Artist-Activist Frans Wuytack: ‘Art Makes People Want to Live in Reality’

The Flemish artist and peace activist Frans Wuytack celebrated his ninetieth birthday with a festive retrospective and a book. Wuytack has led an eventful life: he was a worker, priest, rebel and sculptor. But his drive is still as fiery as ever, and he still hopes to live to see the ‘world revolution’. From his green home, the ‘paradise’ where he lives with his wife, Wuytack looks back on his commitment, his artistic oeuvre and the eternal question of whether art can really change the world.

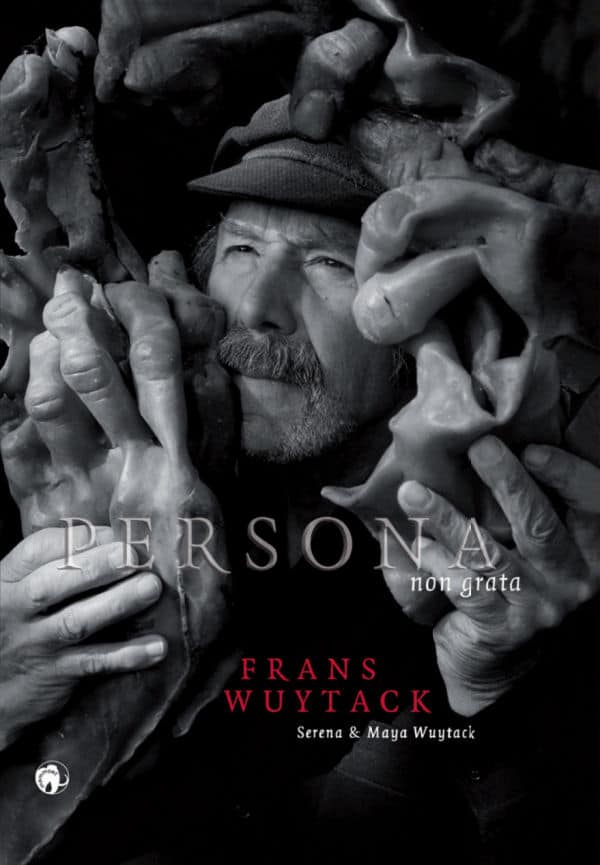

The book that your daughters have dedicated to you is called Persona non grata. Why does that term suit you so well?

Wuytack: “Anyone who stands up against a system of oppression, and who also exerts influence on others in this way, will be banned. I was expelled from the Catholic Church, thrown in jail and sent out of Venezuela. Those in power sit in their palaces and erect walls around themselves, so that they no longer have contact with the people. I’ve always fought against that system, which is also the reason why I’m persona non grata.”

You make robust gesticulations; immediately accentuating your words with firm gestures of the hand.

“The rulers of the earth have brought people together under all kinds of flags. The Flemish, Belgian, Russian or North American ones. But those flags, and the borders that also go along with them, are artificial. But luckily, we all have hands! Hands allow us to cross borders, to reach out to others, to evolve towards a planetary and therefore more human society. To reach out to another beyond the limits of power is also to speak the language of peace. A language that only comes from man himself and is therefore brilliant.”

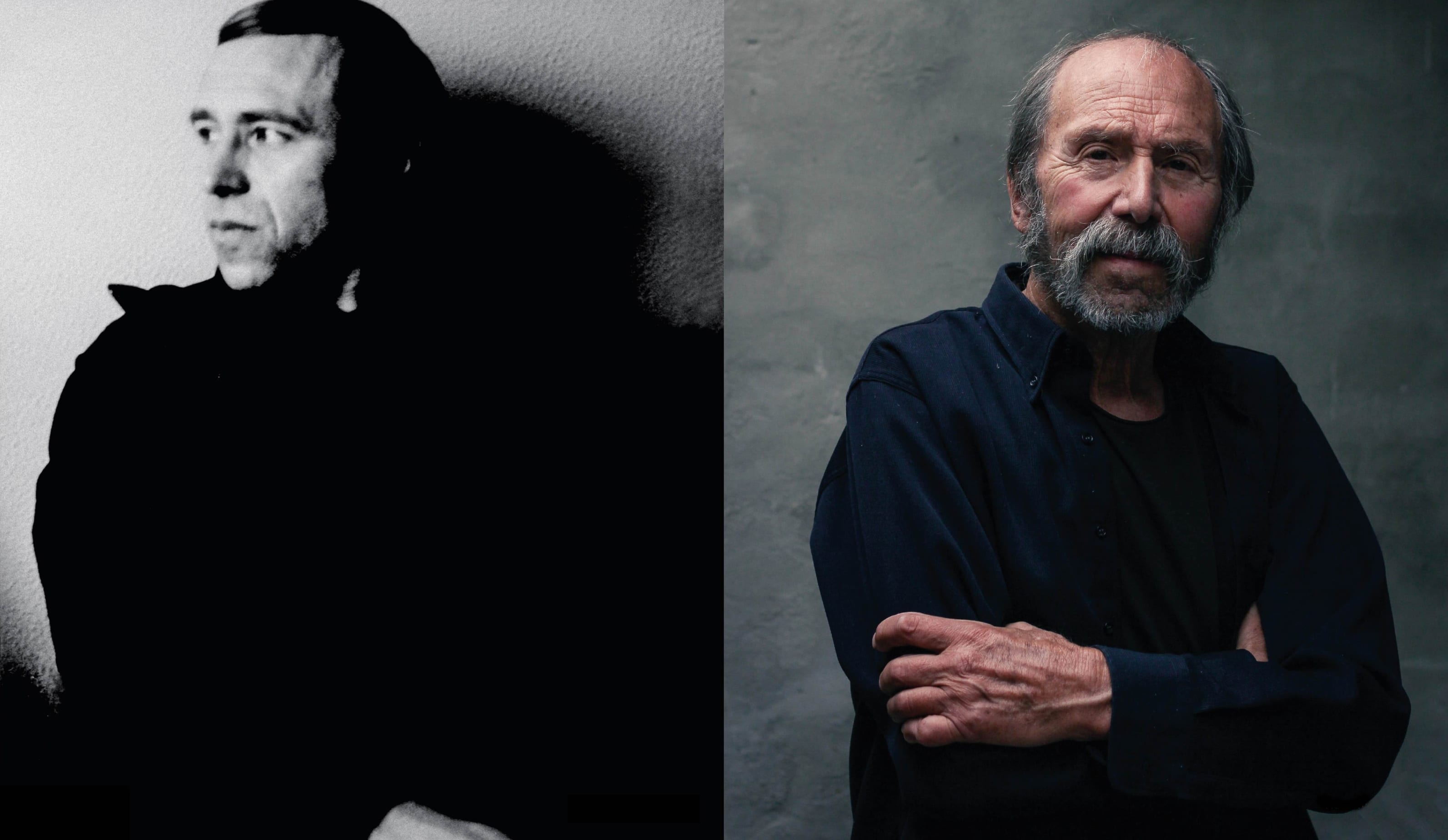

Frans Wuytack

Frans Wuytack© Brecht Vanmeirhaeghe

But your hands are also the instruments of your art. You make art with them, but you also depict them in your art.

“The relationship between art and hands is tens of thousands of years old. Go to the cave of Santa Cruz, deep in Patagonia, in Argentina, and look at all those hands that are handed to us from prehistoric times. These are beautiful, how should I put it, fantastic symbols of proximity, of profoundly human helpfulness. As Sartre said, ‘what language is to the mind, the hands are to feeling’. I’m not a psychologist, but I’ve read that to approach reality, you must look at three things, science, art and religion, and I do the same with my hands, because that’s where the feeling is. Today it is cool to keep your distance, to control reality by separating yourself from someone else. By using your hands, or as the Germans say, to show Fingerspitzengefühl, you accentuate your sensitivity, and you succeed in crossing borders, something we should also give much more space to in education. Life is not only about knowledge; it’s also about feelings. On the road to the process of becoming human, in the hominization or evolutionary development of the human species, hands have proven to be extremely important instruments of feeling. The problem is that we don’t just make art with them but also weapons and atomic bombs.”

Where does your humanity come from? To which specific moment in your long life would you make the connection?

“My first awareness in that regard goes back to my childhood, to the bombings in the Second World War, when I was six and the Stukas flew above the roofs in my hometown of Sint-Niklaas. Hundreds of people were killed and injured at the time.”

“Before the bombs, it still mattered in which street or neighbourhood you lived, or what class you were. But when the bombs fell, that was over. I remember how united people were. It was impressive. The word unity, the idea that we will perish or survive together, sounds so much better than solidarity. It is a great, prehistoric power that was born before the invention of morality, and that we must find again. A power of peace too, which gives life to all mankind – but not the peace of the cemetery, of course, and even less in that of the war cemetery, where only people lie who have been murdered on the orders of the big shots, in the name of ideology, private property and capital.”

Frans Wuytack, 'Broken ground'

Frans Wuytack, 'Broken ground'© Frans Wuytack

Did that solidarity also make you an artist? Did it play a role in that?

“In my childhood, like so many of my peers, I went to art school. Drawing was done in groups and was a very popular event. So, there was solidarity. I come from a neighbourhood where people did a lot of drawing. Today, children are on their smartphones, but when I was a kid, we learned how to draw. Looking at a head and drawing it, very realistic. A whole chunk of emancipation lay behind that learning to look and see. By drawing, I discovered that my method of understanding reality was to see, as in the philosophy of Teilhard de Chardin.”

But then, at the age of fourteen, you start working in a factory, more specifically at the Boelwerf in Temse. How did that go?

“In the seventh and eighth grade, we had a wonderful teacher. He played the violin, also gave gymnastics lessons, and did everything. I have great respect for the patience he had with us. But I came from a working-class family, with a grandfather who was a dockworker and diehard socialist. At the time, for every student who went on to study, there were seven or eight who became factory workers. I was one of the latter, so I left school and went to den Boel, a shipyard with two thousand workers, including a few dozen young guys like me. Those hulks of men who had been working there for twenty or thirty years laughed at us, of course, and called us little kids playing at it. Until one of those ‘little kids was killed, and a syndicalist took up our defence and said, ‘they are not little kids playing’. So that man stood up for reality and opened my eyes. Suddenly, together with other young kids who had left school, I was asked the question: ‘What do you think of your work?’ I remember that as a very powerful moment: when I was allowed to have my own opinion, the power of a thought, regardless of any ideology or religion.”

Frans Wuytack, 'The night of ages'

Frans Wuytack, 'The night of ages'© Frans Wuytack

You were a working-class child; you worked in the shipyard. But in addition to being a worker, you also became a priest. Did that also run in the family?

“My grandfather was religious and said that Christ was the first socialist. In our neighbourhood we also had curate De Bruyne, the crème de la crème of a man, who gave away everything he owned. What an example! In the meantime, I also came in contact with KAJ members (an originally Flemish, now international, Christian youth movement, ld), and was introduced to the ideas of Cardinal Cardijn, who inspired many people with his words that the worker was a beacon of the future. For Cardijn, the dignity of the worker was central. Exploitation was rampant in factories, while the Church was in the hands of the bourgeoisie. We wanted to change that. By seeing, making judgements and acting.”

You had swapped the Boelwerf for a sheet sawmill, learned the trade as a sheet sawer – but then received a late calling.

“There, too, it was one of your mates that got you interested in joining him. ‘Frans, I think I’m going to start,’ said a comrade at one point. I was then taken on for a trial period, and persevered, unlike that friend, who was gone after six months. But I have never been an armchair scholar, I was a man in the field. Of course, I knew liberation theology, but the theory in itself was not for me. I was more interested in the liberation of people of flesh and blood, in the ethics of situations, in daring to act. Okay, you can talk about theology, about revolution, about political parties, about tendencies and movements, but for me it was not essentially about that. For me, it was about being profoundly human, and about the people too.”

Your commitment eventually drove you to Venezuela, to the slum of La Vega near Caracas. How did you do that, apply people’s liberation in practice?

“One of the first things that happened to me there was having my bed stolen. I had only arrived a few days before, taken up residence in a cinder block hovel, and when I came back in at some point, my bed had already disappeared. ‘Francisco, are you sleeping on the floor now?’ some people asked me. It resulted in my bed coming back a week later, completely painted. Well, I never considered that as a theft, but rather an exchange of goods. The real theft is elsewhere, i.e. in the accumulation of property. Just as the crime is not in the child who throws a stone and is arrested by the police, but in the general who is decorated because so many people have died because of his actions and with his weapons.”

What was Venezuela like when you were there?

“It was a rich but colonized country. We had a TV in the neighbourhood, but only twenty-five percent of the broadcasts were Venezuelan, the rest American. The middle class was indeed prosperous, but it had also sold the country to the interests of the US. Under pressure from below, that colonial aspect was gradually removed. In my time, AD and Copei (the then classic parties in power in Venezuela, ld) with their cliques had a strong presence in the neighbourhood. But I didn’t care about that. I was in favour of the liberation of all people. We all believed in only one thing: crossing the line to make a different and better life possible.”

What concrete things did you do?

“Organising the unemployed and setting up strikes in the factories, for example. I remember a strike in which la Negrita, a 39-year-old woman with 10 children, led the way, enthusiastic and proud as hell. That woman could neither read nor write, but believed in dignity and that we could all have a better life together. If we learned to listen to and work together better, we could move mountains, even while the army was surrounding us.”

But you also worked with art there…

“We got people to make drawings, among other things. In the main square of La Vega, we held exhibitions with large, beautiful works of art that imitated Picasso, or we performed plays inspired by Bertold Brecht, such as Mother Courage. One of our biggest sources of inspiration was the socially engaged Brazilian theatre-maker Augusto Boal (with his ‘theatre of the oppressed’, ld). I tried to make people have an appetite for reality through art. By then, my relationship with the Church had long since deteriorated, because the authority of the Church was bound to the authority of the state.”

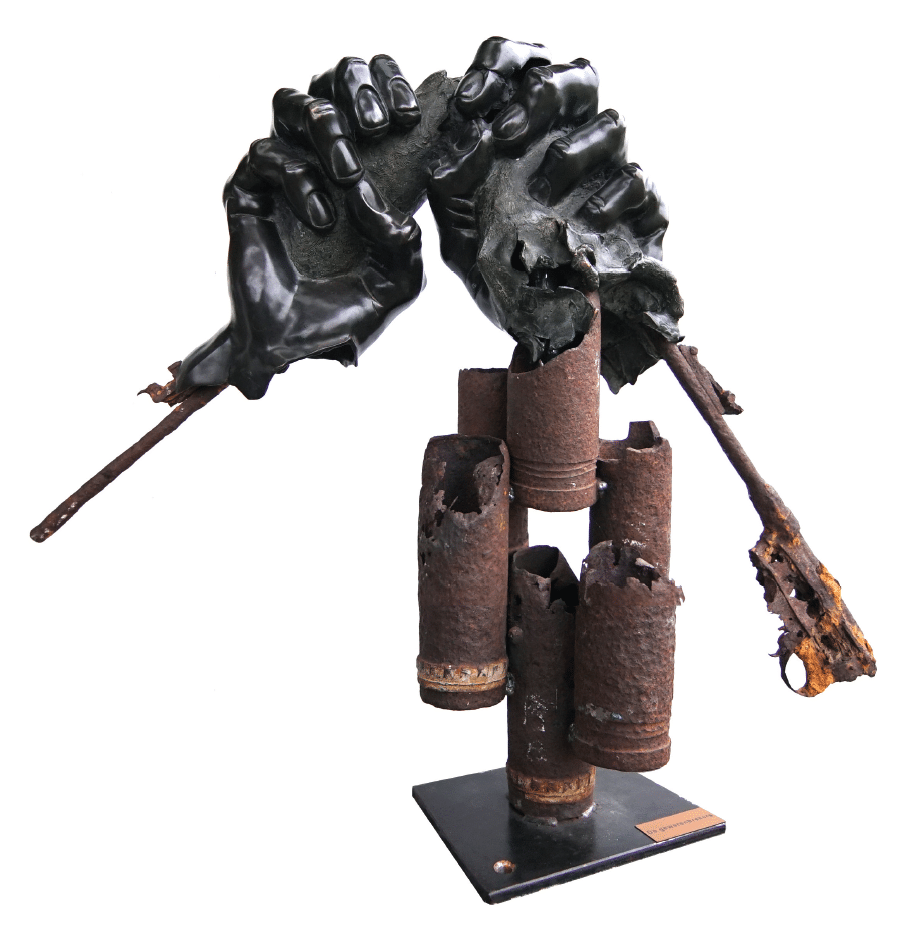

Frans Wuytack, 'The gun breaker'

Frans Wuytack, 'The gun breaker'© Frans Wuytack

The hands with which you made art also took up arms at a certain point.

“That was at the FALN (Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional, a communist guerrilla, ld), yes. The only thing was, I believed in the struggle, but not in weapons. Just as I did not obey what the Church prescribed for me; I did not obey what the commanders said. If you have a gun in your hands, you should always obey the one who gave it to you. I had a hard time with that mandatory submissiveness. I wanted to be with the people, organize the people with the resources they had, so I felt that I wanted to go back to the barrio, the neighbourhood. The guerrilla considered that treason.”

Back to fifty years ago: you were no longer wanted, neither in Venezuela nor in the church. You were also banned from speaking at the Boelwerf. You then worked for three years on the restoration of the cathedral of Antwerp. But in the meantime, you had also met your wife Leen, and you left for Carrara, in Italy. Did that choice, for the city of marble quarries, have anything to do with you becoming a sculptor?

“Not directly. My wife and I wanted to go on a wedding trip, I was 44 by then. So I thought: we’re leaving for a year. But that was a problem for my employer, who threw me out. I couldn’t go on the dole either. So, I figured: I’m going to work in Carrara. I found old digs, with walls eighty centimetres thick, and was able to work in the centuries-old Nicoli studio – where I did indeed sculpt.”

When it comes to sculpture, who are your great examples?

“My first example are the people who work. Those who work with their hands, like the farmer who pulls his plough through the earth. The farmer who ploughs is an artist. Of course, a Picasso, a Giacometti, a Donatello or a Michelangelo, these are people who set the mind on fire, who grasp the suffering of man with the strength of their hands, because that is what art is for. So, the artist should not make art to get worldwide acclaim, but to touch us in our deepest humanity. But the ordinary person who works, and gives substance to reality with his hands, is also an artist.”

Frans Wuytack in his workshop

Frans Wuytack in his workshop© Brecht Vanmeirhaeghe

Isn’t art, first and foremost an individual expression? How do you reconcile the loneliness of the creative process with your urge for the group?

“My expression can be individual, but for me, the collective also lives in the individual. If the individual can say: ‘my hand is not my hand, my hand belongs to the collective’, or if the individual succeeds in crossing the boundary of one’s own self and understands that consciousness only arises when there are two of you, then you will also touch the other person with your own expressiveness. It is going to cross the border again and again. It is not possible to individualize everything; the genius that is in an artist, even if he is not socially engaged, belongs to all of us. In that sense, art is also love. Or as Vincent Van Gogh said: ‘The greatest art is to love each other’.”

To ask with a cliché: can art save the world?

“Art cannot save the world, only consciousness can save the world. The landscapes we see, a vista, everything that comes from consciousness, everything that enables us to keep in touch with the real, with the environment, with the garden in which we live, our earthly paradise, that can save the world – but that is precisely what we are destroying. Because of wars, because of colonization, because of interests.”

Frans Wuytack, ‘Silhouette of impermanence’

Frans Wuytack, ‘Silhouette of impermanence’© Frans Wuytack

And they continue tragically, in the Middle East where you went as a peace activist, and in Putin’s Russia too.

“If my hands were still able, I would chisel a statue for Gaza, but I have written a poem, and I can quote you a passage from it: ‘Pick me up and let me float above the clouds (…) two caged peoples, the same stars, the same wind breathes in our lungs, the same earth colours our blood. Marchands de la mort, drown in your weapons!’ But I also think of those boys in Russia, who are twenty and supposedly fighting for their homeland. Which homeland? The earth is our homeland, they themselves are only cannon fodder.”

“If your hands were still able,” you say. Is it no longer possible?

“I can still manage modelling wax figures, but chiselling and carving are behind me.”

You have led a long and militant life; do you still believe in your ideals?

“More than ever. I believe in man’s decisiveness, in man’s attempt to unleash a world revolution, which will come one way or another. I would like to live to see it – although of course I also say that because I want to live a lot, lot longer.” (laughs)

Serena and Maya Wuytack, Persona non grata. Frans Wuytack, EPO, Antwerp, 2024, 270 pages. Only available in Dutch.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.