Water, 1648

Paulus Potter, Cows Reflected in the Water, 1648© Mauritshuis Collection

And the Cannon of Kandy from Sri Lanka, which has not been set up ‘in real life’ but of which a digital 3D model can be seen. This immediately raises the question: what is the responsibility of museums when showing looted art? How can you display items after they have been returned to their rightful owner? Is that appropriate, or is it inappropriate appropriation? And can these objects be replaced by a replica? Can an object in 3D still be called a museum object?

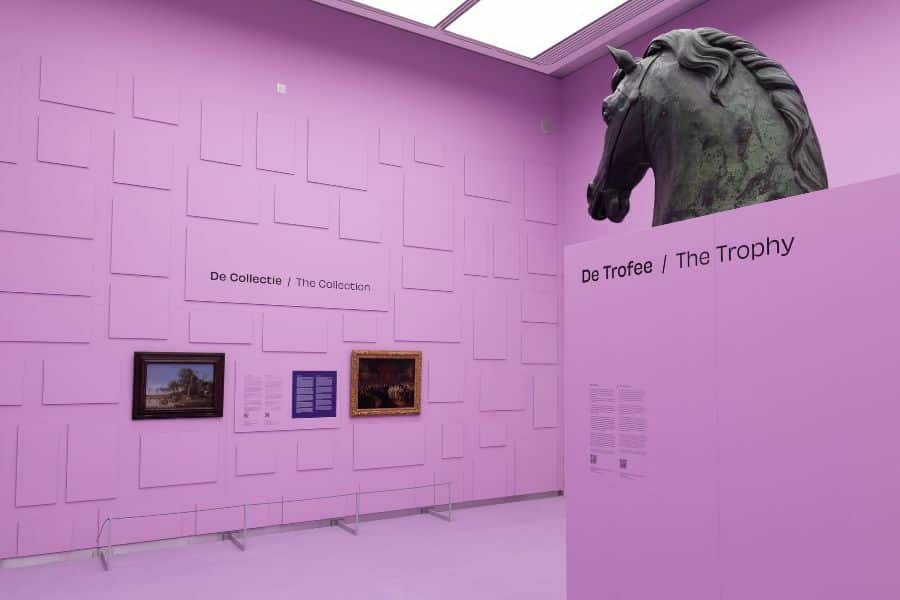

The exhibition at the Mauritshuis makes things even more uncomfortable. First of all, there is the light-purple room, which evades any association with the familiar Mauritshuis museum galleries and looks more like a sci-fi laboratory. This impression is further reinforced by visitors wearing VR glasses while walking through spaces invisible to us or holding on tightly to a balustrade to avoid plunging into the depths from the virtual Brandenburg Gate.

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait, 1669

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait, 1669© Mauritshuis Collection

What also raises eyebrows is that different types of ‘looting’ from different periods are presented equally. For me, who has been intensively involved with restitution and Nazi-looted art, it is an alienating experience that this exhibition lacks hierarchy – and that the story about the art stolen from Jews is ‘just’ one of the stories. For me, who has worked with and for museum curators for years and who loves the time capsule that is the Mauritshuis, it is awkward that in an exhibition about a subject that is so essential, the creative leads and guest curators are so much in the spotlight (the provenance research and the gallery and in-depth texts were, however, provided by the scientifically trained curators of the Mauritshuis).

At the same time, I feel uneasy about my own unease. And while I visit the exhibition, whose structure is so foreign to me, I notice that my perspective slowly changes, that I slowly leave my comfort zone and start to look at things differently. It is precisely because of that unease that I begin to carefully explore the stories unknown to me.

© Mauritshuis

And then there’s also something else that feels uncomfortable. The cold, almost laboratory-like space is in stark contrast to the sometimes emotional stories that are being told. Like the story about the Surinamese wooden staff with a female figure, about which the poet Onias Landveld speaks in a video. His Ndyuka family has strong ties to the area from which the staff was stolen. “The staff means the world to me,” he says, as he watches the female figure being removed from a climate-controlled display case and placed on tissue paper. “I found you all the way here,” he tells her. “This is a part of my history that we didn’t know existed.” It seems, he says, “as if they are putting me and my culture on display, as if I were extinct.” And when asked what he would like to do with it: “Wrap it up and give it to me. I will take it back and find a place.”

The cold, almost laboratory-like space is in stark contrast to the sometimes emotional stories that are being told

Landveld thus touches on another awkward element of this exhibition, and that is its title. Because even though those rattles, the Rembrandt and the staff with the female figure are indeed among objects that have been stolen, they represent much bigger stories: those of the original owners whose lives were once connected to the semiophores. This exhibition is not just about what is present here, but mostly about who isn’t.

“People slip into art and are lost,” Edmund de Waal so aptly wrote in his Letters to Camondo. This exhibition attempts to get a glimpse of those people. Some can still be reunited with the treasured objects of their ancestors. But others will remain lost forever.

The exhibition ‘Loot – 10 stories’ runs through 7 January 2024 at the Mauritshuis in The Hague.