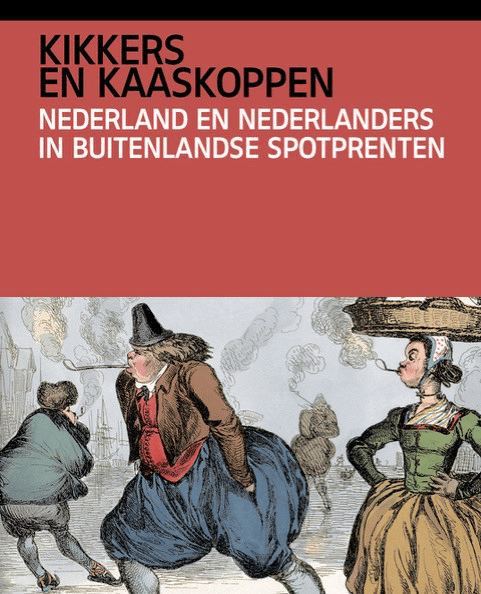

Frogs and Cheeseheads. The Image of the Dutch in Foreign Cartoons

The United Netherlands? May as well call it the United Swamps. And its inhabitants? Frogs and cheeseheads. That’s also the name of an enlightening book full of foreign cartoons from the 17th to the mid-19th centuries, that shows how the Netherlands hasn’t always had a very positive international image.

The Dutch often have a bad reputation internationally. They are blunt, tasteless, rude, and direct – although the latter is sometimes considered positive, as a type of honesty. There are no other people who have provided the Anglo-Saxon world with pejorative expressions as generously as the Dutch have: Dutch stands for confusing (Double Dutch), untrustworthy, (Dutch agreement, Dutch auction), greed (Dutch generosity), deceitful (Dutch sandwich), and much more – the list can be added to ad infinitum.

These idioms may generalise and sound exaggerated, but they do at the same time, have unmistakable historical roots in the real world. Most of this compendium of unflattering national traits is centuries old and closely linked to the expansionism of the Dutch. According to a recent publication by the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum, these verbal caricatures can be effortlessly supplemented with a visual counterpart: a deluge of cartoons with which foreign cartoonists and their public took revenge for all the rudeness and insults they had endured from those big, clumsy, noisy Dutchmen.

With cartoons, foreign cartoonists and their public took revenge for all the rudeness and insults they had endured from those big, clumsy, noisy Dutchmen

Frogs and Cheeseheads is the title of this publication, named after two of the oldest and most established insults. The book, written by Historical Researcher Daniël R. Horst, is made up of around 100 anti-Dutch cartoons from 1600 – 1850, most of which from France, England, and Belgium, but also from the US and Japan. The cartoons are accompanied by in-depth commentary, which describes what we see in the cartoons and to which events or contexts to they relate. We, therefore, see important developments from an international perspective – and the emphasis here is on the visual, which makes the book not only enlightening, but also attractive.

As a geographical and political unit, the Netherlands was an anomaly from the start: the Roman historian Tacitus described the area north of the Rhine as a swampy and difficult to access area of bogs and dark forests. In the additionally cold and wet climate, the people living there had to have been hardy creatures that could adapt easily to impossible circumstances and weren’t easily upset. These characteristics are written about by travellers and writers from the beginning of the new era, including the Italian humanist Lodovico Guicciardini, who settled in Antwerp and wrote influential books on the history of the Low Countries.

Johannes Sadeler (1550-1600)

Johannes Sadeler (1550-1600)© Wikipedia

At about that time, the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (from 1588) was also referred to as the “United Swamps”, a derogatory name for that rude little country, that strange mixture of regions, which nevertheless had such a powerful fleet that it could dominate the world’s seas. The oldest known print depicting the Dutch as frogs in a swamp-like environment was made in 1599, during the Eighty Years’ War (with Spain), by the Southern Dutchman Johannes Sadeler. The frogs (and the mosquitoes) represent the insurgents from the north, but they don’t stand a chance against the mighty towering lion and eagle, which represent the Habsburg Netherlands and the Holy Roman Empire respectively. And so the etching makes clear that the South is loyal to Philip II of Spain.

Then too, wars were accompanied and fueled by propaganda and counterpropaganda, including in the form of pamphlets and cartoons. Shortly after the publication of Sadeler’s print, for example, there was a reaction from the North in which the roles were reversed. This time, the lion is in the service of the freedom fighters of the Republic. With his sword drawn and assisted by the frogs and mosquitoes, he chases the pigs – which represent the Spaniards – into the sea. Another important difference is that Sadeler’s print is an etching, a small edition print intended for consumption by a wealthy elite, with the accompanying texts only in Latin. The northern response was produced as a woodcut, which allowed for faster and larger print runs, and crucially, the accompanying texts were in Dutch.

James Sayers, Patriotic Burghers attacking the House of Orange, 1787

James Sayers, Patriotic Burghers attacking the House of Orange, 1787© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The frog leads a persistent existence in the history of the allegorical cartoon. During the revolutionary turmoil at the end of the eighteenth century, for example, it returns in huge numbers as the embodiment of the rebellious patriots who turned against stadtholder William V and the feudal House of Orange-Nassau. Its role does not tend to be a positive one. In a wonderful British print by James Sayers, Patriotic Burghers attacking the House of Orange (1787), the frog soldiers are depicted as clumsy, farcical, fearful figures, with their French-inspired attack doomed to failure.

The deadly prints by the German cartoonist Johann Ramberg, who worked in England, date from the same period. In his work Rehearsal in Holland 1787, the group of patriots doing target practice is full of idiots; a number of follow-up cartoons show that after the invasion of German troops they have no say against the Prussians and have no choice but to flee to revolutionary France, and that those who can’t are simply humiliated by the Germans in their own country. Prints such as these illustrate where expressions such as Dutch courage (courageous thanks to excessive alcohol consumption) and Dutch defence (hardly any defence) come from.

Johann Heinrich Ramberg, The Rehearsal, 1787

Johann Heinrich Ramberg, The Rehearsal, 1787© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

A shocking lack of discretion and elegance on the part of “the” Dutch is one of the most mocked stereotypes in the book. In a comparative sense, this rudeness is well demonstrated in two prints by Thomas Rowlandson from 1801, in which A Dutch Academy is set next to Royal Academy Sommerset House. The first is housed in a shabby barn where eight smoking, overweight men draw and paint while gawping at a nude model, who is a clumsy, fat woman with her legs spread wide apart.

Thomas Rowlandson, cartoon of the Dutch art academy, 1792, Royal Academy / Somerset House, London, 1801–1811

Thomas Rowlandson, cartoon of the Dutch art academy, 1792, Royal Academy / Somerset House, London, 1801–1811© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The English version is set in a neat, orderly lecture hall. The students are distinguished gentlemen with wigs and have nothing in common with the Dutch rapscallions. The model is a slender lady in a graceful pose, and though naked – not of the unashamedly fleshy school of Rubens – but rather the discreet aristocratic version of Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough.

Thomas Rowlandson, Royal Academy, Somerset House, London, 1801–11

Thomas Rowlandson, Royal Academy, Somerset House, London, 1801–11© The Met, New York

Many of these cartoons require more than a cursory glance. Not only because their intentions only become understandable when one knows something about the conflicts to which they respond and when one is able to decode the allegorical images, but also because they are usually overcrowded and accompanied by lots of text and captions. This is especially true of the English cartoonists – masters of the genre such as Thomas Rowlandson, James Gillray and Isaac Cruikshank, who are amply represented in the book. Their drawings should be less looked at, and more read as stories, often extremely witty commentaries on the happenings of the time.

Fortunately, Daniël R. Horst’s text offers all the desired help. Praise then for this author, whose name, strangely enough, is nowhere to be found on the front cover, spine or back cover, but only just about appears on the inside of the book. A typical case of Dutch consolation.

Daniël R. Horst, Kikkers en kaaskoppen. Nederland en Nederlanders in buitenlandse spotprenten (Frogs and Cheeseheads. The Netherlands and the Dutch in Foreign Cartoons), Boom, Amsterdam, 2021, 192 pages. The book is published only in Dutch.