From Dutch Alps to Double Dutch. When Dutch Means No Good

If there’s even a grain of truth in all the sayings that feature the Dutch, then it’s not looking too good for the Dutchies. The Netherlands is full of greedy boozers, we’re all druggies, immoral behaviour is our speciality and we very much struggle to make ourselves understandable. But does the word Dutch

always mean people from the Netherlands? For his book De Dutchionary, language journalist Gaston Dorren has collected at least 400 old, new and timeless sayings that include the word Dutch. He was struck by the interesting origin of this extraordinary word.

Straight away, Dorren has a reassuring statement for those of us that are concerned about our country’s image – many sayings have little or nothing to do with the Netherlands. Indeed at different times and in different places, different groups of people have been called Dutch. During the early Medieval period, Dutch was just a word used by the English to describe ordinary or everyday matters. This description didn’t only apply to the English, it extended to the people and languages of a large part of western Europe. Later in the Middle Ages, when England was no longer considered part of this region (a ‘Medieval Brexit’ in Dorren’s words), Dutch was only used in connection with the mainland, and so people from the Netherlands and Germany were therefore brought together. As Dorren states:

William of Orange is described in our National Anthem as having ‘Duitschen bloed’ (German blood)

William of Orange is described in our National Anthem as having ‘Duitschen bloed’ (German blood)“We did this too: just like the word ‘Dutch’, words like Duutsch, Dietsch, Deutsch and other variants also had that broad meaning. This was more logical than it seems now because the Netherlands and Flanders both belonged to the German Reich. William of Orange is described in our National Anthem as having ‘Duitschen bloed’ (German blood), not because he was born in today’s Germany, but rather because it reinforces his bond with today’s Netherlands.”

The Dutch term ‘Nederlands’ (from the Netherlands) is relatively young and has only formed part of the national vocabulary for around 200 years. Before then words like ‘Duitsch’ and ‘Nederduitsch’ were more commonly used.

Dutch and Germans

It’s actually quite remarkable that the English started calling us Dutch rather than Deutsch

after we became an independent nation during the Eighty Years’ War. Dorren attributes this to the fact that the English traditionally had much more contact with the Dutch than with (the rest of) the Deutsch (Germans). However, the English now had a problem. To be able to differentiate, what would they now call the Deutsch? Eventually the word German was chosen. Dorren writes humorously:

“As a result, the English now no longer had a suitable word for ‘Germanic peoples’ – those gambling, barley-drinking, pagan, fisty cuff types that got the National Socialists so excited. Anyway, that’s not really our problem.”

As a result of this situation, a real word for the language doesn’t really exist in English and it is somewhat laboriously referred to as ‘the German language’.

Foreigners

The confusion between Deutsch and Dutch is especially visible in North America. Initially, the situation was fairly straightforward. It was mainly settlers from the Netherlands who moved to the New World. The English-speaking colonists could simply refer to these sellers as ‘the Dutch’. But the situation became increasingly complicated from the mid-seventeenth century as more and more Germans decided to try their luck in America. Many of them settled in Pennsylvania and called themselves Pennsilfaanisch-Deitsch. The English found this too complicated and translated it to Pennsylvania Dutch, or Dutch for short. And so the word developed into a separate designation for Americans with a German background. Due to the growing stream of German settlers, German was the only foreign language regularly heard for many Americans. As Dorren says:

“They often used the word ‘Dutch’ very sloppily and used it generally to denote a foreigner who speaks something German-ish (such as Swedish), or even simply a (white) foreigner.”

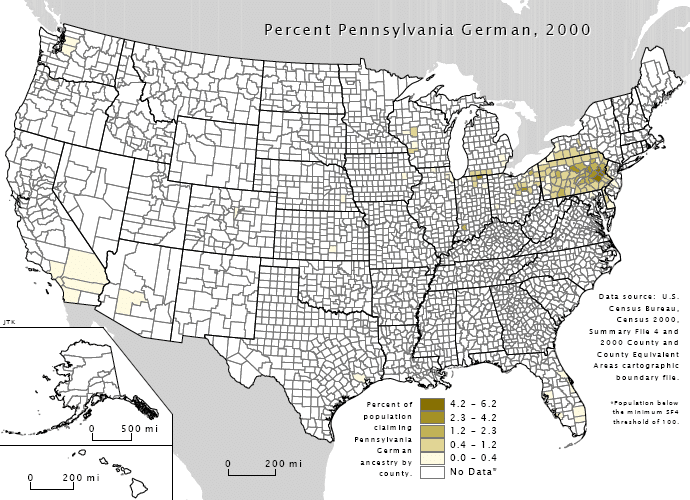

Diagram indicating Pennsylvania Dutch (Pennsylvania German) settlement in the United States

Diagram indicating Pennsylvania Dutch (Pennsylvania German) settlement in the United States© Wikipedia

If you don’t understand what one of these white foreigners is saying, they are said to be speaking ‘Double Dutch’ – a phrase still used today. In other words – gibberish – you can’t make head nor tail of it. Often the expressions in Dorren’s book don’t refer to the Dutch at all. So if the expressions are too negative, we from the Netherlands can always blame the Germans… Due to the continued confusion with Germans, the Dutch government decided in 1934 to stop using the word ‘Dutch’ in international settings. This was probably no coincidence as Hitler had recently seized power in Germany. For that reason, our country doesn’t have ‘Dutch Embassies’ but instead ‘Netherlands Embassies’.

Dutch Courage

One of the best-known expressions involving the word ‘Dutch’ is undoubtedly ‘Dutch courage’. Although folks in Germany don’t mind a drink themselves, this a phrase that really does refer to ‘us Dutchies.’ The phrase goes back to the seventeenth-century naval battles of the Anglo-Dutch wars, which were a matter of control over sea trade routes. In innumerable English pamphlets, the Dutch received all manner of abuse. The pamphlets claimed that the Dutch were terrible drunkards only capable of fighting upon receiving brandy from their captains. This kind of pot-valour was hardly real courage at all. Hence Dutch courage. The expression became so well-known that ‘Dutch Courage’ (in its capitalised form) became synonymous with strong drink, and a gin brand with the very name was even brought to market.

Another few amusing expressions from the book: Dutch Alps (a teasing term for small breasts), Dutch oven (to fart under the bedcovers), Dutch master (a cigar filled with marijuana instead of tobacco), Dutch husband (a sex doll for heterosexual women or homosexual men), Dutch hospitality (terrible hospitality), Dutch Butt Disease (an ugly, fat bottom).

The Dutchionary: the dictionary of everything Dutch is a very entertaining read that you can even learn a thing or two from. In his introduction, Dorren – who previously wrote the internationally well-received language books Lingua and Babel – doesn’t only consider the historical context and meaning of the word ‘Dutch’, but also lavishes attention on the ‘Dutch reputation’, the currency of the expressions, and answers the question of whether the tidal wave of negative expressions has caused any damage to The Netherlands.

Thanks to Dorren’s friendly writing style, this is a bundle that can be read from cover to cover, but is also ideally suited to dipping in and out of.

This article previously appeared in Dutch on historiek.net.