From ‘Gezellig’ to Clean. Why the Dutch No Longer Love Carpets and Chamber Pots

‘Dirty carpet’: the judgement is left on holiday website Booking.com by reviewers writing in Dutch remarkably often. Whether or not accommodation is ‘gezellig’ – snug, warm, sociable – is another important touchstone in such reviews. As is convenience. Clean, gezellig and convenient: this is how many people in the Low Countries would like to see their dwellings. Yet these qualities can be seriously at odds with each other, with the past few centuries seeing cleanliness beat the other two in some fields.

Two places in the home demonstrate this particularly well: floors and toilets. As I will demonstrate, a choice occasionally needed to be made between their gezelligheid and convenience on the one hand, and their cleanliness on the other. In the long term, this led to several historical shifts in Netherlandic domestic life. I would like to speculate that, despite the continued appeal of gezelligheid and convenience, here, the demands of modern hygiene triumph over those other pleasures of daily life.

Carpets

Most members of the nineteenth-century upper and middle classes in this region considered floor carpets an absolute necessity in a good home. The same, by the way, applied to vertical decorations: bare, white walls and beds without curtains did not appeal to their taste. In many other places in Europe, however, carpets were not so self-evident. This evoked critical commentary from Netherlandic visitors. Writer and educationalist Elise van Calcar-Schiotling, for instance, undertook a work journey to Paris in 1858. There, she found the insides of the houses to be quite ongezellig. Even the most well-furnished homes and apartments felt ‘unfinished’, rather than forming a safe and welcoming home. And this is why:

‘I was unsettled most of all by the lack of carpets — the finest, smoothest wood flooring always grims [sic] at me, bare and severe, and it cannot compensate for that finishing touch, that completeness [seclusion] and familiarity which a carpet gives to a room; cherishing like the down in a nest, soft like the lawn in our garden, and harmoniously joining everything together which would otherwise whirl around us incoherently. Carpets belong to the poetry of a gezellig Hollandish home’.

Van Calcar-Schiotling would have appreciated the flooring in this drawing room of the early 1900s

Van Calcar-Schiotling would have appreciated the flooring in this drawing room of the early 1900s© Wikimedia Commons

The twentieth century witnessed a great change, however. The desire for warm and homy carpets was discarded, and replaced by a preference for hard flooring: cold but clean. The hygiene of interior decoration grew in importance in other countries, too, but perhaps nowhere so markedly as in the Low Countries, so that nowadays, Dutch and Flemish tourists complain about the presence of carpets (in foreign bathrooms, most of all), rather than their absence. They now feel at home in freshly scrubbed rooms rather than thickly carpeted ones.

Chamber pots

A parallel development has taken place with respect to another interior-design choice: the location of the lavatory. Before the twentieth century, homes often possessed an outhouse. But in addition, Netherlanders expected to have a chamber pot underneath their bed or under a chair. These bowls, which did not necessarily possess a lid, would not be emptied until the morning. Their owners, in other words, preferred a full pot to nightly visits to the privy.

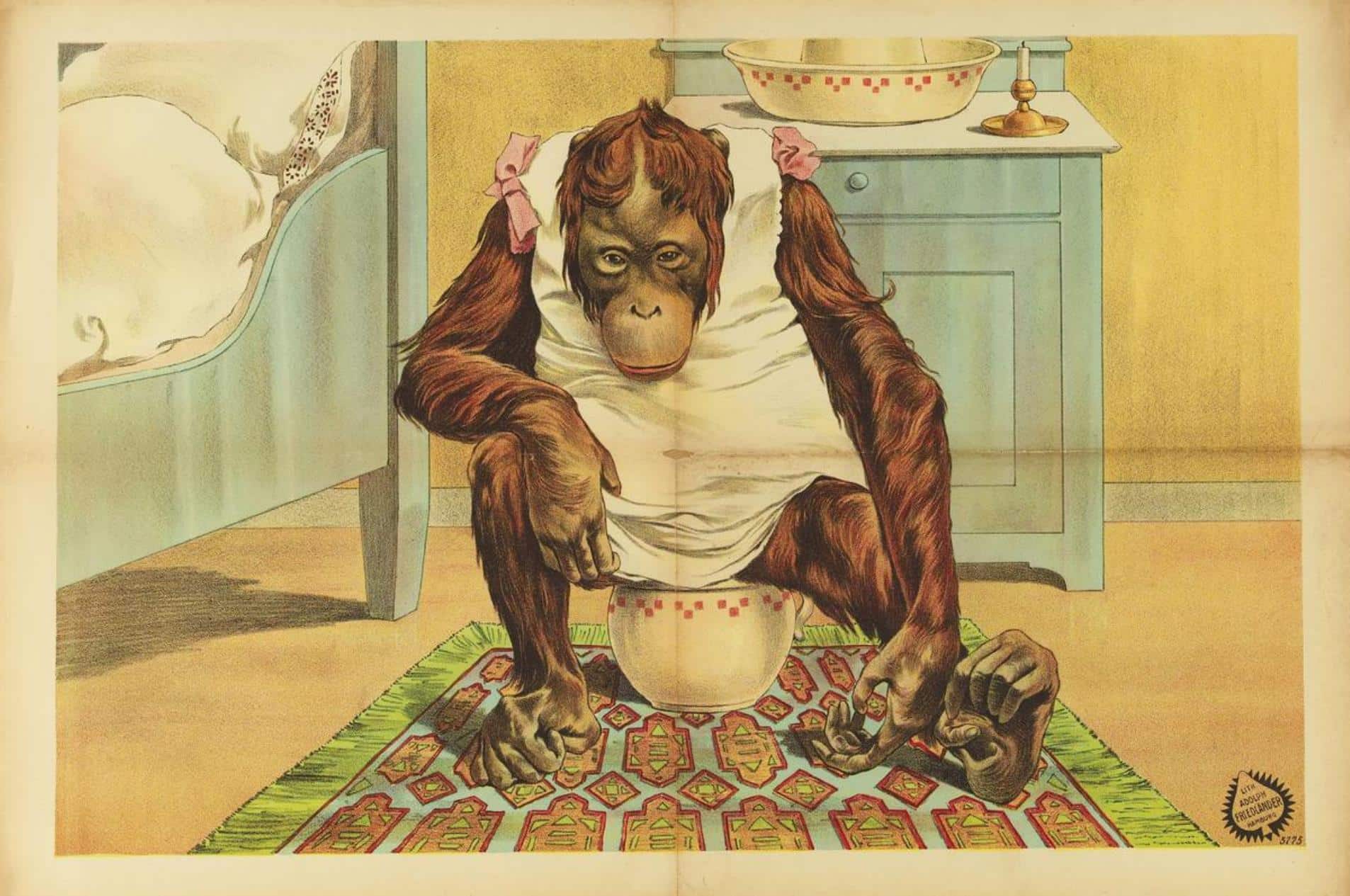

Adolph Friedländer, circus advertisement, 1913

Adolph Friedländer, circus advertisement, 1913© University of Amsterdam

Over the course of the twentieth century, these bedroom articles were increasingly replaced by indoor toilets located elsewhere in the house. Formerly, this convenience had been kept close to bed, which made the few inevitable trips outside the warmth of one’s blankets short in duration and any winter-time ventures into the freezing cold of the rest of the house wholy unnecessary. The gradual removal of the chamber vessel now led to a situation where the disturbed rester had to descend the stairs, which is where the only flushed loo would in many cases be located.

Of course, technological developments played a role in this shift of preferences. The entire house became better heated and insulated, and therefore more bearable on winter nights. The other toilet also slowly moved from the back yard to the house. Outhouse and chamber pot thus merged in the flushed toilet.

Johan Antoni Kauclitz Colizzi, ‘Gard la Tête’, c. 1774-1808

Johan Antoni Kauclitz Colizzi, ‘Gard la Tête’, c. 1774-1808© Rijksmuseum

Yet significantly, the flushed toilet was also cleaner in many respects than the chamber pot. It smelled less at night; it did not need cleaning in the morning; and one did not need to trouble one’s roommates with any throned activities or their results. Perhaps there had also emerged a more general sense that certain acts should simply not be performed in the bedroom at all, since this must be reserved for other (cleaner?) activities. Another cause for the change may have been the disappearance of the idea that smelly sewage vapours, referred to as ‘miasmas’, could by themselves make people ill. A concern about micro-organisms took its place. A fear of foul air was therefore replaced by a fear of touching foul objects, and this may have meant there was no longer much reason to position the loos at a distance from the house, but all the more to be circumspect about handling the inside of the daily-to-be-cleaned pot.

Villeroy & Boch, late-nineteenth-century chamber pot

Villeroy & Boch, late-nineteenth-century chamber pot© Rijksmuseum

All in all, a concern for cleanliness seems to have slowly overtaken an older attachment to comfort here, too. For, granting the importance of the new indoor toilets, the chamber pot would still have been a lot closer and more comfortable than this cold-tiled cubicle, which was often located downstairs, near a draughty front door and in a sometimes literally freezing corridor. For honestly, what post-war dweller of the Low Countries has never wished for a pot right next to their bed in winter?

Across the nineteenth to twentieth centuries, then, cleanliness prevailed over some of the conveniences, warmths and snugnesses of everyday life. By way of conclusion, I would like to suggest that this means some of the earlier regard for the users of carpets and chamber pots made way for a regard for their cleaners. Whereas the nineteenth-century carpet-dweller and chamber-potter were the focal point in the design of these domestic features, by the end of the twentieth century, the person having to maintain these locations – dust the carpets, empty the pots – was provided for better than the earlier days. Perhaps it is no coincidence therefore that these historical shifts in Low Country tastes and technologies were roughly simultaneous to the disappearance of domestic service, and the rise of the unaided housewife.

This article developed some of the themes in Geurts’s book about space and travel in the nineteenth century (Routledge, forthcoming).