‘Farmers’ versus ‘Snobs’. The Social Fault Lines Between Club Brugge and Cercle Brugge

After a local match between Club Brugge (the “blue-blacks” or the “Farmers”) and Cercle Brugge (the “green-blacks” or the “Snobs”), a player from the winning team plants the flag with his own colours in the middle of the pitch at Jan Breydel Stadium, which has been the home of both teams since 1975. The fierce rivalry between Club and Cercle that dates back to the end of the 19th century has much to do with the social divisions at that time. The two teams are, in fact, more closely connected than they might seem at first glance.

As in other cities, both English expatriates and the clergy played a leading role in the introduction of football to Bruges. An English community of retired soldiers, lower nobility, former colonials and industrialists was established in Bruges after the Battle of Waterloo. Many Britons chose the city as a base for business activities related to the mechanization of the linen industry in the 19th century.

Guido Gezelle (1830-1899)

Guido Gezelle (1830-1899)© Letterenhuis, Antwerpen

The presence of the English community gave rise to a sort of Anglophilia that is typical in Bruges. The children of the well-to-do who settled there went to study in England, monks founded houses in Britain and diocesan priests went on ‘English Missions’. In Bruges, typical English-style colleges and an English seminary opened their doors while English people enrolled their children in existing Belgian schools. The presence of the English provided a stimulus for the economic, social and cultural life of the city.

Educational projects followed an English model and attention was paid to English sports. Clergymen played a pioneering role in this context. The Benedictine Gérard van Caloen (1853-1932) and the priest, teacher and poet Guido Gezelle (1830-1899) were very taken with the English ideal of the “muscular Christian,” a movement that emphasised the importance of ethics, health and masculinity through sport, amongst other things. Sports such as rugby, gymnastics, cricket and football were encouraged in secondary schools established in the Walloon Maredsous by Van Caloen, and in Roeselare and Bruges by Gezelle. Soon, the same push for sport in education was introduced by the local Xaverian Brothers who, from 1861, had begun to establish special departments for their many English and German students.

In the meantime, football games had become a twice-weekly event at the Royal Athenaeum of Bruges (part of the national education system organised by the Belgian government). There were competitions between the pupils of the Athenaeum and the English College as well as a weekly match against former pupils of the Xaverius Institute (or the “Frères”), a school founded by the Xaverian Brothers. Only former students could be involved in these competitions, however, because political wounds left by the so-called school struggle made any competition with current Frères’ students impossible.

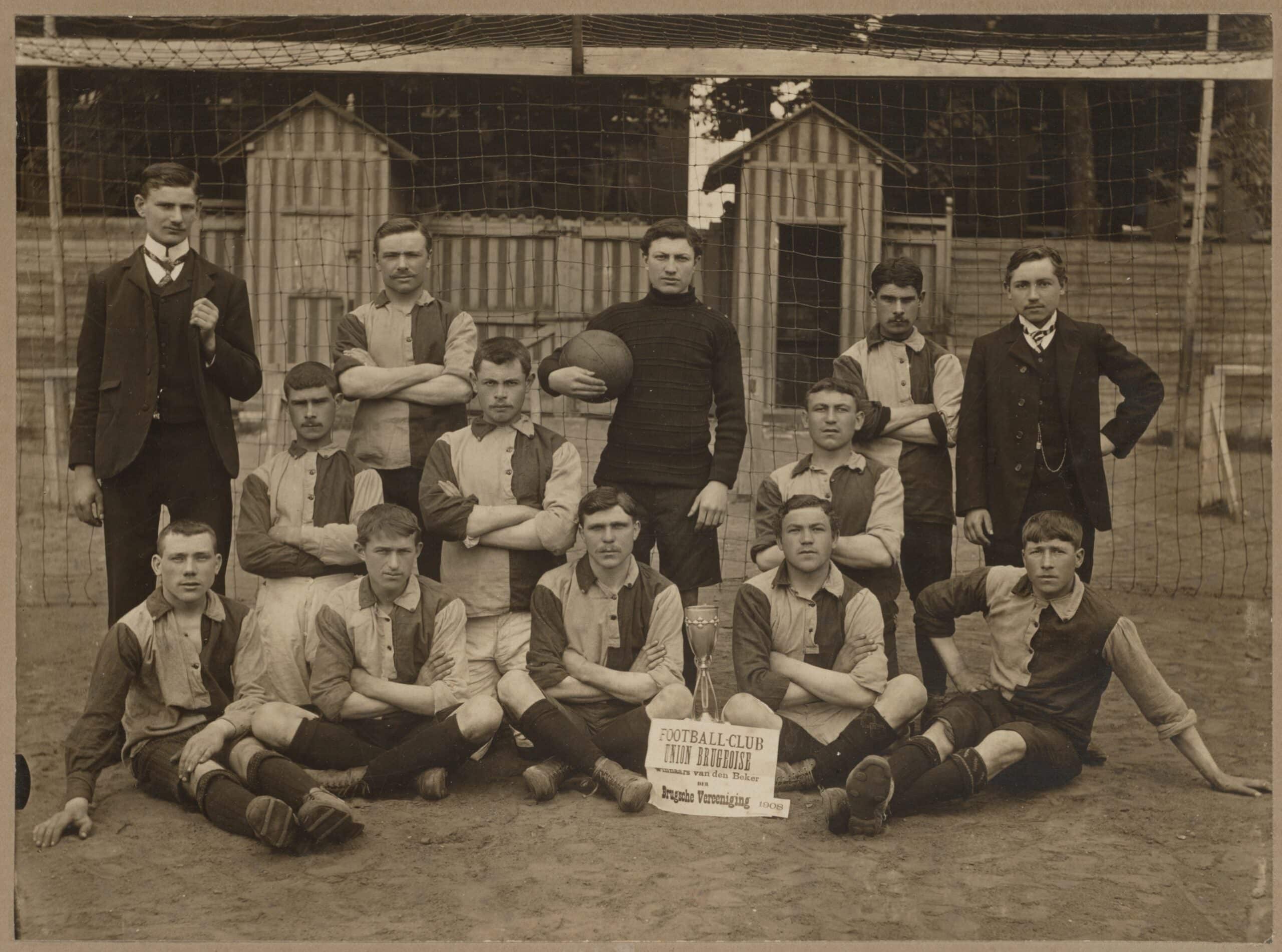

The Club Brugge team in 1908

The Club Brugge team in 1908© City Archives of Bruges / collection J.A. Rau, Bruges

Ultimately, it was a mix of players from different educational institutions in the city, along with former pupils of the Frères, who joined forces to establish the first football team in Bruges: the Brugsche Football Club. This merger team, which eventually took the name of one of its sub-teams (the Football Club Brugeois or FCB), is still regarded as the forerunner of today’s Club Brugge and 13 November 1891 as the official founding date. In 1926, FCB was given a ranking of 3 by the Belgian Union of Athletic Sporting Societies (Union Belge des Sociétés de Sports Athlétiques).

FCB opted for light blue jerseys with a dark blue, oblique band that ran from the left hip to the right shoulder. The choice of these two shades of blue was no accident. They were the colours worn by the rowing club, of which many “Brugeois” footballers were members.

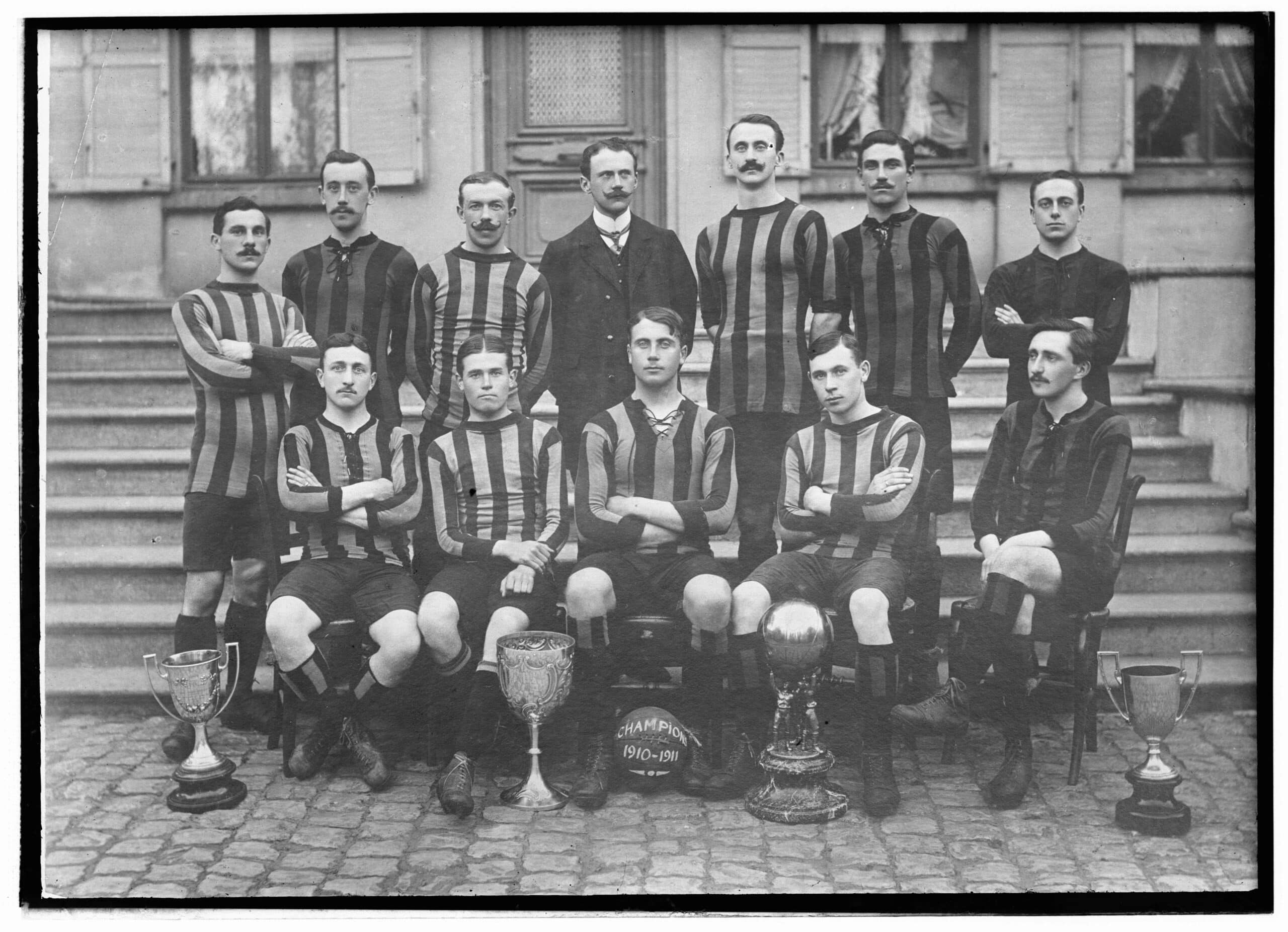

The Cercle Brugge team, Belgian champion in 1911

The Cercle Brugge team, Belgian champion in 1911© City Archives of Bruges / collection Brussele-Traen

The origin of Cercle is a simpler story. On 9 April 1899, the Association of Former Pupils of the Xaverian Brothers christened the club Cercle Sportif Brugeois. This prestigious association, which enjoyed the high patronage of an earl and a baron, had a mission to promote sports such as football, cricket, lawn tennis and athletics. From 1902, Count Charles d’Ursel, governor of West Flanders, granted his high protection to the “green-blacks”. Rapid Football Club, another team in the city, soon merged with Cercle, which was given a ranking of 12. The battle between the two Bruges football teams could begin!

Dilemmas, disputes and dust-ups

Despite the strong presence of liberal and non-denominational members on the board, FCB did not really have a pronounced ideology so it was difficult to categorise the team from a political point of view. Cercle, conversely, presented itself as a homogeneous, Catholic association. Education continued to play a background role, creating a permanent rift between the Frères and the Atheneum. Players who had studied at the atheneum automatically ended up at Club, those from the Xaverian Institute went to Cercle.

Exceptions often gave rise to bitter discussions and reprisals so when Raoul Daufresne de la Chevalerie, the second chairman in Cercle’s history, moved to Club in 1909 to act as a player and board member, the news exploded like a bomb. The city council strove for better relations, even creating the Entente Brugeoise, a committee with the remit of settling disputes between transfers. Yet, despite the committee’s efforts, clashes still occurred, leaving Bruges’ families in dire dilemmas.

FCB did not have a pronounced ideology. Cercle, conversely, presented itself as a homogeneous, Catholic association

There is, for example, the story of the Somers family, proud of five footballing sons at Club – until one of them decided to move to Cercle. Between 1949 and 1957, an exclusive agreement between Cercle and the members of the Xaverian Brothers’ sports department that prohibited any Cercle player from joining Club caused quite a bit of commotion.

Local matches could lead to trouble. A Club match against Cercle in 1925 on a pitch unworthy of the name (almost impassable due to snow and the subsequent, muddy thaw) would go down in history. Not so much because of the result, but because of a fight between the players and… the supporters (yes, even then).

Rivals showing solidarity

However, there were also beautiful moments. In 1923, a mixed team of Club and Cercle players played a demonstration match against a garrison stationed in Bruges to raise money for the victims of an earthquake in Japan. Three years later, when Bruges itself was hit by severe flooding, Club and Cercle again joined forces for a good cause.

Even when it concerned a national title, people were initially eager to wish the other team their congratulations. When Cercle was crowned Belgian champion in 1930, the Vice-President of Club was involved in the organisation of the victory festivities. The two football rivals collaborated on numerous occasions.

The two football rivals collaborated on numerous occasions

In 1927 FCB urged all its members to attend the funeral of Cercle player Albert Van Coile, who had fatally collided with the Tourcoing keeper during a match. FCB also played a friendly match against Tourcoing, the proceeds of which went entirely to the Van Coile fund. At the next home game in that year’s series, a collection was taken up amongst the Club supporters.

There were also clear signs of solidarity in the other direction. After the sudden death of FCB chairman Albert Dyserynck in 1931, Cercle organized a match against Racing Club of Ghent. All proceeds from that match went to the fund for a memorial monument to Dyserynck. That Dyserynck had been an active member of the Masonic Lodge was overlooked in this instance by the essentially Catholic organisation.

Frictions during the occupation

The relationship between FCB and Cercle during the German occupation of 1940-1944 was less cooperative. In the eyes of Club, Cercle had an advantage: the “green-blacks” benefited from the ban on football in the coastal areas because it allowed them to attract the best players from VG Ostende. In addition, few Cercle players were called up for work assignments in Germany, while those at Club found it difficult to escape that duty.

After the liberation, both teams experienced a hard brush with reality: because they had each played a friendly match against a German army team, they were suspended by the Royal Belgian Football Association until December 1944.

Still together... for now

The social separation of the teams’ founding period is, of course, much less rigid in 2022. The sporting balance of power has also evolved considerably. Cercle was the first football club in Bruges to win a championship (1911) and also took the title in both 1927 and 1930. Once this blossoming period ended, the team never bounced back. They dropped to the second division in 1946 and remained in the lower divisions for fifteen years. Since then, in the few better moments (also in the Cup) Cercle has mainly been commuting between the first and the second division and a satellite team of AS Monaco for a few years now.

Club had to wait until 1920 to celebrate its first national title but, since 1959, the blue-blacks have continuously been in the highest division. A second title, in 1973, took fourteen years to achieve but, since then, they’ve won eighteen titles. From 1976-1978, under the iconic Austrian coach Ernst Happel, Club were briefly the European top player and won two places in the finals (UEFA Cup in 1976; European Cup 1 in 1978) although, in both instances, Liverpool was always just a tiny bit stronger.

Half a century ago, the city of Bruges underwent some changes and financial problems forced both teams to face a stark reality. Cercle was forced to sell its sites and installations to the city council, after which Club spoke of discrimination. After rumours about a possible merger, the mayor at the time offered a way out: the brand new Olympiastadium would be built, in which both teams could compete.

In the meantime, the Olympiastadium (now the Jan Breydel Stadium) has become decrepit. Club has concrete plans for a new football temple next to Jan Breydel and Cercle is planning a site for its own stadium. If the location of the Cercle stadium is not approved, then the green-blacks can migrate to Club’s temple, which is yet to be built. Club had to make that promise in order to build a new stadium. The rivalry between Club, a large organisation popular far beyond Bruges, and the smaller Cercle, which in 2022 is mainly presenting itself as a ‘family association’, still exists, but the clubs remain bound together for the time being.