From Abbey to Architectural Icon. Two Centuries of the Ghent University Library

‘A mighty bookcase reaching to the skies’: that was architect Henry Van de Velde’s plan for the building that we now know as the Boekentoren in Ghent – the “Book Tower”. But the history of the university library is more than that imposing bit of skyline, as shown by historian Ruben Mantels in his new book Towers of Books.

Ghent University Library’s Book Tower looms large over the historic Rozier, its success story is one worth telling: The restoration of Henry Van de Velde’s (1863-1957) iconic building is finished, and the collections are now largely digitized. But the road to success has been all but linear. Ruben Mantels’ exemplary study Towers of Books. Ghent University Library 1797 – 2020 exposes the inevitable obstacles that stood in the way of this projects’ completion.

The skyline of Ghent with St Bavo's Cathedral and the Book Tower

The skyline of Ghent with St Bavo's Cathedral and the Book Tower© Michiel Hendryckx

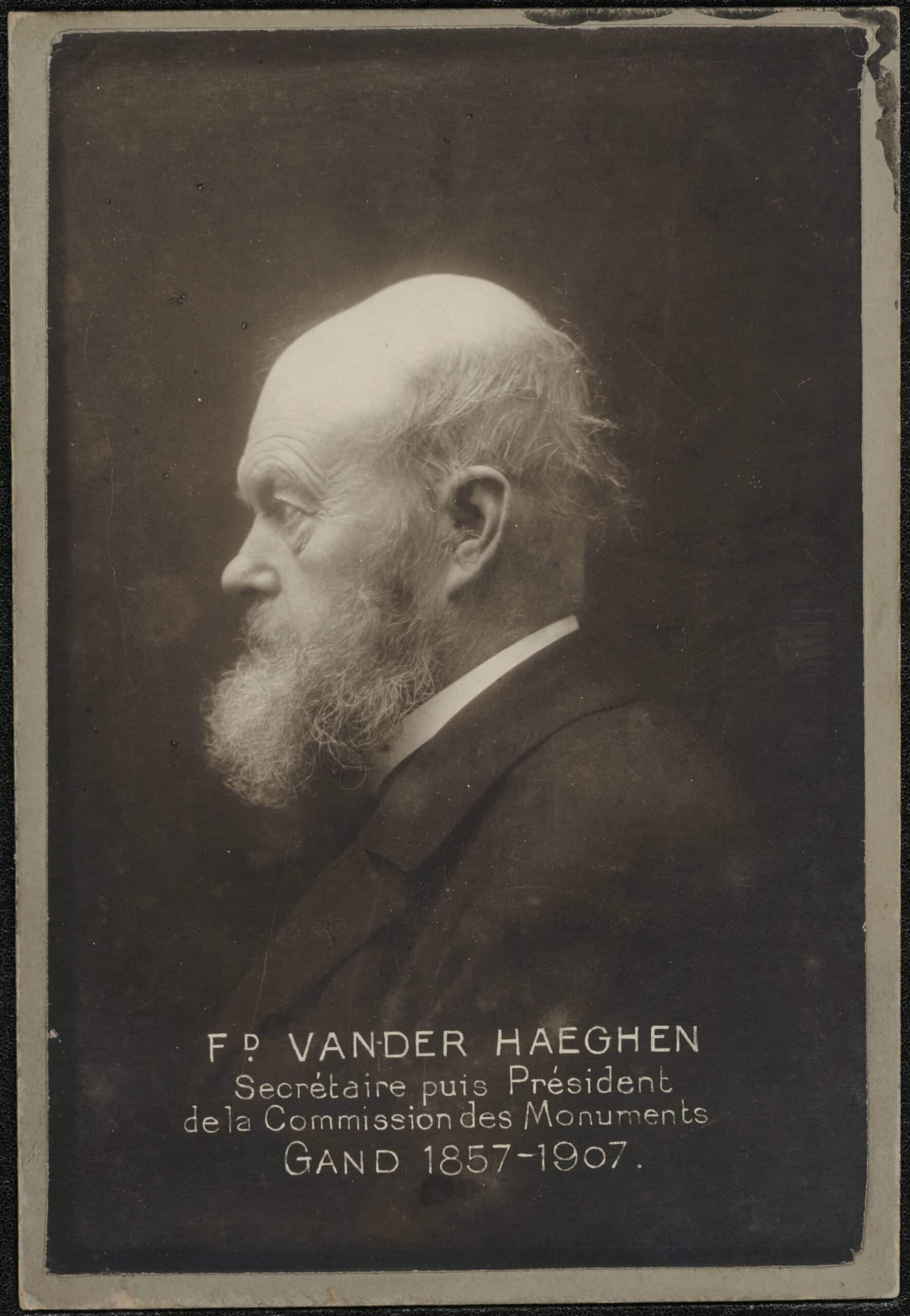

Over the years, not one but several head librarians were asked to step down. This was often because, in one way or another, it was deemed that the times had caught up to them. Such was the case of Ferdinand Van der Haeghen (1830 – 1913), who ran the library from 1869 to 1911. Through acquisitions and donations, he succeeded in expanding the book holdings from 80,000 volumes to nearly 400,000 strong. Together with his predecessor Karel Van Hulthem (1764 – 1832), who was just as erudite a bibliophile, he is considered the founding father of the expansive and valuable collection that is housed on the Rozier today.

Ferdinand Van der Haeghen ran the library from 1869 to 1911.

Ferdinand Van der Haeghen ran the library from 1869 to 1911.© Ghent University archives

Up until the First World War, the extensive facilities of Ghent University Library were primarily enjoyed by a niche circle of historical and philological researchers – some of them ‘professors’ and others not. In 1863, one was even allowed to bring home the Liber Floridus (“a beautiful illuminated medieval encyclopedia dating from 1121”). In 2008, this Liber Floridus was recognized as a masterpiece by the Vlaamse Gemeenschap.

The university library, which also served as a city library until 1942, was originally a product of the French Revolution. After the annexation of Flanders by France, the civil authorities seized and confiscated goods from monasteries and other religious institutions throughout the region (which was then known as the Southern Netherlands and the Prince-Bishopric of Liège). This included precious library collections. Those items taken from the Ghent region ended up in the Baudeloo monastery on the Ottogracht, which was opened to the public as a library in 1801.

The university library was originally a product of the French Revolution

Willem de Vreese (1869 – 1938) was the first professor to lead the university library in 1911. It did not take long for this scholar of Middle Dutch to emerge as an innovator of the institution. Not only did he introduce the typewriter, the telephone, and the vacuum cleaner, he also recruited the first female member of staff. Before fleeing to the Netherlands at the end of the First World War to escape persecution for his activism, De Vreese managed to implement the collection’s first complete index card cataloguing system in a relatively short period of time and with very limited library staff.

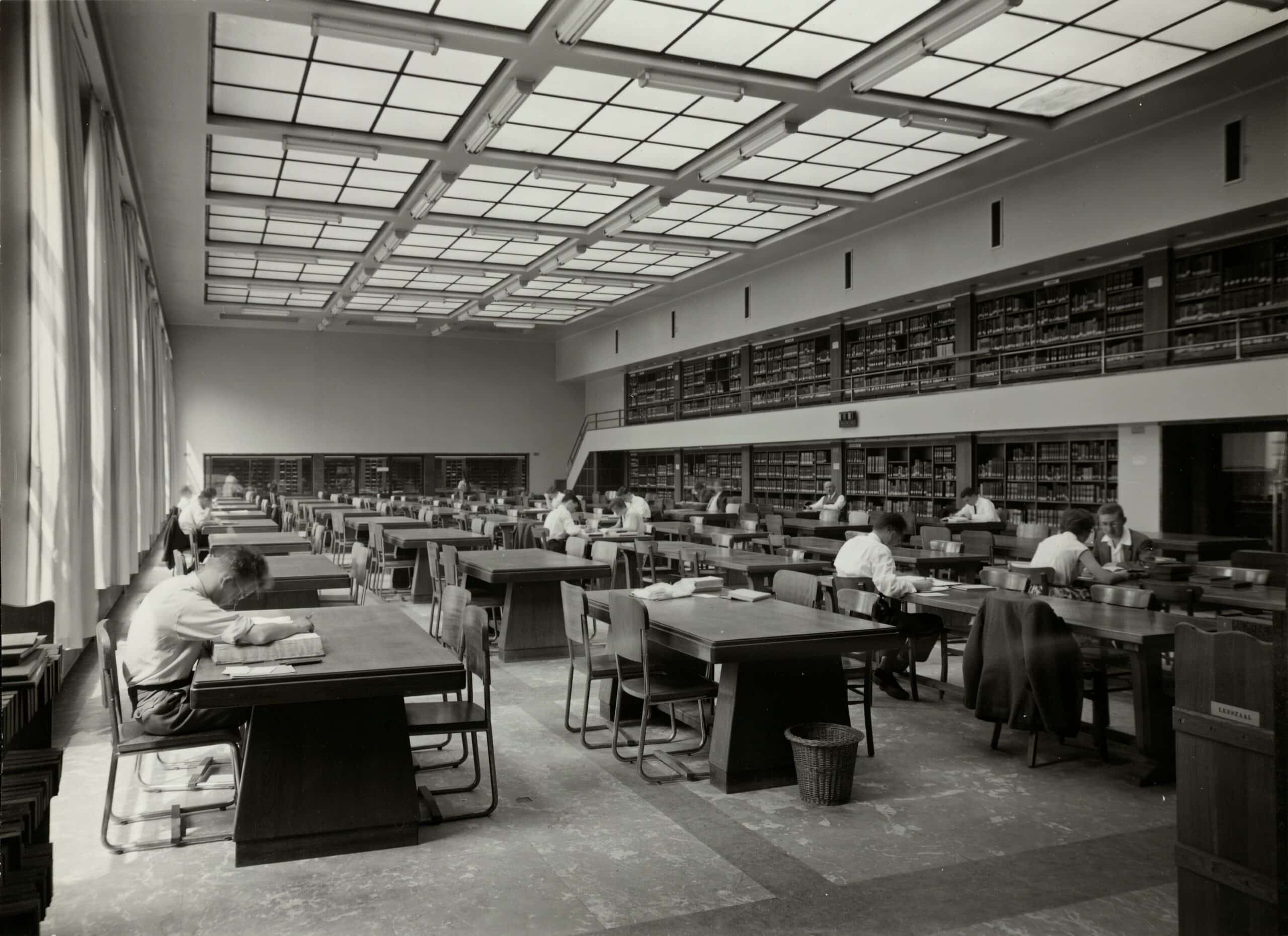

The reading room of the Book Tower

The reading room of the Book Tower© Book Tower Collection / Paul Bijtebier

Yet another historic moment followed a decade later – the decision was taken to celebrate the recent Dutchification of the university with a new library building. Director August Vermeylen (1872 – 1945) passed this honourable task to his childhood friend Henry Van de Velde, who developed a plan for a tower that he himself described as “a mighty bookcase reaching to the skies”. The foundation was laid in 1936, and the new library opened its doors in 1942. Collections were relocated from their wartime home on the Ottogracht, where the city library remained, but upon its opening, the Book Tower was by no means the Gesamtkunstwerk that Van de Velde had envisaged – certainly not as far as the interior was concerned. The completion of the building would drag on until 1960, three years after his death.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the institution had slowly but surely been losing its grip on the many other libraries within the city

After the Second World War, the architectural bravado of this new Book Tower gave Ghent University Library a contemporary home with a certain cachet. At the same time, throughout the nineteenth century, the institution had slowly but surely been losing its grip on the many other autonomous, seminary, institutional and laboratory collections within the city (and later also on the outskirts of the city). By 1994, there were no fewer than 339. Because of this fragmentation, as Ruben Mantels rightly puts it, there was talk of “a dual library system”. It was not until after the year 2000 that rational thought prevailed and an operational network of faculty libraries was established – these smaller collections are now overseen by the Book Tower while retaining a certain degree of independence.

The 1960s also ushered in the revolution that would turn librarians into bona fide information scientists: “first the electronic, then the virtual, and finally the digital library”. As this transformation was underway, the ongoing economic crisis of the 1970s forced the library to make drastic cutbacks. So much so, that towards the end of 1982 the head librarian informed the director (with a certain melodramatic flair) that in the past three years not a single monograph had been purchased, not a single book had been bound, and not one material investment had been made.

© UGent/photo by Hilde Christiaens

And yet the high-tech changes went ahead: In the competitive academic landscape, falling behind was not an option. As the economy bounced back, a renewed library policy was drawn up and put into practice. In the long run, this ultimately led to the pivotal moment in 2007 when a groundbreaking deal was signed with Google Books – the American tech giant digitized the library’s approximately 250,000 “printed books from before 1870 (excluding large-format editions)”. The valorization and wide-spread publication of rich heritage collections both in real and digitized form are now, alongside its devoted library service to the university community, the second pillar of Ghent University Library.

The belvedere at the top of the Book Tower

The belvedere at the top of the Book Tower© UGent/photo by Geert De Soete

At the end of 2005, it was decided that the library building, classified as a monument since 1992, would be completely restored from tip to toe and a new underground depot added. The large-scale project was not effectively begun until 2013 and is now completed. It was, in fact, the imminent completion of these renovations that spurred on the publication of Ruben Mantels’ painstakingly produced monograph, the idea for which was originally initiated by head librarian Sylvia Van Peteghem (who retired in 2020).

Ruben Mantels (trained as a literary historian in Leuven, now working in Ghent) has written a particularly accessible and balanced synthesis based on extensive and diversified sources. The history of Ghent University Library is brought to life through a wealth of both human and historic anecdotes. Aside from a few repetitions, a few odd turns of phrase (more so in the first half of the book), and a lack of comparisons to other academic libraries, there’s little to no fault in this superbly illustrated monograph. It forms a beautiful tribute to this stately but by no means static grande dame, which since the retirement of the first female head librarian is now once again run by a man.

You can download Towers of Books for free via this link (Apple Books) and this link (Google Books).