Flemish Female Spies Watching Maximilian’s Every Move

Mata Hari and Edith Cavell were not, in fact, the first, trailblazing female spies in the Low Countries. According to archival documents, they were simply following in the footsteps of some illustrious women in the late Middle Ages who were enlisted as messengers and spies to support the Flemish states in a revolt against the Habsburgs.

Josine Hellebout, from Ypres, was unremarkable and unknown in her daily life. This, however, turned out to be an advantage since Josine, who lived in the second half of the fifteenth century, was a spy. She operated behind enemy lines during the war waged by the Austrian archduke (and later emperor) Maximilian against an alliance of Flemish and Brabantine cities fed up with interference from, and especially the taxes demanded by, the Habsburgs.

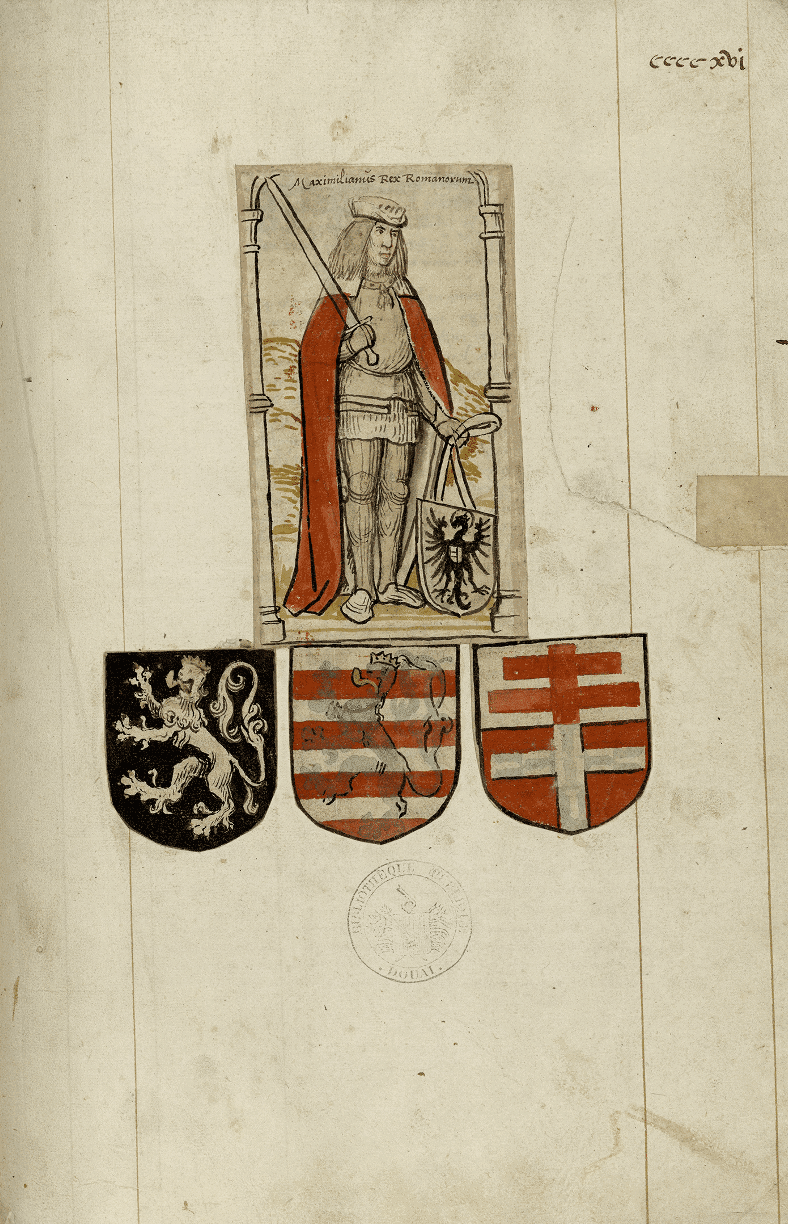

Miniature of Maximilian of Austria with coats of arms of the three rebel cities, Ghent, Bruges and Ypres.

Miniature of Maximilian of Austria with coats of arms of the three rebel cities, Ghent, Bruges and Ypres.© Douai, Bibliothèque Municipale, 1110, 416r

Hellebout carried out no fewer than eleven undercover operations during the Flemish revolt (June 1488 – October 1489). In the summer of 1489, she gathered intelligence about the Austrian troops stationed in places such as Diksmuide and Poperinge. We know this because the Ypres city accounts record that her job was ‘om maren te vernemene van de vianden’ (to gather information about the enemy). There is also a record of how much she was paid for her services: about eleven shillings per mission, or almost half a month’s wages for a well-trained craftsman of the time.

Hellebout was not the only woman to spy on Maximilian’s troops on behalf of her city. During the revolt, the recalcitrant Flemish and Brabant cities called on an entire army of female agents to spy on the enemy, keep track of troop movements, and deliver secret correspondence between the united cities. The tantalising story of these women was discovered by historians Lisa Demets (UGent) and Jelle Haemers (KU Leuven). Their study, which appeared in the online edition of the Magazine for History, shows that Flemish cities systematically employed women as spies not only during the Flemish revolt, but probably also during other conflicts.

Historians Demets and Haemers were able to find accounts relating to more than a hundred female spies or messengers

That women were active in military intelligence work in the Middle Ages can be classified as a historical discovery. Though there has already been some discussion of female spies in domestic and foreign specialist literature about the late Middle Ages in Europe, the accounts are both sporadic and isolated; and sometimes almost anecdotal. In the archives of the Flemish cities of Bruges, Ghent, Ypres and Kortrijk and the Brabantine cities of Brussels, Leuven and Nivelles, Demets and Haemers were able to find accounts relating to more than a hundred female spies or messengers.

The Camp of Charles the Bold at the Siege of Neuss in 1475, Adriaen van den Houte (1562)

The Camp of Charles the Bold at the Siege of Neuss in 1475, Adriaen van den Houte (1562)© Museum Hof van Busleyden, Mechelen /Joris Luyten

Perhaps it is not surprising that Ghent, with more than eighty women on the city’s payroll at the time, has received the most attention. It was, after all, one of the largest European cities of that era and certainly one of the most rebellious when it came to outside interference.

According to the Ghent archives, women from the city delivered hundreds of letters between Ghent and Brussels throughout nearly eighteen months of war. Although the majority of the letter carriers were male, women nonetheless accounted for a quarter of the correspondence between the two cities, the purpose of which was to collect as much information as possible about the enemy and then outsmart the Imperial forces through coordinated actions.

A prime example of this is the intervention that foiled the Austrian siege of Ghent in June and July 1488. The Ghent archive shows that on 4 June the city paid a woman (anonymous this time) for news from Dendermonde, where Maximilian had crossed the Scheldt. On 11 July, Magriete van den Driessche and Katheline Goorijs were compensated for their infiltration of the Habsburg army.

Detail of 'The Camp of Charles the Bold at the Siege of Neuss in 1475', by Adriaen van den Houte. On the right are army tents, on the left men and women serving soldiers inside and outside the ramparts.

Detail of 'The Camp of Charles the Bold at the Siege of Neuss in 1475', by Adriaen van den Houte. On the right are army tents, on the left men and women serving soldiers inside and outside the ramparts.© Museum Hof van Busleyden, Mechelen /Joris Luyten

During the siege, eight women and two men were paid wages by the city of Ghent for espionage. It was money well spent because the besieged city learned that the Habsburgs were suffering from food shortages, especially bread and meat, and were dependent on collaborationist Antwerp for their supplies. The army of Ghent was able to disable that lifeline with a targeted attack, after which the starving Austrians gave up.

Who were these Flemish spies, and how did they infiltrate enemy lines? We know their names, but the trail usually ends there. The fact that a man’s name is also often mentioned in the city accounts shows that many were married. ‘They were probably women from the urban middle class of the time,’ says Haemers. ‘They may have been the wives of merchants. In any case, they were women with a certain degree of wealth and education.’ That also explains why they received the same wages as their male colleagues.

Jelle Haemers (KU Leuven): 'The spies were women with a certain degree of wealth and education’

The women were able to mingle with the enemy by pretending to be travelling merchants or even pilgrims. Perhaps they posed as prostitutes. Paintings from that time often show women flirting with soldiers but, in truth, it is not very likely that the Flemish cities would have trusted prostitutes with tasks of military importance.

This evidence showing that many women were involved in intelligence work in late medieval Flanders will hopefully encourage other historians to look for the mention of women like Josine Hellebout in other conflicts and countries as well. How exceptional was she? Is it simply a fluke that evidence about her was discovered? Maybe. Maybe not. Finding written records could, however, be quite a challenge. After all, Maximilian was victorious in the end and the first thing a besieged city does when the enemy takes over is to destroy any sensitive documentation.

This article previously appeared in De Standaard

newspaper.