Finding a New Role for Flanders’ Historic Theatre Scenery

Flanders has several significant collections of historic theatre scenery, including Europe’s largest collection, in Kortrijk. But the extent and value of this heritage have only recently been recognised, and work is needed both to preserve it and to figure out how it can best be used.

In traditional stage design, which was widespread until the early 20th century, theatre scenery aimed to create an illusion of reality. Painted backdrops used trompe l’oeil effects to faithfully represent interiors or landscapes, while hangings or flat panels to the side of the stage created a sense of foreground and depth. This painted scenery could also be functional, such as a flight of stairs actors could climb, or three-dimensional props such as columns, trees or walls. The lighting was fixed, calculated to complete illusion and heighten the atmosphere for the performance.

Large city theatres usually had a repertoire of sets, which were used time and again by local and visiting companies: a town square, a palace, a drawing-room, a tavern, a garden, a dungeon, and so on. Sometimes the style would be vague, such as a forest glade in summer or a Flemish town square in winter, but there were also sets for precise locations, such as Paris or Venice, that appeared frequently in the plays performed.

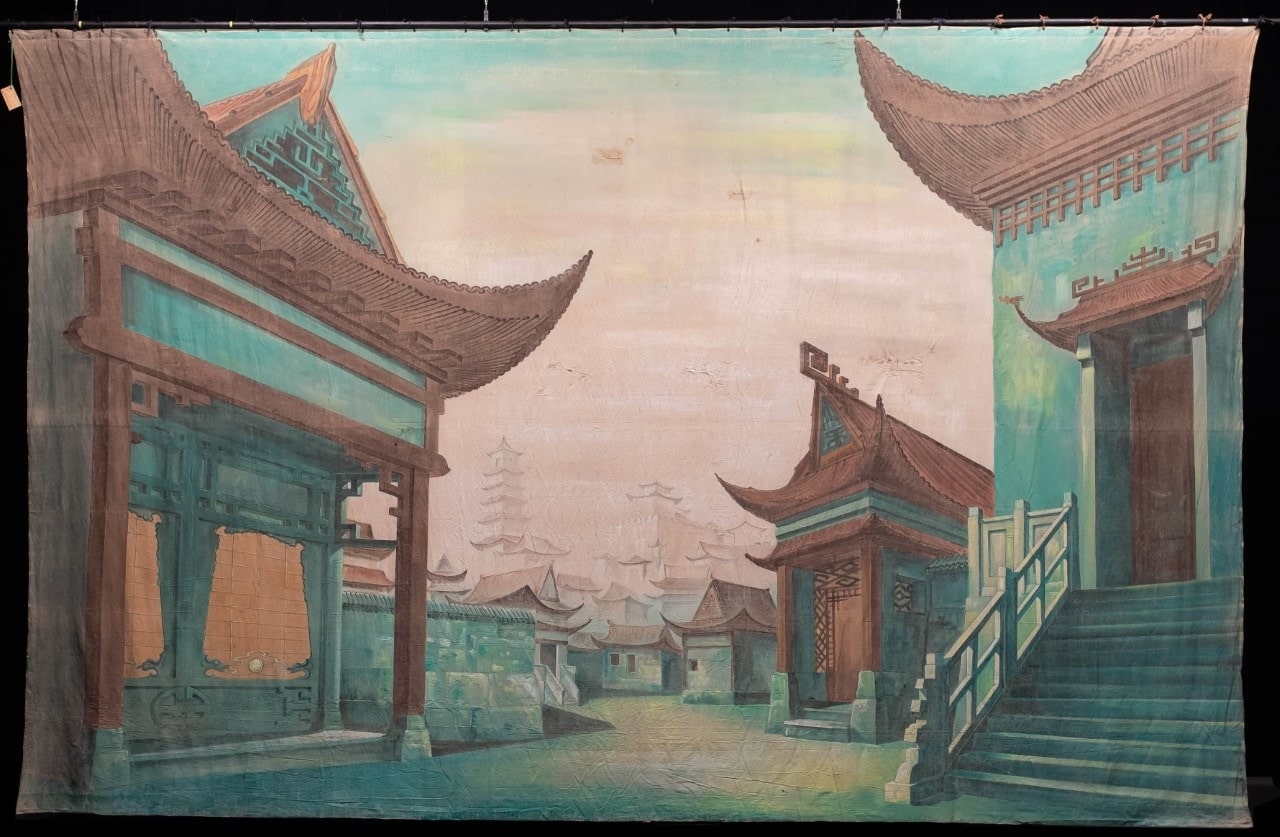

W. Beyne & Sons: backdrop 'Chinese street/Peking', before 1962

W. Beyne & Sons: backdrop 'Chinese street/Peking', before 1962© Collection ShowTex / photo: Charlotte Van Kerkhoven

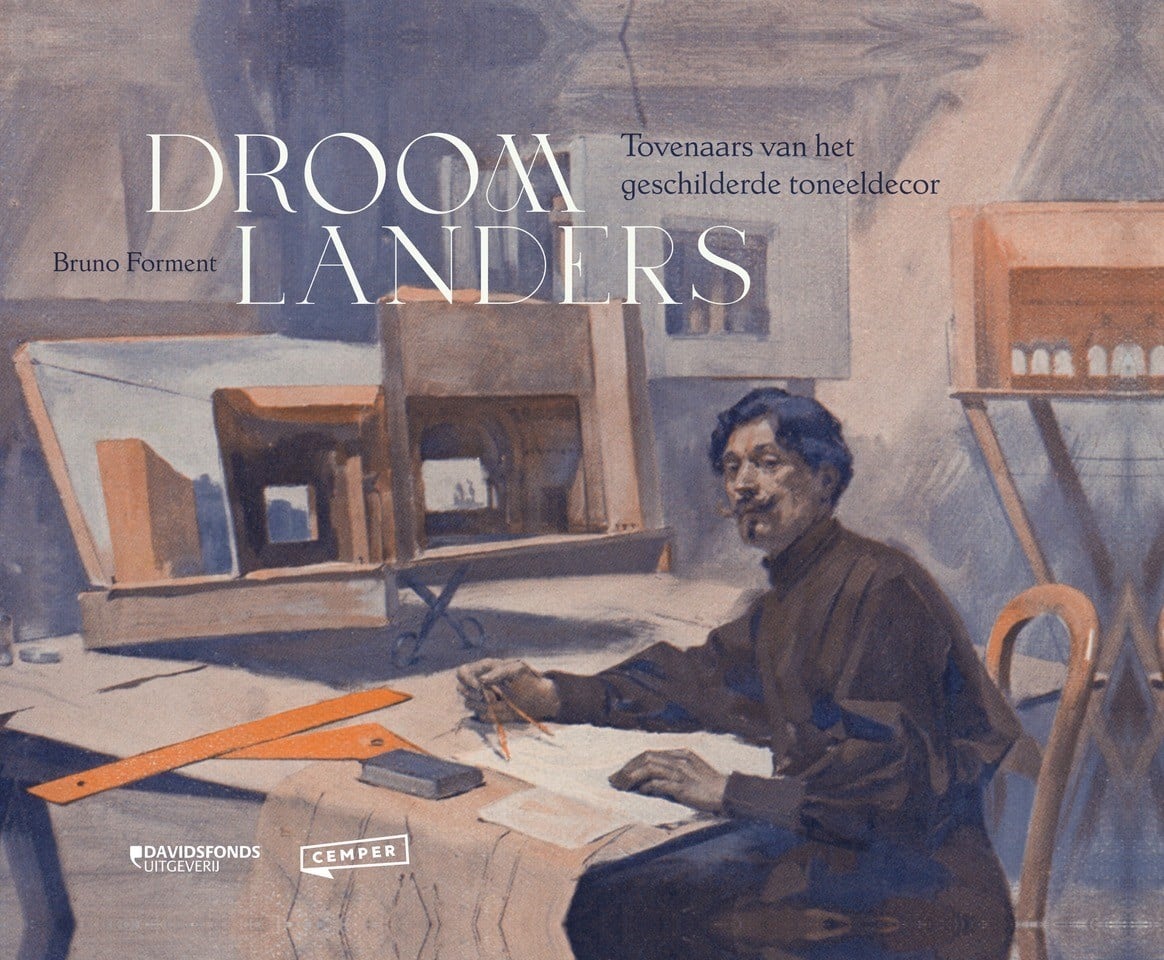

Albert Dubosq

This illusionistic approach to theatre scenery started to change at the end of the 19th century, when new ideas about performance started to rub against modernism in art and architecture, and realism made possible by photography and cinema. From this point on, the weight of creating stage reality gradually shifted to the performers, supported by more active lighting, while the scenery became more suggestive and symbolic, if not completely abstract.

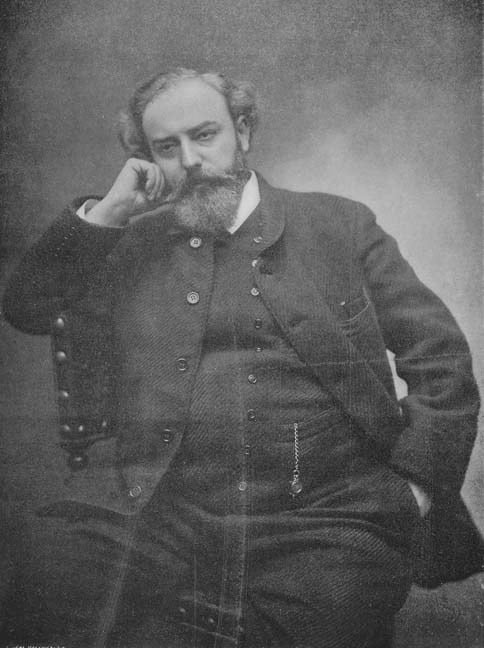

Portrait of Albert Dubosq by Georges Dupont-Émera, c. 1906

Portrait of Albert Dubosq by Georges Dupont-Émera, c. 1906© Wikipedia

Yet this change took time, and when Kortrijk set out to equip its prestigious new city theatre in 1913 it opted for tradition and commissioned a repertoire of 12 sets from the workshop of Albert Dubosq, Belgium’s foremost illusionistic set painter. These were delivered in 1920, when the theatre finally opened after the disruption of the war. The vividly coloured linen backdrops, painted with a mix of pigment and glue known as distemper, were up to 14 metres wide and 10 metres high, while the flats were up to 7.5 metres high. The repertoire included sets for public squares in the present and Middle Ages, a park that could pass as a garden or a forest, a mountainous landscape, rustic and palatial interiors, and a prison.

The next year Dubosq supplied Kortrijk with a Greek temple set, and a second-hand Roman palace, originally built for a Comédie-Française performance in Tournai. A series of opera sets followed, specifically for visiting productions by the Grand Theatre of Ghent. These included a comprehensive set for Bizet’s Carmen; two sets for Delibes’ Lakmé, one of which is a striking oriental forest; and three complete sets for Verdi’s Aida, including a grand Egyptian temple. Then there were sets for the local Vlaamse Zonen (Sons of Flanders) company, which performed operettas in Dutch.

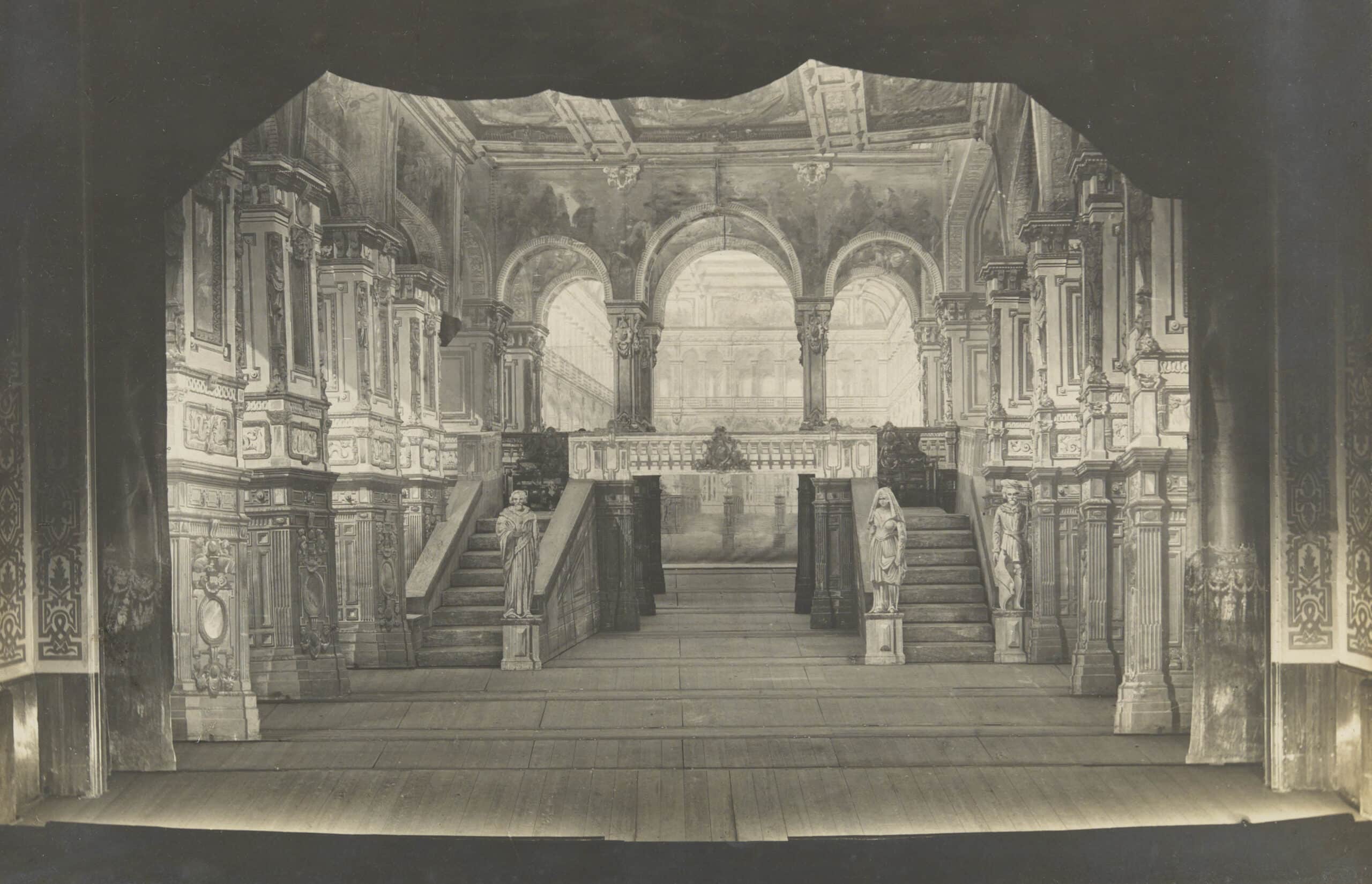

Albert Dubosq: 'Roman Palace', City theatre, Kortrijk, 1913

Albert Dubosq: 'Roman Palace', City theatre, Kortrijk, 1913© City of Kortrijk

Need for preservation

An enduring local interest in operetta is one reason Kortrijk did not discard its old sets as the fashions in performance changed. An old-fashioned look suited these light musical entertainments, and so the sets continued to be used throughout the 20th century. Meanwhile, a feeling lingered that these were somehow expensive, high-quality items, even if the details were forgotten. After a time, the sumptuous sets simply became known as the operetta sets.

When music and theatre historian Bruno Forment first saw them in 2008 he recognised their lineage and their value. Comparing Kortrijk’s collection to others in Europe, he concluded that there was nothing to match it for size or quality. Worldwide, the only collection of illusionistic theatre scenery to surpass it is at Northern Illinois University in the USA, a legacy from Oscar Hammerstein’s Manhattan Opera Company and various Chicago opera houses.

René Philastre & Charles Cambon: 'Palais Renaissance' in the setting for 'La Dame blanche', Grand Théâtre, Ghent, 1841

René Philastre & Charles Cambon: 'Palais Renaissance' in the setting for 'La Dame blanche', Grand Théâtre, Ghent, 1841© photo: Bernard Jacobs, 1900-12, Ghent University Library

Forment started to research the collection, and to organise it after decades of haphazard storage. He also looked into preservation issues, such as removing dust, stabilising the distemper and repairing damage to some of the items, work that is still ongoing. Meanwhile, 164 of the flats were backed with asbestos-coated paper as a fire safety measure, and so needed to be isolated pending treatment.

From an academic point of view, the sets are an invaluable link to past theatrical practice, and not just for the way they were used in Kortrijk in the 1920s. Some of the sets can be identified as copies of Dubosq’s work for other Belgian theatres, in Brussels, Ostend, Ghent and Antwerp, in the early years of the century. But stylistically they reach even further back, reflecting the 19th Century Parisian theatre tradition in which Dubosq trained.

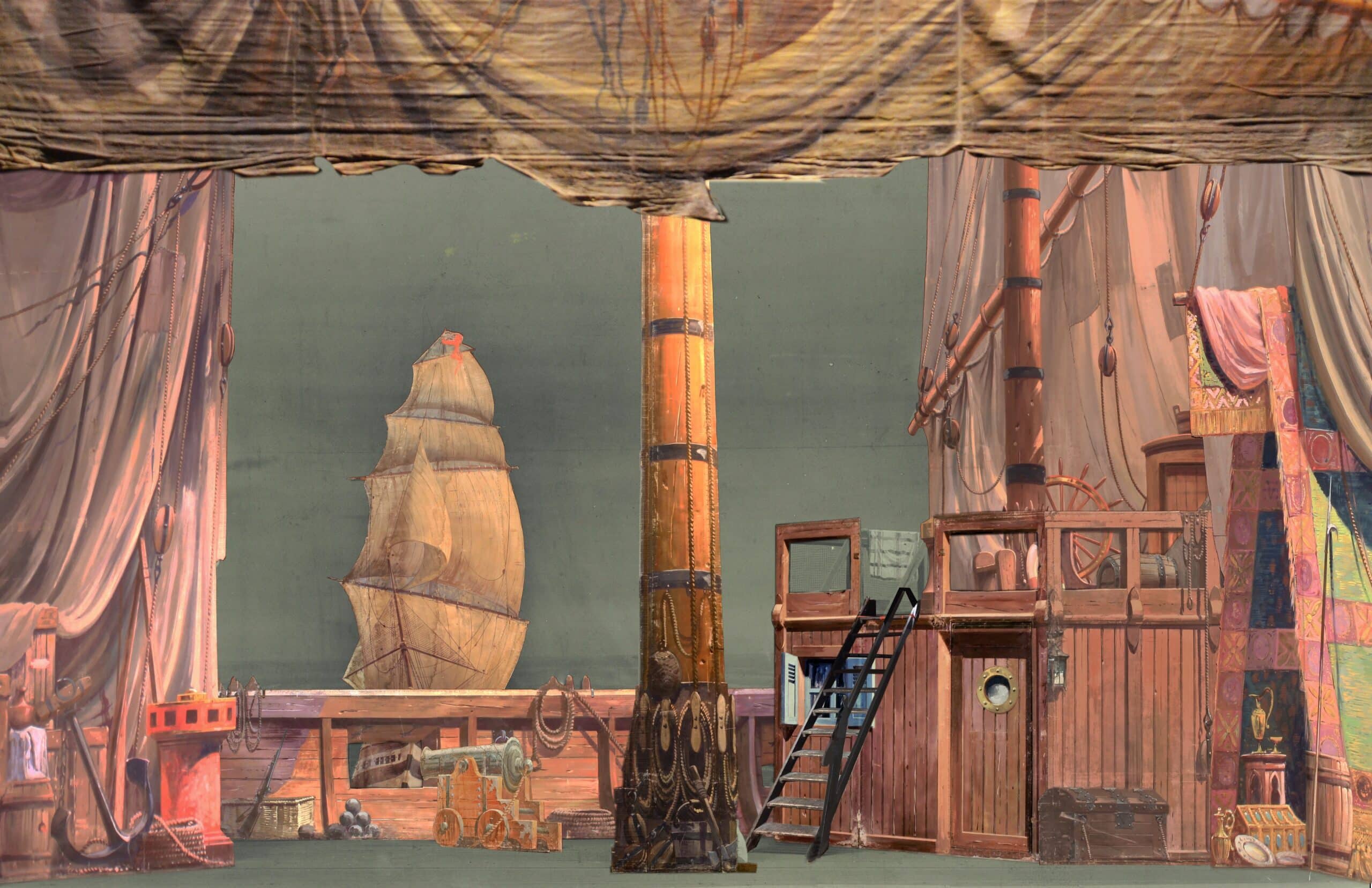

Joseph Denis: 'Bateau' for 'Surcouf', City theatre, Kortrijk, 1923. Reconstruction by Bruno Forment on the basis of preserved scenery and a set photo by Gustaaf Lievens, ca. 1923

Joseph Denis: 'Bateau' for 'Surcouf', City theatre, Kortrijk, 1923. Reconstruction by Bruno Forment on the basis of preserved scenery and a set photo by Gustaaf Lievens, ca. 1923Being able to reassemble the sets on stage can tell us more about how a performance looked than the models, sketches and photographs (generally black and white) that are in the archives. And since opera productions stayed faithful to the original design of the Belle Époque, examining Kortrijk’s 1921 set for Lakmé can tell you a lot about how the premiere looked at the Paris Opéra-Comique in 1883.

Masterpiece list

Bringing this heritage to the public is a little trickier, since the sets need to be assembled and properly lit to be appreciated, and only take on their full significance with a performance. The recognition they have received in recent years has not always helped in this respect. Five of the finest sets were placed on the Flemish heritage masterpiece list in 2018, which means they can now only be used in exceptional circumstances.

But little by little, the Dubosq sets are finding a role. The Roman Palace set was restored in 2012 for a performance of Johann Christian Bach’s opera Artaserse, put on by the Royal Conservatory of Antwerp. This was both entertainment for the public and an academic research project. The set was then re-assembled in the Kortrijk theatre for a public exhibition exploring this particular kind of cultural heritage, and used in the operetta A Night in Venice by the Kortrijks Lyrisch Toneel. It was then adopted as set dressing for the awards ceremony for the Flemish Culture Prizes.

Meanwhile, plans to restore some of the Dubosq sets last year had to be put on hold because of the pandemic, but the Asiatic forest set from Lakmé will be exhibited unrestored this summer for the Kortrijk City Festival Paradise. At the same time Forment will publish Droomlanders: Vergeten tovenaars van het geschilderde toneeldecor (Dreamlanders: Wizards of the painted theatre scenery), a history of theatre scenery designers in the Low Countries, aimed at the general public.

Research project

Increasing awareness of the cultural significance of the Dubosq collection prompted CEMPER, the Centre for Music and Performance Heritage, to ask Forment to lead a research project looking for other historic theatre scenery across Flanders. His findings, published at the end of 2019, highlighted small but significant collections at theatres in Leuven (now given to Kortrijk for safekeeping), Bruges and Lier, along with material originating from other theatrical traditions.

Some of the stage sets donated by Leuven to Kortrijk

Some of the stage sets donated by Leuven to Kortrijk© Johan Van Vooren

One of the most interesting had its origins in the Van den Berghe travelling theatre, a family business that put on popular plays around Flanders at the turn of the 19th Century. The company made its own scenery, gradually building up an extensive repertoire of interiors and exteriors, including Flemish locales such as the Rozenhoedkaai in Bruges. The artistic quality of these sets varied considerably. Some of the backcloths were finely detailed and relatively sophisticated in their use of colour, shade and perspective. Others were cruder, with clashing colours and little depth, producing a less convincing illusion.

When the head of the family died in 1928, two of his sons bought a hotel in Scherpenheuvel, a pilgrimage town in Flemish Brabant, and put on performances there. From 1931 onwards they also rented out the sets, costumes and props to other companies, making it a heritage not just of the travelling theatre, but also of local and amateur productions across Flanders.

Like the Dubosq sets in Kortrijk, the Van den Berghe sets survived because they continued to be used, and because the family continued to value them. But the collection was also divided over time between different branches of the family, and in some cases passed into other hands.

Circus Ronaldo

The largest collection remains with a branch of the family, Circus Ronaldo, which still uses them occasionally in performances. It has 175 rolled canvases, 101 painted on both sides for ease of transport, which can be assembled into 33 complete sets.

Also still in use are the five Van den Berghe sets owned by theatre researcher Chris Van Goethem. He rescued these when a Turnhout theatre company felt compelled to discard them, for fear they contained lead paint. He later offered a home to sets from the Zaal De Vrede theatre in Berchem, ordered out by the fire brigade, and these turned out to be from another branch of the Van den Berghe family.

Albert Dubosq: part of the Italian-Spanish public square, 1921

Albert Dubosq: part of the Italian-Spanish public square, 1921© City of Kortrijk

Meanwhile, a new life is beginning for another part of the Van den Berghe heritage, owned until recently by the Josée Nicola Ballet Studio in Beringen. These 31 sets, in exceptional condition, were sold in 2020 to Jed Wentz, an academic at Leiden University in the Netherlands who specialises in historical performance practices. His aim is to find a permanent home for the sets, ideally a theatre space where they can be combined with authentic lighting in performances that would both inform research and open them up to a broader public. The sets are also likely to be used in future editions of the Utrecht Early Music Festival, where Wentz is the artistic adviser.

The CEMPER research project probably unearthed all of the historic scenery in Flemish city theatres and specialist depots, but there may still be surprises. Van Goethem recalls being contacted by a cultural centre with some unknown scenery it had inherited from an amateur theatre group. On closer inspection, it turned out to be from La Monnaie opera house in Brussels, which was happy to have some of its lost heritage returned.

‘In a lot of cases you don’t just throw things away, you give them to an amateur theatre group, and they keep it,’ he says. ‘So if we go into the storage spaces of amateur theatre groups, I think we might still find more.’