Here Is Why We Should Continue to Cherish Multatuli

The unveiling of a commemorative stone on 17 February 2020 in the Amsterdam Nieuwe Kerk marked the start of the Multatuli year. Soon you will be able to walk across that stone yourself. On the stone, artist Jeroen Henneman depicted a mill and a palm tree. He also worked an emerald into the bluestone and opted to include the first line of Multatuli’s masterpiece Max Havelaar, ‘I am a coffee broker and I live at Number 37 Lauriergracht.’ Many considered this an odd choice. Most had preferred another quote. ‘Jesus began with fishermen, I start with girls.’ I myself might have opted for, ‘I cannot go with anyone. People should have come with me.’

Author Arnon Grunberg talked about the truth being at stake in Multatuli’s oeuvre, a body of work that is continually self-sabotaging: ‘His work urges us to be more critical, his polemic attitude reminds us of the fact that cowardice is any intellectual’s worst enemy, and the author calls on both writer and reader to never forget that the commandment of truth consists of ambiguity and double entendres, yet should always remain a commandment. He beseeches us not to close our eyes to half-heartedness – which is all too human –, for those who close their eyes to that are sacrificing truth for steak. This is – once again – where his greatness lies.’

Grunberg concluded with these words: ‘But above all this, there is his sparkling sense of humour; his oeuvre is permeated with an ingenious and ambiguous self-relativism, and yes, then there is also his style, without which this was all doomed to fail: “Those who disapprove, I disapprove of”.’

The unveiling of the commemorative stone by King William Alexander

The unveiling of the commemorative stone by King William AlexanderActor Thom Hoffman played the role of Max Havelaar and of course addressed William III (‘To thee I dedicate my book’), who was present in the Nieuwe Kerk in the guise of William Alexander. Similar to William, the king did not actually reply. Except for afterwards, when he admitted having initially read the book reluctantly, as it was a mandatory school assignment, but had later re-read it in one go over the course of a sleepless night, and had come to appreciate it.

Non-conformism and rebellion

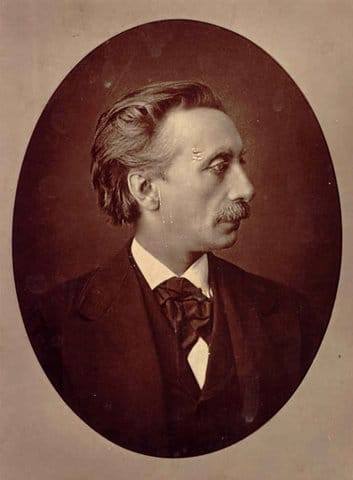

The best possible tribute to Eduard Douwes Dekker (1820-1887) continues to be Willem Elsschot’s: ‘For our linguistic region, Multatuli has been a true Prometheus. Rejected by every ruler, he has eaten his bread in exile, but, undespairingly, has held high the torch of non-conformism and rebellion. From his ashes, the entire contemporary Dutch literature has risen. His cult is all of our solemn duties.’

Max Havelaar

Max HavelaarMultatuli wrote his Max Havelaar – a charge against the treatment of the locals in Dutch India by both Dutch and Indian governors – in less than a month (September-October 1859) in a boarding house called Au Prince Belge in the Brussels Bergstraat, while on the run for his creditors. At the time, Dekker was staying in what his second wife Mimi termed ‘in essence an alehouse’ for the second time. The post-office employees who worked across the street came by to drink their ‘faro’, a sweet, dark beer. The author was unable to afford his attic room and was forced to beg for coal. He commended the locals for their warmth and cordiality. They all knew him by name: the woman across the street who owned a greengrocer’s, the laundryman, the hotel manager’s daughter, a street kid and the family of his ‘friend’ Deprez, the butcher. He frequented the cabarets and night clubs in the area and walked through the illuminated, covered Royal Galleries of Saint Hubert – the very first in Europe –, which he admired tremendously. He knew every tavern and passageway. In this setting of ordinary, wriggling people and buildings, of noise and oh la la, of Brussels, back then still – or already – ‘a bustling city’, a masterpiece was born.

Eduard Douwes Dekker (Multatuli)

Eduard Douwes Dekker (Multatuli)Of course, he is able to put it better himself: ‘In winter of 1859 (…) when I, partly in a room without fire, partly sat at a rickety and filthy little pub table in Brussels, surrounded by good-natured, yet fairly un-aesthetic faro drinkers, was writing my Havelaar, I believed I would be able to bring about something, to accomplish something, to achieve something. That hope gave me courage, that courage made me sporadically eloquent.’

On 19 August 1867, the author addressed the liberal Ghent Van Crombrugghe Society concerning ‘The right to reject a feeling’. He had never been fond of the subject the Society had proposed. In fact, Multatuli believed speeches were useless, let alone imposed themes. Eight years prior to that speech in Ghent, he had written his Max Havelaar. Although it was not easy to get a hold of this book in Belgium, Multatuli managed to amass a small flock of avid admirers in Flanders as well. The author, forever strapped for cash, discovered a market for his lectures. Out there, he hoped to earn a ‘modest steady income’ and even dreamed of playing a part in the Flemish Movement. Maybe, or so he hoped, he had found a new fatherland.

Inspiring orator

That night in Ghent, Multatuli proved to be an inspiring orator who managed to coax a thunderous applause from the enormous crowds, many of whom were labourers. The gathering was marred by the presence of Utrecht professor George Willem Vreede (who had come to Ghent for the 9th Low German Literary Conference), who had returned, in a state of tipsiness, from a dinner with the governor of East-Flanders. Although he had not attended the speech, he erroneously assumed that the author had once again fouled his own nest: ‘Based upon the audience’s enthusiasm, Vreede concluded that the Lebak savage had yet again besmirched Holland and the Dutchmen living in Java’, stated Willem Frederik Hermans in De raadselachtige Multatuli (1976). He continues: ‘He walked up to the front of the room and declared: “I am an honest Dutchman and I refuse to keep quiet here; I want to speak in defence of my fatherland’s honour.” The Flemish people could not make head or tail of this outburst and got ready to lynch him. An outrageous racket ensued, women fainted.’ All of this accompanied by loud renditions of the anthem De Vlaamse Leeuw.

In 1867 Multatuli addressed the Van Crombrugghe Society in Ghent

In 1867 Multatuli addressed the Van Crombrugghe Society in GhentNaive, upright outcasts

That was Multatuli’s moment of glory in Flanders. His financial expectations, however, were never realised. And even though the Van Crombrugghe board, which had made Multatuli an honorary member of the Society after his Ghent appearance, would later organise a fund-raising when he had once again found himself in financial trouble, in his mind, Multatuli kissed the Flemish cause, about which he alternately blew hot and cold, goodbye: ‘hat Flemish movement! That is important, I can assure you. (…) this is just between us: the state of Belgium is condemned. I do not consider what was created in 31 to be viable.’ (In a letter to Busken Huet).

However, just a few weeks later he told the very same Huet this: ‘I have told the Flemish people they will not be getting help from Holland. Misery is expected in that entire matter. (…) They are stubborn, or single-minded, and believe they can convert the Dutchmen to… yes, to what? Naive is what they are, those upright outcasts.’ That is what we, Flemish people, have to make do with: naive, upright outcasts. This label was well-intended, with a note of pity. However, as these are Multatuli’s words, I will gladly take it.