Famines Are Part of Our Living Past

The impending famine caused by the war in Ukraine recalls previous famines: in Ireland, in Ukraine itself, but also in the Low Countries. Famines are part of our living and shared European past, writes Dutch historian Lotte Jensen. They are still interwoven into all facets of society.

As the war in Ukraine continues, the likelihood of famine increases. Russia and Ukraine account for 30 percent of the world’s grain production. As exports are hindered, African countries are particularly at risk, as they rely heavily on imports from Ukraine. The country itself is also facing serious food shortages due to the ongoing fighting.

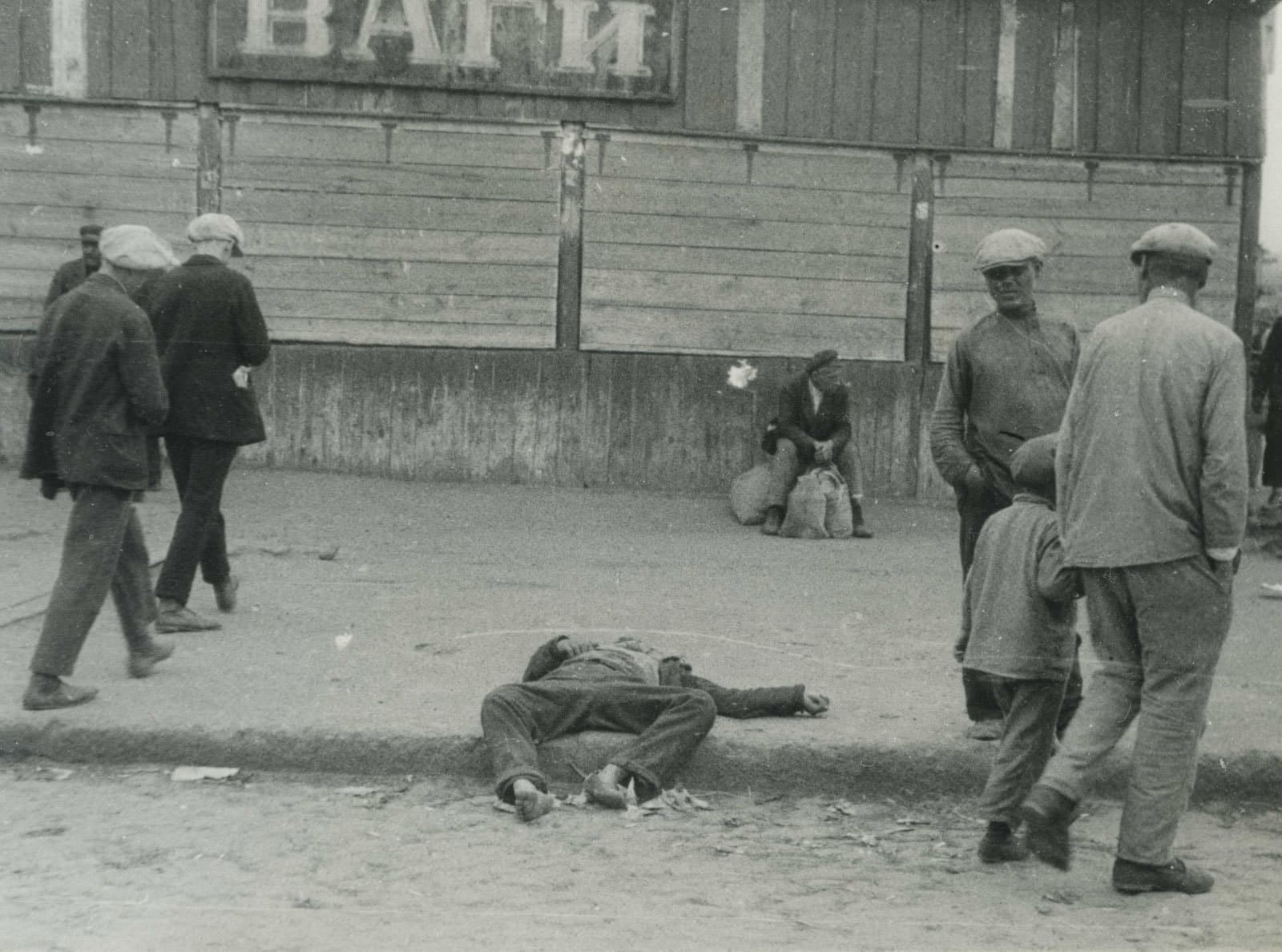

Current events evoke memories of an earlier famine: the Holodomor (1932-1933). Millions of Ukrainians died back then as a result of Stalin’s repressive agricultural policies. This historic famine was kept quiet for a long time, but since Ukraine’s independence, it has served as an important benchmark in national history. Today, the memory of this national trauma strengthens Ukrainians in the struggle against Russia.

The body of a man who died of hunger in the streets of Kharkiv, 1932

The body of a man who died of hunger in the streets of Kharkiv, 1932© Diözesanarchiv Wien/ BA Innitzer / Wikimedia Commons

Famines are part of Europe’s ‘living past’. They may not be tangible or visible, but they are still interwoven into all facets of society. The shared past can be both a source of conflict and inspiration, as the famine in Ukraine illustrates once again. They can split communities, but also bring them closer together. The Heritages of Hunger consortium, co-led by Marguérite Corporaal and Ingrid Zwarte, explores the ways in which European famines of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (including the Ukrainian famine) still live on in societies through a variety of media and institutions, such as films, textbooks, museums, newspapers, and monuments.

Although the memory of famines usually takes place within national frameworks, it is explicitly intended to provide an international comparative perspective as well. Famines are not only living but also shared pasts and can also make connecting lines in European history visible.

Take, for example, the Irish famine that occurred in 1845-1849, which is also known as Great Famine. A fungus, the Phytophthora infestans, caused widespread devastation of potato crops, which caused the majority of crops to fail. In Ireland, over a million people died from lack of food. Although this famine is remembered mainly within Irish circles – there are now bookcases full of writings about this national trauma that triggered mass emigration to America and Canada in particular – it concerned a European disaster. Many other countries were also affected, including the Netherlands and Belgium.

A food riot during the famine in Ireland

A food riot during the famine in Ireland© The British Library / Wikimedia Commons

As in Ireland, the famine left numerous traces in Flemish and Dutch literature. Well-known poets wrote moving poems and songs in which they outlined the dramatic consequences of famine. Take, for example, “The potato plague of 1845, remembered” by the Flemish poet Maria van Ackere-Dolaeghe (1803-1884). She described the suffering of countless families and explicitly placed the catastrophe in a European perspective:

De velden treuren als het graf;

Alom zijn sporen van ’t vernielen

Gedrukt. Geen hoop zendt de Almacht af.

Europa schrikt. Voor ’t altaar knielen

De volken, duizlig van ’t geween.

Maar daalt verzachting? neen, o neen!

De plant zoo, zegenrijk voordezen,

Doet voor het zwaard des hongers vreezen.

The fields grieve like the grave;

Everywhere are traces of destruction

Pressed everywhere. No hope sends the Almighty.

Europe trembles. Before the altar kneel

The peoples, dizzy with weeping.

But does it ease? No, oh no!

The plant thus, blessed, Makes one fear the sword of hunger.

In the Netherlands, writers such as Nicolaas Beets and Anna Barbara van Meerten-Schilperoort supported the needy by pointing out the importance of charity. Beets wrote a song entitled ‘Kerstavond. Troost der armen’ (Christmas Eve. Comfort of the poor), which was set to music in 1872 and used in schools. Thus, the memory of this dark period was passed down to new generations.

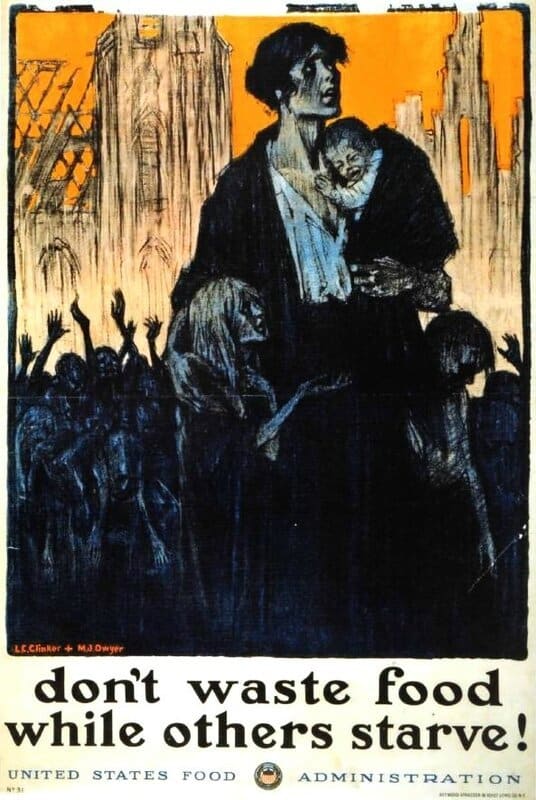

Food waster poster, 1917, The United States

Food waster poster, 1917, The United StatesMarguérite Corporaal’s research shows that the Irish famine led to European solidarity. The Dutch Catholic community collected large sums of money for the needy in Ireland. Within a month, the Dutch branch of the Catholic Society of Saint Vincent de Paul managed to collect the impressive sum of 32,681 guilders (312,177 euros) for the hungry in Ireland. The newspaper De Tijd (May 15, 1847) wrote that the Netherlands, as always, showed its charitable side, even though fellow citizens were actually in need of help themselves. The Netherlands did not want to remain an ‘indifferent spectator’ to ‘the heavenly concert that humanity and Christian love were singing in the whole civilized world for the needs of Ireland’.

In light of current developments, past European famines, such as the famine of 1845-1849 and the Holodomor, are seen in a new light. The realization that Europe has a shared history of famine makes us understand the current situation in Ukraine is closer than we thought. Famines of the past and present are part of the shared and living European past.