Filmmaker Johan Van Der Keuken Shows Social Commitment Through an Experimental Lens

With one eye, Johan van der Keuken looked at the world around him, while the other peered through the viewfinder of the camera. A new retrospective draws attention to a prolific but underexposed Dutch filmmaker.

If there is a thread running throughout Johan van der Keuken’s (1938-2001) cinematic oeuvre, which spans more than fifty films and four decades, it is this: it combines social commitment with a pronounced attention to form.

The Amsterdammer captured people on screen with great commitment, who often find themselves in the lower levels of society. At the same time, he was convinced that the cinematic framework he imposed on reality is a fictional construct. Rather than disguising it, he drew attention to the medium he was working with – by dealing associatively with editing, sound and music. This vision is reflected in the retrospective See, Look, Film that can now be viewed at the Brussels Cinematek, in collaboration with the film magazine Sabzian.

Herman Slobbe in 'Blind Child' (1964)

Herman Slobbe in 'Blind Child' (1964)© Johan van der Keuken / Sabzian

Everything is form

At the start of his career, in the sixties and seventies of the last century, Van der Keuken mainly made short documentaries about his immediate surroundings. The best known of these is Blind Child (1964), about the blind boy Herman Slobbe. In that film, Van der Keuken not only pays attention to his subject but also has an eye for the form of the medium he works with, says Gerard-Jan Claes, artistic director of Sabzian and a filmmaker himself. As soon as Van der Keuken captures Herman with his camera, the latter becomes a form. At the end of Blind Child, the filmmaker literally conveys this with a voice-over: “Everything is a form. Herman is a form.”

For Van der Keuken, attention to form is a way of resisting claims of depicting truth that some documentary makers make: “Even though it is documentary, it is not true, it is a form, matter that has been edited and processed, fiction.” Van der Keuken thus distances himself from conventional fiction film by disconnecting from the production system and picking up a camera himself. But he also distances himself from the classic documentary, by openly unmasking the construct of the medium he works with. “Those ideas about ‘truthful cinema’ were prominent in the influential cinema vérité movement in France in the sixties,” says Claes. Films such as Chronique d’un été (1961) by Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin are an exponent of this. “Although that film also opens with doubts about whether a conversation can be filmed ‘naturally’, as if the camera were not present.”

'Even though it is documentary, it is not true, it is a form, matter that has been edited and processed, fiction.' – Johan van der Keuken

From the seventies onwards, Van der Keuken also began making longer films. These were not limited to the Netherlands or Paris but took place all over the world. An example of this is the North-South trilogy, with the titles Diary (1972), The White Castle (1973) and The New Ice Age (1974), in which Van der Keuken always connects a situation in the Global North to the Global South. In The New Ice Age, these are Peruvian miners and factory workers from Groningen, who together form the subject of a meandering critique of globalized capitalism. Giving “ordinary people” a voice was an important substantive motive for the leftwing progressive Van der Keuken. Yet the North-South trilogy is not a political pamphlet. The films largely revolve around a formal game. Van der Keuken makes his viewers aware that they are watching a film, but one that is closely linked to a social reality of people who also exist outside the film.

In The New Ice Age, Van der Keuken opts for a very associative and rhythmic montage that brings abstract analogies to the surface – which can also be interpreted politically. “Johan van der Keuken’s editing is therefore one of the things that most defined him as a filmmaker,” says Claes. Van der Keuken based himself on filmmakers such as Alain Resnais, but he also felt conceptually related to abstract painters like Piet Mondrian. Van der Keuken himself was more in favour of the concept of collage than editing. According to him, collage does not give the impression that as a filmmaker you know all the possibilities of an image. A cinematic collage may evoke meanings, but they are never definitive.

Van der Keuken based himself on filmmakers such as Alain Resnais, but he also felt conceptually related to abstract painters like Piet Mondrian

This unconventional method becomes clear in a scene in The New Ice Age where Van der Keuken portrays a Groningen girl writing a letter to her boyfriend. A voice-over reads the letter to the viewer and does so five times in a row – which leads to a rhythmic repetition. In the meantime, Van der Keuken films the girl’s bedroom with his mobile camera, making a kind of circular movement. By linking this auditory and visual repetition, all kinds of associations arise that have not been thought out in advance. For example, the word “television” coincides three times in the text with a poster of a Cadillac. Van der Keuken puts jazz music under the voice-over, specially composed by Willem Breuker for the film. Image, text and music together become a solid whole.

Aesthetics versus ethics

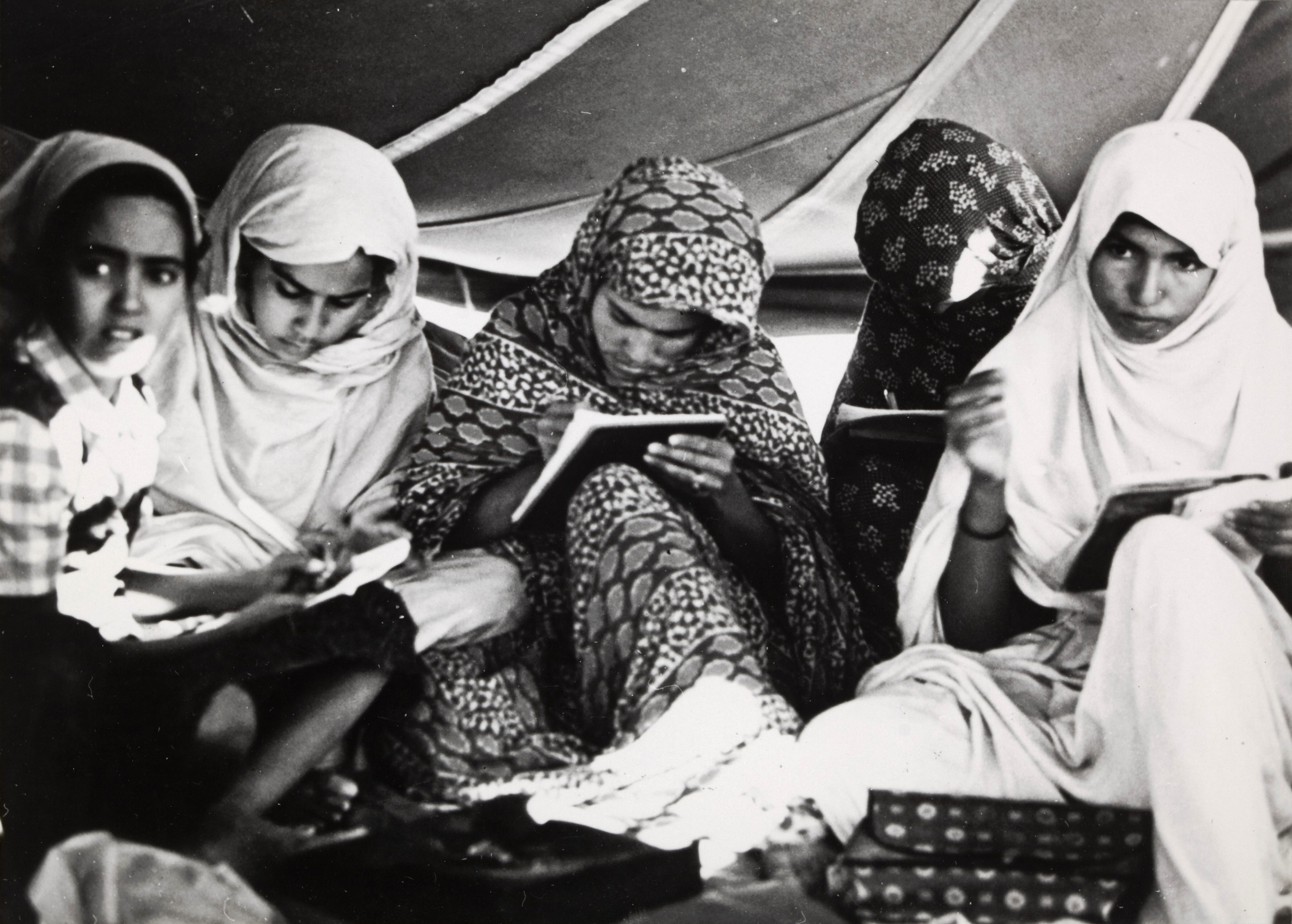

Such a rigorously applied playing with form can have a downside. The further you go as a filmmaker, the further you move away from the social arena, according to Van der Keuken, where, in his words, “not only concepts are brandished, but there is also hard struggle.” Van der Keuken was aware of this. For some films, he therefore resorted to a more sober style. In The Palestinians (1975), about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he says he allowed himself less room for manoeuvre than usual. The people he portrayed had to be given a more prominent role. Film critic Jacques Kermabon wrote how Van der Keuken portrayed the Palestinians with a certain admiration: “He films them directly, from as close as possible, with a concern for universality.”

Still from 'The Palestinians' (1975). Every shot in Van der Keuken's films was carefully chosen.

Still from 'The Palestinians' (1975). Every shot in Van der Keuken's films was carefully chosen.© Johan van der Keuken / Sabzian

In doing so, Van der Keuken raised an important moral question. Because who has the most important voice in films: the maker, or the people who are filmed? Gerard-Jan Claes calls this the tension between ethics and aesthetics. He goes back to Herman Slobbe, who in Blind Child is both a form constructed by Van der Keuken and a human being who exists outside the world of film.

Return to Amsterdam

Van der Keuken’s friend, writer Bert Schierbeek, once wrote that he saw life as “777 stories that take place at the same time”. The filmmaker took this philosophy to heart in Amsterdam, Global Village (1997). The more than four-hour film he made at the end of his career is his magnum opus.

Van der Keuken’s Amsterdam is the centre of a globalised world in which numerous characters from multiple continents come together. Like the Bolivian Roberto, who goes to Amsterdam for love. Van der Keuken not only filmed him in the Netherlands but also followed him to his native village in Bolivia. The filmmaker based this on the wise insight that if you want to say something about the Netherlands, you have to start abroad.

In terms of form, Amsterdam Global Village is equally ambitious. As is often the case, Van der Keuken did not opt for linear editing but rather composed his film through circular movements. His camera travels from Amsterdam to destinations such as Bolivia, Sarajevo and Thailand to circle back to the Dutch capital again and again. For Van der Keuken, it was as if Amsterdam – and the world by extension – was built up like an onion, the individual layers of which he can expose with his film camera. Devoted to that camera, is the filmmaker himself, who casts images from complex reality.

The Johan van der Keuken retrospective runs until 28 February at Cinematek in Brussels. A collection of texts by and about Van der Keuken can also be consulted free of charge on sabzian.be.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.