On September 23, 1408, a combined allied army of the duke of Burgundy, the count of Holland, and the bishop-elect of Liège marched against the people of Liège, who had erupted into an all-out revolt against their ruler. At the Battle of Othée, the Liégeois were utterly crushed and in the aftermath, the citizens of Liège were made to pay dearly by the victorious nobles, with the town stripped of its privileges and draconian punishments placed upon it. The retribution was so harsh that the bishop-elect of Liège earned the name “John the Pitiless”. But the real triumph belonged to another John, “the Fearless”, Duke of Burgundy, and Count of Flanders and Artois, who with this battle capped off a series of power plays which began with the very public assassination of his biggest political rival in France, Louis of Orléans. John the Fearless asserted himself as the dominant power broker in the Low Countries, showing the ever-restless towns what might happen to them should they rebel against his authority.

The inheritance of Philip and Margaret

The previous Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold and his wife Margaret of Flanders, had organised for their lands to be divided up between their three sons. Philip’s politicking had also ensured that the Duchies of Brabant and Limburg, conveniently ruled by his wife’s aunty Joanna, would pass to the family too, though not to their eldest son. In the space of two years, Philip, Margaret and Joanna all died, and, except for a mild bit of wheeling and dealing by the three sons, they respected the arrangements that their parents had made for them. The eldest, John, inherited the titles Duke of Burgundy, Count of the imperial part of Burgundy, Count of Flanders and Count of Artois. The second son Anton became Duke of Brabant and Limburg as well as Margrave of Antwerp, and the third son, Philip, got the hand-me-down titles – Count of Rethel and Nevers.

John the Fearless

John was born in 1371 into a world that was coming ever more under the thrall of his father. Not much is known about his early years, besides that, he grew up in a ducal residence on the outskirts of the capital of Burgundy, Dijon. John first accompanied his father Philip to Paris in 1384, but his first real act of historical significance was being married off as a 14-year-old to a woman 8 years older than him, Margaret of Bavaria. This was one half of the famous double wedding of brilliant diplomacy organised at Cambrai between the ruling families of Flanders and Burgundy, and Holland, Zeeland and Hainault.

John the Fearless (1371-1419)

John the Fearless (1371-1419)© Wikiwand

John would follow his father around on various trips to the French court in Paris and on military campaigns, learning by example the skills that would be necessary to juggle the various hats his father would eventually pass on to him. John didn’t go to the Low Countries until 1394, when he went with his mother to help in negotiations with the towns of Flanders.

Philip the Bold saw the value in non-tangible things such as honour and prestige, but was also playing a balancing act between his loyalty to France and his Flemish dependence on England, and the fact that they hated each other. He devised an idea that would aim at both gaining him great prestige, but also of bringing English, French and Flemish troops together. Philip organised a crusade and he chose John to lead it.

In April of 1396, a great host of Christian soldiers and retinue departed from Dijon and headed for Hungary, where the Hungarian king Sigismund was facing the rising threat of Ottoman Turks pushing westward.

The whole Crusade was a disaster, climaxing with Christian forces being overrun and slaughtered en masse at the Battle of Nicopolis. John, along with a bunch of other knights and Christian soldiers, was taken captive and held hostage for over a year until the towns of Flanders fronted up with enough money to pay his sizeable ransom.

The Battle of Nicopolis (miniature from the Chroniques of Jean Froissart, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France)

The Battle of Nicopolis (miniature from the Chroniques of Jean Froissart, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France)© Wikipedia

By being held captive for ages after a calamitous military defeat, John had managed to emulate the defining occurrence of his father’s younger days. Like Philip before him, John could now bulk out his medieval LinkedIn profile substantially. Before turning thirty he’d been taken hostage, held for a substantial time, and survived due to his fortitude and courage, never mind the hefty ransom raised on his behalf. In doing so he gained a tidy little epithet to stick on to the end of his name, just like his dad had done, and he would come to be known as Jean sans Peur, Jan zonder Vrees, John the Fearless.

Burgundy vs Orléans

John, therefore, had quite a formidable reputation already when he took over the ducal throne of Burgundy in 1404. But the position he inherited included not only the high political offices within the Low Countries and the French realm that came attached to the titles of Duke of Burgundy and Count of Flanders, but also serious political feuds, especially around the French royal court.

The King of France, Charles VI, was prone to insanity. During that time, the princes of the blood – who were the members of the French royal family – would compete against each other for control of the council of regency, a body set up to rule France in the king’s stead, during his bouts of craziness. Most crucially, control of the council of regency meant control of France’s purse strings.

Louis I, Duke of Orléans (1392-1407)

Louis I, Duke of Orléans (1392-1407)© Wikipedia

Philip the Bold, who had been the uncle of the King and chief amongst the blood princes, had siphoned funds off the royal treasury to Burgundy for years and spent the last years of his life immersed in a fierce stoush for fiscal and political control in France with his nephew Louis of Orléans. He was the brother of the king. Typically, like most politics at this time, and perhaps even still today, it was all very inbred. There were also varied layers of power politics going on in France, especially in the royal court. They included not only the ‘princes of the blood’, those with familial relation to the king, but also municipal administrators, clergy, and nouveau riche merchants. Many different players had their own agendas. In the course of challenging each other for the state’s wealth, The Dukes of Burgundy and Orléans also had to contend for the support and alliance of those different players.

Eugène Delacroix, Louis of Orléans Unveiling his Mistress, c. 1825–26

Eugène Delacroix, Louis of Orléans Unveiling his Mistress, c. 1825–26© Wikipedia

Louis of Orléans had a generally salacious reputation and seemed to have been a pretty loose unit. A decade earlier, in 1393, he had accidentally killed four dancers at a masquerade ball when, despite strict orders to the contrary, he brought a torch to a performance in which masked dancers in highly flammable costumes entertained the crowd. Unbeknownst to everybody, his brother, the king, was one of the anonymous dancers and was one of only two who survived. This became known as the “Ball of the Burning Men”, which would be an excellent name for a heavy metal symphony.

Louis was also a womanizer. He was apparently sleeping with his brother’s wife and as many other women as he possibly could. There’s a painting based on a popular, albeit maybe apocryphal story called Duke of Orléans showing his mistress, which depicts Louis lying on a bed with a woman, holding her dress up over her head, exposing her naked body to another man and asking him to judge her beauty. That man? He was her husband.

As soon as Philip the Bold shook off his mortal coil, in 1404, Louis of Orléans moved to take full control in France. He had soon organised a marriage between his son Charles, to the daughter of his royal brother Charles, Isabelle. What makes this spot of incest between cousins even more unpalatable is that there were strong and persistent rumours throughout France that Louis was having an affair with the girl’s mother; his brother Charles’s wife and the Queen consort, Isabeau of Bavaria. So basically he married his son to his lover’s and his brother’s daughter.

The canny part of Louis’ cunningly arranged wedding of his son to his niece was that the marriage came with a dowry of 300,000 francs. This was an incredible sum, and allowed him to further solidify himself as the most powerful person in France in the wake of Philip the Bold’s death. Louis now did what Philip had long been doing, and began lining his own pockets with the revenues of the state and gifts granted to him by the unfit king for whom he ruled. He became absolutely loaded.

The new Duke of Burgundy, John the Fearless, was therefore left bereft of the sort of income his father had enjoyed. He was also thrust into a very difficult political test which, if he did not succeed in, may see the destruction of everything his parents had built.

When his father died John could not just replace him and take over the central role of government, and especially now that Louis had already done so. But not all hope was lost. He had to bide his time and slowly gather support against the Duke of Orléans. It wasn’t all that difficult to find people who would support somebody up against Louis, as Louis was not that popular, especially amongst the wider public and especially considering his enthusiasm for raising new taxes and spending them on himself. His unpopularity is evidenced in the need he felt to send out a royal decree promising the greatest degree of punishment to anybody caught writing, distributing or fixing defamatory pamphlets against him to gates, doors or houses.

John began to position himself as the antithesis of Louis. Anti-tax, anti-sex scandal, anti-setting dancers on fire with torches, and of a generally more agreeable character. He began upping the ante, and basically lobbying the various people who mattered in the halls of French power. He took a tactical move from his father’s playbook, giving generous gifts of Burgundian wine that would amply sauce up potential supporters in Paris. He organised a meeting of very many vested interest groups there in early February 1405 and obviously sold himself exceptionally well.

John began to portray himself as the opponent (of Louis), as the champion of social discussions, of a “contract with the subjects”, of judicial reform in the name of the bien commun, and of fiscal reform against the extravagance of his rival. Prominent members of the Parlemant of Paris wrote memoranda noting how touched they were by John’s “affecting sympathy for the social situation of the people”. – Promised Lands, Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier

Religious schism

While this was all happening, another factor that came into play was the schism going on in the western church. In the first half of the 14th century, this meant Western Christianity divided itself into Team Avignon in France and Team Rome in Italy. This was resolved briefly in 1376 before reigniting again in 1378. It is all extremely murky, as different interest groups in different towns and cities across all of Western Europe supported different teams. In the Low Countries, people picked teams usually based on whether they were pro-England or pro-France, the two countries generally supporting opposite Pope teams due to their mutual enmity with one another. People also often switched sides based on which team their rivals supported or which side supported their rivals.

Antipope Benedict XIII (c. 1328-1423)

Antipope Benedict XIII (c. 1328-1423)© Wikipedia

By the 1390s most people were keen to see an end to the schism, but it was proving very difficult to get both Popes to step down in order to have a unifying vote, and this was definitely the case for Benedict XIII, the highly unpopular Antipope in France. Scholars and theologians around Paris in particular were steadfastly against him and began to publicly argue for why Benedict was, in fact, an Antipope. Remarkably this had such an impact on the highest ranks of the French court that in 1398 France withdrew obedience from him.

By the time of the conflict between John the Fearless and Louis of Orléans, the pope in Italy, Innocent III, had begun to enjoy an increase in popularity in France, whilst Benedict’s stock continued to drop. Louis, an unpopular man in France himself, continued to support Benedict XIII, despite the official position of the French crown. The shrewd political thing for Louis to do now would be to drop Benedict like the hot potato that he was. Instead, Louis maintained his support for him.

This worked to the advantage of John the Fearless, who supported Team Roman Pope, who was by now Innocent III. John, by doing this, could balance his role as a champion of the bien commun in France, having picked a particularly popular papal position preferred by plenty of people in Paris, with his role as the Count of Flanders. Team Roman Pope was the side of the English and therefore the side towards which his big, rich cloth towns like Ghent were most naturally inclined.

John was manoeuvring into a positive position. Be this as it may, however, it became clear to him that staying in Paris, in close proximity with his pissed off, cashed up, different Pope-supporting cousin who did not appreciate this threat to his power was no longer a good idea. So John packed up and headed off to the Low Countries in March 1405, just as his mother died and he officially became the Count of Flanders.

Count of Flanders

Upon becoming Count of Flanders, John the Fearless was, in the time-honoured Dutch tradition, presented with a list of grievances from the representatives of the Four Members of Flanders. John was well aware of the importance of the towns of Flanders. As well as having been present as a young man to help his mother in negotiations with them, John had also literally had his freedom purchased back by them after the disaster of Nicopolis.

So when the big towns demanded that John and his wife live in Flanders, that the administration of Flanders takes place in the Flemish language, rather than French, and take place in Flemish Flanders rather than the French-speaking part, and to hurry up and figure out a trade deal with the English, John agreed. Isn’t it pleasant for a change to see the Count of Flanders and the big towns actually agree with each other?

Margaret of Bavaria (1363-1423), Duchess of Burgundy, wife of John the Fearless

Margaret of Bavaria (1363-1423), Duchess of Burgundy, wife of John the Fearless© Wikipedia

The council of Flanders was moved from Lille to Oudenaarde, and then soon after to Ghent, and when he was out of the county his wife, Margaret of Bavaria, ruled in his place. When questions were raised to the council in Flemish, who spoke predominantly French, they were answered in Flemish. All of these concessions to the Flemish identity, as well as the extremely liberal approach John maintained as regarded Anglo-Flemish relations, are really indicative of how much he valued the stability of Flanders. He understood what a tinderbox it had historically been and that the embers had never burned out.

John also set about making and cementing alliances that would help him in his struggle for power in France. In the Low Countries, this was based on the work done twenty years earlier by his father, in the marriage alliance between the houses of Valois-Burgundy and the Bavarian branch of the Wittelsbach clan, who were the counts of Hainault, Holland & Zeeland. In July 1405, John arranged a triple alliance between himself, his brother Anton, who was the governor and future Duke of Brabant, and their brother-in-law, hailing from that Wittelsbach family, William VI of Bavaria, Count of Hainault, Holland & Zeeland.

In addition to this alliance, he also had the support of the counts of both Namur and Cleves, as well as the younger brother of the Wittelsbachs, a guy called John of Bavaria. We are going to hear a lot about John of Bavaria later in this episode and in the next one, so remember that name. He was the extremely contentious bishop-elect of Liège, at this point around 21 years old, and had a bright and very violent future in front of him.

About a month later, as an allied force was being assembled in Arras, John the Fearless received a summons from the king of France himself. In one of his less crazy periods, he seemed to be seeking an end to the conflict between the princes of the blood, and called John to take his place as a French prince in the royal court. This gave John an opportunity to go and pay homage to his liege lord as the Count of Flanders. But it also gave him a valid reason to go back to Paris and see if the seeds he had sown the year prior, promoting himself as the best alternative to Louis’ corrupt governance, had reaped any harvest.

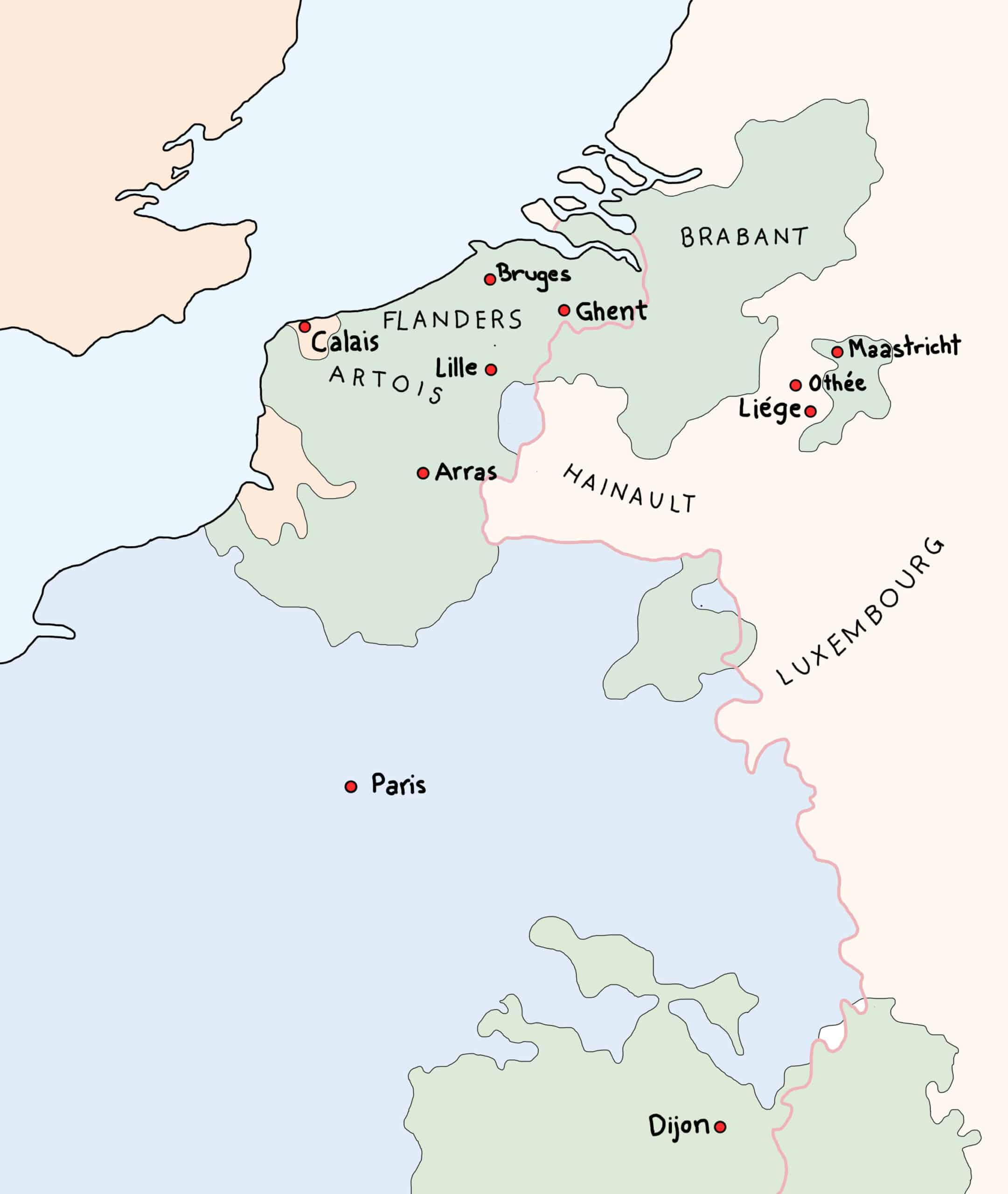

Map showing relative location of Liége, Othée and Maastricht to the Burgundian and French domains, by David Cenzer

Map showing relative location of Liége, Othée and Maastricht to the Burgundian and French domains, by David CenzerBack to Paris

Taking roughly a thousand men, secretly armed, so as to appear to be just a really bloody huge entourage, John set off from Arras for Paris on 14 August, 1405.

Louis of Orléans freaked out when he heard that John was on his way with this massive retinue from the Low Countries. Within three days he had left Paris and retreated to Melun, about 40km south-east of the capital. He took the influential Queen consort, Isabeau, with him. They then also made arrangements for the 10 years old dauphin, the heir to the throne, to be brought to them. On 18 August the young boy set off with his attendants.

John was still a day’s ride from Paris when word reached him about the dauphin’s

departure, and he set off early next morning to the French capital. There, he was told that the dauphin had already left. He and his men broke into a full gallop through the city, and heading south-east following the dauphin’s

trail, kind of like a medieval version of stalking someone’s Instagram story, they managed to catch up with him just before he reached Louis and Isabeau.

The dauphin

was not alone, but accompanied by another uncle, Louis of Bavaria, and other high-ranking nobles and guards. John approached him carefully, with respect and acknowledgement of the boy’s royal highness. He entreated the ten-year-old that the best and safest place for him was Paris, and that he had matters of personal interest to discuss with him. Louis of Bavaria spoke up, begging that John allow them to continue on. John, however, had no intention of letting such a prize go. He kicked out those in the dauphin’s retinue who were members of Louis of Orléans’ household and ordered everyone else back to Paris.

It turns out that John’s judgement was sound. On their approach to Paris, the other princes of the blood, namely the Dukes of Berry and Bourbon, clearly annoyed that Louis had acted so outrageously as to effectively steal the dauphin, came out to greet them, as did other important Parisians, members of the Paris university and other people we don’t care much about because, despite the nature of this episode, we are definitely not the History of France podcast.

Overall the general feeling was that John had done well, in ensuring the young heir’s safety. He was given over to the Duke of Berry and John and Louis continued their massive glaring contest. This time, however, they both began to assemble armies against each other, John being reinforced by his brother Anton and brother-in-law, the Bishop-Elect of Liège, John of Bavaria, who brought around 800 troops each with them. It is significant that, whereas in the past few centuries we have seen French and German armies marching into the usually fractured Low Countries, now with Burgundianisation, enough power had accrued under just a few people that a Low Country army could be bold enough to march on Paris.

After capturing the dauphin, John continued to work the political side of things, composing a document listing complaints against the Duke of Orléans and urging reform against his governance. Louis countered with his own set of pamphlets condemning John, and over the next five months, a propaganda war between the two ensued. Yet much like leaders today mean-tweet each other to no avail, these pamphlets did nothing to resolve the conflict.

Eventually, in January 1406, things petered out. John was granted a share of power with Louis, and was substituted into his father’s former position on the council of regency. In return, he gave up his policies of reform. Although this was a step forward for John, he still did not have anywhere near the primacy that his father had enjoyed.

One of the most important ways of cementing power is to create a base of support across different levels of administration. When Louis took over the council of regency, he also removed Burgundian-appointed people in various positions, on the council and in other roles, and replaced them with his own. Now, although John had a significant share of power, he was denied the ability to even the ledger of support below them; there were more people loyal to Louis than there were people loyal to John, on the council and in other administrative positions.

The next two years consisted of a truce between the two camps. We are not going to get into details too much because, honestly, we’ve spent so much time in France this episode that I’m almost certain that after this is recorded I’m going to go and get some foie gras and fromage and whip up a boeuf bourguignon.

A few significant marriage alliances were made which both parties could celebrate, and did so together. As mentioned, Louis’ son was to marry King Charles VI’s daughter, and then John’s niece, a very young girl and daughter of William VI the Count of Hainault, Holland and Zeeland, called Jacqueline of Bavaria, was married to Charles VI’s fourth son. Jacqueline of Bavaria is also going to come up again, we just have to let her grow up a bit and let an extraordinary life unfold.

In 1406, the fact that the actual ruler was a sometimes insane king, came once more to the fore, when John and Louis were both ordered to attack Calais and Bordeaux respectively, each of which was under the control of the English. The king then countermanded his own orders and left John unable to maintain payment to his troops. What is interesting in this event, as concerns our low-country focus, is that John simultaneously acted as a French prince, organising preparations for an attack on the English, while simultaneously acting as the count of Flanders, contradictorily working to guarantee that his West Flemish fortresses would remain neutral in any conflict.

A false peace, at best…

But despite the apparent cooperation and truce between the two, this was definitely not a stalemate, and they were both playing to win. At this stage, Louis had the upper hand. Firstly, John was strapped for cash, while Louis was absolutely rolling in it. Secondly, in 1406 Louis turned his attention towards the Low Countries, and began to put into motion several moves which were certainly designed to obstruct Burgundian power in the region.

In 1402 Louis bought the title of Duke of Luxembourg. When, in 1406, Anton finally became the Duke of Brabant, Louis let it be known that he intended to take possession of four castles, all of which were in Brabant but which he now claimed were rightfully Luxembourg’s.

Also, the growth of Burgundian and Bavarian power in the Low Countries had not been welcomed by everyone and at this stage the greatest opposition to it could be found in Guelders, and amongst the people of Liège, who in 1407 were in open revolt against their ruler, the bishop-elect and young, violent dude we said would come up again: John of Bavaria. Louis began supporting these two opposition movements against his enemies, and an alliance formed between Guelders and the rebellious people of Liège in October 1407 is suggested to have even been instigated by him.

Indeed, it seems that the Duke of Orléans was moving towards encircling John, cramping him and his allies in between France, Luxembourg, Liège and Guelders. If John wanted to protect his father’s gains, and all that he had inherited, he would have to take drastic action. And so drastic action is what he took.

The murder of the Duke of Orléans

On 23 November 1407, at about 8 pm, Louis of Orléans was returning from visiting Queen Isabeau, who had just given birth at the Hotel Barbette, in the northeast corner of Paris. One witness – a shoemaker, Jacquette – had been standing at her window, taking the washing in. She was also waiting for her husband to return home, and so had taken note of the mounted nobleman and his party’s approach down the street outside. He was playing with his glove and, she thought, singing. She turned to tend to her child, but suddenly heard an exclamation outside, and somebody shouting ‘Kill him!’. She looked again out the window and saw Louis on his knees on the street. A group of masked men, armed with swords and axes, had surrounded him and began to beat him savagely to death.

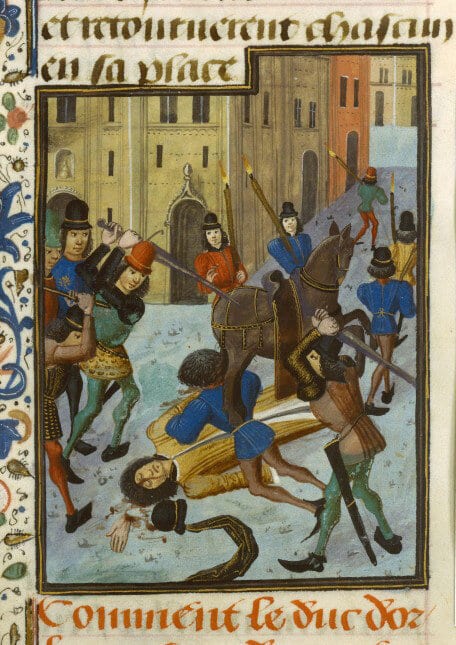

The assassination of Louis of Orléans by unknown author, probably ‘le Maître de la Chronique d'Angleterre’, ca. 1470

The assassination of Louis of Orléans by unknown author, probably ‘le Maître de la Chronique d'Angleterre’, ca. 1470© Wikipedia

According to the description given afterwards by the clerk of the court at the Paris Parlement:

They cleaved his head in two with a halberd so that he was knocked from his horse and his brains strewn over the pavement. One of his hands was cut clean off and, with him, they killed one of his valets, who had thrown himself on him to protect him.

It soon came to light that John had commissioned the whole thing. In the investigation, a person staying at John’s hotel was wanted for questioning, but could not be arrested without John’s permission. When he was asked for such permission, he was in council with other princes of the blood, and did not shy away from telling them the truth. He had had his cousin butchered, and now his other cousins were upset. Reportedly, he brushed aside the Duke of Berry and announced his need to visit the lavatory. Instead, however, he got on a horse and fled Paris. Once more, John went north. He had taken care of his rival in France, finally and utterly. John the Fearless was now also John the Peerless. He would now return to the Low Countries, and put paid to any question of his family’s dominance and dominion there.

To do this John would need to crush any opposition to his family and allies and capitalise on the fact that Louis’ death left them floundering without a major backer. At the moment this opposition was in Liège and Guelders.

Meanwhile in the Low Countries…

The people of Liège had not been happy folk for about a century. The lands of Liège straddled the River Meuse and lay roughly between the Duchies of Limburg and Brabant. They included some very old and important towns, such as the city of Liège itself and also Huy, the city from which the oldest known town privileges in the Low Countries originate. Unlike Brabant, Limburg or, indeed, Flanders, Holland and Guelders, Liège was not a fiefdom ruled by a count or duke, but a Prince-Bishopric, ruled by a prince-bishop. The prince-bishop held secular rule, owing his landed title to the Holy Roman Emperor, but also ecclesiastical rule, and was a high-ranking member of the Church. The title was not inherited, but rather made by appointment.

This difference did not make Liège exempt from the tumult of the 1300s that we should all be fairly familiar with by now. Just like the other Low Countries, the 14th century in Liège had also been one of class division, power struggles, rebellions and warfare.

In the first half of the 14th century, basic power-sharing mechanisms had been devised in Liège, between the bishops, the clergy, the towns and the patricians, similarly to what had happened in Brabant with the Charter of Kortenberg, and these were fortified in 1373, when the then Prince-Bishop, Jan van Arkel, agreed to the establishment of a council known as the XXII. The so-called Peace of the XXII allowed for a decision-making process intended to protect the people of Liège from abuses by the clergy and episcopal body of the prince-bishop.

After Jan van Arkel, the next bishop of Liège was Arnold II van Horne from 1378. He had been the bishop of Utrecht, which had also erupted in sectarian violence, and although he managed to somewhat reconcile the different parties in that conflict, Pope Urban VI moved him to take over Liège. The problem with this, however, is that the schism of the papacy had reinforced itself in 1378, so although Urban VI ruled from Italy, French cardinals had elected an Antipope, Clement VII, and he had set up shop in Avignon. The clergy in Liège elected their own bishop, and he was supported by the Antipope, Clement. So Liège saw a year of struggle between these two claimants, with Arnold coming out victorious and as the prince-bishop. He would rule for pretty much a decade.

In 1384 the biggest city in the Low Countries, Ghent, went into open rebellion against the count of Flanders, led by weavers and the second van Artevelde. The audacity of the weavers and other craft guilds inspired similar actions in other towns and cities across the region; just such workers took over the city of Liège at the same time.

In 1389 the death of Arnold opened up the title of prince-bishop, now making it ripe for the taking. In 1390, at the age of 15, enhancing the position of the Valois-Burgundy and Wittelsbach Bavarian families in the Low Countries, John of Bavaria became the Bishop-Elect of Liège. Remember that John of Bavaria was the brother of the Count of Holland, Zeeland and Hainault, and brother-in-law to the Duke of Burgundy.

But he did not become the prince-bishop. Because of the schism in the western church, any appointment was subjected to antipathy and uncertainty; if one group put up their candidate, the opposing group would find their own. John of Bavaria was, in accordance with the position of his family and of the Valois-Burgundians, on Team Roman Pope, who in 1390 was Boniface IX. He had approved the appointment. However, John of Bavaria was an awful ruler, and asserted his authoritarian approach from fairly early on. This rankled with the traditions of privileges and liberties that the people of Liège had acquired over the previous century. They rejected his appointment, and within four years had gone into revolt against him.

The revolting people of Liège

Prior to having his head cleaved in two, Louis of Orléans had been supporting this rebellion, as a part of his power plays against John the Fearless and push into the Low Countries. Louis, being on Team French Pope, had convinced Benedict XIII to also support the rebels of Liège. In 1406 the people of Liège elected a new regent and a new Anti-Bishop. A deputation was sent to Benedict XIII in France, to approve the appointment, and the new regent, Henry of Perwez, set about the conquest of the entire territory. Soon, John of Bavaria had access to only one fortress and the town of Maastricht, which was put to the siege at the end of 1409.

The siege was actually looking to be a successful one, and actually broke a few barriers in terms of warfare. The rebels used a tactic that would be adopted and become a mainstay on European battlefields up until today – near-continuous tactical bombardment. Indeed, before the first siege of Maastricht, gunpowder weaponry had only ever been used in conjunction with long-term starvation tactics, and there is only one recorded instance of bombardment breaching a fortification. Here, however, the rebels used possibly the entire arsenal of the city of Liège and, over the course of about a month and a half, sent over 1500 bombs into the walls and buildings of Maastricht. They were forced to abandon the siege due to the winter, and returned to the city of Liège.

Guelders enters the frame

John the Fearless’ brother, Anton, now governor of Brabant, was also facing problems. In our previous episode, we saw how the Duke of Guelders and Julich, William, had set out to take back territory and ensure his right to Julich. William had died without heirs, and so his younger brother Reginald IV became the new Duke. He shared his brother’s antipathy to Burgundian expansion and in 1406, supported also by Louis of Orléans, he had set about reclaiming territory from Brabant-Limburg. A year later he would push back against Holland for the town of Gorinchem.

So, when John the Fearless returned to the Low Countries after having had his main political rival, Louis of Orléans, butchered in the street, this is roughly the state of things that he came back to. John of Bavaria was in serious trouble and crying for help, and John the Fearless had begun to assemble an army to come to his aid, but he was obviously more concerned with helping his brother against Guelders, because he sent his army there first. They managed to subdue the Guelderian offensive.

Back to Paris (again)

John then returned to Paris, with his brother Anton, to deal with the post-murder political situation which was devolving into what would become a civil war. According to the chronicler, Enguerrand de Monstrelet, he had to present himself before the king. When John entered Paris in early 1408, he was given a hero’s welcome by the people of the city. While in Paris he was always armed and stayed in a fairly secure tower. He employed a theologian named Jean Petit to argue his case and what he presented became famously known as the Justification. Petit argued forcefully, using quotes from scripture, that the Duke of Orléans was a corrupt and treasonous individual, had eyes on complete power, and that John’s hand had been forced to conduct such an egregious deed so as to protect the king’s personage. Anyways, didn’t Louis of Orléans try to kill his royal brother at the Ball of the Burning Men, all those years before?

Somehow John came out of this alright with the king. In 1409 Charles VI would absolve him of the crime of killing his brother. But for now, having argued his case, John had to return to deal with the rebellions in the Low Countries.

United Lowlander force

By the middle of 1408, the two biggest rulers in the Low Countries, John the Fearless and William VI of Hainault, Holland & Zeeland, had joined forces with John of Bavaria to crush the Liège revolt. Although the leaders of the rebellion were facing such a combined threat, they were clearly shrewd, as they set about running a disinformation campaign, aimed at causing divisions and uncertainty amongst the forces allied against them. They forged letters from the French king to John the Fearless, telling him to stop the offensive immediately; they forged letters from John of Bavaria with content designed to weaken their bonds of alliance; they also sent people dressed as pilgrims out to spread words of how Maastricht had fallen and that John of Bavaria had fled, hoping to further incite support for their rebellion. Then they sent other agents into Maastricht itself, to spread the word that there was no sign of any army coming to help them.

During these months the French crown was attempting to negotiate peace, but John had several reasons to want a military resolution to the matter. The state of the French court was a major concern for him, as always. Supporters of the murdered Louis had banded around the son of Louis of Orléans, into a faction that would become known as the Armagnacs, and it was looking increasingly likely that John would be forced to make battle with them in the future if he wanted to maintain power in France. For him, the failure at Nicopolis over a decade prior had been the only major military expedition in his life, and although he had doubtless learned from it, he might have felt the need to ‘sharpen his axe’, so to speak, and get a little bit more experience into himself and his troops, before facing off against French Armagnac armies. Taking on the bomb-friendly rebel armies of the Liégeois could provide a perfect opportunity for that. In fact, John seems to have been observing the tactics of the rebel army already. When he did later fight the Armagnacs, he appropriated the continual bombardment tactic which they had pioneered at Maastricht, and his forces would use it to great effect.

Another thing that John would have had to consider is what effect a successful rebellion in Liège might have on the rebellion-happy workers in his Flemish towns. If he didn’t crush this now, the infectious liberal ideas of the past might flare up once more amongst such factions as the weavers and the fullers. As we know, when towns like Ghent went into rebellion, they didn’t mess around with it and caused no end of strife for their counts.

So here in the Bishopric of Liège in late 1408 is a coming together of all these interesting undercurrents which we have been wading through so far in this series. Workers guilds fighting for their rights, nobles in the Low Countries allying with and fighting against the crowns of their larger neighbours as suits their particular needs and interests, the battle for control of everyone’s everlasting souls, and a whole lot of incestual feuding and in-fighting at the highest level of politics.

Even though John remained a participant in negotiations deep into 1408, he continued to build up his allied forces at Tournai, and then shifted them into Brabant in mid-September. Finally, on 20 September he ended negotiations and went off to begin an offensive. Together with his brothers-in-law, he moved his army into Liège. A last-ditch attempt by King Charles VI to broker peace produced an ambassador to John with the king’s direct order to cease immediately, on pain of great punishment. John argued with the ambassador that he had come too close to be able to stop without incurring great shame. He then convinced the ambassador to even join him in the fight. Given that the ambassador had secretly brought along his armour anyway, this was probably the expected outcome.

The Battle of Othée

On 23 September 1408, the combined larger armies of John the Fearless and William VI of Holland, supported by John of Bavaria and other high-ranking Low Country nobles, knights and infantry, met arms with the rebel army of the Liégeois, in what has become known as the Battle of Otheé.

Monument built to remember the Battle of Othée by Eric Vyncke, 2006

Monument built to remember the Battle of Othée by Eric Vyncke, 2006© Wikipedia

All those years ago at Nicopolis John had failed due to not having the right people around him, not knowing who to listen to, and also by falling victim to being too brash, seeking glory too gallantly, and not being patient enough. A disordered cavalry charge of uppity knights had ended in disaster at Nicopolis. Here, despite again having the far greater force, John did not fall into the same trap of vainglory. Instead, he set up his forces to defend an attack. When the attack was not forth-coming, he consulted with his other captains, and decided upon a steady march forward. When the two sides met, the Liégeois rebels were absolutely destroyed, and the high discipline and well thought out approach of John and his council proved crucial. John’s tactics would be a blueprint for all future engagements his troops would undertake.

In fact this day was crucial to the overall reputation of John the Fearless, which had taken some battering following the assassination he had contrived, but remained extremely popular amongst the many who had detested the Duke of Orléans. Enguerrand de Monstrelet, a Burgundian chronicler wrote of his conduct during the battle that it:

Was such that he was praised and honoured by all the knights and others of his company; and although he was frequently hit by arrows and other missiles he did not, on that day, lose one drop of blood.’

Old Johnny No Fear.

Monstrelet continues:

When he was asked, after the defeat, if they ought to siege from killing the Liégeois, he replied that they should all die together, and that he had no wish for them to be taken and ransomed.

And this is where things get a little gruesome. For John the Fearless this action was as much about his wider political goals as it was about assisting his brother-in-law and ally. An example had to be made of the rebels, not only so that possible rebels in his other territories remained afraid of the consequences, but also so that the Burgundianisation of the Low Countries could continue; he couldn’t afford to allow anything to threaten the centralisation that his father had commenced, and the rebellion in Liège had done just that.

Instantly the revolt, which had been waging for nearly 15 years, was crushed. The victors swept up the countryside and approached the city of Liège, which was the epicentre of the rebellion. Instead of entering it they camped outside and ritualistically decapitated ringleaders whom they had caught. Within the town walls, the rebellion was also being cast asunder. Members of the clergy who had supported Team French Pope and the rebellion were drowned in the River Meuse. Drowned because, as Ecclesiastes, their blood was not to be spilt. Drowning though, drowning was fine… John of Bavaria would from now on be known as John the Pitiless, which seems apt.

500 hostages were demanded from the city, and these were spread out between the victors and sent off to various places, many of them for years. In October 1408 John convened a great assembly of the Low Country ruling elite in Lille. Chief amongst all in attendance were the leaders of the Low Countries, brought together first by that double wedding way back in the 1380s, but now also bound tighter by an allied victory they had enjoyed together, one that had solidified their collective dominance of the region under the chief leadership of John the Fearless. This included both of John’s brothers, Anton and Philip of Nevers, William of Bavaria, count of Holland and his younger brother, John of Bavaria, and also William of Namur.

Here, they passed judgement on Liège and set the terms of its defeat. These were extremely harsh. According to these terms, no privileges could be granted to the Liégeois without both John the Fearless and William of Bavaria’s approval, they and their successors could pass by the River Meuse with or without troops, and their minted currencies were to be legal tender in Liège from now on. Furthermore, a few fortresses were to be destroyed, a church to be built, and all guilds in Liège were abolished, which…can you imagine if the Counts of Flanders had managed to pull that one off? Finally, a huge indemnity of 200,000 French crowns was to be paid to John and William.

In fact, so harsh were the terms that John the Pitiless, the victorious Bishop-Elect of Liège, was extremely upset, and turned into one of the greatest opponents to these new restrictions on his he and subjects. He lobbied and complained and managed to get some of the forfeited privileges back, and was able to delay payment of the reparations. He would, strangely enough, continue to petition for his subjects’ rights, right up until 1417. In 1417 everything would change drastically, but that is for another episode.

Sources

- The Chronicles of Enguerrand de Monstrelet

- Reputation and Representation in Fifteenth Century Europe, edited by Douglas L. Biggs & Sharon D. Michalove

- John the Fearless: The Growth of Burgundian Power, Volume 2 By Richard Vaughan

- The Promised Lands by Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier

- Magnanimous Dukes and Rising States: The Unification of the Burgundian Netherlands, 1380-1480 by Robert Stein

- A History of the Low Countries by Paul Arblaster