Fiona Tan Looks at How We Look at Museum MAC’s

With Shadow Archive, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MAC’s) in Le Grand-Hornu presents Fiona Tan’s first solo exhibition in Belgium, in which the well-known Dutch artist shows her fascination for the way in which Western culture both archives and visualizes the world to gain control.

Born in Indonesia and raised in Australia, Fiona Tan is one of the Low Countries’ most internationally oriented artists: her work has been exhibited to acclaim all over the world, from Yokohama, via Berlin and the documenta in Kassel to New York and São Paulo. In 2009, she represented the Netherlands at the Venice Biennale.

Fiona Tan

Fiona Tan“I look at how we look,” is how Tan sums up her oeuvre, which comprises photos, film, and video. The year 1999 saw her first collaboration with an image archive: that of the Nederlands Filmmuseum (NFM, now part of the EYE Film Institute Netherlands) in Amsterdam. Using ethnographic films from the beginning of the twentieth century – then labelled as “primitive” – to investigate how we used to look at other peoples, the resulting video from this project, Face Forward, was noticed by Denis Gielen, the director of the MAC’s, which eventually led to this solo exhibition.

Fiona Tan, Facing Forward, still

Fiona Tan, Facing Forward, still© Fiona Tan / Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Shadow Archive presents two pre-existing large-scale video installations, Depot (2015) and Inventory (2012), but Tan has also created two new works that fully reflect the museum site and surrounding environment: the circular architecture of the former mining complex obviously provided natural inspiration.

The two older works form the opening section of the show. Depot (2015) consists of beautiful images from the natural history and science museums in Leiden and Berlin, from which Tan has selected all kinds of images of fluid-preserved specimens. It is an exquisite and colourful review of the victims of the Western urge to classify matter – preferably deceased.

Fiona Tan, Depot, HD installation, 2015, still

Fiona Tan, Depot, HD installation, 2015, still© Fiona Tan and Frith Street Gallery, London / photo Philippe de Goubert

The bizarre aspects of collecting are also highlighted in Inventory (2012), a video installation that evokes the interior of Sir John Soane’s Museum in London on six screens simultaneously. It is a beautiful work, but in this case real life surpasses the video registration. Soane, a late eighteenth- to early nineteenth-century neoclassical architect, stacked his house – which later became the museum – so full of fragments of and details from classical architecture that today there is hardly room for visitors to fit in the labyrinthic space.

Fiona Tan, Inventory, HD and video installatie 2012

Fiona Tan, Inventory, HD and video installatie 2012© Fiona Tan and Frith Street Gallery, London / Foto Philippe de Goubert

In a brand-new installation, Circular Ruins (2019), Tan plays on the former use of Le Grand-Hornu as a coal mine, when miners’ clothes would be hung up on cable pulleys both before and after work. In a similar fashion, Tan has suspended a number of large concentric circles that reference the building’s circular design, from which hang loose cords. A series of knots in each cord refer to the cord alphabet of the ancient Incas, while an excerpt can be heard from the short story “The Circular Ruins” by Jorge Luís Borges.

Fiona Tan, Circular Ruins, installation, 2019

Fiona Tan, Circular Ruins, installation, 2019© Fiona Tan and Frith Street Gallery, London / photo Philippe de Goubert

Even more intriguing is the other new installation, Archive (2019), which is entirely devoted to the Mundaneum, the museum and archive of Paul Otlet (1868-1944), the son of a Brussels tramway tycoon. As a reaction against the capitalism of his father, Otlet embarked on a pacifist world tour and endeavoured to realize a universal system of documentation. His magnum opus, in collaboration with Henri La Fontaine, was the Mundaneum or World Palace (Palais Mondial), which would contain all of human knowledge that was collected and classified.

To make such a comprehensive archive workable, Otlet introduced the Universal Decimal Classification or UDC code, which is still used in libraries and archive repositories today. However, while his paper archive is often regarded as a precursor to the internet, this idea is not entirely accurate: Otlet’s system was based on an extremely centralised concept of knowledge, whereas the internet is extremely decentralised, owing to its military background.

But the Mundaneum also had a spiritual purpose. The building that Otlet wanted Le Corbusier to build on Antwerp’s left bank was conceived as a pyramid with a funnel on top: inside, one open space, the sacrarium, would assemble all knowledge and all religions together in spiritual unity.

Collecting alle knowledge

In the exhibition Fiona Tan makes the obvious link between Otlet and the internet, referring even to Facebook and Google in the catalogue, companies which today are not seen in as favourable a light. But she also introduces a less well-known figure: Giordano Bruno, whose earlier, sixteenth-century project to collect all knowledge in one circular diagram led to his fate at the stake.

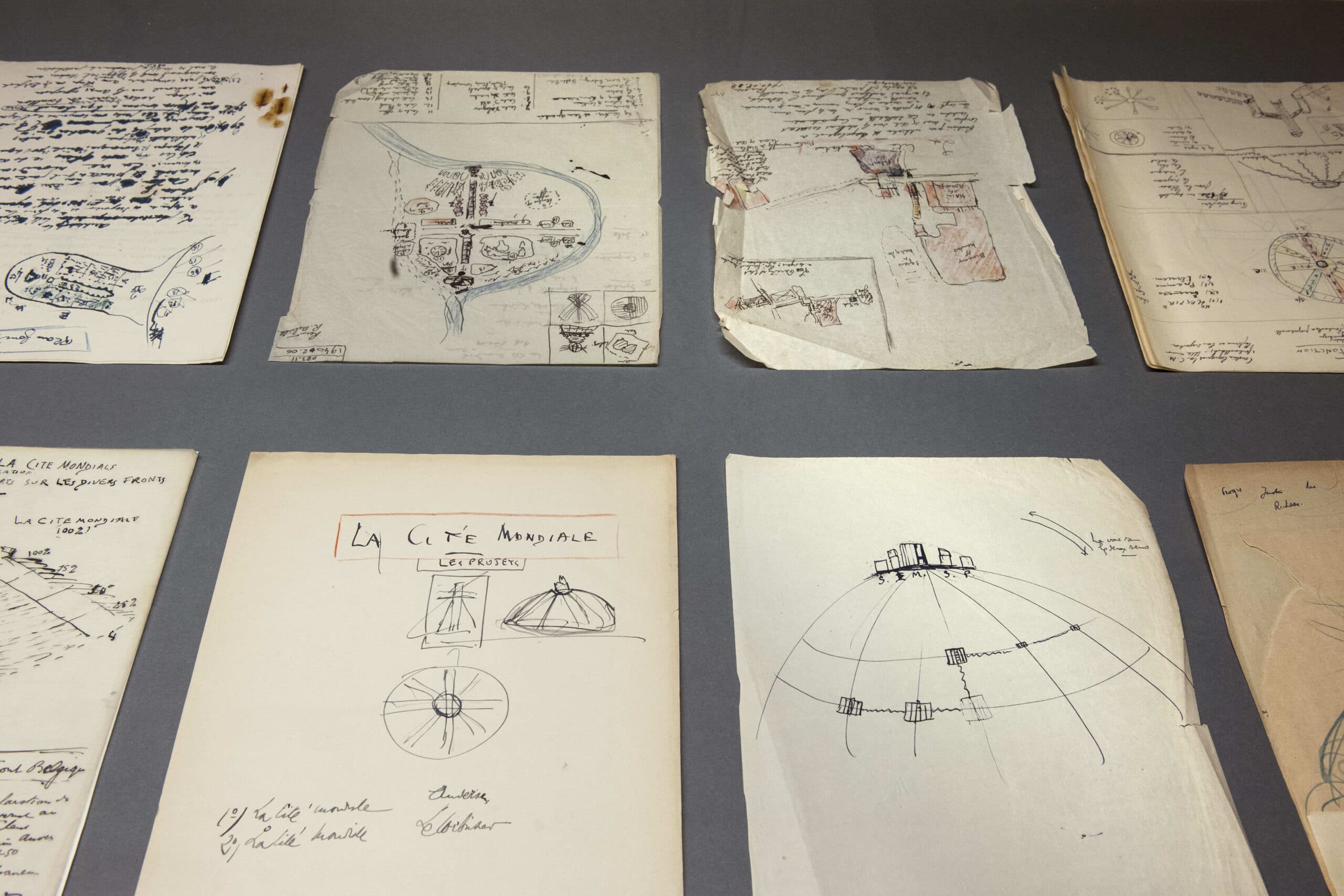

In a beautiful black and white 3-D animation film and stills – which could easily be mistaken for old photographs – Tan imagines a virtual reconstruction of the Mundaneum as a curved, shadowy space full of filing cabinets, devoid of human presence. The video is supplemented by an installation of display cabinets full of visionary drawings and handwritten notes in which Otlet refined the utopian project of his universal knowledge centre.

Fiona Tan, Circular Ruins, video, 2019

Fiona Tan, Circular Ruins, video, 2019© Fiona Tan and Frith Street Gallery, London / photo Philippe de Goubert

These four installations clearly show Tan’s fascination with the way in which Western culture archives and visualizes the world in order to control it, with Paul Otlet’s Mundaneum as the most utopian attempt, and one that also ended in bankruptcy. In 1934, the collections of the Mundaneum were banned from the Brussels Cinquantenaire or Triumphal Arch, where they had been located in a side wing (which today houses Autoworld). Later, the German occupier destroyed a large number of documents. Those that survived eventually ended up, in 1993, in the Walloon city of Bergen, where they are now being kept (with Google’s backing).

Drawings and notes from the Mundaneum by Paul Otlet

Drawings and notes from the Mundaneum by Paul Otlet© MAC's

Fiona Tan is certainly not the only contemporary artist to be interested in archives and museums. But her Shadow Archive is – partly because its site-specificity – one of the most beautiful approaches to the theme that I know. The exhibition does not present a historical overview but it is a perfectly selected series of works on the theme of the archive and how it has come to dominate our way of life. In the exhibition catalogue, Tan recounts an anecdote about the old Otlet, out walking with his grandson on the beach in Ostend. The child found a dead jellyfish; Otlet promptly pulled out a note, wrote the corresponding UDC code on it and stuck it on the animal.