On a visit to the Flemish city of Genk, Derek Blyth discovers restored coal mines, cosmopolitan chickens and one of the world’s great love songs.

Marina, Marina, Marina.

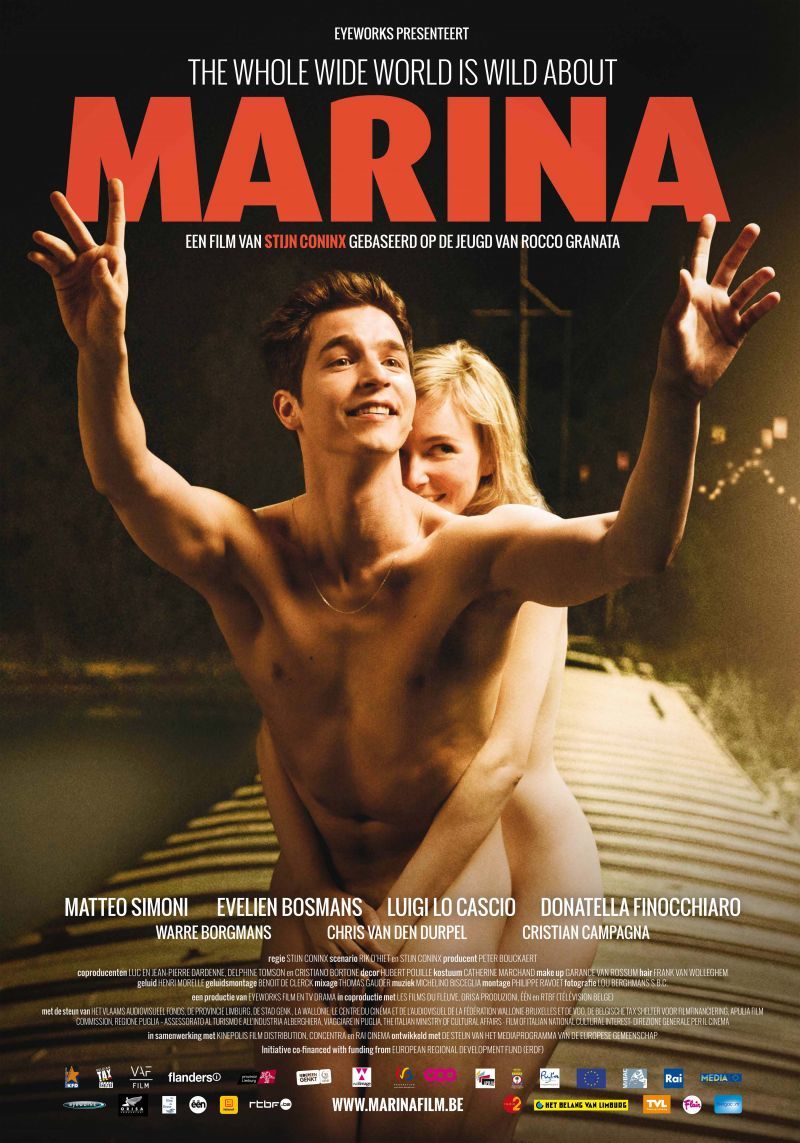

On a slow train to Genk, I can’t get an old song out of my head. It was composed by an Italian miner’s son called Rocco Granata who grew up in Genk in the 1950s. He wrote a simple love song that became a global hit. His unlikely story was turned into a 2013 film by the Flemish director Stijn Coninx.

The unlikely story of Italian miner’s son Rocco Granata was turned into a 2013 film by the Flemish director Stijn Coninx.

The unlikely story of Italian miner’s son Rocco Granata was turned into a 2013 film by the Flemish director Stijn Coninx.Mi sono innamorato di Marina, the song begins. More than 50 years after its release, it still feels fresh and optimistic. A lot of older Belgian women are apparently called Marina because their parents loved the song. And yet it comes from a gritty coal mining town that at the time was surrounded by winding towers and slag heaps.

I stepped off the train with a plan. I would go in search of Rocco Granata’s roots. The story began when Rocco, aged 21, was recording a song with his band. The song was called Manuela. He realised he needed a B-side to make a single, so he taped an improvised song called Marina while the rest of the band was out of the studio. But the record companies weren’t interested in an Italian nobody who worked as a mechanic in a Vespa Garage. Rocco had to raise the funds himself to produce the first 300 copies and then try to sell them in local record shops. His first customer was Betty Peeters who ran a record store and discobar at Vennestraat 199. She took 25 copies.

So Betty’s was going to be my first stop. I rented a bike to get there. It seemed the right thing to do in Genk. It’s in Limburg, the province that promotes itself as a cycling destination. And most of the places I had to visit were out on the edge of town. Too far to walk, but perfect by bike.

Sadly, Betty’s has gone. A short text on a glass door recalled Betty’s brief moment of fame. The store has been replaced by a wine bar with a modern glass façade. But then I noticed that the old brick building had been preserved behind the glass. In memory of Betty, I found out later.

Rocco Granata

Rocco Granata© City of Genk

The B-song rose in the charts. Suddenly, record companies were turning up on the doorstep of the Granata family home with contracts to sign. Marina went on to sell more than 100 million copies. Rocco was invited to New York to perform in Carnegie Hall. According to John F Kennedy’s private cook, the President liked to whistle Rocco’s catchy tune.

The young Italian from Genk had picked the right career path. The mines where his father’s generation had found work were starting to close down in the mid-1960s. It was a huge blow for thousands of families who had migrated north in search of work.

The city realised it had to come up with a Plan B. In 1962, the Ford car company

was persuaded to build a large factory outside Genk. The new American factory seemed like a safe bet. But the good times came to an end in 2014 when Ford announced that it was closing the Genk plant, with the loss of some 4,000 jobs.

Ford Genk employed 4,000 people.

Ford Genk employed 4,000 people.© Johnny Harsch / archives Emile Van Dorenmuseum, Geheugen van Genk

On 18 December 2014, the church bells in Genk rang out at midday. The city mayor had called for a ‘moment of noise’ on the day the factory shut down, with workers and locals yelling, sounding car horns, ringing bicycle bells and banging pots and pans. As the last Ford Mondeo came off the line, it seemed like the end of the road for the struggling Limburg city.

But no. Unlike many former mining towns across the world, Genk had a plan. If the Ford factory was Plan B, the city still had a Plan C. The C stood for culture, I discovered later that day when I visited the former Winterslag coal mine, now rebranded C-mine.

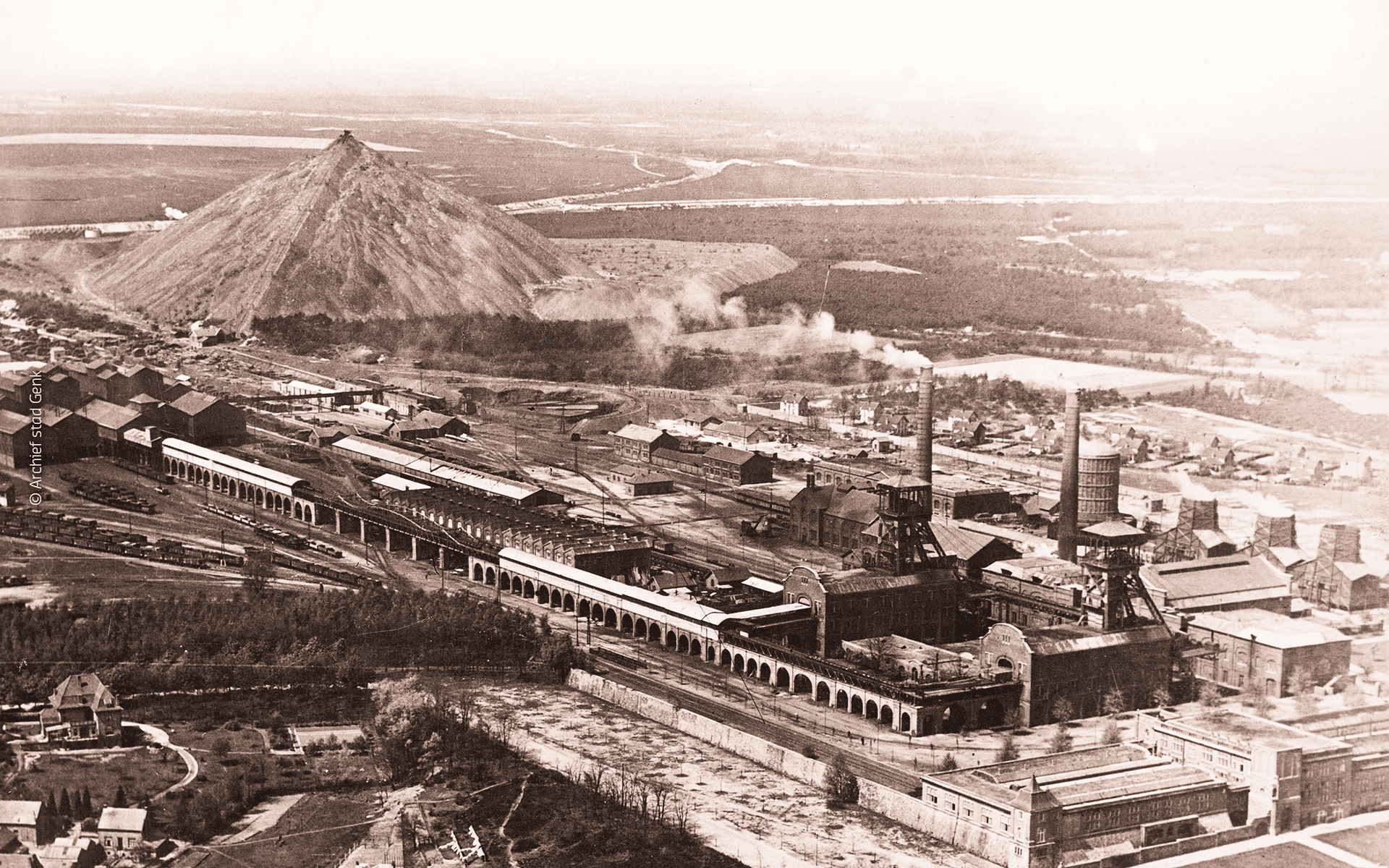

A solemn stone memorial stands outside the mine. ‘On 28 July 1914,’ it reads, ‘The first lump of coal in the Kempen seam was dug in this spot in Winterslag under the visionary owner Baron Coppée.’

On 28 July 1914, the first lump of coal in the Kempen seam was dug in Winterslag.

On 28 July 1914, the first lump of coal in the Kempen seam was dug in Winterslag.© archives Emile Van Dorenmuseum, Geheugen van Genk

It was hardly the most promising moment to begin the industrialisation of Genk. Just a week later, the German army crossed the border into Belgium. The mine only became operational in 1917, when its coal was used to fire up the German war effort.

The Winterslag mine only became operational in 1917.

The Winterslag mine only became operational in 1917.© City archives Genk

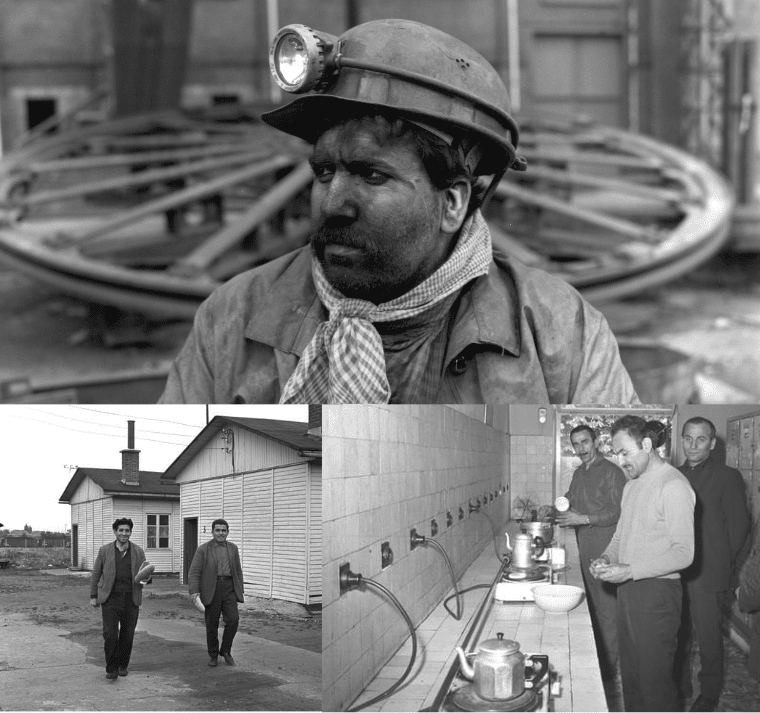

The Limburg village turned into a boom town as several other mines opened in the region. The three Genk coal mines eventually employed more than 18,000 workers, among them migrants who moved here after the Second World War from Italy, Greece, Portugal, Morocco and Turkey.

Men from all over came to Genk and the Kempen region to work as miners.

Men from all over came to Genk and the Kempen region to work as miners.© Johnny Harsch / archives Emile Van Dorenmuseum, Geheugen van Genk

But the industry started to decline in the 1960s. The Winterslag mine shut down in 1988, leaving behind an abandoned site. Across the North Sea in England, the government was busy demolishing former mines to create new sites for industry. And closer to home, the Dutch coalmines were demolished in an attempt to transform the landscape back from ‘black’ to green. But Limburg adopted a different approach. Rather than tear it all down, they would give some buildings a new purpose. 11 of the 45 original buildings of the Winterslag mine were listed as a protected monument in 1993. The rest was demolished.

The huge industrial site has now been turned into the vibrant creative hotspot, C-mine. The impressive old mine buildings from 1917 have been preserved, including an engine house full of oily machinery, the lamp room and the managers’ building. Looming over the site, the two skeletal shaft trestles with their enormous wheels rise above the rooftops as a reminder of Genk’s past.

Two skeletal shaft trestles with their enormous wheels rise above the rooftops as a reminder of Genk’s past.

Two skeletal shaft trestles with their enormous wheels rise above the rooftops as a reminder of Genk’s past.© C-mine

The complex now incorporates offices, a brasserie and a tourist office. It also has a gallery space and a modern steel maze in the courtyard outside. You can wander around the vast machine hall with its beautiful tiled floor, elegant iron staircases and ancient control panels.

Inside the Energy Building on the C-mine site.

Inside the Energy Building on the C-mine site.© C-mine

It’s even possible to go down below the ground. The C-mine Expeditie is a visitor attraction that takes you through brick ventilation tunnels where you are confronted with strange noises, visual special effects and even the smell of the mines. The experience ends with a stiff climb up a spiral staircase to the top of the winding tower, some 60 metres above the ground.

The C-mine Expeditie takes you to a depth of six meters, where the history of the miners begins.

The C-mine Expeditie takes you to a depth of six meters, where the history of the miners begins.© C-mine

It’s not a museum, an information panel insists. They don’t want it to be a place of memory. Or not only that. There is a cinema on the site (located in the Lamp House where the miners picked up their torches). There is also an art school next to the mine, along with tech companies, a creche and the workshop of the internationally renowned ceramist Piet Stockmans. The C-mine programme for the year is a thick 120-page booklet filled with exhibitions, performances and talks.

Not a museum then. But the past is still remembered in old photographs displayed across the site. They show the machine rooms, the equipment and the faces of the miners who spent their working lives below ground. The first lump of coal dug out of the Kempen ground is displayed in a glass case.

It was tough work. But maybe not as grim as mines in other regions. The buildings were designed by the Brussels architect Adrien Blomme. He had spent the First World War in England where he studied the design of English garden cities. He drew on this style in his designs for several mine workers communities including the Winterslag garden city, where the miners’ families lived in attractive houses with generous gardens. The children played in tree-lined streets and went to decent schools.

The miners’ families lived in attractive houses with generous gardens.

The miners’ families lived in attractive houses with generous gardens.© Johnny Harsch / archives Emile Van Dorenmuseum, Geheugen van Genk

The tourist office at C-mine offers a stack of brochures packed with inspiring ideas for spending a day in Genk, including ten places where you could go for a picnic. Many of the ideas involve cycle routes, including one that links Genk’s three mine sites using the knooppunten system of numbered cycle points.

Perfect, I thought. The system was invented by an engineer who worked in the Limburg mines called Hugo Bollen. Inspired by the emergency escape routes used by the miners, he created a simple navigation system based on numbered points.

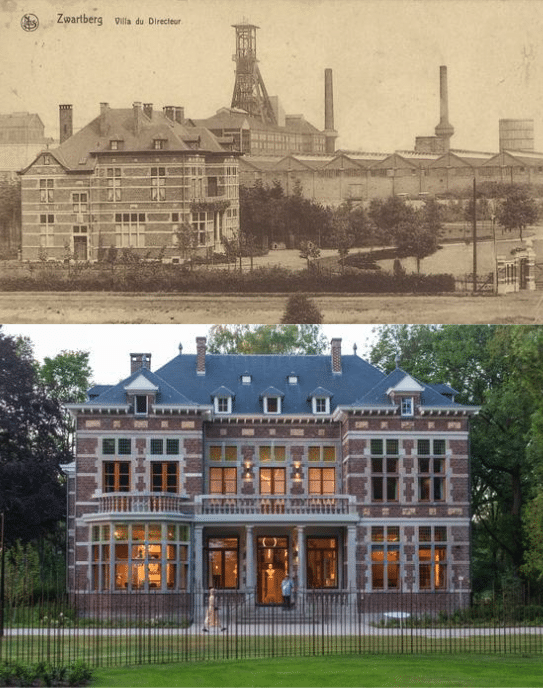

I set off to the next mine site, a 15 minutes ride away. The mine used to be called Zwartberg. But the name has gone, as have most of the buildings, leaving just the grand mansion once occupied by the mine director.

The grand mansion of the director is the only remaining building of the Zwartberg mine.

The grand mansion of the director is the only remaining building of the Zwartberg mine.© archives Emile Van Dorenmuseum, Geheugen van Genk / © Koen Vanmechelen, City of Genk, photo by Tony van Galen

After the mine closed down, the buildings were demolished. Someone opened a café on the site with a caged lion in the garden. It grew into a private zoo with more than 1,000 animals. But the zoo was badly run and had to close in 1998. The Belgian artist Koen Vanmechelen, known for his Cosmopolitan Chicken breeding project, took over the abandoned wilderness to create an experimental laboratory called LABIOMISTA.

The Ark, entrance building of LABIOMISTA

The Ark, entrance building of LABIOMISTA© Koen Vanmechelen, 2019, photo by Enrico Cano

He commissioned the Italian architect Mario Botta to design a bold black entrance pavilion known as the Ark. It leads to the former director’s home where Vanmechelen now displays art that reflects his obsessive interest in chickens and other animals.

T-Rex by Koen Vanmechelen, one of many sculptures in LABIOMISTA.

T-Rex by Koen Vanmechelen, one of many sculptures in LABIOMISTA.© Koen Vanmechelen, photo by Kris Vervaeke

The next building is a vast greenhouse. Beyond here, a wild area has been turned into a breeding ground for animals including llamas, ostriches and dromedaries. In a field across the street, Vanmechelen has developed another project called Nomadland. Here he created a temporary settlement made up of tents, wooden stages and painted caravans. The site is quiet during the week, but it gets lively on summer weekends when organic and sustainable food is served while tame dromedaries and other animals wander around.

I got back on the bike. Another 15-minute ride to the next knooppunt. The route was more varied than I had expected. It passed through woods, across abandoned railway tracks and next to a wild moor. Along the way, I glimpsed huge villas built for the mine managers and massive Art Deco brick churches funded by the owners. Finally, I spotted another tall winding tower. It belonged to the Waterschei coal mine, which closed in 1987. Now rebranded Thor Park.

The mine once employed 7,000 people. Many came from Turkey and Morocco, including the father of Zuhal Demir, who now sits in the Flemish government as minister for justice, environment, energy and tourism. Born in Genk, she went to the local school, graduated from Leuven university, and eventually became one of the most influential politicians in Flanders.

Thor Central

Thor Central© City of Genk

Thor Central, the huge administrative building that also housed the bathing rooms and lamp rooms is still standing. It is rather empty compared to C-mine. But impressive all the same. A staircase leads up to two enormous halls with dark mustard-coloured walls, elegant ironwork and old photographs of miners.

They are working on a different plan here. It involves small businesses dedicated to green energy, along with a tech campus and an incubator. Sorry, Incubathor. And the foundations have been laid down for a large new research campus dedicated to smart manufacturing companies. Called FacThory.

The site of the old Waterschei coal mine is turned into Thor Park, a hub for small businesses, a tech campus and an incubator.

The site of the old Waterschei coal mine is turned into Thor Park, a hub for small businesses, a tech campus and an incubator.© City of Genk

I was beginning to understand where Genk was heading. The city had gone from coal to cars to culture. And now it was focusing on green technology. It even has a new slogan, which plays on the words Genk and denk (think). Iedereen Genkt, it says. Genkly does it, I wanted to say.

The mine site now forms the entrance to a vast natural park, the Hoge Kempen National Park. There are dozens of walking trails and cycle routes that head off into the wild. One meandering route leads to the top of a spoil heap planted with trees. The path was too bumpy for a bike, so I hiked up the narrow path. The route was marked out with strange stone cairns known as Steenmannetjes, or little stone men.

The Hoge Kempen National Park is a nature reserve where more than 12,000 ha of forest and heathland are managed and protected.

The Hoge Kempen National Park is a nature reserve where more than 12,000 ha of forest and heathland are managed and protected.© City of Genk

As I looked down on Thor Park, I realised Genk was not at all what I had expected. This wasn’t a depressed industrial city where all the jobs had gone. It was a vibrant, dynamic place that was looking forward to the future. In just over a century, it had gone from dirty coal to polluting petrol cars to green tech. And if the green tech didn’t work out, it would try something else.

From the summit, I could look down on the Racing Genk stadium, where the local team plays. I learned from a fan that the club was formed in 1988 from the merger of Waterschei Thor and KFC Winterslag. One team for each coal mine. The stadium now has an interactive football experience cleverly called Goalmine.

I headed back into the centre along Stalenstraat. Vallei van Werelden, a sign announced at the start of the street. Valley of the Worlds, literally. It sounded like a place in a sci-fi novel, but looked like an ordinary Belgian shopping street. Until I looked more closely at the shops. A Moroccan butcher, a Greek restaurant, and a Turkish hairdresser. I eventually got it.

The Stalenstraat is nicknamed Valley of the Worlds because of the many different nationalities living there.

The Stalenstraat is nicknamed Valley of the Worlds because of the many different nationalities living there.© City of Genk

The mine workers had migrated to Genk from Greece, Turkey, Portugal, Morocco, Spain and Italy. They turned a Limburg village into one of the most multicultural cities in the Low Countries. Each nationality added a layer to the local culture. The Greeks introduced sweet pastries, the Moroccans brought couscous, and the Turks added sweet baklavas to the mix. The modest Stalenstraat neatly reflects the city’s cosmopolitan identity. You can buy North African carpets, big cooking pots for boiling pasta, and cheap phones to call back home.

The Stalenstraat reflects the city’s cosmopolitan identity.

The Stalenstraat reflects the city’s cosmopolitan identity.© City of Genk

Back in the city centre, I was expecting it to be depressed, given Genk’s history of industrial decline. But I found instead a lively cluster of pedestrian streets and squares with busy shops and stylish cafes.

The biggest surprise was the city library. Designed by the French architect Claude Vasconi, it’s a bright, generous space with four stepped levels surrounding a vast atrium. The building includes touches of warmth, including a giant chess set, a grand piano and a colourful dragon. It also displays a collection of contemporary art, including an installation by the Belgian artist Denmark titled Brandhout

(Kindling). The work is made from dozens of glossy magazines rolled around wooden sticks.

The city library of Genk is designed by the French architect Claude Vascon.

The city library of Genk is designed by the French architect Claude Vascon.© City of Genk

I was staying in the city centre at the Carbon Hotel. Carbon, because of coal. The hotel rooms were dark, muted, as if everything was covered in a thin layer of coal dust. As I read through the heap of brochures I had accumulated, I came across a city project that encouraged locals to propose ideas to improve the city. There was no shortage of inspiring suggestions. My favourite was a proposal to create ‘The Longest Spaghetti’. Measuring more than three kilometres, the spaghetti strand would wind through the streets of Genk as a way of bringing together all the citizens.

Iedereen Genkt, I thought.

***

The next morning, I set off on a cycle trail through the forests around Genk. I was heading for an attraction near Bokrijk Open-Air Museum called Fietsen door het water (cycle through the water). It takes cyclists across a lake on a metal bridge sunk below the water. It’s one of several smart projects by Limburg province to make cycling a little more fun.

Cycle through the water near Bokrijk Open-Air Museum

Cycle through the water near Bokrijk Open-Air Museum© City of Genk

Back in Genk, I crossed a beautiful cycle bridge over the busy West ring road. It was built in 2014 to connect two districts separated by a busy four-lane highway. The white steel structure takes cyclists up in a series of gentle loops, almost like a roller coaster.

It was time for lunch. ‘You have to look at Vennestraat,’ a Flemish friend told me. ‘They call it the straat van de zintuigen – the street of the senses.’ It was not far from C-mine. I had already been there looking for Betty’s record shop. At first, it looked like a typical Flemish shopping street. But then I noticed a Turkish barbershop, an Italian delicatessen, and a Spanish tapas bar.

I learned later that someone was growing olive trees in a back garden on Vennestraat. And I also found out that Betty’s husband had planted a vineyard in the garden behind the famous record store.

Aerial view of an illuminated Vennestraat. A mine shaft (left) and slag heaps (right) can be seen on the horizon.

Aerial view of an illuminated Vennestraat. A mine shaft (left) and slag heaps (right) can be seen on the horizon.© City of Genk

I had been told De Griekse Frituur was the place to eat. It was hidden away at the dead end of Vennestraat next to the busy ring road. Nothing special, you might be thinking. But this Greek restaurant was one of the friendliest places I have eaten at in Belgium.

It goes back to 1974 when Nico and Anna opened a simple Greek restaurant near the Winterslag mine. It is now run by their grandchildren who have kept alive the warm Greek welcome. The interior is decorated with family photos, plastic flowers hung from lamps and odd ornaments. The menu is simple Greek street food. I asked for calamari with fries and homemade sauce. It came served on newspaper.

Aerial view of the city centre of Genk

Aerial view of the city centre of Genk© City of Genk

At the end of the trip, I was hoping for a souvenir to take home from Genk. Unfortunately, I was too late for the tomatoes. Every year, at the end of the summer, a truck arrives in Genk loaded with crates of fresh tomatoes from Southern Italy. They are imported by Manuela Da Rotilio to sell to Italians in Genk. Everyone agrees you need Italian tomatoes to make passata tomato sauce. As soon as they hear the news, local families with Italian roots head to a hangar in the huge Limburghal. Eccoli qui! They are here!

The Genkse Koekjes (Genk biscuits) reflect the city’s multicultural identity.

The Genkse Koekjes (Genk biscuits) reflect the city’s multicultural identity.© City of Genk

But I had another idea. Later in the afternoon, I stopped at Bakkerij Goiris in Vennestraat. The baker has decided to create a box of Genkse Koekjes (Genk biscuits) to reflect the city’s multicultural identity. A Turkish friend provided a recipe for nutty Findikli biscuits, a chef in Naples set out the steps for making dry Cantuccini biscuits, and a Greek friend lent him an old cookbook containing a recipe for the crescent-shaped biscuit Kourabiéthes. The selection also contains sugary Polish Pierniki and Belgian Palet de Dames smothered in chocolate.

It was time to leave with my box of Genkse Koekjes. At the end of two days, I had fallen in love with Genk. It struck me as a relaxed, friendly place. Maybe because of all the Italians who brought a touch of la dolce vita. But also because of the Greeks, the Turks, and other nationalities.

I was hoping to hear Marina being played somewhere in Genk before I left. Maybe in Gepetto’s cafe in Vennestraat. Or across the street in Gelateria Principe. How about on the terrace of the cafe Circolo Sardo Grazia Deledda where retired miners from Sardinia like to meet up? Come on, Genk. It should be your anthem.

Never mind. I could listen to it on the train, on headphones.

Mi sono innamorato di Genk. I am in love with Genk, I wanted to sing as the train pulled out of the station.

This article was realised with the support of the Flemish Government.