From Simple Movement to Mythical Feat, the Uncompromising Theatre of Schwalbe

A crowd continually run laps of a stage, a small group of mime artists busily cycle to keep a stage light on, actors tear one another’s clothes off. Meet the radical, uncompromising theatre of Schwalbe, a collective that sprang from Amsterdam’s mime school.

They have set it out in a contract in black and white: every five years until their deaths, the members of theatre collective Schwalbe will put on at least one performance of their 2008 graduation show, filming the result. After the last Schwalbe member’s death, those decade-bridging recordings will be placed in the hands of a young artist, who can go on to make a time document, a documentary or some other work of art from it, titled Schwalbe Till We Die.

It might seem like a spontaneous, optimistic promise, even if Spaar ze (Spare them, 2008), directed by Lotte van den Berg, were not a physical marathon involving nine mime artists jumping back and forth for an hour to fast techno-beats. Very occasionally there is a brief silence for the artists to consult inaudibly among themselves, a bottle of water to cool off or a tomato to quench their thirst. Only to resume at full volume with their sweaty, pounding club dance. Try repeating that when you’re fifty, sixty or eighty.

Spaar ze (Spare them), 2008

Spaar ze (Spare them), 2008© Stephan van Hesteren

Minimalist stunts

A major feature of this theatre collective, founded in 2009, is their propensity to stretch out a single, simple, energetic movement into a mythical feat, to a level at which that single energetic movement no longer looks pleasant. As in the case of cycling in Schwalbe speelt op eigen kracht (Schwalbe perform on their own, 2010), racing in Schwalbe zoekt massa (Schwalbe is looking for crowds, 2013) or building and demolishing in Schwalbe speelt een tijd (Schwalbe performs a time, 2016). No wonder that the Flemish theatre journalist Evelyne Coussens referred to Schwalbe’s theatrical style, at a performance in 2016 at the Kaaitheater in Brussels, as a form of ‘minimalist stunt’.

In all of Schwalbe’s performances there is a moment at which viewers wonder: are these ‘minimalist stunts’ really theatre? Schwalbe by definition opts never to tell stories or to present characters, dramatic conflicts or scenarios. The performances are almost all radically empty. During Schwalbe speelt een tijd they did assemble and dismantle a set, but one made up of items borrowed from other legendary performances by other Dutch companies. As soon as a set had been cobbled together in workmanlike fashion, ready to come to life with actors playing their parts, the members of Schwalbe quietly resumed deconstruction. They did so from 23.59 at night until 6.00 in the morning. The work of Sisyphus as a meditative ritual. Dragging pieces of the set back and forth all night long – it was up to the viewers to let their imagination run loose, while also being perfectly acceptable to take a nap or fetch refreshments.

Schwalbe speelt een tijd (Schwalbe performs a time), 2016

Schwalbe speelt een tijd (Schwalbe performs a time), 2016© Stephan van Hesteren

Mime with a Dutch twist

The wordless, pared-back movement theatre of Schwalbe fits into a strong mime tradition in Dutch theatre. In the sixties the Netherlands saw the introduction of a style known as mime corporel dramatique, a physically expressive theatre technique developed by French actor Étienne Decroux (1898-1991). Actors such as Will Spoor, Frits Vogels, Jan Bronk and Luc Boyer subsequently laid the foundation for a theatre discipline that was to cause furore as Dutch mime, leading to a shake-up and bringing innovation.

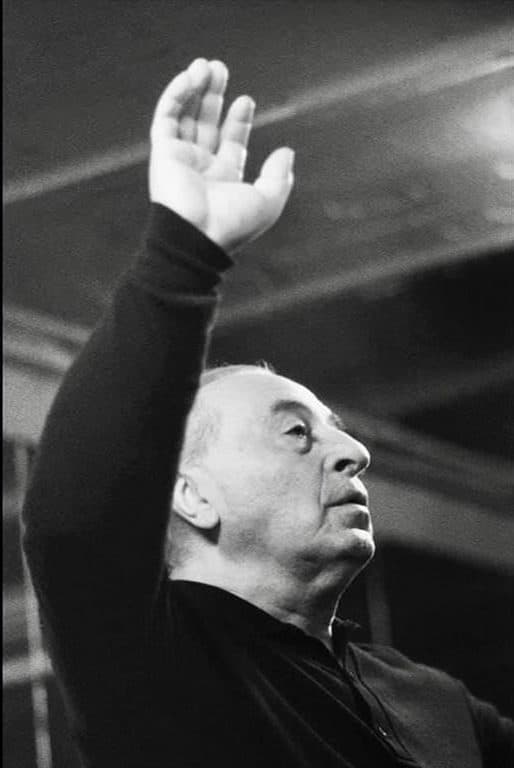

Étienne Decroux (1898-1991)

Étienne Decroux (1898-1991)© Christian Mattis

Instead of a script or character-forming the point of departure, it is the body, an improvisation, an idea, a movement. Those are the tools that make a space visible, for instance, lend a theme a physical form, or create images that are more important than words. Text can play a role, but is subordinate to the body as a means of expression.

This ‘mime corporel with a Dutch twist’ produced innovative groups in the Netherlands such as Carrousel, Bewth, Carver, Nieuw West and Suver Nuver. Since then the vanguard’s torch has been picked up by unique makers such as Jetse Batelaan, Jakop Ahlbom, Boukje Schweigman, Lotte van den Berg and the members of Bambie, each with their own individual signature.

A circling mass of people

In line with the silent, slow theatre of Jetse Batelaan, Boukje Schweigman and Lotte van den Berg, for instance, Schwalbe

has taken a radical course. In the past decade they have produced about one show every year and a half, while allowing members the freedom to perform elsewhere. The collective initially had nine mime artists, all of whom graduated in the same year: Christina Flick, Marie Groothof, Melih Gencboyaci, Hilde Labadie, Floor van Leeuwen, Kimmy Ligtvoet, Bas van Rijnsoever, Ariadna Rubio Lleó and Daan Simons. After that the core of the group temporarily consisted of seven mime artists, briefly even of five, although they’re now back up to six.

In the beginning, the focal point of Schwalbe’s performances was the relationship between individual and group. This came across most strikingly in Schwalbe zoekt massa: seven mime artists run laps of the stage, with 70 to 100 volunteers of all ages in their wake. A regular core of 35 people participated in every city, supplemented with local volunteers. The youngest was 18, the eldest 89.

All the group did was run laps, a silent vortex of human mass. No one made unnecessary movements, not even to brush aside a wisp of hair. Only differences in mobility and glitches in stamina caused slight swells in the syrupy mass. When exhaustion set in, real people began to drop out; viewers would notice more and more idiosyncratic individuals amongst the mob.

Schwalbe zoekt massa (Schwalbe is looking for crowds), 2013

Schwalbe zoekt massa (Schwalbe is looking for crowds), 2013© Arno Bosma and Fanny Hagmeier

The images of the circling mass set off countless associations, from the wondrous euphoria of being absorbed into a crowd, as in a demonstration or concert, to fear of the uncontrolled, destructive force of a herd. In that sense, Schwalbe zoekt massa could be termed a political performance, as described by Elias Canetti in his book Crowds and Power: ‘Suddenly everywhere is black with people and more come streaming from all sides as though streets had only one direction. Most of them do not know what has happened, … but they hurry to be there where most other people are.’

Theatre sports with a deeper layer

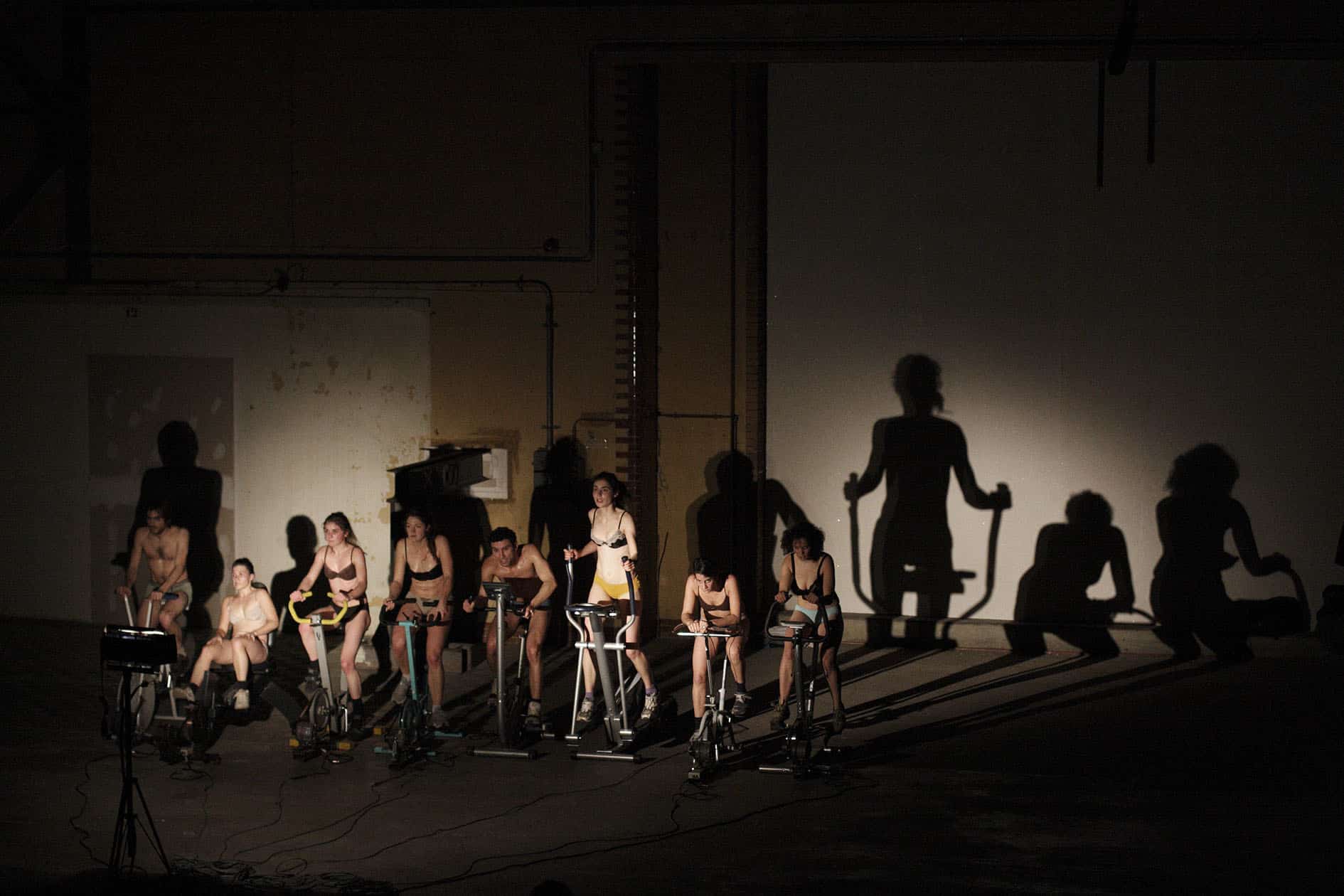

The theatre collective also made a prominent statement in 2010, during Schwalbe speelt op eigen kracht: a CO2-neutral performance in which the group kept a single theatre light on by cycling on second-hand home cycling machines. They pushed themselves right to their physical limits, quite literally in order to stay in view. If they didn’t pedal like people possessed, the light would go out. They had rehearsed without heating, bought the cycling machines from charity shops, and used old printed paper for the flyers. It was here that the name Schwalbe first began to suggest associations with a German brand of bike tyre.

Schwalbe speelt op eigen kracht (Schwalbe perform on their own), 2010

Schwalbe speelt op eigen kracht (Schwalbe perform on their own), 2010© Stephan van Hesteren

You could call it theatre sports with a deeper layer. The same goes for their third production Schwalbe speelt vals (Schwalbe cheats, 2012), directed by the British theatre-maker Tim Etchells, in which they fight, tearing the clothes from each other’s bodies. They seek out the extreme consequence of following through with a physical fight, a competition in which no one sticks to the rules anymore. Hair was pulled, throats were squeezed, and the theatrical dive from football (the notorious Schwalbe) could be observed on a couple of occasions.

How long Schwalbe will continue with this radical, uncompromising theatre, ‘pared back from everything that makes theatre theatre’, remains to be seen. If it’s down to the Schwalbe

members themselves: Till We Die. With Spaar ze as a unique death scene: not a lot of theatre, but a great deal of movement.