For 400 Years Now, a Little Peeing Boy Stands for the Subversive Spirit of Brussels

Manneken Pis, the most famous inhabitant of Brussels, celebrates his 400th birthday. Although its origins are older, the bronze statue of the peeing boy as we know it today was made in 1619. With a mere 58 cm, Manneken Pis has grown from a fountain into the symbol of Brussels, known throughout the world. The little boy incarnates the carelessness of the inhabitants, but also their resistance.

As you arrive in Brussels you see the town hall tower from afar. From afar you see the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, its copper-green dome, the spheres of the Atomium, which have been cleaned up again. The Palais de Justice, with its golden dome and worn-out mantle of scaffolding, are visible from all around.

But the most famous monument in Brussels is one you only see when you stand right in front of it. A little chap in bronze. A menneke, as we locals say; manneken to the outside world. You do not need to search for it either; just follow the stream of tourists around the Grand Place. Be ready to turn down narrow alleyways. Do not be surprised if you see it before you reach your destination. Rows, regiments, cohorts, legions of mannekens adorn the shop windows along the path to the one true manneken. Manneken bottle stoppers, manneken corkscrews, mannekens painted onto jugs, tankards, mugs and cups of various sizes, manneken beermats, manneken fridge magnets and lots, lots more. I suspect that somewhere in China, in a small town with a couple of million residents, the entire population manufactures mannekens in all conceivable shapes and sizes from morning until night, to the delight of foreign visitors, many of them also Chinese, who grace the capital of Europe with their presence, and to the benefit of the local tradespeople.

Manneken Pis merchandise

Manneken Pis merchandise© Dimitris Kamaras/Flickr CC

Everyone in Brussels is fake

Did I just write ‘the one true manneken’? Nonsense! Firstly, it’s not unique. A little further on you will find Jeanneke Pis, then outside Brussels in Zelzate there is Mietje Stroel. Genuine mannekens can be found in Geraardsbergen, Poitiers, Colmar, Osaka, Botafogo near Rio de Janeiro, and Cuernavaca in Mexico.

Jeanneke Pis

Jeanneke Pis© Flickr/su-lin

In Lacaune, in the Tarn, France, the fountain is named ‘dels Pissaïres’, and boasts four gentlemen. There is even one in Algeria. The United States, however, will not grant him entry. A waffle maker from Orlando, Florida, thought his Belgian product would sell better if he erected a manneken in front of his shop. Passers-by, however, were shocked and complained; yes, that’s how it goes in the United States. The waffle maker was obliged to remove the statue. I await with considerable anticipation the moment when some sensible soul on Facebook might start a campaign against the manneken for its political incorrectness.

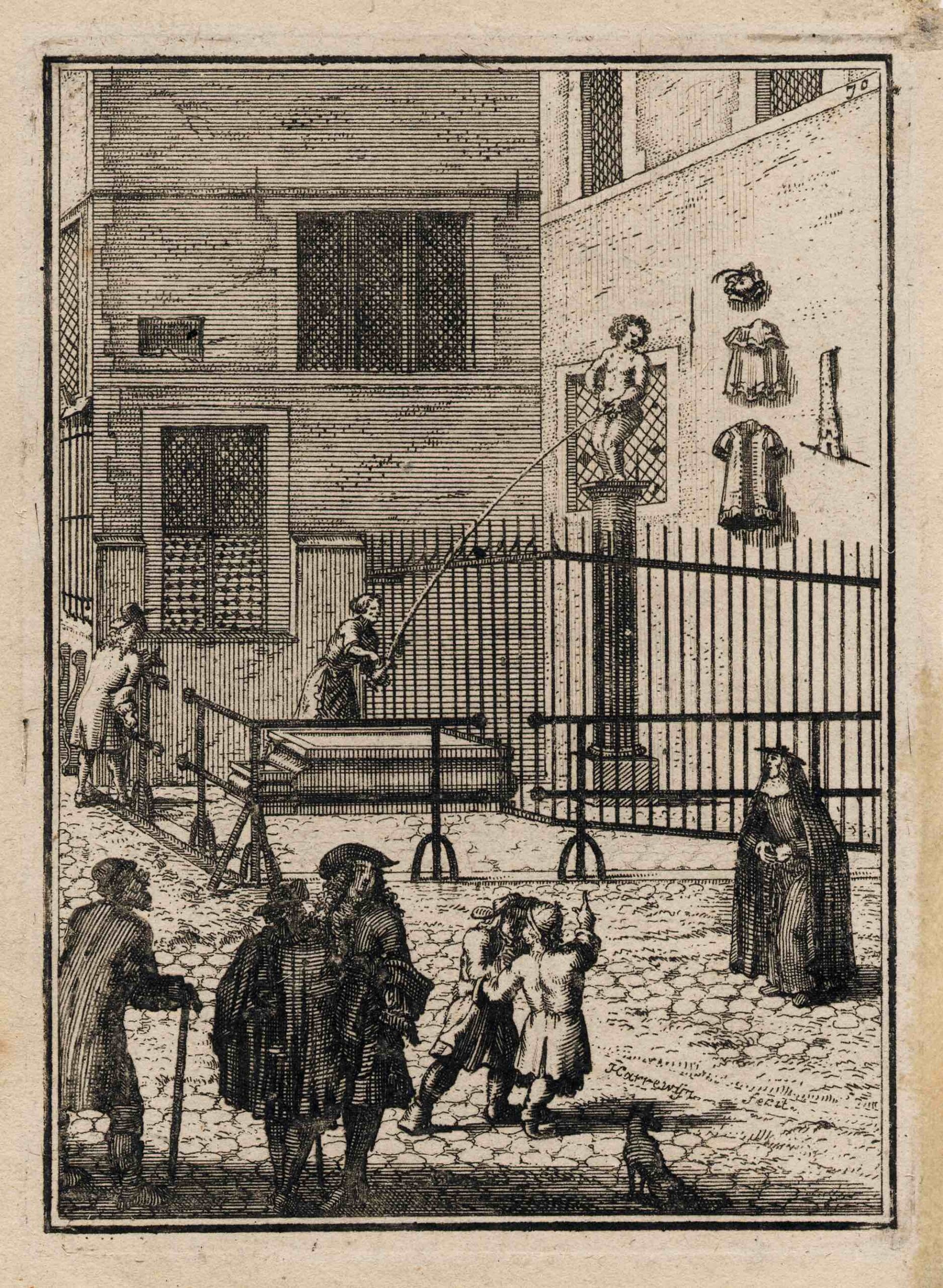

The oldest known picture of the fountain, early 18th century

The oldest known picture of the fountain, early 18th century© City of Brussels Museum

Secondly, it is not the genuine article. Brussels’ oldest citizen is not an original, but that is no problem around here. We have pretty flexible ideas about who counts as a true local. The solution we have found is obvious: everyone does. The reason is equally obvious: more or less everyone in our city is fake.

In the course of history the statue has been stolen and damaged a number of times. In 1965 vandals broke it in two, leaving only the feet and ankles standing. The culprits were never found, but the remains of the statue were recovered, restored and put on show in the Broodhuis, the Museum of the City of Brussels. The Compagnie des Bronzes of Ransfortstraat in Molenbeek was commissioned to make two new casts, which resemble the original like peas in a pod, and one of which has adorned the fountain ever since. The Compagnie closed its doors in 1979, having cast countless statues, including Jan Breydel and Pieter de Coninck in Bruges, the craftsmen on the Kleine Zavel square and the Brabo fountain in Antwerp. The site now houses the Museum of Industry and Work, and the street may see the occasional passing jihadist from time to time.

Gushing fountains

In fact this is really a tale of water pipes. The earliest documents tell us that around 1450 a ‘menneke pist’ (little man urinates) on the corner of Stoofstraat and Eikstraat. That menneke was a stone statue.

Around a century earlier, Brussels’ leaders had had three underground pipes made to feed the city’s fountains. To avoid confusion among pedants, by city I do not mean the area covered today; only its pentagonal core, the area situated within what is currently called the small ring, which largely follows the line where the second city wall once stood.

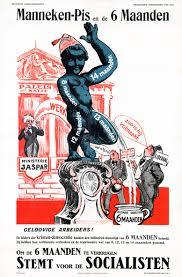

Manneken Pis embedded by the Belgian Socialist Party in the elections of 1929.

Manneken Pis embedded by the Belgian Socialist Party in the elections of 1929.© City of Brussels Museum

Most housewives hauled buckets and pitchers daily to the nearest public fountain to supply their families. Those fountains were monumental. The greatest number were found in the neighbourhood of the Nedermerct, today’s Grand Place. Brussels is a hilly city. The water was piped from high to low points via reservoirs and associated buildings. One of those, beautifully named ‘De Grote Pollepel’ (the big ladle), was situated halfway up a slope, where the Ravenstein Gallery is now. When the gallery was built De Grote Pollepel was moved to the park behind Egmont Palace, but the ladle only catches rainwater now. Egmont Park is not well known, as it is only accessible from three narrow alleys, one on Wolstraat, one on Waterloolaan and one on Grote Hertstraat.

The pissing child was far from the only fountain. On today’s Priemstraat, for example, the Juliaenekensborre spouted drinking water; on the Grand Place itself there was a spectacular model with as many as five basins; there was even a fountain with three women apparently spouting water by pinching their nipples. Sadly nothing remains of these. That does not mean, though, that the Lower Town is now otherwise devoid of fountains. Look for De Spuwer, for instance, behind the town hall, or take a peek at the courtyard of the town hall, where the Maas and Scheldt fountains flow.

Pissing on the helmets of the enemy

The peeing child would inevitably become the hero of many a tale. The stories even refer to times long before the first statue existed. In the eighth century, the father of a baby was said to have threatened the virtue of a beautiful noblewoman, later known as Saint Gudula. She chased her assailant away with a double curse: ‘Your only son will never grow again and will continue to urinate for eternity!’

Other stories mention a child urinating against a witch’s door and immediately turning to stone or a little chap suffering a call of nature during a procession of crusaders and finding himself unable to stop, or a little guy who, when Brussels was under siege, pissed on the burning fuse of a keg of gunpowder.

Battle of Ransbeek, now Neder-Over-Heembeek (middle 12th century). The people of Brussels had brought the duke along in his cradle, which they hung on the branch of a tree (see on the left). The infant stood up and pissed over the edge of his hanging bed, right onto the helmets of the advancing enemy.

Battle of Ransbeek, now Neder-Over-Heembeek (middle 12th century). The people of Brussels had brought the duke along in his cradle, which they hung on the branch of a tree (see on the left). The infant stood up and pissed over the edge of his hanging bed, right onto the helmets of the advancing enemy.© City of Brussels Museum

Perhaps the best story is as follows. Around the middle of the twelfth century, a new duke took office in Brabant at the tender age of two. In those days, parents were in the habit of dying at inconvenient moments. The arch-enemies of the child duke saw their chance and attacked Brussels with all their might. There was a confrontation in Ransbeek, now Neder-Over-Heembeek, the northernmost corner of Brussels. The people of Brussels, however, had brought the duke along in his cradle, which they hung on the branch of a tree. The infant stood up, stark naked, and pissed over the edge of his hanging bed, right onto the helmets of the advancing enemy. Panic broke out. The people of Brussels made mincemeat of their besiegers.

There was indeed a Duke of Brabant, Godfried III, who bore the nickname ‘dux in cunis’, the duke in the cradle. But cradle or not, the historical truth is of minor significance in this kind of story. In my view this tale is the most uniquely Brussels of them all. Episodes such as the one with Saint Gudula or the witch can be found in countless variants all over the world, but a naked child chasing away soldiers by pissing on their helmets is something completely different.

Manneken Pis dressed up as Elvis Presley © City of Brussels Museum

Manneken Pis dressed up as Elvis Presley © City of Brussels Museum© City of Brussels Museum

The child wins against brute force. Now it might be argued that the motif of the weakling who is laughed down by everyone and wins against the mighty, the cruel, the bully or the giant, can equally be found in a great many languages and cultures. David and Goliath, Tom Thumb, the Brave Little Tailor; who does not know such stories? But this is about a single deed, or, to put it better, a single stream. The mighty are effortlessly humiliated, in the most natural manner humanly conceivable. David slung a stone. There is nothing natural about that. That is a story of guile and aggression. The stone is slung to kill the giant enemy or at least to injure him. The naked duke did nothing of the sort. Someone pissing is not committing an act of aggression. On the contrary, he makes himself quite vulnerable in the moment. Nevertheless he chases away men armed to the teeth, simply because the need arises, and it is a need we all share. There is something irreverent, something anarchistic, subversive, but also extremely human, about it. And thus something particularly characteristic of Brussels.

Smiling down at passers-by

We know that in the seventeenth century the people of Brussels were devoted to their manneken, and in his current form too.

In 1619 the city council in any case considered it worth the trouble and expense of commissioning a famous sculptor, Hieronymus Duquesnoy, to provide a new bronze statue for the fountain on Stoofstraat. Duquesnoy was one of the best, if not the very best, at his craft in the Spanish Netherlands and did not disappoint his commissioners. He produced a lively little chap, just over half a metre tall. The boy holds his winkle in his left hand, his little head bowed slightly to the left, smiling down at passers-by. He stands tall, the most base of figures elevated.

We jump ahead in history to 1695. On 13 August of that year, the army of the French King Louis XIV began to fire upon the city of Brussels from Scheut. Two days later the entire city centre was ablaze. One third of the built-up area was razed to the ground. There were very few victims, as the residents managed to flee to Koudenberg, where the governor’s palace was located. But first they evacuated their manneken to a safe place, such was the importance they attributed to the little statue. It was clearly held in higher regard than the other city fountains.

Just a couple of days after the barbaric bombardment the manneken returned triumphant to the smouldering ruins. A long satirical poem emerged in which the French are cursed for failing to let him get on with his wet work in peace and because their fireballs drove away his admirers.

Manneken Pis dressed up as Lawrence of Arabia

Manneken Pis dressed up as Lawrence of Arabia© City of Brussels Museum

Admirers

Over the ensuing centuries, their ranks swelled. In 1698 the governor of the Spanish Netherlands, Maximilian Emmanuel of Bavaria, presented the manneken with his first suit of clothing: Bavarian blue, with a hat far too big for the bronze child’s head. It was the beginning of a wardrobe which has now expanded to more than eight hundred items. Manneken Pis can dress up as Elvis Presley and Mozart, as a spaceman or a street sweeper, as Nelson Mandela, Obelix or an Anderlecht footballer; he has every conceivable costume, or so it would appear to the visitor, because for a good long time he has really just worn skilfully cut pieces of cloth, attached by Velcro.

Over time the manneken has gained all kinds of symbolic meanings. Mention was made of fertility and even Jesus Christ. Only one such meaning remains today. Manneken Pis is the symbol of Brussels, both the city and the region. The rest is fodder for history. The symbol of Brussels is a naked little lad pissing in public. People have been reported for less.

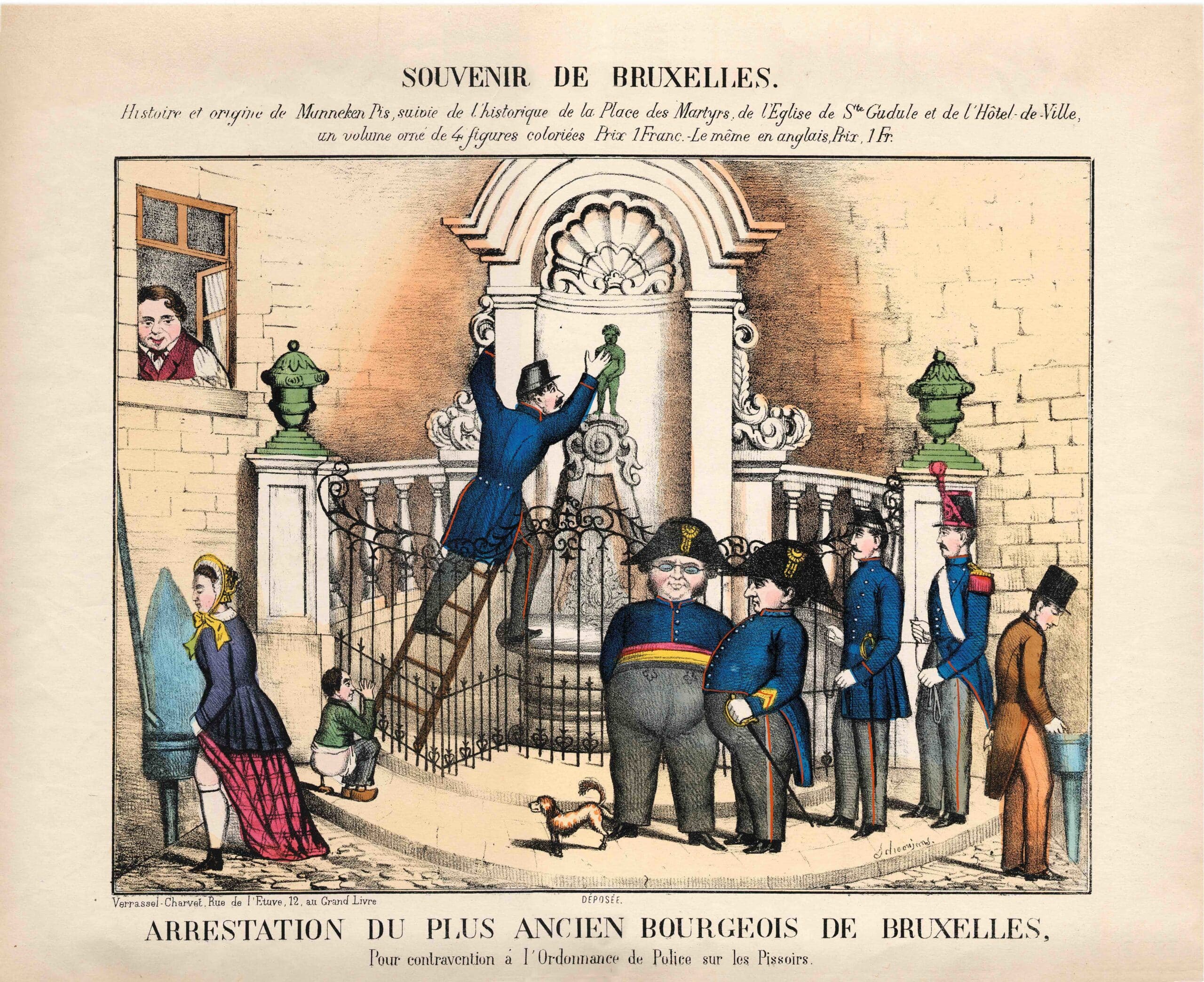

Government attempts at curbing public urination are not just a recent phenomenon. In Brussels they were trying to stamp it out more than a century and a half ago. There is a satirical drawing from 1846 which depicts a police officer up a ladder which he has placed against the railing in front of Manneken Pis. ‘Arresting the oldest citizen of Brussels ,’ the caption states.

Arresting the oldest citizen of Brussels, 1846

Arresting the oldest citizen of Brussels, 1846© City of Brussels Museum

Manneken Pis stands for the lightly satirical attitude with which the people of Brussels greet any form of authority. The little street child is as unconquerable as he is small. He may appear to be hidden away in a corner of an unprepossessing side street, but the entire world comes to see him.

He once stood in the capital of the Duchy of Brabant, initially only pissing on the heads of the people of Brussels, and perhaps by extension those of Brabant. He then stood in the capital of the Kingdom of Belgium and pissed on the heads of all Belgians. Now he stands in the capital of the European Union and pisses on the heads of half a billion Europeans. He remains the same, but his domain grows, so in relative terms, according to mathematical law, he becomes smaller. His irony grows proportionally and has now reached gigantic dimensions. He does not need to do anything other than engage in the double offence of standing naked where he has always stood and pissing in public. Mighty Europe is rendered impotent. The richest empire in the history of humanity is forced to put up with a pissing toddler as the prevailing symbol of its proud capital.

Many of the tourists parading past the fountain appear perplexed. Isn’t he a bit small? Look what a ridiculous little corner he’s standing in. For it is not only his public indecency which is subversive. He is an anti-monument par excellence. His half-metre stature satirises, lightly, perhaps, but no less mercilessly, the disingenuous glorification of all statues depicting scoundrels, whether they are crowned or not.

Such statues are always displayed on prominent squares or broad streets. The Place Bellecour in Lyon, adorned by an equestrian statue of Louis XIV, or Unter den Linden in Berlin with Frederick the Great, are shining examples. Our manneken does not even come up to the buttocks of a bronze horse like that. Those are just two examples out of dozens and dozens. In the centre of Skopje there is a statue of Alexander the Great twenty-eight times the size of our manneken, along with one of his father Philip twenty-six times larger. If Macedonia ever enters the Union the capital of Europe might perhaps send them two copies of the manneken to piss on their pedestals.

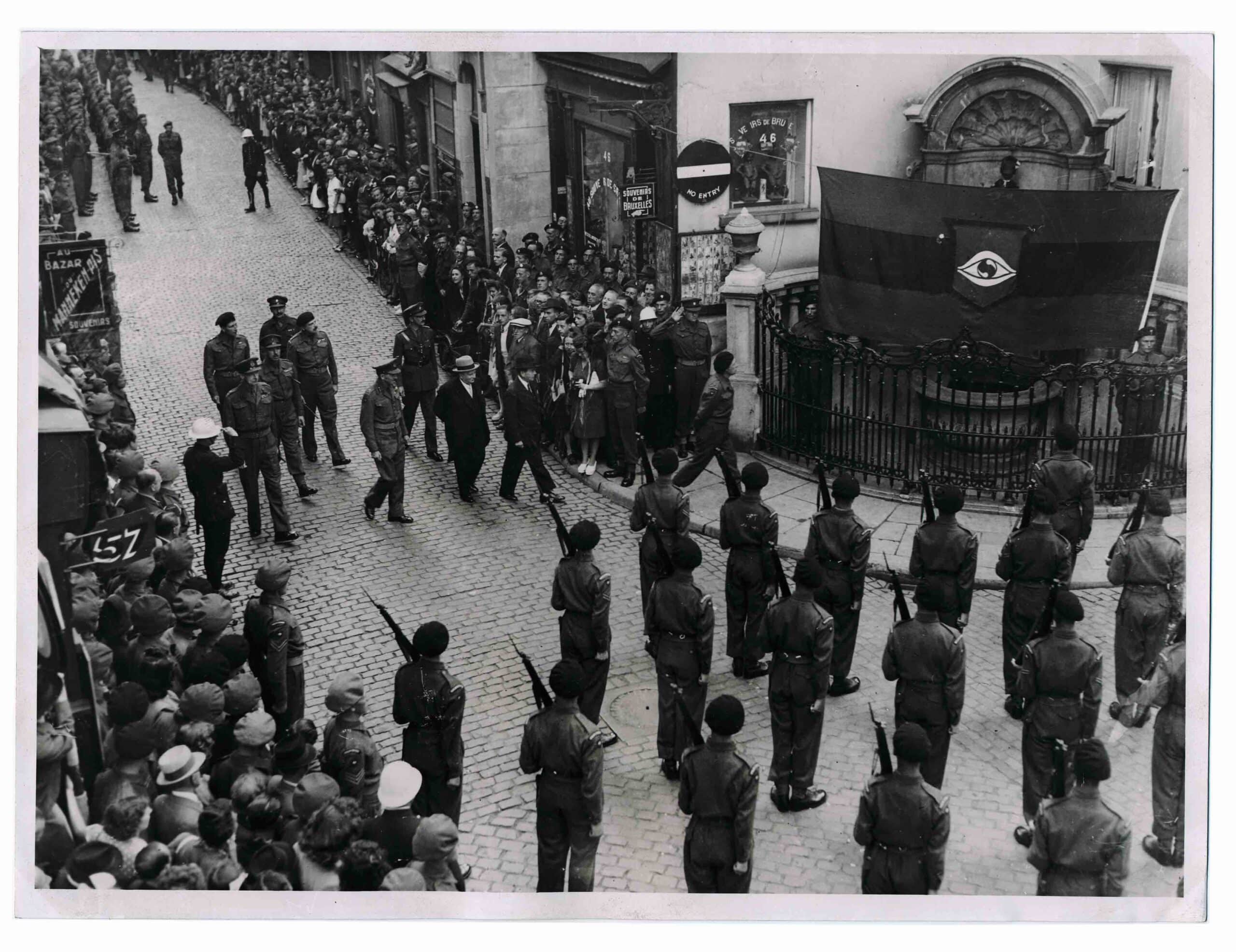

Ceremony for the official presentation of the costume of the Welsh Guard, 29th July 1945

Ceremony for the official presentation of the costume of the Welsh Guard, 29th July 1945© City of Brussels Museum

A little resistance to Europe's conceitedness

In all the self-mockery of Brussels, the anarchy (and of course the disagreeable tendency of the people of Brussels towards indifference), combined with the labyrinthine Belgian state structure, we have failed to note the explosiveness of it all and it has blown up in our faces. Brussels is not a failed city, nor Belgium a failed state – far from it – but it is high time we set our house in order. It is an urgent task of social responsibility and civilisation. But however necessary it may be, that work cannot be allowed to crush our sense of small-scale resistance, as stubborn as it is carefree. That is more precious than ever, especially now that cold technocracy, lacking any sense of harmless fun, penetrates ever deeper into our daily lives. A pissing toddler in a corner of the European capital – I cannot imagine a better remedy for Europe’s conceitedness.