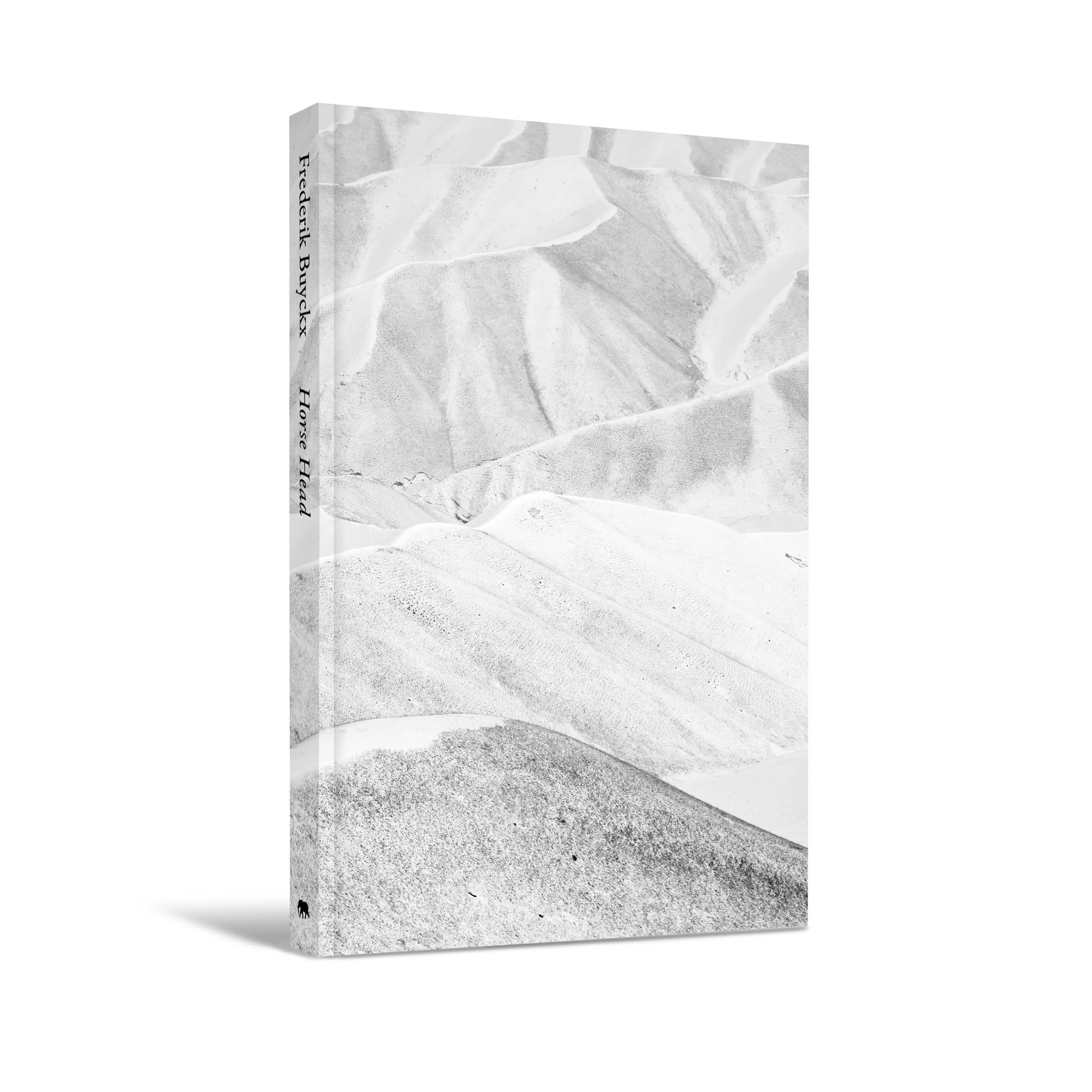

Freedom Without GPS. ‘Horse Head’ by Photographer Frederik Buyckx

How does it feel to cover hundreds of kilometres on horseback in a snowy landscape without civilisation? Photographer Frederik Buyckx depicts this sensation in his book Horse Head.

Frederik Buyckx

Frederik BuyckxIn the past three years, the Ghent photographer Frederik Buyckx (b. 1984) has travelled to Kyrgyzstan seven times. If not for the Coronavirus pandemic, he would have travelled eight times, because, believe it or not, seminomadic shepherds also quarantine themselves.

One might think that seven journeys are an immense effort, but with that view, you will miss an essential layer of the book Horse Head, which is about a man who returns to the vast and barren landscapes of Kyrgyzstan. Also, the insider who decides to introduce us, the readers.

We should be grateful for that. It’s a ten-hour flight to Kyrgyzstan, a country enclosed between Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, China, and Tajikistan. About half of the country is part of the Tensjange Mountains and rises to heights of more than 3,000 meters above sea level. The official language is Kyrgyz, the second language is Russian. In winter, the temperature can sometimes drop to minus forty degrees. Anyone who decides to go hiking without any knowledge of the region will get lost in the middle of nowhere and freeze to death. But that’s if you’re lucky because usually, the wolves do not show that much patience.

As you make your way through the book sitting comfortably on the sofa, Horse Head gives you step-by-step access to an inhospitable area, like a lens zooming in. First, there are pure snowy mountains, then grazing dots of sheep, a single horseman. When humans and animals find each other, we are immediately in the middle of a flock of sheep. We meet the shepherd, his horse, and one of the dogs. Once we discover who the protagonists are, we dive into the action of being on the road – Buyckx marks those passages by switching to a lighter paper that asks for faster browsing. A book can also have cadence.

© Frederik Buyckx / Hannibal Publishing

It is a fascinating black and white world, which you get sucked into. The world of shepherds, who live in farms around the villages and towns and take care of the villagers’ sheep in exchange for a fee. In winter, they take the sheep into the mountains in search of food. They are on the road for weeks and months at a time, transversing hundreds of kilometres of plain flat landscape, without the reassurance of crossing another human-being. Everything comes down to instinct; knowledge is traditional and Buyckx learns by watching. Then, he teaches us how to watch.

The contrast between Horse Head and Buyckx’s second acclaimed book, Jesus, Make-up and Football, can hardly be any greater. Snowy mountains in Central Asia versus sultry favelas in Rio de Janeiro, nature versus man, neutral forces of nature versus hostile violence, black and white versus colour, desolation versus overpopulation. From all this, it becomes clear that Buyckx has lost his soul to the mountains.

© Frederik Buyckx / Hannibal Publishing

But above all, Horse Head shows how incredibly brave the photographer is. It’s a challenging task: compiling a book with only snow, mountains, horses, sheep, a few dogs, and people wrapped up in traditional garments. The book features a guest appearance of only a couple of cows and a dead fox. In black and white. Sheep in herds, sheep in a row, sheep within a fence, sheep scattered like measles on a hillside. And we just watch.

We continue watching because every page exudes the sensation that Buyckx must have felt there and then. It makes you, as a viewer, doubt whether you should be jealous because you did not experience the freedom there, or whether you should be relieved because you can just as well experience the harsh cold within the book. But also, because the whole book has the uniqueness of a miraculous long-term project in an exceptional location, combined with the signature of an award-winning photographer.

© Frederik Buyckx / Hannibal Publishing

The insight into the life of the semi-nomadic tribes in Kyrgyzstan is unique because it is based on trust. Buyckx shows that he is no one-hit-wonder, neither on a human level nor on a professional level. His encounters grow into friendships, his images create commitment – and all without him speaking the local language. This also has consequences for the book: the pictures have no captions. Just like Buyckx, we have to learn to understand by looking. Like the image of the horseman pulling a few wooden beams, nobody explains why this is occurring, but you can imagine something about the value of wood if you consider how few trees are pictured in the landscape throughout the book.

In the essay by the British writer and photographer Lotte Davies recorded in the back of the book, she underscores the photographer’s intimate, almost silent bond with the shepherds. How the desolation of the Tensjang Mountains makes him vulnerable, stripped of city and skin. Davies talks about existential discomfort; Buyckx is drawn to it. And in the same existential reflex, he is attracted to people who can guide him, those who know their way around. It is no coincidence that over the past few centuries, shepherds have become masters in serendipity, intuition, and calmness. But we should not ignore the rough side of their story: the circumstances are extreme, and man and nature can be hard. The title best captures those two faces: Horse Head, or At Bashi in Kyrgyz, which is the name of the village where Buyckx starts and finishes his journey. Legend has it that it is named after a shepherd who was abandoned by his horse in the mountains. Exhausted and slowly starving, he tries to make his way back home and finds the horse on the way back. Out of anger, he cuts off the horse’s head and decides to eat it.

Buyckx continues to return to Kyrgyzstan. For him, it is one of the very few places where beauty does not end after the next post or bench. But Kyrgyzstan also continues to develop, disrupting a long tradition of silence: smartphones and 4G are making their entrance. The before silent trips are now becoming YouTube-trips on four-footed speed. You are grateful for the shepherds; their freedom is so uncomfortable and takes hard work. As long as they continue to find their way without GPS, there is hope.

Frederik Buyckx, Horse Head, Hannibal Publishing, Veurne, 2020, 184 pp.