From the First Witch to Rubens: Kilkenny’s Flemish Roots

Kilkenny is the most Flemish place in Ireland. The city boasts a fascinating history in which the Flemish have played a crucial role since the 12th century. Their arrival brought technological innovations, flourishing industry and remarkable architecture, all of which made Kilkenny a major centre of trade and craft in the Middle Ages. The Flemish undoubtedly left a lasting impression.

The surname Fleming appears in parts of Scotland and Wales as early as 1150. Today, the name, along with its Irish variants Pléamonn or Pléimeann, is still quite common in the south-east of Leinster, one of the four original provinces of Ireland. And it’s also in Leinster that we find Kilkenny, a lively town with more than 25,000 inhabitants.

Kilkenny flourished between 1207 and 1234 under the leadership of William Marshal, son-in-law of the Norman conqueror Richard de Clare (Strongbow). By the middle of the thirteenth century, Kilkenny was the largest inland town in Ireland and the capital of the Anglo-Norman stronghold on the Emerald Isle. Historians from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries wrote that the Flemish built the original bridges, mills, weirs, dams and other waterworks shortly after they arrived in 1170. It is likely that these were mainly second- or third-generation migrants from Wales.

© Tripadvisor

The influence of the Flemish presence in Kilkenny cannot be underestimated. In a deed from 1339 (the thirteenth year of the reign of Edward III), the area south of Kilkenny Castle is referred to as “in villae Flamingorum Kilkennie”: the town of the Flemish in Kilkenny. The description given by historian John George A. Prim, a nineteenth-century Irish antiquarian, emphasises the importance of this community in Kilkenny. He describes a strongly walled and gated suburb surrounded by towers, called Flemynstown.

Kilkenny castle

Kilkenny castle© Tripadvisor

Archaeological research in 2020, which exposed low, earthen ramparts linked to Flemingstown seemed to confirm the exact location of the Flemish medieval suburb. The ramparts enclose a sunken road running from north to south. Several bodies, which still require further investigation, were found buried in plots to the west of the road. The suburb appears to have covered an area of about ten acres (or a bit more than four hectares). An early fifteenth-century description of the baronies of Kilkenny states that “Flemyngeston” covered an area of eleven acres. This is further confirmed by a description in an old, seventeenth- century parchment roll listing the tenements of the Kilkenny Corporation. The Clarendon Manuscript, which is from the same period, specifically mentions the gateway to the Flemish enclave. This gateway was the closest to the walls of the English quarter and had originally been built by the Flemings on the high ground opposite three watermills belonging to the Lord of Kilkenny.

St. Canice’s Cathedral, Ireland’s best-preserved medieval Cathedral, appearing today very much as it did to the Norman & Gaelic ancestors 800 years ago.

St. Canice’s Cathedral, Ireland’s best-preserved medieval Cathedral, appearing today very much as it did to the Norman & Gaelic ancestors 800 years ago.© Visit Kilkenny

At the stake

The grave slab of Jose Kyteler found at High St. Kilkenny in 1894. His daughter Alice was tried and convicted of witchcraft in 1324.

The grave slab of Jose Kyteler found at High St. Kilkenny in 1894. His daughter Alice was tried and convicted of witchcraft in 1324.© Wikimedia Commons

Among the Flemish families who settled in the city, we find, among others, the Kyteler family. The name is said to be a corruption of De Ketelaere. A certain Robert le Kyteler traded extensively with Flanders at the end of the thirteenth century, but the most notorious scion of the family was Alice. Born around 1263 in Kilkenny, Alice was the only daughter of the Flemish merchant Jose Kyteler. Jose died around 1280 (his gravestone can still be seen today in St Canice’s Cathedral) and Alice inherited his successful wool trading and money-exchange business, which brought her considerable wealth.

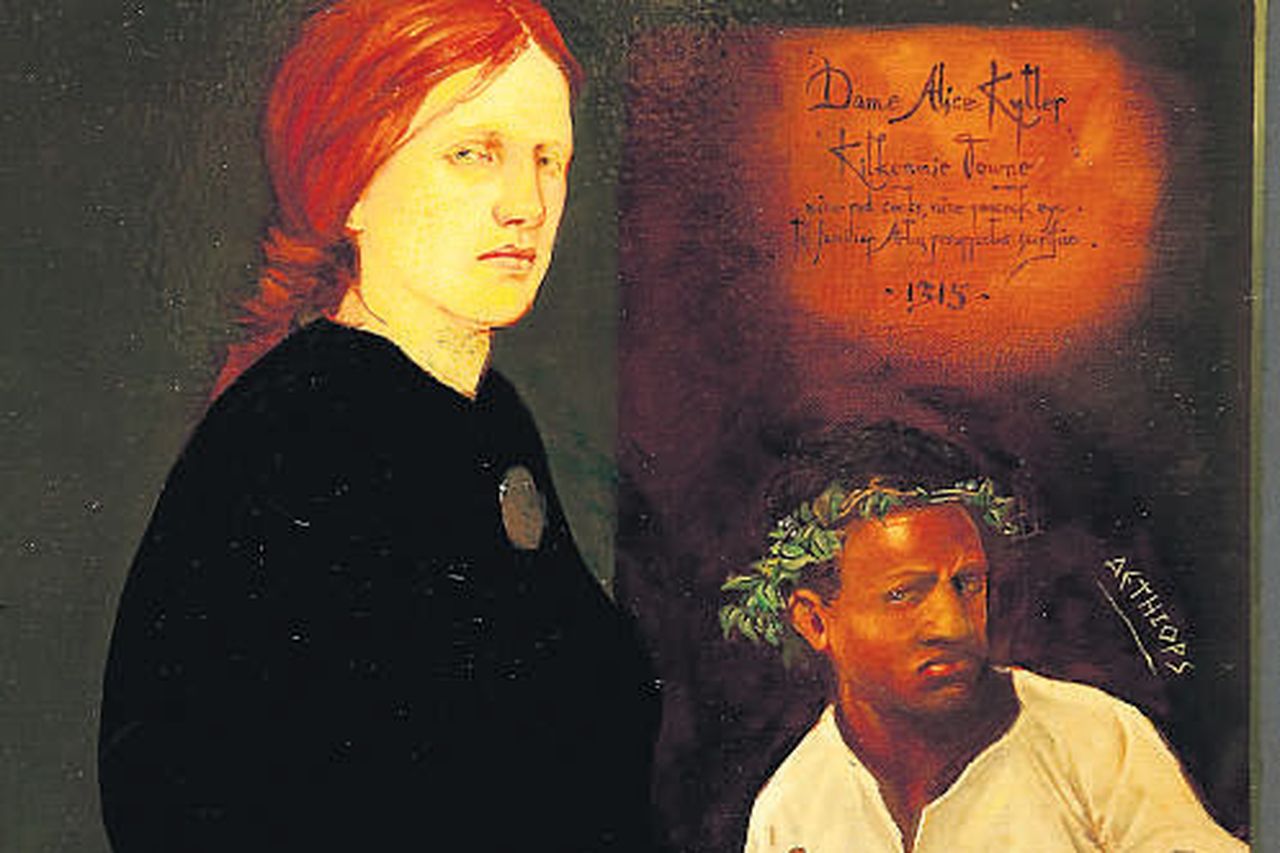

After a first marriage that lasted twenty years, Alice’s next two husbands died in quick succession. When her fourth husband also suddenly fell ill and lost his hair and nails, many people began to wonder… Alice’s stepson Richard de Valle consulted Richard de Ledrede, the Bishop of Ossory. De Ledrede accused Alice of witchcraft and consorting with the devil – accusations that foreshadowed the European witch trials of later centuries. Alice managed to escape but her chambermaid, Petronella of Meath – the first “witch” in Ireland – met a tragic end when she was burned at the stake.

A painting by Paddy Shaw depicts Alice Kyteler, one of the first people in Ireland to be accused of witchcraft.

A painting by Paddy Shaw depicts Alice Kyteler, one of the first people in Ireland to be accused of witchcraft.© Paddy Shaw

A third colony

By 1413, the Flemish enclave seems to have been largely abandoned. According to Prim, the Earls of Ormonde had brought the Flemings to their estate of Dunfert (Danesfort) to farm the land there. The name of the district survived for a while. In municipal rent registers from 1448, the enclave is referred to as “Flemynstown” and “Flemyn’s-Street”. “Ffleming streete” is also mentioned twice in a description of St. Patrick’s parish dating from 1654. Some historical documents of the time refer to the area as “Sraid-na-m-bodach” – the street of the louts, probably because the elites looked down on the earlier inhabitants, who were mostly manual labourers.

It would not be long before the Flemish were once again established in the inner city of Kilkenny. Peter Butler, the 8th Earl of Ormonde and his wife, Countess Margaret of Kildare, brought about a Flemish renaissance. Margaret’s patronage of the arts led to a cultural revival in the counties of Tipperary and Kilkenny. Together with her husband, Margaret established a Flemish textile mill in Kilkenny around 1525 and invited “500 Walloon Protestant families to come to Ireland”. “Walloon”, in this case, usually refers to inhabitants of French Flanders. These were linen and wool weavers, fullers, cooks and brewers. Although some of these immigrants may have found accommodation in the shadow of the castle, in old Flemingstown, it seems more likely that they were accommodated in Kilkenny’s Hightown.

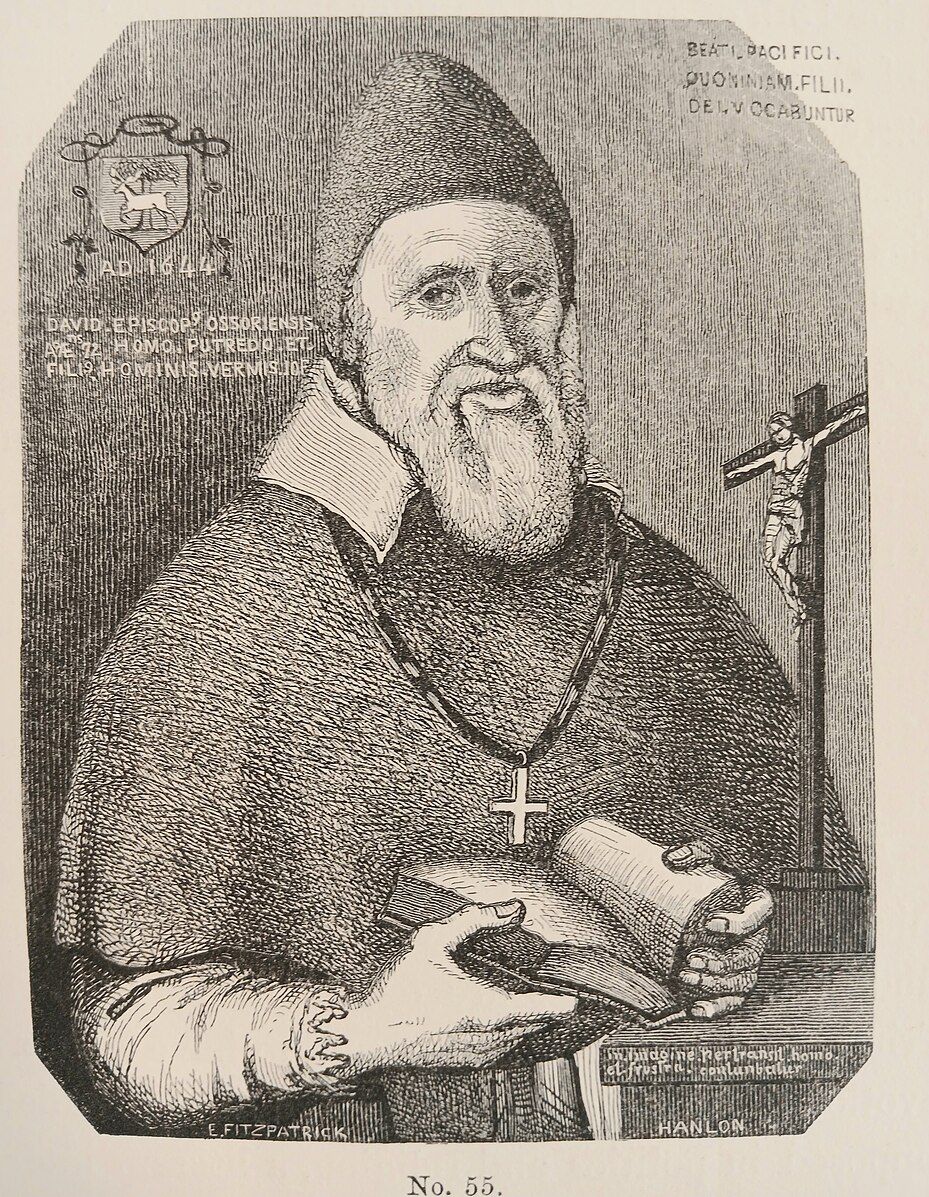

According to Bishop David Rothe, the influence of the Flemish in Kilkenny was not to be underestimated.

According to Bishop David Rothe, the influence of the Flemish in Kilkenny was not to be underestimated.© Wikimedia Commons

Bishop David Rothe, writing around 1625, described the former Flemingstown as being situated “in the vicinity of the castle”, with paved streets, plots of land and a “marble gate”. Today, Kilkenny is still known as ‘the marble city’. The marble in question, however, is a black-blue stone, comparable to the blue limestone of Tournai. According to Rothe, the influence of the Flemish was not to be underestimated:

“These two peoples, namely the Irish and the English, had settled in the place, and to them was added, as it were, a third colony, consisting of Flemish craftsmen and professionals, especially fullers, bakers and brewers, and those employed in the linen and woolen industries. Invited by the former inhabitants and residents, they built on their arrival a strongly fortified settlement near the castle to protect themselves from plunderers and robbers; and this place, which they occupied, was called after them Fleming’s Town or Flemish Town, as appears from many old charters and deeds. From the stone pavements and other indications there, we may gather how extensive these suburbs were, although they are now divided and intersected by dikes and ditches for the protection of grain and vegetable crops.”

Flemish people bring “benefits and prosperity”

The seventeenth century was a turbulent time in Ireland. The Irish Catholic Confederation (1642 and 1652) was a period of Irish Catholic self-government. Formed after the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and comprising Catholic aristocrats, gentry, clergy and military leaders, the Confederation controlled nearly two-thirds of Ireland from its base in Kilkenny. But even during this unsettled period, Flemings continued to move to Kilkenny and the surrounding area. Luke Wadding, an Irish Franciscan and historian, wrote to Pope Urban VIII on behalf of the Confederation of Kilkenny (as the Irish Catholic separatists were also known), saying that the “many Dutch and Flemish Catholics” who settled in Waterford “brought much benefit and prosperity to the said town by their trade.” By the early seventeenth century, the Flemings wanted to build their own church there.

In late 1642, agents of the Kilkenny Confederacy in Flanders issued “at least twenty blank letters of marque to captains of foreign frigates who were prepared to patrol Irish waters in return for freedom to roam the seas”. Indeed, by the mid-seventeenth century, many pirates had already established themselves in the south-east of Ireland, around Waterford and Wexford. They regularly attacked merchant ships sailing between Kilkenny and Antwerp. Among the Flemings involved in privateering in the city’s harbour were Joseph Constant, captain of the St Peter; Antonio Vandezipen, whose company was based in Waterford; Daniel Van Vooren, commander of the St John; and Francis Oliver, captain of the Patrick.

The last wave

After the rebellion of 1641 was crushed, a third wave of Flemish settlers settled in Kilkenny when, during the British Restoration of the monarchy (1660), James, the first Duke of Ormond, brought some four hundred Flemish craftsmen to Dublin, Kilkenny, Carrick-on-Suir and Clonmel. They were given shelter, looms and raw materials from which they developed a considerable trade in rope, sailcloth and linen fabrication. With the Irish Reformation at the end of the seventeenth century, Flemish tapestries also began to appear in Kilkenny. An inventory of Ormond tapestries from 1684 mentions no fewer than 130 pieces.

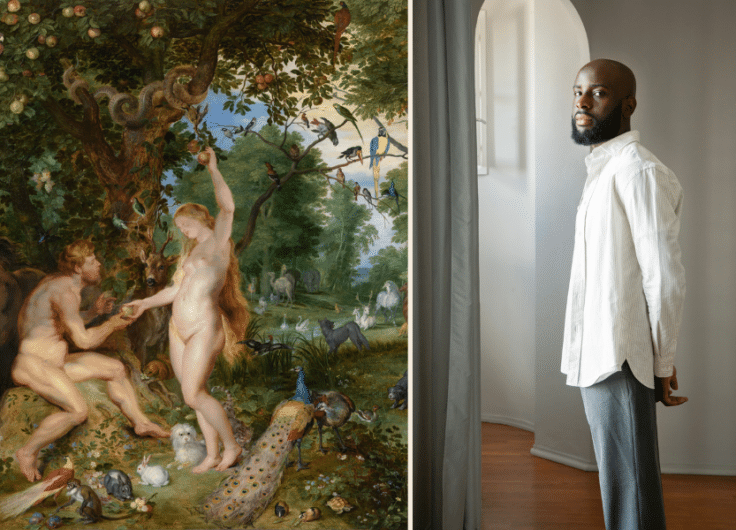

Four tapestries, designed by Peter Paul Rubens, can be seen in Kilkenny Castle.

Four tapestries, designed by Peter Paul Rubens, can be seen in Kilkenny Castle.© Bruno Iserbyt

Today, four pieces from a series of seven, designed by Peter Paul Rubens in the early seventeenth century and depicting the story of Decius, a Roman general, can be seen in Kilkenny Castle. Rubens used “cartoons” – patterns followed by specialised weavers and turned into tapestries – to draft the original artwork. The masterful craftsmanship of these tapestries is attributed to the studio of Jan Raes in Brussels.

The medieval streets of modern-day Kilkenny show a great deal of Flemish influence.

The medieval streets of modern-day Kilkenny show a great deal of Flemish influence.© Instagram / Villagesmypassion

That the medieval streets of modern-day Kilkenny show a great deal of Flemish influence is beyond dispute. But probably the most important influence is related to the most recent mention of Flemish people. In 1663, a letter to the Duchess of Ormond mentions several Flemish citizens: “There are about twelve acres of land between Ormond’s Leix [i.e. meadows] and the road to the marble quarry, which formerly belonged to several citizens, from which his highness has a levy.” The expropriation of the land made possible the creation of the parkland to the east of the castle, which to this day remains one of the most picturesque spots in Kilkenny.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.