From Clara to Bokito: The Wilderness in Our Zoos

Every year, Dutch and Belgian zoos bring nearly fifteen million visitors face to face with exotic animals. Our fascination for and exploitation of wild animals has a long history that reveals major social changes: from prestige projects for medieval monarchs to experiences for the general public. Raf De Bont recounts that history in a story starring Clara the rhinoceros, Jack the elephant and two gorillas named Gust and Bokito.

In 2022, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam launched an exhibition that, unusually, was not devoted to an artist or historical figure, but to an animal: an Indian rhinoceros named Clara. The rhinoceros landed in Rotterdam in 1741 and was the first of its kind in the Low Countries. For two decades, Clara was dragged through Europe in a wooden cart as an attraction. Public interest was huge, and Clara found herself at the root of a true rhinoceros mania.

In the eighteenth century, it was, of course, quite an undertaking to introduce a rhinoceros from India to spectators in cities such as Amsterdam, Groningen or Brussels. After being captured in Assam during a royal hunt, Clara first ended up in Hougli, Bengal, a Dutch East India Company (EIC) trading post. There, she became the property of EIC captain Douwe Mout, who shipped her to Rotterdam – a journey that lasted more than ten months. Once back in Europe, Mout began almost immediately to travel with Clara to both the royal courts and to public fairs, where the public could see and touch her for a fee. Clara was an object of amazement, precisely the revenue model Mout had in mind. The whole enterprise was made possible by the colonial infrastructure and exuded a colonial merchant spirit.

EIC captain Douwe Mout travelled with the Indian rhinoceros Clara to both the royal courts and to public fairs, where the public could see and touch her for a fee.

EIC captain Douwe Mout travelled with the Indian rhinoceros Clara to both the royal courts and to public fairs, where the public could see and touch her for a fee.© Wikimedia Commons

Appropriating, shipping and displaying exotic animals like Clara has a long history – a history that connects the Low Countries with the rest of the world. It is also a history that reveals significant changes both in the way animals were transported from distant lands and in the way they were exhibited.

Courts and fairgrounds

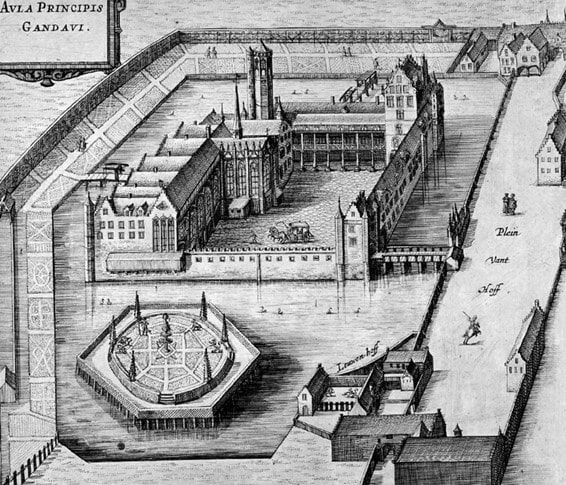

Clara may have been the first rhinoceros in the Low Countries, but her story is part of a tradition that goes back much further. In the European courts of the late Middle Ages and early modern era, rare animals were regarded as prestigious, status-conferring possessions. From the fifteenth century onward, noble families kept menageries. The dukes of Burgundy, for example, maintained a small menagerie at the Prinsenhof in Ghent and another at the Coudenberg Palace in Brussels. Lions in particular – with their dynastic and heraldic significance – occupied a prominent place in the collections. A noble public was allowed to come and see the rarities and could also (after the Roman example) watch exciting fights between animals.

The Prinsenhof in Ghent with the Lion's Court at the front right

The Prinsenhof in Ghent with the Lion's Court at the front right© Flandria Illustrata, Antonius Sanderus

The Habsburgs continued this tradition in the Southern Netherlands into the sixteenth century. At the same time, provincial executive officer Maurits of Oranje built his own menagerie in Rijswijk, in the north. That was the beginning of a long fascination the Oranjes had for exotic animals – a fascination that, in the eighteenth century, culminated in the spectacular animal collection of Willem V in Hofstede De Loo, in Voorburg. As in most princely collections, birds took centre stage, but at Voorburg there were also elephants and a chimpanzee. From the Burgundians to the Oranjes, collections like these were regarded as symbols of power, wealth and learning.

The expansion of colonial trade in the sixteenth century resulted in a rapid increase in the supply of exotic animals to the Low Countries. It was also in this period that the French term exotique made its appearance – not coincidentally for the first time in a list in which animals, along with tapestries and paintings, were mentioned as commodities. Colonial organisations such as the EIC played a key role. They supplied nobles such as Willem V, but, as the case of Clara illustrates, also fed a more commercial circuit.

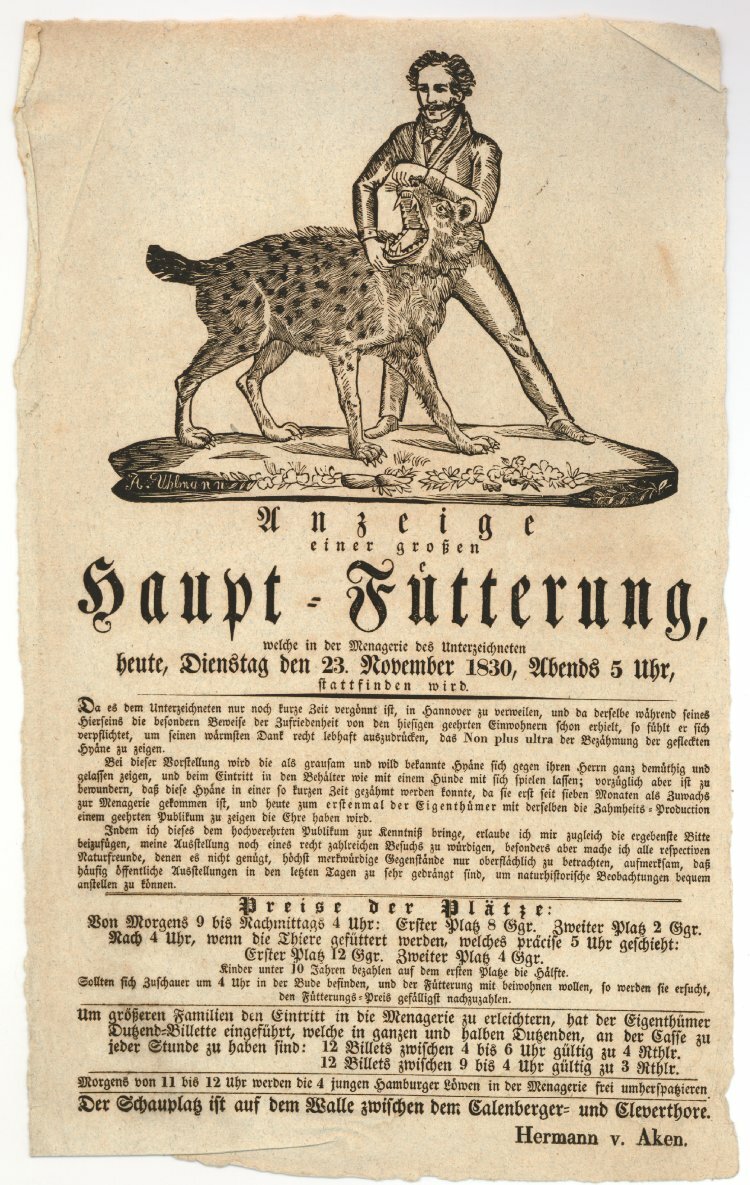

Mout’s tours with Clara provide an early example of the itinerant menageries that would flourish between 1750 and 1850. One of the biggest players in Europe eventually became the Van Aken’s of Rotterdam, whose family history nicely illustrates how Wandermenagerien or travelling menageries influenced modern zoo and circus practices. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Van Aken senior had an exotic animals business in Rotterdam, while his children visited the fairs with specimens from his collections. His son-in-law, the Frenchman Henri Martin, was known for his equitation skills. After he married into the Van Aken family, he was retrained to become a travelling lion and tiger tamer. In this way, he provided an influential model for future circus acts. At the end of his extremely successful career, Martin sold his animals to his brother-in-law Cornelis van Aken. Cornelis then passed on the collection to Artis in Amsterdam – the first public zoo in the Low Countries, founded in 1838. Cornelis himself served as the treasurer (until he was fired for alcohol abuse three years later). Martin also stayed active in the business: in 1857 he became the first director of Blijdorp Zoo in Rotterdam.

Poster for a show at the menagerie of the Rotterdam Van Aken family. Such travelling animal shows are at the origin of modern zoo and circus practices.

Poster for a show at the menagerie of the Rotterdam Van Aken family. Such travelling animal shows are at the origin of modern zoo and circus practices.© Wikimedia Commons

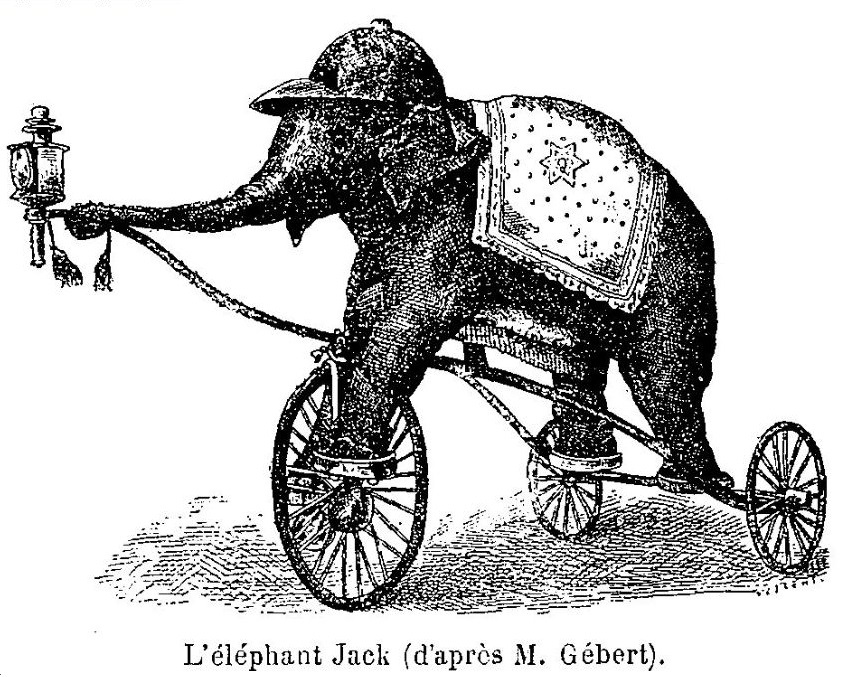

The story of the interplay between itinerant menageries, circuses, animal dealers and zoos can be recounted through the stories of individual animals as well as those of individual people. There was the Indian elephant Jack, imported from Ceylon, who travelled around Europe as part of Van Aken’s menagerie. Like Clara, Jack’s appeal lay partly in his spectacular size and weight, but he also took part in some “circus arts, ” creating added value. Jack ended his life, just like his former owner, at Artis. The elephant – permanently chained – exhibited increasingly aggressive behaviour. In the end, he was shot (by the director himself) when he became too unmanageable.

Indian elephant Jack, imported from Ceylon, toured Europe as part of Van Aken's menagerie.

Indian elephant Jack, imported from Ceylon, toured Europe as part of Van Aken's menagerie.© Wikimedia Commons

World trade and the bourgeoisie

With the foundation of Artis (1838), the transport logistics and staging of exotic animals took on a new cultural form: the bourgeois public zoo. The model came from the United Kingdom, but the Low Countries played a pioneering role in the development of public zoos on the continent. After Artis in Amsterdam, zoos were soon founded in Antwerp (1843), Brussels (1851), Ghent (1851), Rotterdam (1857), The Hague (1863) and Liège (1865). The founding organisations were usually natural history societies with lofty ideals such as the promotion of scientific knowledge and the acclimatization of exotic species – factors that worked to stimulate the economy. The hope was that zoos could become places where exotic animals could be studied, domesticated, and made useful – as alternative sources of meat, wool, or as a pulling force in transportation. In practice, none of this came to fruition, and the focus quickly shifted to recreation.

The Low Countries played a pioneering role in the development of public zoos in Europe

The founders belonged to the emerging urban bourgeois class who had benefited from the Industrial Revolution and an expanding global trade. The zoos, therefore, had to embody the values of this class: belief in progress, cosmopolitanism and national pride, colonial ambitions, good taste and scientific interest. The civil zoo was a place to stroll in a clearly ordered and picturesque world. In addition to the animal exhibits, the visitors could enjoy flowerbeds and restaurants, kiosks, exhibition spaces and concert halls. The working class was kept out. The price of membership or even an individual entry ticket was beyond the capabilities of the average worker. And even in the exceptional case that a working-class candidate did amass the wherewithal to apply for membership, the doors remained closed. In 1848, for example, a group of country people were refused entry to the Antwerp zoo, solely on the basis of their clothing.

Strolling past the elephant enclosure in The Hague's Royal Zoological-Botanical Garden, circa 1865

Strolling past the elephant enclosure in The Hague's Royal Zoological-Botanical Garden, circa 1865© Print collection Hague municipal archives

Improvements in logistics enabled a permanent supply of exotic animals. The public zoos of the Netherlands and Belgium developed in tandem with the railways, ports and shipping companies that drove the nineteenth-century economy. The societies partly counted on donations from diplomats, shipowners and colonial officials for the purchase of animals. They occasionally organised trapping expeditions, but they bought most of the animals from a slowly growing number of animal dealers. Some zoos (Antwerp in particular) also became important sales hubs themselves. The Low Countries benefitted from a constant flow of animals from the interiors of Africa, Asia and America. This was necessary because mortality rates were high along the entire supply chain. Animals died in large numbers during their brutal capture and lengthy transport, and also in the cramped, poorly ventilated and unheated cages at their final destinations.

In 1848, a group of country people were refused entry to the Antwerp zoo, solely on the basis of their clothing

The cramped housing of animals in nineteenth-century zoos was related to the founders’ scientific ambitions. Like the natural history museums that were booming in the same period, zoos wanted to offer their visitors complete and encyclopaedically arranged collections of species. The decoration of the buildings housing these “living catalogues” was often quite spectacular. The cosmopolitan self-image of the founders was translated into richly decorated Orientalist architecture. Such luxury was, of course, intended for the human eye. Nineteenth-century staging had little to do with the welfare of the animals.

The human-centred focus of the staging is extensively demonstrated by historian Violette Pouillard in her book Histoire des zoos par les animaux: imperialisme, contrôle et conservation (2019) (History of Zoos from the Animals’ Perspective: Imperialism, Control and Conservation). She describes how animals in cramped, cold and muddy enclosures were susceptible to all kinds of diseases. Visitors were invariably allowed to come extremely close to the cages, which not only caused stress and disease transmission, but also encouraged violence against the animals. In addition, visitors were allowed to feed the animals, often with inappropriate food. Natural group sizes were thoroughly disrupted. Stereotypical behaviour and self-mutilation were widespread among the animals. One of the many examples Pouillard cites is that of a rhinoceros that stood in the same place in the Antwerp zoo for almost thirty years – its horn completely worn off from rubbing against the bars.

Artificial rocks, sanitation and breeding programs

After years of boom, declining membership and visitor numbers made the community zoos vulnerable from the late nineteenth century. In Belgium, the zoos of Brussels (1878), Ghent (1904) and Liège (1905) closed their doors. In the twentieth century, the lack of enthusiasm for the remaining zoos was exacerbated by two world wars with a severe economic crisis in between. In the late 1930s, municipal intervention was required in Amsterdam and Rotterdam to avert bankruptcy. The zoo in The Hague closed its doors in 1943. And yet, it would be a mistake to see the zoo as a prototypical nineteenth-century phenomenon. The crisis was temporary. While the community zoos were running into problems, new initiatives were already being started. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the number of zoos in the Low Countries ultimately increased.

Since 1900, the number of zoos in the Low Countries increased

Especially in the Netherlands, there were already new founders in play during the interbellum period. It was no longer civil societies, but small entrepreneurs who set the tone. The initiatives came from individuals: a butcher, a chicken breeder, an automobile importer. These entrepreneurs did not settle in the big, expensive cities but sought space in the provinces: in Arnhem (1923), Rhenen (1932) or Emmen (1936). This new access to space also made new forms of staging possible. Burgers’ Zoo in Arnhem, for example, was inspired by Carl Hagenbeck’s Tierpark in Stellingen to omit bars and exhibit animals behind canals, in terraced landscapes complete with artificial rocks. According to the rhetoric, this gave animals more freedom, but in practice the barriers had, of course, not disappeared. They were only hidden from the view of the visitor.

Zoo design in the Low Countries was clearly subject to international trends. In the early twentieth century, various zoos tried to integrate elements of Hagenbeck’s philosophy, but in the middle of the century the so-called “sanitation style” emerged. Bare modernist spaces made of glass and concrete would offer better options for lighting, ventilation, heating and hygiene. Animals were shown in an atmosphere of practicality and rationality.

Modernism for penguins, Artis, 1935/1936. In the early twentieth century, animals were shown in an atmosphere of pragmatism and rationality.

Modernism for penguins, Artis, 1935/1936. In the early twentieth century, animals were shown in an atmosphere of pragmatism and rationality.© Archive Jaap Kaas, Amsterdam City Archives

Around 1970, the emergence of new zoo concepts led to even further diversification. For example, safari parks such as Beekse Bergen in Hilvarenbeek in North Brabant (1968) and Le Monde Sauvage in Aywaille in Liège (1975) appeared; places where visitors could view lions from the safety of their cars. The trend responded to increasing car ownership and offered middle-class residents a domestic alternative to the emerging safari tourism in East Africa. Following on from the success of the American TV series Flipper, dolphinariums were founded in the same period, including in Harderwijk (1965) and Bruges (1972). Like lions and elephants in (still popular) circuses, dolphins were trained to perform “tricks” in front of seated audiences.

Such forms of training came under increasing criticism and from the start of the 1990s many zoos once again pursued an aura of “naturalness”. The era of the “immersive” zoo had begun: the aim was to immerse the visitor in the habitat of the animal. Ibises and lemurs were housed in jungles with artificial waterfalls while gorillas gambolled in masonry volcanoes. In an echo of nineteenth-century Orientalism, Asian temple ruins and African mud huts were integrated into the staging. Sometimes these involved small-scale adjustments to existing zoos, but there were also newly purpose-built theme parks such as Pairi Daiza in Brugelette (1993) or the Wildlands Adventure Zoo in Emmen (2016). Yet, despite this carefully orchestrated immersion, the main focus was again on the human visitors, rather than the animal inhabitants.

From the mid-twentieth century, old zoos increasingly played the conservation card

Simultaneously with the changes in the design, there was also a change in self-legitimization. From the mid-twentieth century, old zoos – in particular Antwerp and Amsterdam – increasingly played the conservation card. The role of zoos was to concentrate on nature education and the breeding of endangered species. Much money was spent to acquire iconic rarities such as the northern white rhinoceroses Paul and Chloe that were flown from Sudan to Antwerp in 1950 with great fanfare. Zoos began to rely on veterinary research to boost breeding success, which had traditionally been a weak point. In the 1960s and 1970s, herd books and exchange programs were established to promote worldwide collaboration between “scientific” zoos. International legislation such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) made it more difficult to import animals from the wild after the early 1980s. Contacts with animal dealers were gradually broken and supply lines changed. The ideal became that of a closed circuit in which zoos exchanged and bred individuals to protect their genetic diversity worldwide.

A lion in Natura Artis Magistra (1897) and a tiger in Artis (circa 1938)

A lion in Natura Artis Magistra (1897) and a tiger in Artis (circa 1938)© Collection B.W. Stomps / Archive Jaap Kaas, Amsterdam City Archives

Gust and Bokito

Change and continuity in zoo policy in the late twentieth century is well illustrated by the life stories of two well-known lowland gorillas: Gust (born in 1952) and Bokito (born in 1996). Gust was captured as a youngster in an unknown place in the Central African rainforest and brought to Antwerp by plane. The trauma of capture, transport and change in his social and natural environment had a negative impact on his physical and mental health. Gust was quarantined for three years, during which he contracted lead poisoning from gnawing at the paint on his cage. After being denied contact with other gorillas for five years, he was placed with the female Kora – in contradiction to the specific social structure of lowland gorillas. There were no descendants. In 1959, the “couple” was housed in the new monkey building, where they were allocated a bare space of 4.5 by 4.5 meters behind double glazing. Gust, in particular, displayed stereotypical stress behaviour, but that did not detract from his popularity. Until his death in 1988, large groups of visitors gathered at his cage. Often, they would bang on the glass to get his attention – looking for a brief moment of “contact”.

Bokito's enclosure (1996-2023) at Blijdorp shows the paradox of exhibiting animals: his artificial environment with concrete and cameras was dressed up as 'natural'.

Bokito's enclosure (1996-2023) at Blijdorp shows the paradox of exhibiting animals: his artificial environment with concrete and cameras was dressed up as 'natural'.© Unsplash / Ronald van der Graaf

Bokito offers – at least in part – a different story. His “African” name, in contrast to the Flemish Gust, betrays a postcolonial sensitivity. However, Bokito was not born in the wild, but in the Hamburg zoo. At the age of nine he was moved to Blijdorp in Rotterdam as part of an international breeding program to combat inbreeding. Bokito ended up on an artificial gorilla island with a larger group of conspecifics, and was able to reproduce successfully. He gained his greatest notoriety when he escaped in 2007 and injured a woman who had systematically made eye contact with him. The incident forced Blijdorp to make adjustments. They put foil on the windows and installed cameras for surveillance. Nowadays, Blijdorp is developing a gorilla enclosure with a “wooded outlying area”. It focuses on “special encounters”.

All this shows the tightrope on which zoos dance. An extremely artificial environment of concrete and cameras is decorated to look “natural”. The gaze of visitors is directed towards exotic animals while, at the same time, the animals must be shielded from the human gaze. The “special encounters” are accurately staged and implemented. Yet, sometimes things still go wrong. The Rotterdam gorillas were infected with COVID-19 in 2021 by human visitors.

Sharp paradox

Bokito is part of a long tradition. Since the late Middle Ages, various players have organised brief moments of “contact” with wild, exotic animals. Different social classes were involved: aristocrats at court, broader layers of the population at the fair, the upper middle class at the community zoos and the middle class at the contemporary zoo. Over time, the fascination for exotic animals in the Low Countries has only grown. Until the 1970s, that growth was fuelled by commercial extraction of species from the wild; since then collections have increasingly been built up from a supply of globally circulating animals bred in captivity.

The paradox of exhibiting exotic animals has only become sharper in recent decades. The animals shown today were born in world cities, are vaccinated, receive appropriate food and live in air-conditioned rooms with cameras. At the same time, their “wild” geographic origins are increasingly highlighted – both through the conservation stories in which they act as “ambassadors” and in the fake jungles of their residences. Millions of visitors are seduced by safe adventures in a tamed wilderness.

From Clara to Bokito, one factor has remained central: a human desire for the sensation of briefly interacting with wonderful creatures from another, wild world.

This article was written within the Vici project Moving Animals (VI.C.181.010), funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

Literature

- Roland Baetens, De roep van het paradijs: 150 jaar Antwerpse zoo, Lannoo, Tielt, 1994

- Eric Baratay and Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, Zoo: A History of Zoological Gardens in the West, Reaktion Books, Hong Kong, 2002

- Irus Braverman, Zooland: The Institution of Captivity, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 2013

- Gijs van der Ham, Clara de neushoorn, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2022

- Wessel Broekhuis, ‘De verbrijzelde ribben van olifant Jack’, in: Wonderkamer: Magazine voor wetenschapsgeschiedenis, 1 (2020), pp. 58-60

- Donna C. Mehos, Science & Culture: For Members Only: The Amsterdam Zoo Artis in the Nineteenth Century, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2006

- Florence Pieters, Arie van den Berg and Marja Keyser, ‘Menagerieën op de kermis: oorsprong van circus en dierentuin’, in: Johanna Jacobs (ed.), Kennis, kunstjes en kunnen. Kermis: De wondere wereld van glans en glitter, SUN, Amsterdam, 2002, pp. 58-74

- Daniel Lievois and Baudouin van den Abeele, ‘Une menagerie princière entre moyen age et renaissance: La cour des Lions à Gand de 1421 à 1641’, in: Richard Trachsler, Baudouin van den Abeele en Paul Wackers (eds.) Reinhardus : Yearbook of the International Reynard Society, 24 (2012), pp. 77-107

- Violette Pouillard, Histoire des zoos par les animaux. Impérialisme, contrôle, conservation, Champ Vallon, Cheyzérieu, 2019

- Violette Pouillard, ‘Gust (ca. 1952-1988), or a History from Below of the Changing Zoo’, in: Tracy Mc Donald and Daniel Vandersommers (eds.) Zoo Studies: A New Humanities, Kingston, McGill-Queens University Press, 2019, pp. 167-190