How the First Dutch New Yorkers Interpreted the U.S. Constitution

In 1788, as New York fiercely debated the ratification of the United States Constitution, a Dutch Reformed minister quietly translated the founding document into Dutch. Despite its historical significance, this first Dutch translation remained virtually unknown for over two centuries, until historian Michael Douma researched it. The document offers a rare glimpse into how early Americans of Dutch descent understood their new nation’s laws.

I began studying the Dutch in America over 20 years ago, when I was a freshman at Hope College, and I never had much interest in Lincoln, Madison, or the Constitution. Rather, for years, I spent most of my time in the archives, looking at unread files, sometimes producing translations of old Dutch documents that might be useful for my research on Dutch American immigrants. My friends and colleagues knew me as the American who studied the Dutch, and any time that a question about the Dutch arose in their research, they would email me.

This is how, in 2012, Christina Mulligan, now a law professor at Brooklyn Law School, approached me to comment on a 1788 Dutch translation of the U.S. Constitution. At first, I assumed that other historians, particular legal scholars and historians of Dutch New York had thoroughly studied this document. But to my surprise, I found that this Dutch translation was almost entirely unknown and unexplored. Alongside a German translation produced around the same time, this Dutch translation of the U.S. Constitution provides a window into how early Americans might have understood the words of one of their founding documents.

The first Dutch translation of the U.S. Constitution was almost entirely unknown and unexplored

The U.S. Constitution was written and approved at a national convention in 1787. But before it could be legally accepted as the national law, it had to be “ratified”, that is, certified or accepted by 9 of the original 13 states. In 1787 and 1788, there were fierce political battles about ratification waged at the state level. New York ratified the Constitution on July 26, 1788, becoming the 11th state to do so. But this was superfluous, because a ninth state, New Hampshire, had already ratified the Constitution in June, 1788. The Dutch translation of the U.S. Constitution was produced in this factious political environment of 1788.

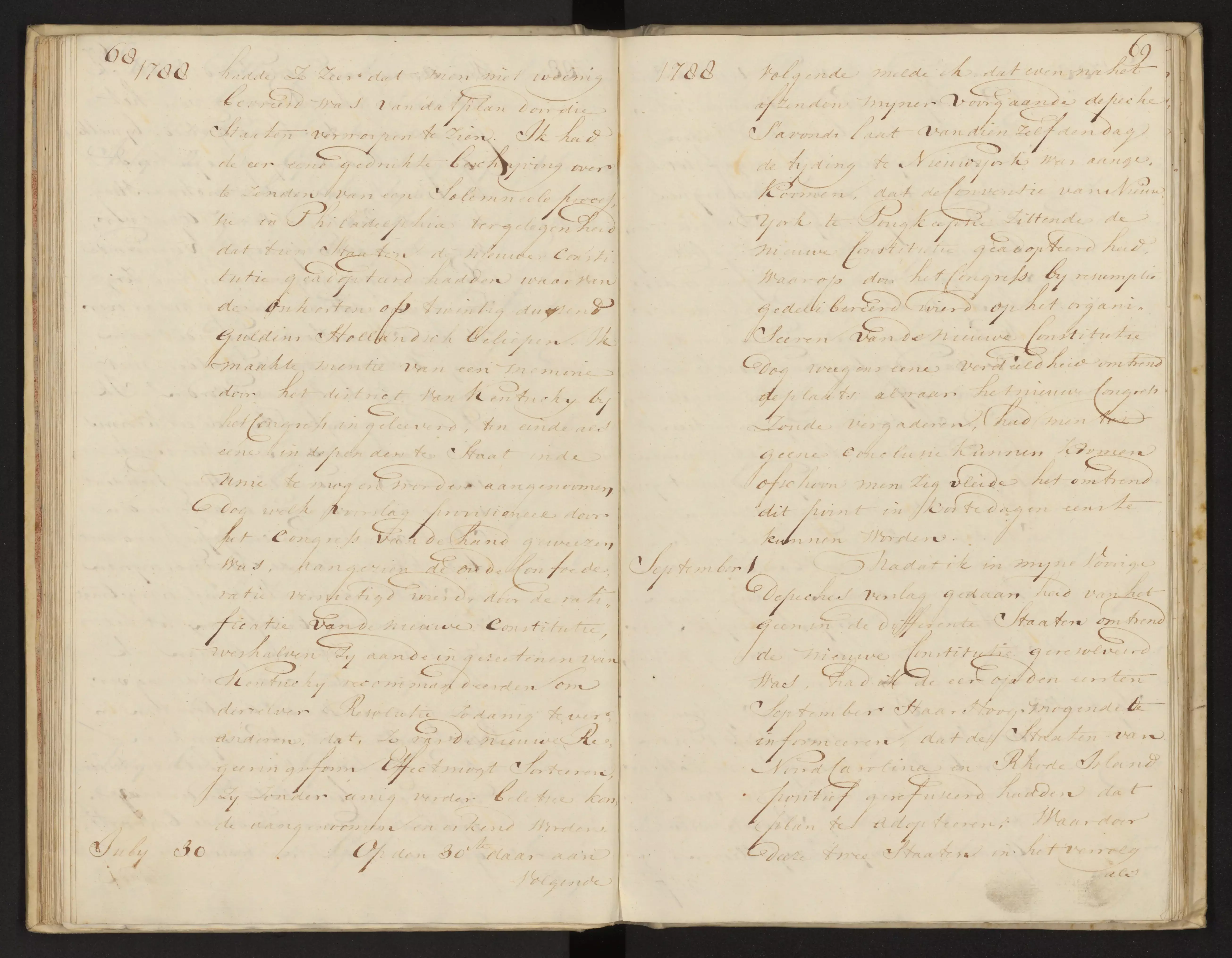

Note of the ratification of the Constitution by New York in the report of Dutch Ambassador Pieter Johan van Berckel, 30 July 1788

Note of the ratification of the Constitution by New York in the report of Dutch Ambassador Pieter Johan van Berckel, 30 July 1788© National Archives of the Netherlands

The translator was named Lambertus de Ronde, a Dutch Reformed minister living near Albany, New York. I began my reading of his translation by attempting a “reverse translation,” essentially trying to produce an English text of what I understood of De Ronde’s words. Through this method, I figured I could locate places in De Ronde’s text where his translation departed from the original language and from conventional understandings of the Constitution.

In addition, by working from De Ronde’s translation, without immediately consulting the original English version, I wouldn’t be biased by the original word choices of James Madison, et al. It was even to my benefit at the time that I wasn’t all that familiar with the text of the Constitution or the debates about its interpretation. I would work with fewer initial biases.

I discovered several places where De Ronde had peculiar interpretations of the text. For example, he seemed to interpret the Commerce Clause narrowly to refer to merchants, not common persons trading across state lines, and he interpreted the Progress Clause “for limited Times” as “voor bepaalde tyden”, that is a certain time, suggesting that it is a finite time. By placing the Dutch translation alongside the contemporary German translation and the English original, our team of scholars created the first tri-lingual, annotated version of the Constitution and its translations of 1788. Our article and associated appendix allow legal scholars to look more closely at particular sections of the text of that Constitution that they are interested in, and, potentially to tease out more meaning about how at least some early Americans interpreted this founding document.

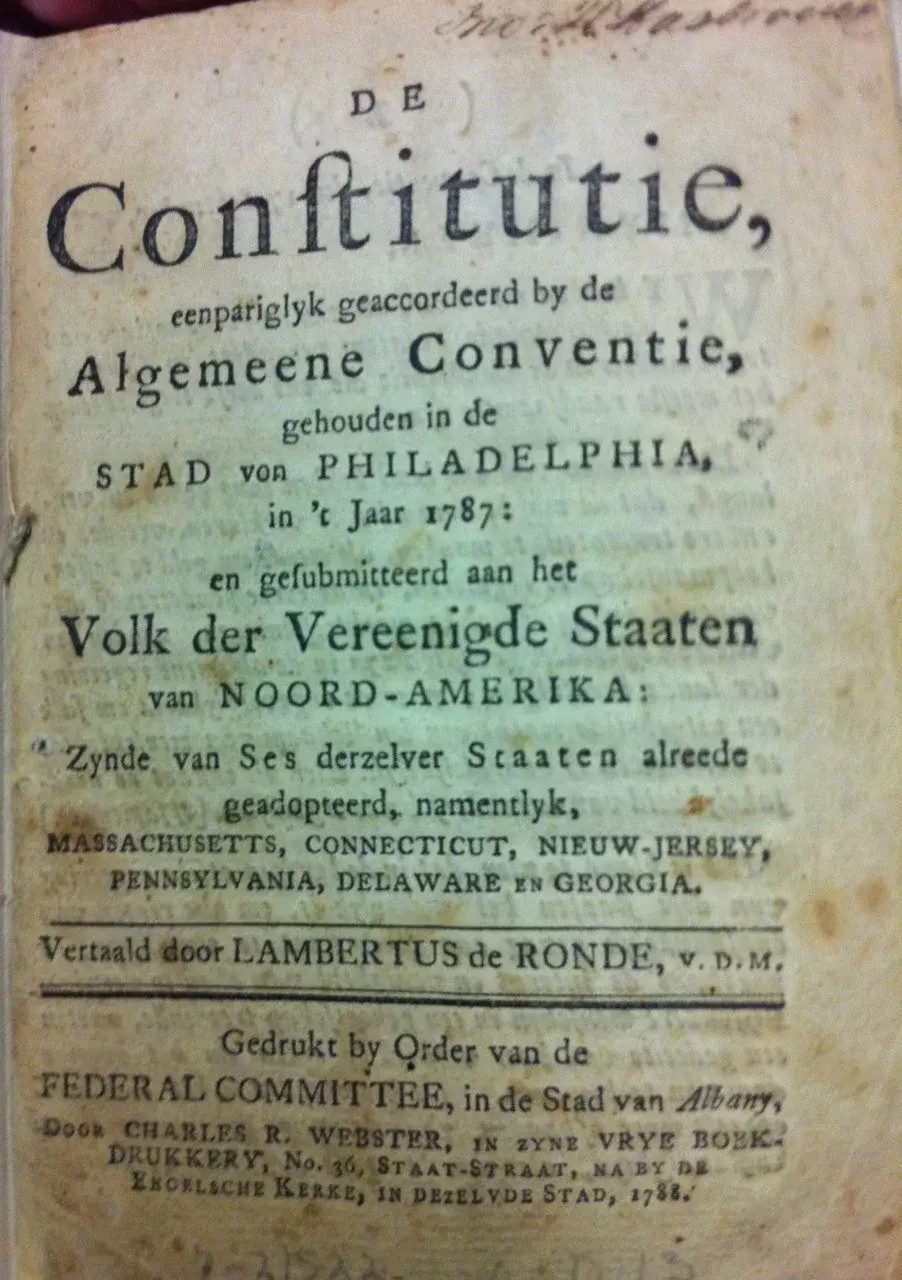

Title page of Lambertus de Ronde’s translation of the U.S. Constitution, 1788

Title page of Lambertus de Ronde’s translation of the U.S. Constitution, 1788© Library of Congress

Although the issues of legal interpretation will certainly have a broader audience, I am probably more interested in De Ronde’s translation as an artefact of late 18th-century Dutch New York culture. That is why I wrote and published a follow-up article that looked deeper into De Ronde’s background and placed his writing in an international context, specifically comparing it to a translation of the U.S. Constitution made in the Netherlands five years later, in 1793.

De Ronde faced a difficult task. He was educated as a minister in the 1740s, but many books he owned and read were from the 17th century. He was born in the Netherlands, but in coming to New York in the 1750s, he discovered a peculiar accented American Dutch language, with a host of new vocabulary and perhaps even some old-fashioned words that had since died out in patria.

Lambertus De Ronde discovered a peculiar accented American Dutch language, with a host of new vocabulary

De Ronde’s house in Manhattan was raided by the British in the Revolution, and he fled to the Hudson Valley. After the war, he protested his treatment during the war, and begged the Synod of the Dutch Reformed Church to reinstate him in his pulpit in Manhattan. But the church had different ideas, and in the 1780s, De Ronde became something of an itinerant minister, frequently plying up and down the Hudson River, giving good old orthodox sermons to congregations from Schagticoke to Saugerties.

In 1788, De Ronde was a respected elder minister with a command of written and spoken Dutch that must have been seen as authoritative to the Dutch-descent New Yorkers who now sent their children to schools taught in English. De Ronde struggled to learn English, and although he eventually learned it, he might not have ever written or spoken the language well. When he took on the task of translating the new constitution into Dutch, he must have felt that he could read the language well enough to explain it to his fellow Dutch New Yorkers.

There was clear political motivation in translating the Constitution into Dutch. The Albany Federalist Party supported De Ronde’s translation. To some extent, this was an appeal to the Dutch constituency in New York, which was divided into Federalist and Anti-Federalist camps. But I believe that this was also a sign that there were indeed a significant number of New Yorkers who could still read Dutch but not English, or at least they could read Dutch much more easily than English. In other words, I doubt that the Albany Federalist Party would think that a Dutch translation of the Constitution would be a useful symbolic exercise.

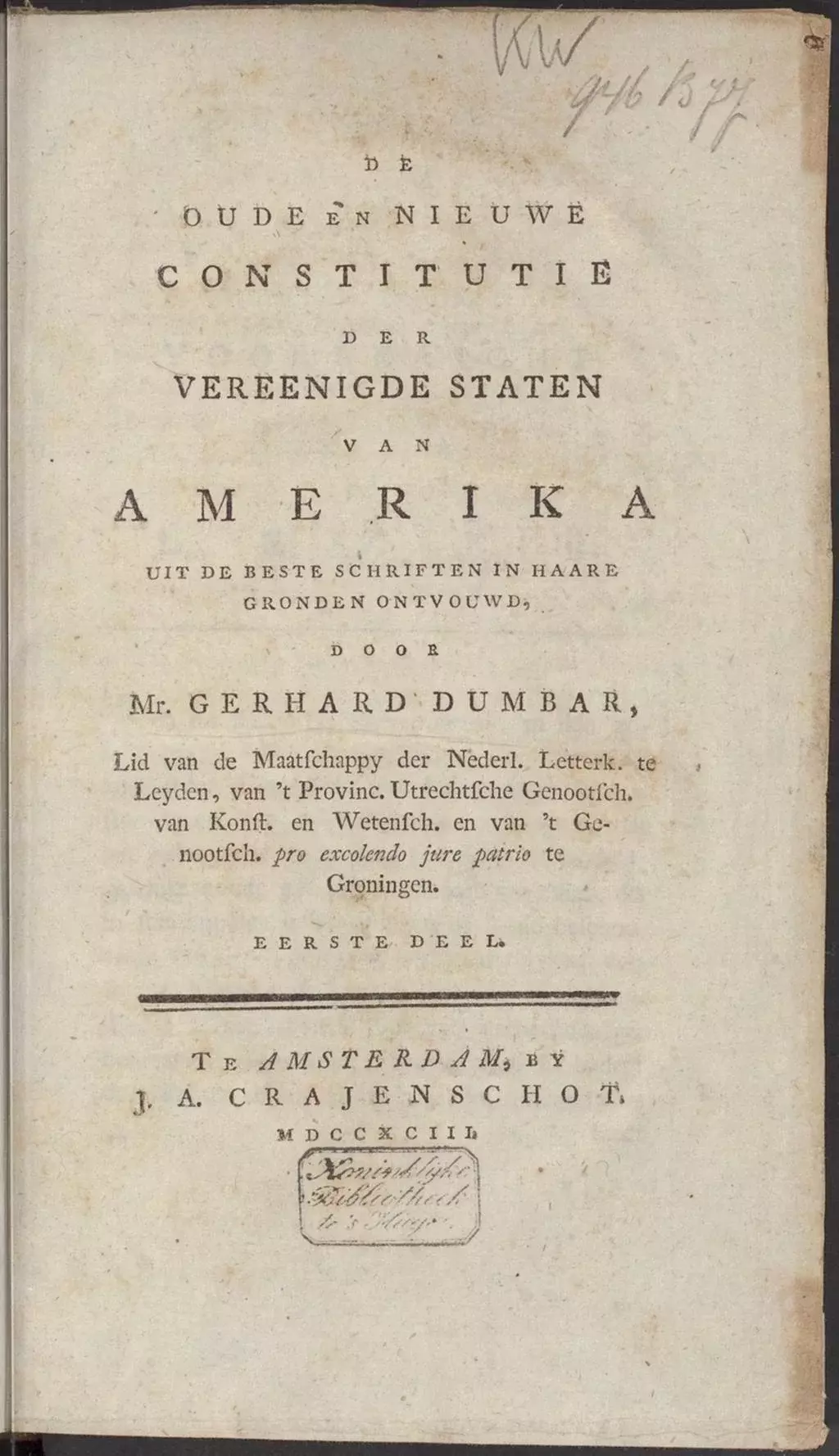

Title page of Dumbar’s book on the American Constitution, 1793

Title page of Dumbar’s book on the American Constitution, 1793© National Library of the Netherlands

At any rate, when De Ronde’s translation arrived in the Netherlands, the Dutch legal scholar Gerhard Dumbar was quick to call it “flawed in its execution.” Dumbar certainly felt that de Ronde had misunderstood legal and political terms and their context, but he might also have been put off by De Ronde’s colloquial New York Dutch and his frequent Americanisms that crept into the document. It is not clear, for example, if De Ronde understood much about “Republicanism” as an ideology, especially since he translated “republican” as “republieke”, and he gravitated to cognates whenever possible to adhere closely to the English original, sometimes when better Dutch words were available. De Ronde speaks of “de constitutie” instead of “de grondwet”, “representatives” instead of “vertegenwoordigers” , “taxen” instead of “belastingen.” Proper nouns like “President”, “Congress”, and “chief justice” keep their original form, as do “impeachments”, “indictment”, and “adjournment.”

De Ronde created a translation for common New Yorkers who spoke Dutch, while Dumbar created a translation aimed for lawyers and politicians in the Netherlands

A natural question arises when comparing De Ronde and Dumbar’s translations: whose translation was better and why? What is more, who is to say what it means to create a better translation? After all, that the two men had different interpretations doesn’t mean that one was right and the other was wrong.

De Ronde was shaped by the “oude schrijvers” of 17th century Dutch Calvinism. He learned English in America and was familiar with domestic political debates. Dumbar, however, was trained in law and legal history. He read modern politics and specialized in the study of federalism and republicanism. De Ronde created a translation for common New Yorkers who spoke Dutch, while Dumbar created a translation aimed at lawyers and politicians in the Netherlands. It is no surprise that they disagreed on word choice. Dumbar avoided all the cognates that De Ronde had used. For example, where De Ronde wrote “legislature” Dumbar used “wetgevende magt”; where De Ronde said “taxen” and “tollen”, Dumbar gave “belastingen, imposten.”

Despite a persistent myth, there is no evidence that the early United States considered Dutch or German as a national language

Naturally, some places in the constitution’s text require some understanding of legal history to understand properly. De Ronde was confused about what precisely a felony was. Dumbar, however, explains the term at length in a footnote to the text. Dumbar also added notes to explain things like “indictment”, “quorum”, “bill of attainder,” “militia”, and “habeas corpus.” On the other hand, De Ronde produced a translation devoid of footnotes. Organizations interested in the history of the Dutch in America have probably overlooked De Ronde and owe him some more interest.

Commemorative stamp on two hundred years of Dutch-American relations, 1982, designed by Gert Dumbar

Commemorative stamp on two hundred years of Dutch-American relations, 1982, designed by Gert Dumbar© National Archives of the Netherlands

Despite a persistent myth, there is no evidence that the early United States considered Dutch or German a national language, or one in which the constitution should be written. In Canada, by contrast, the national Constitution was written in both French and English. When Canadian legal scholars debate the meaning of their constitution, they can cite versions of the text in two languages. This can lead to clarity or confusion. The early Dutch and German translations of the U.S. Constitution cannot be cited as official documents of American governing principles, but perhaps they can shed light on the meaning of the English text of our most important founding document.

This article was originally published on the website of the National Archives of the Netherlands.